So, did reading Before Watchmen change my experience of Watchmen on the most recent read-through? Surprisingly — to me, at least — yes, and for the better, although potentially not in the way that anyone intended with the prequels had intended. (And, no, not in the sense of, “After reading some shitty comics, Watchmen shone even brighter,” either, to those pre-writing the snark in their heads.)

While some of Before Watchmen (Silk Spectre, definitely, and elements of Minutemen and Nite Owl) gave me an emotional “in” to characters who had, until that point, remained little more than cyphers to me, the more interesting contribution was that submerging myself in Before Watchmen had, somehow, stripped Watchmen of the scary prestige that surrounded it in my head; the idea that it is an Important Work Of Art That Should Always Be Approached And Discussed With Respect disappeared after it had been brutalized by 30-odd comics that sought to pay tribute and cash-in in equal respects, and what was left was… a 12-issue series that isn’t what I thought it was.

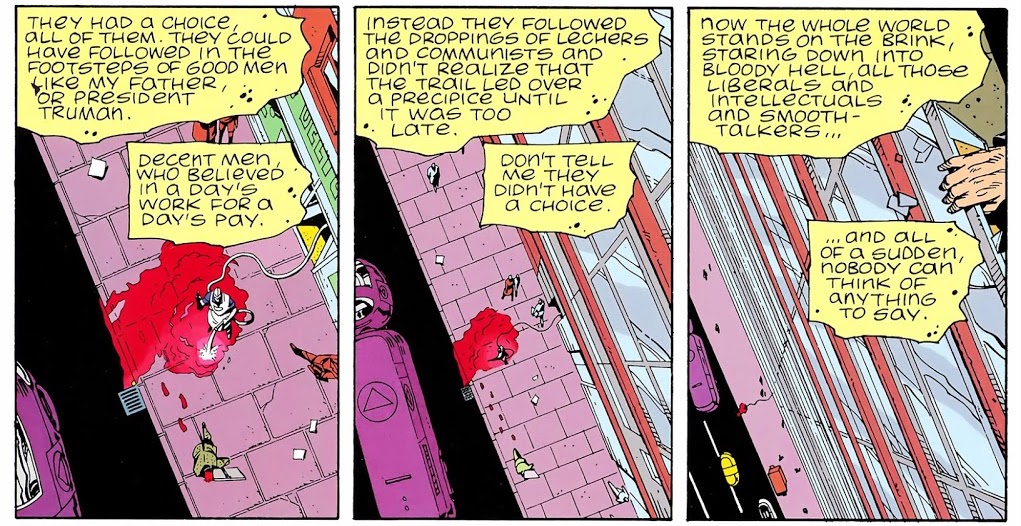

One of the most obvious things that stood out to me in this re-read was how meandering it is, and also how filled with tropes and elements lifted from everywhere; Moore has never been a writer who’s shied away from, shall we say, artfully repurposing his influences, and on this read-through, Watchmen seemed far more of a patchwork than I had previously noticed, with cops talking in crime novel cliches, while Philip K. Dick and Stephen King and Tom Wolfe peek in from the periphery, waiting for their moments on-stage. This isn’t necessarily meant as a criticism, just an observation; Watchmen is much more of a literary League of Extraordinary Gentlemen than I had noticed on earlier reads.

All of that said, Watchmen remains a book that feels curiously devoid of emotion and warmth, for me; perhaps it’s simply that Alan Moore and I vibrate on different frequencies or whatever, but I can see what he intends and where the emotional beats are supposed to land, but every single one of them feels empty. On this read-through, at least, I could appreciate the idea that the Watchmen I was reading and failing to find feeling in was a story being shared by Dr. Manhattan, and therefore of course it’s emotionally empty.

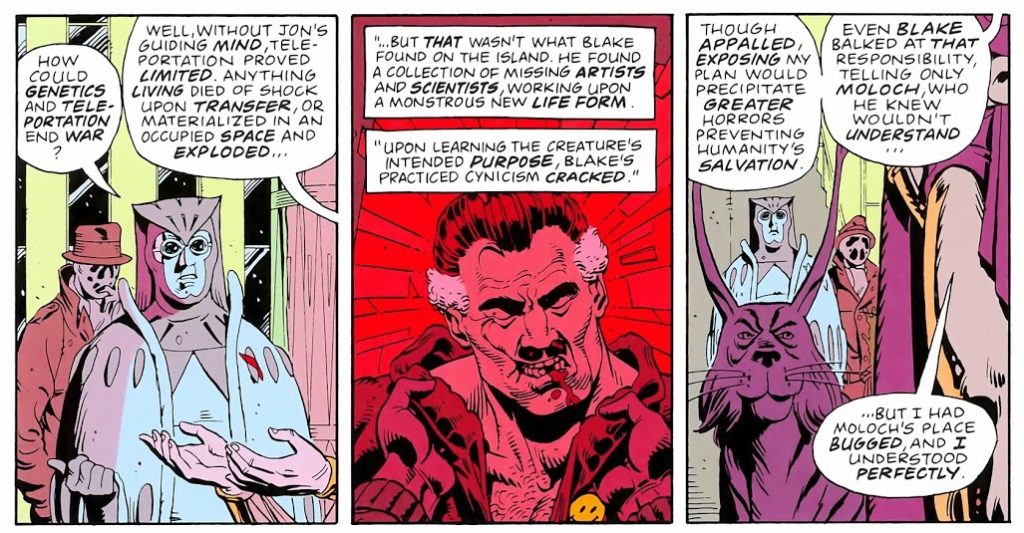

Another discovery: that, for all that the 14-year-old who read this first time out thought that this was “realistic” superheroing, Watchmen is as artificial as the traditional Marvel or DC universe, just in different directions. That only makes sense, of course; it’s limited by the experiences and imaginations of those responsible, and for all their ambitions, Moore and Gibbons were both Brits of a similar age, and that shows in the work. The politics of the book — personal and party political — are simplified to suit the purposes of Moore’s story, and even there, the story shifts and moves direction as Moore and Gibbons get distracted by what they’re doing and start to poke in new places. (Note how utterly unimportant the murder mystery thread of the first issue eventually becomes; there’s a point, around the third issue or so, where Moore and Gibbons see what they’re doing and start showing off, to each other and themselves, with more and more formal play while the plot falls into the background.)

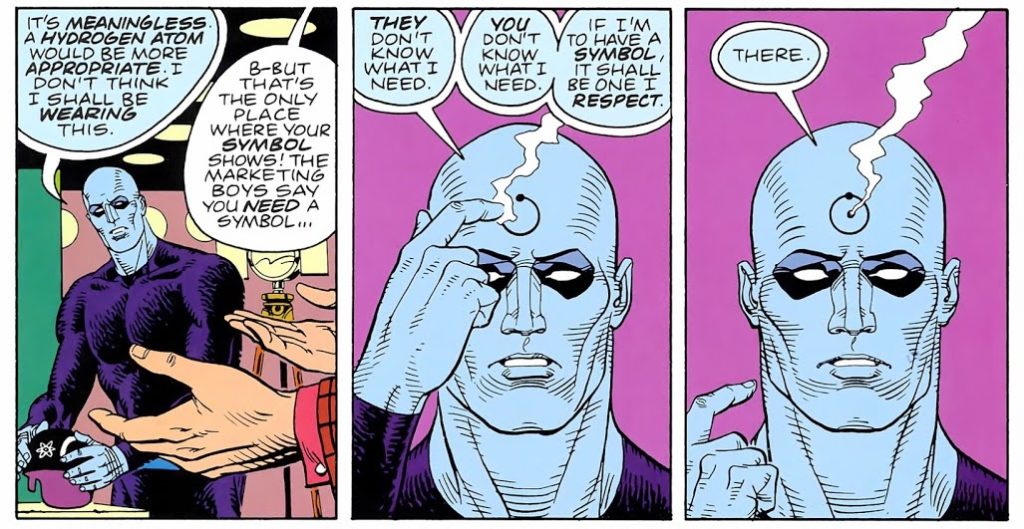

Gibbons emerged as the most valuable player of the series for me on this read-through, his work grounding the book and also giving life to things that, in other artists’ hands, would have lay flat on the page. There’s something to the simplicity of his line, and also the way in which his artwork speaks directly to the genre Watchmen is examining (parodying, critiquing, bemoaning and expanding, as well, maybe); look at the Minutemen in flashback sequences and there’s something about Gibbons’ art that feels like the natural destination of classic Golden Age and Silver Age artists, which gives an urgency and gravity to the contemporary sequences that wouldn’t have been present had, say, Bill Sienkiewicz or Frank Miller had drawn the book. Gibbons’ clean line gifts Watchmen with a legitimacy that appeals to the subconscious, so that the characters read as superheroes visually even as Moore is writing something else entirely.

(That Gibbons can also make some of the more heavy-handed symbolism of the book work on the page as well as he does, and also bring in visual influences alien to American Superhero Comics like Moebius, who feels a particularly heavy note on the way Dr. Manhattan looks, is just more grist to my mill of, “Why don’t more people talk about what Gibbons brought to the book?)

Shorn of the understanding that Watchmen is inherently important and grandiose because it’s Watchmen — a belief borne as much of my own delusions and misunderstandings of the work and its place as a kid as anything else — I rediscovered Watchmen on this read-through as something far messier, imprecise and imperfect than I remembered, or had maybe even noticed before. It made me appreciate the book more, if not necessarily like it much more than before.

Part of the reason for that was the discovery, this time, of a whole new set of concerns. I’ll tell you about those next. (Yes, a cliffhanger! I did it thirty-five minutes ago!* Or something.)

(* This isn’t true at all; because of how crazy the last week has been with comics news, I haven’t done it at all yet. But there’s still time!)

Now you’ve got me remembering the experience of reading it as it came out. My friends and I were in college, and those whose homes weren’t near comics shops were bummed that it’d finish before they got back to campus. Then it took two months to get issue #10 out, and nearly three to get #12 out, so surprise, we all got to be there for the wrap-up anyway. :) I think that in some ways I enjoy it more as a work of parts than the single entity that the collection presents.

Oh, wow. So, I went to do a little research to remind myself what else was coming out at the same time, to give a little development to the thought “Yes, agreed very strongly that Watchmen is emotionally cold and distant.” While we were reading Watchmen, we were also reading: Daredevil Born Again, Concrete, Captain Confederacy (ah, for those innocent days when we had no idea the author would turn out to be a racist troll), Strikeforce Morituri, Batman Year One, the Universo Project storyline in Legion of Super-Heroes, and…drumroll please…Fantastic Four #300! There is no escape, you guys!

Whatever the point I was going to make has gone off and drowned itself in a sea of bemused nostalgia.

Most of that list sounds nicely late 80s, but I can’t get my brain to accept that Concrete started that long ago.

He debuted in Dark Horse Presents #1, in the summer of 1986. I was a bit surprised myself, when I was looking at lists of stuff that happened in comics in a given year.

This was one of the texts in a university course I audited last year. I don’t recall that we spent any time on the book’s plot; the classes on Watchmen were all about form and influences. One of the greatest values of Watchmen as a course material is that after spending several classes explaining to students the various means by which you can tell a story in sequential art, here was a text that was chock full of examples. The dance between word & image in this book is what I most marvel at.

(We also used Moore’s “This Is Information” and Tomorrow Stories’ “How Things Work Out”)