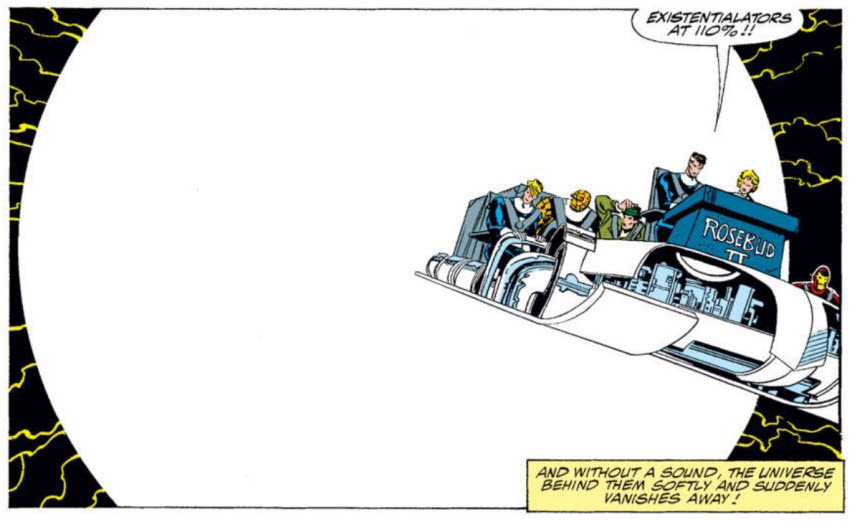

Housekeeping! First, make sure you don’t miss new posts from Jeff (on Red Sonja) and Graeme (on autobio comix) below. Second, also don’t miss Graeme’s similarly-themed (but much better-written!) post over at Wired; he and I only overlap on one run, so you shouldn’t be TOO bored. Now fire up the existentialators and let’s gooooooooooooooo!

So the Fantastic Four cratered at the box office again, a flame-out so spectacular that it makes their widely-mocked last outing (“a juvenile, simplistic picture”) look like The Dark Knight by comparison. This has led to a whole bunch of thinkpiecing and podcast chatter wondering what this means for superhero movies in general and what it says about the Fantastic Four specifically.

Should the movies have followed the comics more closely? Less closely? Is a body horror take appropriate for the property? Maybe it should be all high-gloss pop? But wasn’t that what the last ones were? Maybe it’s impossible to make a good Fantastic Four movie AT ALL! And so on.

Full disclosure: I haven’t actually seen the current movie. But I have found myself compulsively reading (and listening to) these dissections of the aftermath, and — in true internet pundit fashion — have decided that I totally have the answers despite only having a third-hand approximation of the problem. And my basic answer is this: they started off with the wrong comics.

For all that this isn’t adapted from any particular set of Fantastic Four comics, it seems pretty clear that they’re using the Ultimate Fantastic Four as their starting point: younger lead characters; childhood friendship between Reed and Ben; working together at an institute; Doom being their peer; the Storm’s father being involved; etc. And those comics, for all the palpable talent lined up behind them (Bendis! Millar! Ellis! One of those Kubert people!), were not particularly memorable. It was the first major-character misfire (i.e., not that stupid Ron Zimmerman book) in the Ultimate line, and no amount of flailing ever seemed to cause it to make a dent in the gestalt psyche of comic fandom.

Which makes it a questionable foundation on which to build the edifice of a movie that had plenty of other potential problems as well. You understand the impulse — who wants to watch OLD PEOPLE in a superhero movie, amirite?!? and superhero teams with silly names????!? — but it’s the same impulse that missed the mark in the Ultimate comics.

But Fantastic Four is a comic that’s been published for something like 54 mostly-uninterrupted years. Surely somewhere in that vast catalog of lunacy there are some ideas that might better inform a film? (Or a Netflix series? Or whatever Oculus Rift thing we’re doing by the time someone feels brave enough to try again with these characters?)

Yes. Yes, there are. Since binging on the movie’s autopsy reports, I’ve spent some time thinking about my favorite Fantastic Four stories, and trying to figure out what elements made them work for me — I’m an intermittent reader of the book — and how they might translate to the screen. So here, in the spirit of this poor, beleaguered piece of comic book IP and fine internet listicles everywhere, a countdown of four fantastic comic book Fantastic Four eras that might have something to offer the big-screen FF.

4) Fantastic Four #304-332, by Steve Englehart/John Harkness, with Keith Pollard, John Buscema, Joe Sinnott, and a bunch of other people

It might seem bizarre to suggest that the movie FF take its cues from this run, which was so snakebit and harried by Marvel editorial that Englehart wound up switching to his John Harkness pseudonym, basically his own personal Alan Smithee. But there’s a reason that this was the first extended run of Fantastic Four that I ever bought: it’s because the solution to the Fantastic Four being old isn’t to make them young — it’s to actually let the group evolve.

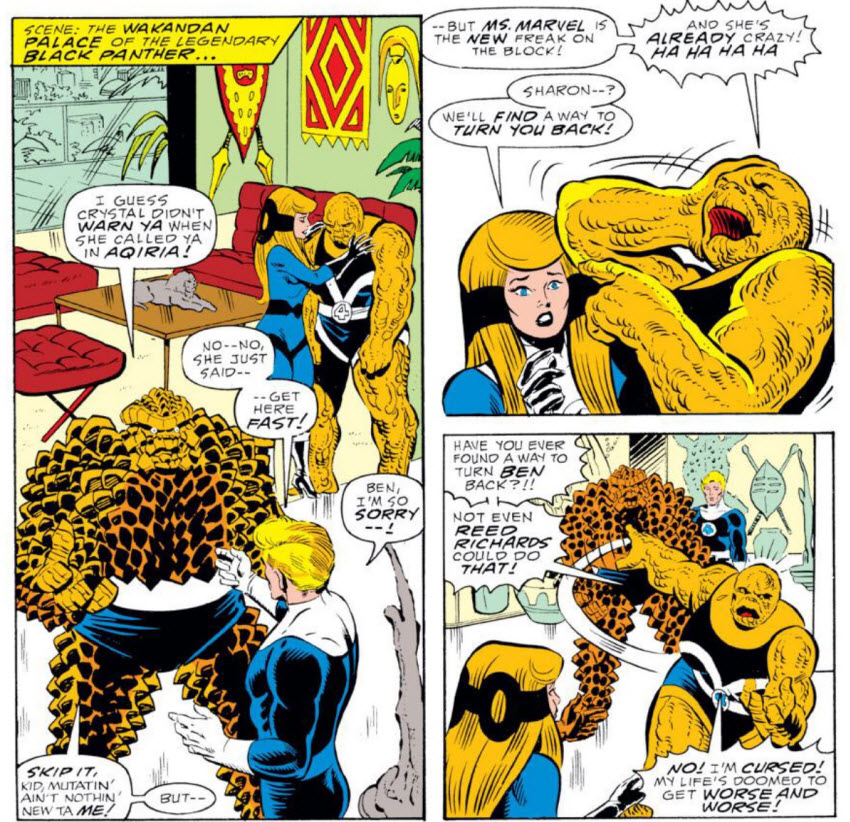

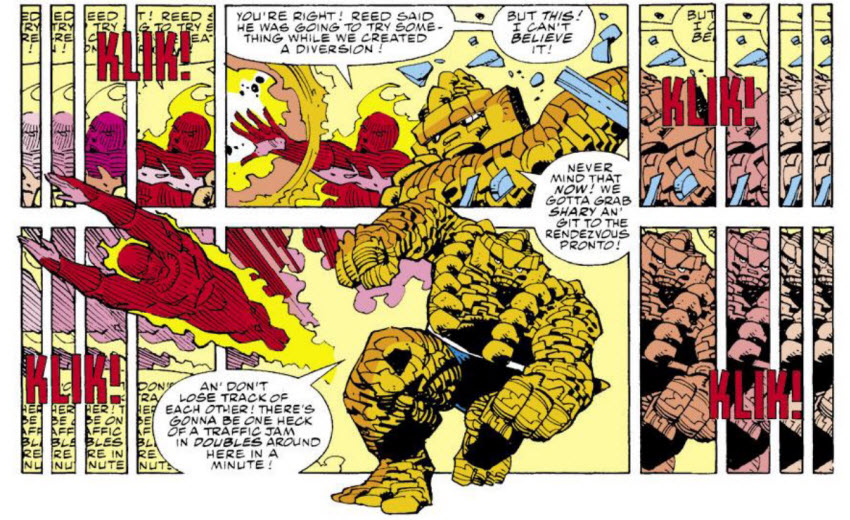

This run, at least before it gets totally gutted halfway through, centers on Reed and Sue leaving the team, with their spots being filled by Crystal and Ms. Marvel (who would promptly be turned into a female Thing), moving Ben and Johnny into then-unfamiliar leadership roles (and further mutating Ben in the same incident that Thing-ified Ms. Marvel). (This was the house ad that got me to buy the book, for example.) It was a book about change, and growth, and mutation. And, like most Englehart books (and most Marvel books at the time, in the first blush of the X-Men-ification of the entire Marvel line), it was about insane levels of melodrama.

(It was also very much a body horror, at least for a time — the panels above are pretty much nothing but melodrama and body horror.)

It’s a run that reads very strangely now, and not only because of Englehart’s frustrations and Marvel’s meddling. (There’s a storyline mid-run that covers many of the same beats as Jonathan Hickman’s current Secret Wars project — Molecule Man! Doom! The Beyonder and some other omnipotent beings! Semi-comprehensible quasi-deep monologues! — only smashed into a couple of issues, and that’s tonally completely divorced from everything else that was going on.)

But it’s a Fantastic Four series that brought in new readers (I can testify to at least one!) and showed very clearly how to evolve the Fantastic Four without losing everything that makes the book the Fantastic Four. Matt Fraction’s FF series followed a similar path; it always felt slightly more divorced from the base concept to me, but you could certainly slot that one into this space and make the same point.

If you’re interested in a more in-depth take on this, there’s a four-part recap of the run starting here.

What to take? A willingness to swap out the original Fantastic Four. An appreciation for melodrama.

What to leave behind? The editorial meddling. The Beyonder, Kubik, and the Shaper of Worlds, and their ten trillion words of exposition. The anachronistic Arab-sheikh stereotype villain Fasaud.

3) Marvel Knights 4 #1-7, by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa and Steve McNiven

I think one of the problems with putting the Fantastic Four in movies is that the people making the movies seem to think the four are superheroes. It’s an understandable mistake, as they have superpowers, dress in costumes, and fight bad guys … but it’s a mistake nonetheless. It’s tough to find mid-film action setpieces for the FF, because their setup rarely lends itself to, say, fighting muggers, or going on patrol — the sorts of mild digressions you can drop into the middle of a movie to showcase the special effects budget.

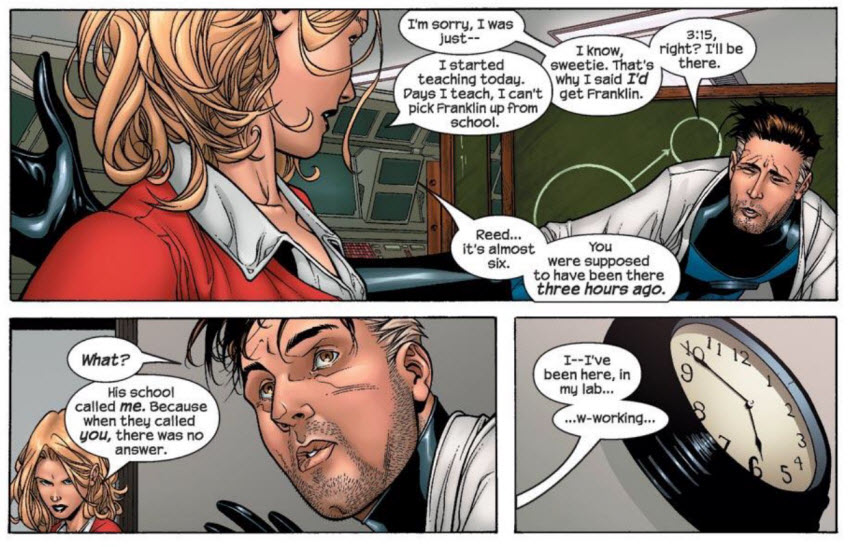

This weird little run of comics took a very different approach, recasting the FF as a family sitcom/dramedy where the leads just happened to have superpowers. The conceit was that the team went bankrupt and lost their headquarters and all their fancy tech, and then had to make their way in the real world, to varying degrees of success and amusing failure.

It’s a book that gets by on brio as much as anything else — Aguirre-Sacasa was still very new to comics at this point, and you can feel the energy of him learning on the fly — ably aided by some stellar artwork from a just-pre-superstardom Steve McNiven. There are moments where the book really just flat-out doesn’t work … but there are also moments where classic FF tropes get a totally new spin, as when Reed pulls his classic “absorbed in the lab” routine and forgets that he’s now a stay-at-home-dad with responsibilities.

I wouldn’t advocate adapting the story directly, but the conceit is a good one, and would make for a Fantastic Four movie that felt completely distinct from the X-Men and Avengers films (although maybe not from The Incredibles, which was released the same year as these stories).

(One sentiment that underlies both of these first two entries is the idea that we could have a Fantastic Four movie that presupposes the existence and career of the original FF without having to see the goddamned origin again. This is a property that, in addition to umpty-thousand comics, has managed to generate four separate animated series across four separate decades, along with three released feature films, one legendary unreleased feature film, and countless toy tie-ins, Slurpee cups, etc. I really think we can safely assume people know the basic story by now.)

What to take? The concept of focusing on the Fantastic Four as normal people in a normal world while de-emphasizing the fighting and supervillains and all that.

What to leave behind? The rough spots. The editorial heavy-handedness that undercut this book before it even launched (it was originally slated to replace Mark Waid’s popular, enjoyable run). Johnny’s ill-fated fixation on Keanu Reeves.

2) Fantastic Four #542-553, by Dwayne McDuffie Paul Pelletier

I’ve got this pet theory that interstitial runs almost always make for deceptively good comics. That is, if you’re coming off one run by a big-name creator, and you’ve got a gap before another big-name creator comes on board, whoever it is that gets slotted with the thankless task of filling that gap will turn out work that is solid at worst, and often better than the big-name runs on either side of it.

There are plenty of examples of this — Chris Roberson’s solid post-J. Michael Straczynski, pre-New 52 work on Superman; Kieron Gillen’s post-JMS, pre-Matt Fraction work on Thor (which was so well-received that it went on to spawn its own iconic run) — but this McDuffie run on FF will always be the best for me. Like Roberson and Gillen, he’s following JMS, and he’s theoretically preceding Mark Millar (although Millar’s run was also beset by all kinds of disruptions), and he just takes the opportunity and goes to town with it.

Like in the Englehart work, this plays with the idea of who can be in the FF, but this time we tie the concept more firmly into the wide Marvel Universe, as Storm and Black Panther (married at this point, making them appropriate Reed/Sue surrogates) join up. In fact, one of the defining elements of the book is how joyously it plays with the entirety of the Marvel Universe, from the weird cosmic beings all the way down to Gravity, hero of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. It’s a breezy, fun read, and a delightful way to spend 12 issues or so with these characters.

What to take? The FF as established in a wider, weird world. The idea that the FF can incorporate other heroes. The brisk, funny, smart tone of the book as a whole. (In a much better, happier world, the late McDuffie’s own TV experience, combined with this run, would’ve made a strong argument for making him the showrunner on a hypothetical Netflix FF series. We live in our own dark future.)

What to leave behind? Gravity. The late storyline featuring people travelling back in time from a dark future. I am so, so tired of dark futures.

1) Fantastic Four #337-354, by Walt Simonson

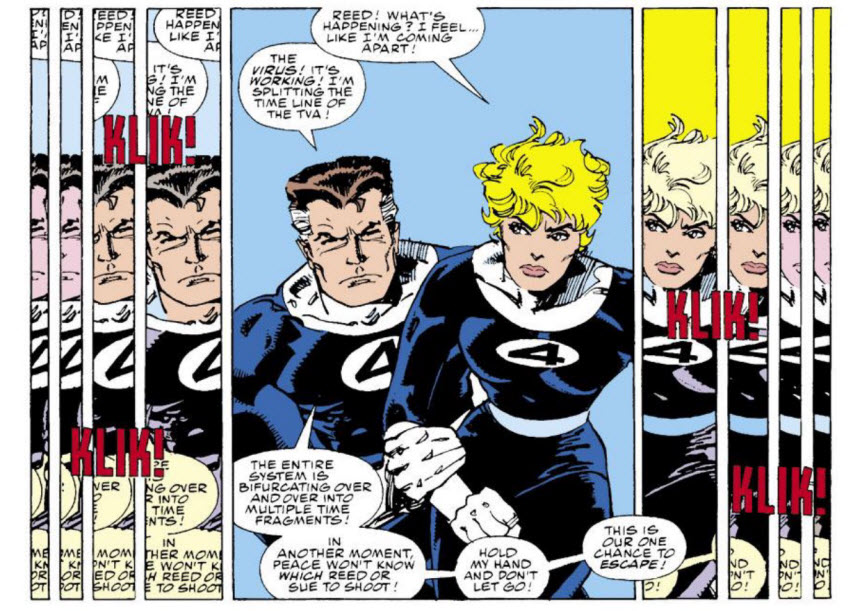

With all apologies to the main two contributors to this site and their Herculean ongoing analysis of what’s generally considered to be the iconic FF, this is my definitive Fantastic Four run, and nothing else comes even close. Simonson is one of my favorite writer/artists on superhero books. Issue #352 in this run, in which Reed has a non-linear fight through timestream with Dr. Doom through one track of the comic while the rest of the characters make their linear way out of Doom’s traps in the other, is a strong contender for my favorite single-issue superhero story of all time. I’m kind of a mark for this, is what I’m saying.

But I think the potential cross-media appeal goes beyond my personal fondness. Something like 70,000 words ago I mentioned that the failure of the movie had led to much navel-gazing about if the FF is a superhero team, or a family story, or a science explorer story; I’ve also suggested above that it should be a comedy, a melodrama, or a large-scale Marvel crossover. Simonson’s run is every single one of those things and more.

In just 13 issues (#347-349 are a bizarre, Art Adams-drawn gimmick starring the Ghost Rider, Wolverine, the Hulk, and Spider-Man; #342 and #351 are fill-ins), Simonson manages to squeeze in fun extrapolations off the Kirby/Lee concepts (the radical cube becomes a radical dodecahedron! someone finally uses the ultimate nullifier!), some Steranko-esque pop-art effects, a Judge Dredd pastiche, a wholesale retconning of Dr. Doom that is subsequently completely (and unjustly!) ignored, an extended fight between the U.S. military and some dinosaurs, the resolution to plots begun in his aborted Avengers run, appearances by Thor and Iron Man, a fight with Kang, the truth of the Dreaming Celestial, the death of Galactus, and, oh by the way, legitimately likeable and engaging versions of Reed, Sue, Johnny, and Ben.

And it’s all done in Simonson’s slashing, kinetic art style, totally removed from the book’s usual reliance on the more staid line of a Joe Sinnott or John Byrne.

This is the Fantastic Four I want to see in a movie: a group at the peak of their powers, exploring because they can, righting wrongs when they have to, palling around with Thor and Iron Man, just generally doing cool stuff and really seeming to enjoy it. It’s not iconic like Simonson’s Thor run, and it hasn’t stuck with the characters for years like Byrne’s run, but if we’re talking about an approach to the property to be detached and used in other media, this is without question the way I’d like to see it go.

(One telling note from these last two suggestions is that the Fantastic Four as a group is much better when they’ve got the rest of the Marvel universe around them. It allows them to establish their own niche in the hierarachy of a superhero-centric world, which, in turn, helps them not just be generic Dudes In Tights Fightin’ Crime. Like every other amateur pop-culture writer on the internet, I have at least a vague understanding of the rights situation that keeps the FF separate from the Marvel cinematic universe; I’m just noting that it would be to everyone’s tremendous benefit to get that squared away ASAP if people actually want to have successful FF movies. The X-Men metanarrative can — and arguably should — stand apart from the Marvel universe and still thrive. The FF … less so.)

What to take? Everything. Go full Zack Snyder shot-for-shot and replicate all 13 issues. (Seriously, though, don’t this. It is always terrible. But take the core ideas, attitudes, and storylines.)

What not to take? The bit with Ghost Rider and Wolverine and the Hulk. It wasn’t funny the first time around.

I am eternally heartened to find so many people coming out and saying that Englehart run was a favourite. It was the first time I really followed the book and inculcated a love in me of the times when FF would run in wacky configurations for a bit. Even at the time I could see it was built on quicksand, but I enjoyed it.

Plus Stegosaurus Thing was some nifty design.

But the Simonson run was some quality stuff. I’d love to see a crazy high-concept movie wherein they adapted the issue that has Reed and Doom fighting at irregular moments in time, but I dunno how you’d do it cinematically, as it both sidelines the other 3 members and probably would be like watching Memento on PCP.

Yeah, I feel like trying to adapt issue #352 would run you smack into the Watchmen problem — so much of what makes it clever has to do with how it understands the medium of comics that the only way to truly adapt it is have it approach film the same way.

The obvious example is the bit where the cover is actually an essential, integral moment in the story that’s never otherwise fully explained if you’re not paying attention. Tough to replicate in a movie. (But WHAT IF you put that moment on the poster to the movie/the DVD case/the OnDemand icon, including the timestamp, and treated it the same way?!?!?!?! And what if you told the movie in linear time but had Reed and Doom popping in and out in their out-of-sequence sequence, and offered the OnDemand/DVD option of watching their fight in order?!?!?!!? AND AND AND)

God, I love that run of comics.

very happy to see this, Matt! Simonson’s FF run is my favorite ever, and it seems to be a blind spot for both Graeme and Jeff. Looking forward to them having their faces melted off by it when they finally get to his run on the Baxter Building podcasts