If you’ve been listening to recent podcast episodes, you’ve heard me talk about reading Sun-Ken Rock by Boichi in a number of ways: furtively, reluctantly, or else in full-on babbling confessional mode. I think the last time I mentioned the strip, I was talking about turning to pirate manga sites to fill in the twenty section gap in the middle of the Crunchyroll manga library.

Here is a comic I am willing to steal for, and yet I’m extremely reluctant to write about it. Extremely reluctant. I am a guy what likes talking about Batman, for crying out loud, or pining for the days when Skull The Slayer was an ongoing title. My sense of shame is pretty underdeveloped, at least when it comes to talking about the popular cultures.

But when I think about writing about Sun-Ken Rock, I don’t see it turning out well for me. I think it’s worth trying and maybe untangling some of the knots in my thoughts about it. My worry is I’m going to come off like one of those dudes trying to justify what is clearly an unhealthy drug addiction: “Oh sure, other people have trouble with meth, but my complexion looks great!” But, hey, if that’s how it’s gotta be…

(More behind the jump, because I’m probably going to put a *ton* of images in the post.)

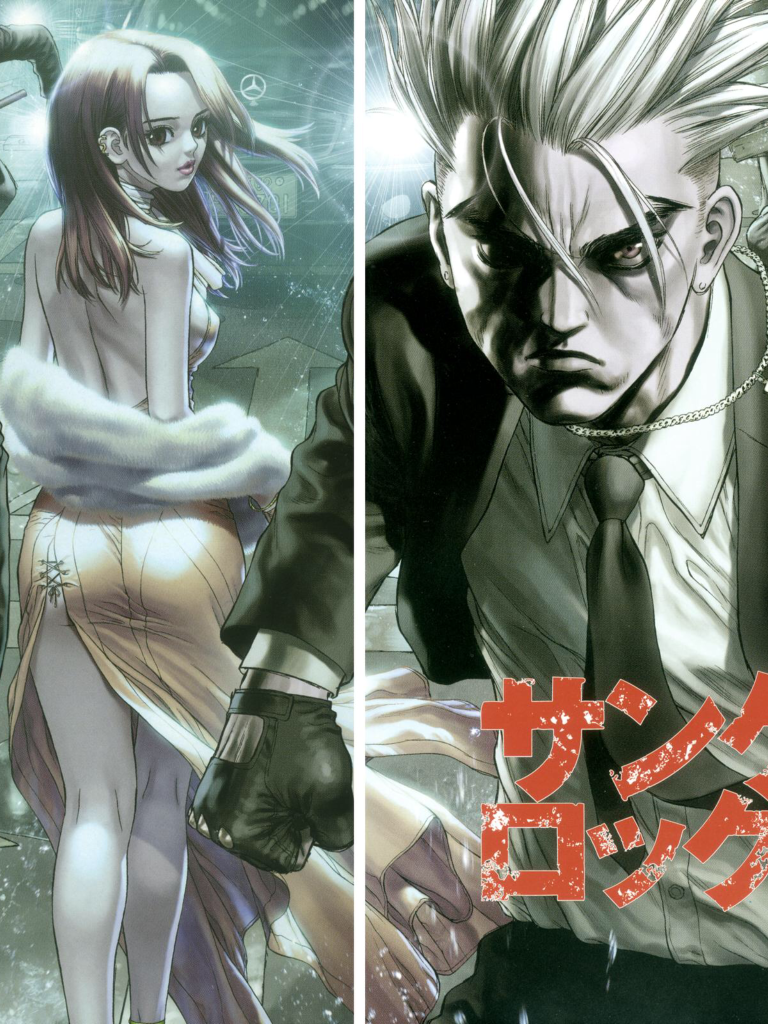

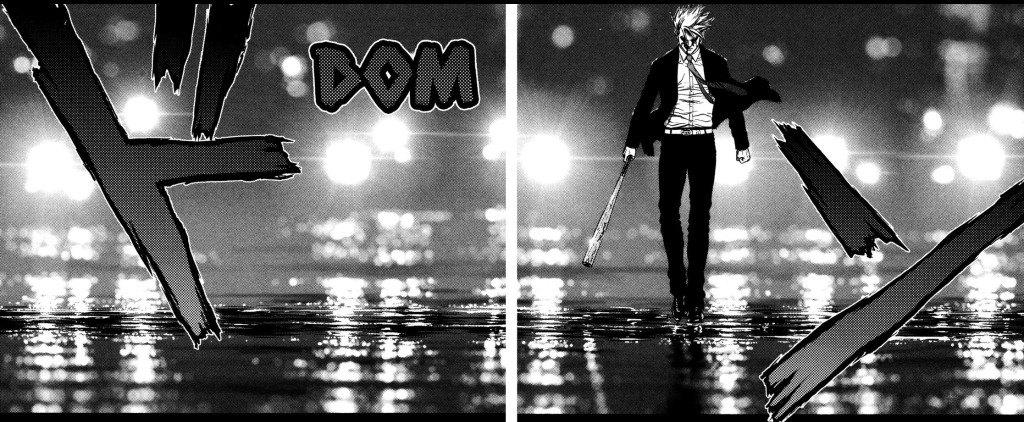

Since 2006, SKR’s been running in the biweekly magazine, Young King, a seinen magazine, which means it’s aimed at older male teens and young adult men. And although Boichi is no spring chicken (he’s 42 now, and was 33 when the series started), part of what makes the series work is how well his tastes align with his target audience. It’s not just that the series is packed with fights and expensive cars and high fashion and women in alarming amounts of undress, it’s that Boichi and his team make all of those things bigger than big. Sun-Ken Rock is the kind of series where Ken will do a mid-air flip above their enemy in a double-page spread, and the artistic team will lavishly detail the sole of his expensive shoe, the Armani logo prominent in the center of the panel. If you want to read a manga that makes a Michael Bay movie look like Last Year at Marienbad in comparison, Sun-Ken Rock is the book for you.

It starts off all over the map, a story about a young Japanese wastrel in love with Yumin, the top student in his class, but he finds out at graduation she’s returning to Korea, her home country, to become a policewoman. Crazy in love, he follows but with a lack of skills or education, it’s only time before he ends up in a Korean gang.

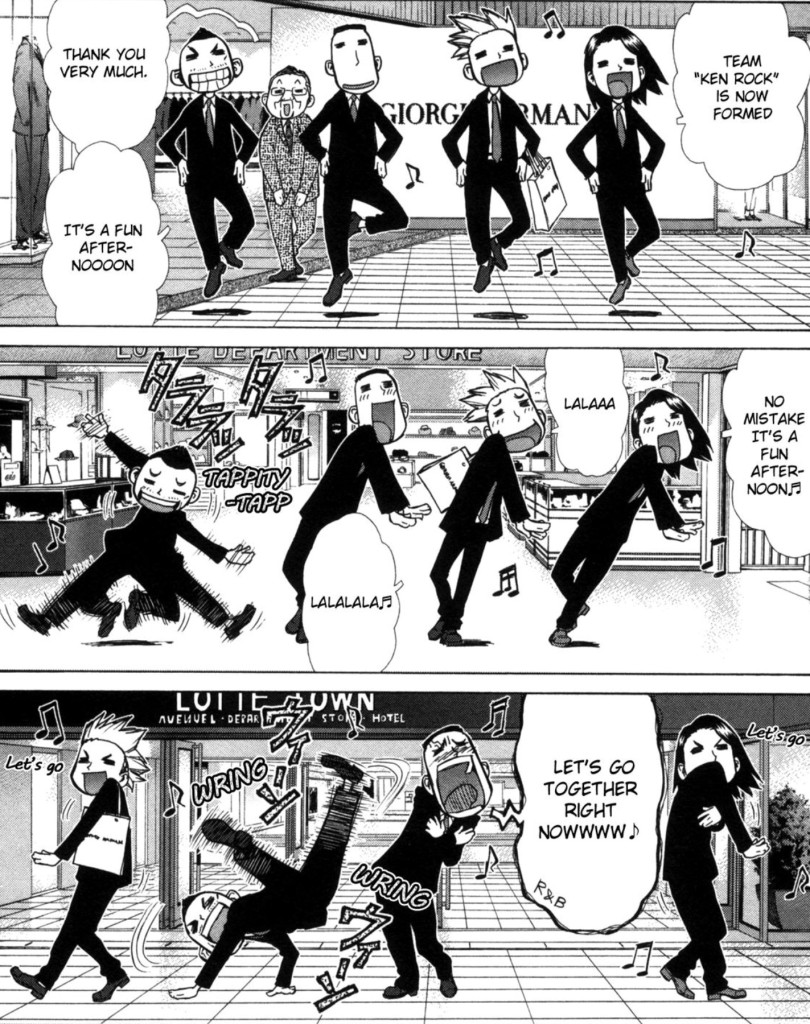

It sounds like romantic comedy manga 101, a quarter-step away from something like Nisekoi, but it doesn’t stop there. Of course, Ken doesn’t want to belong to a gang and commit crimes—he only wants to make something of himself, find his place in the world, while continuing to protect the innocent from bullies—so the down-on-their-luck gang can only recruit him by making him the boss, paying him a decent salary, and pledging to help him defeat other local gangs so that helpless vendors and shopowners will be safe. It’s a view of organized crime that makes One Piece‘s upbeat approach to maritime piracy look gritty, and, like One Piece, it gives us a reason for lots of fights, as Ken goes about gaining powerful recruits by punching them into a fine paste and impressing them with his moral rightneousess.

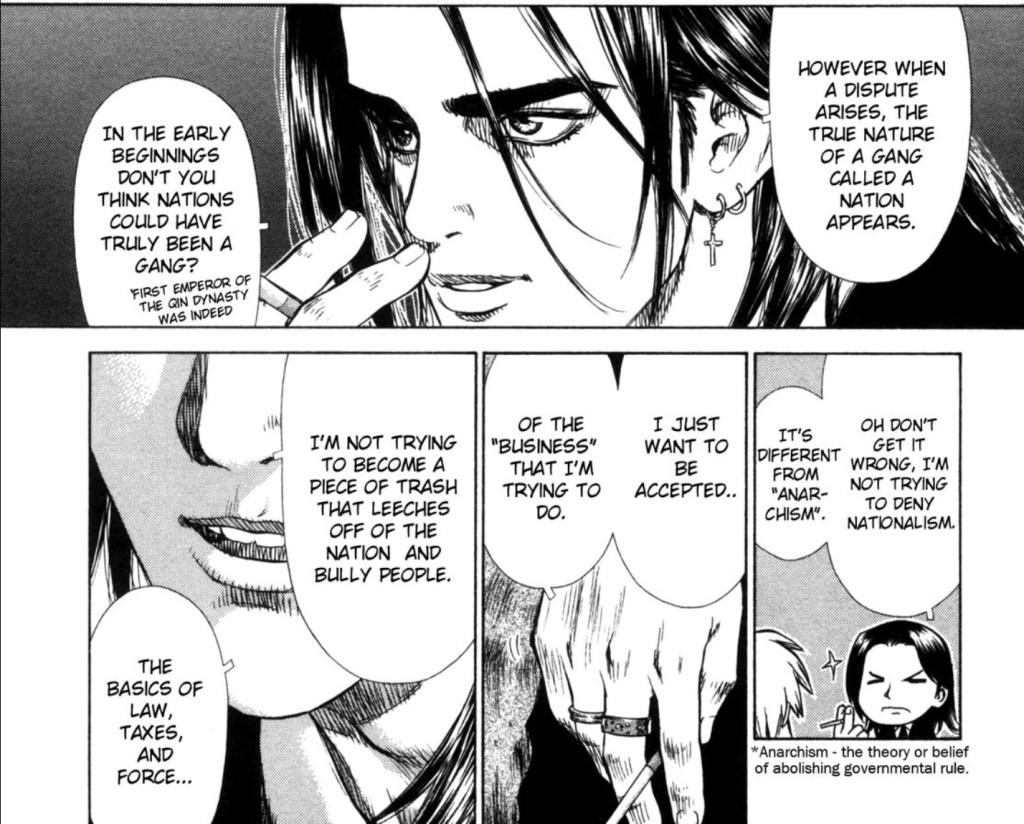

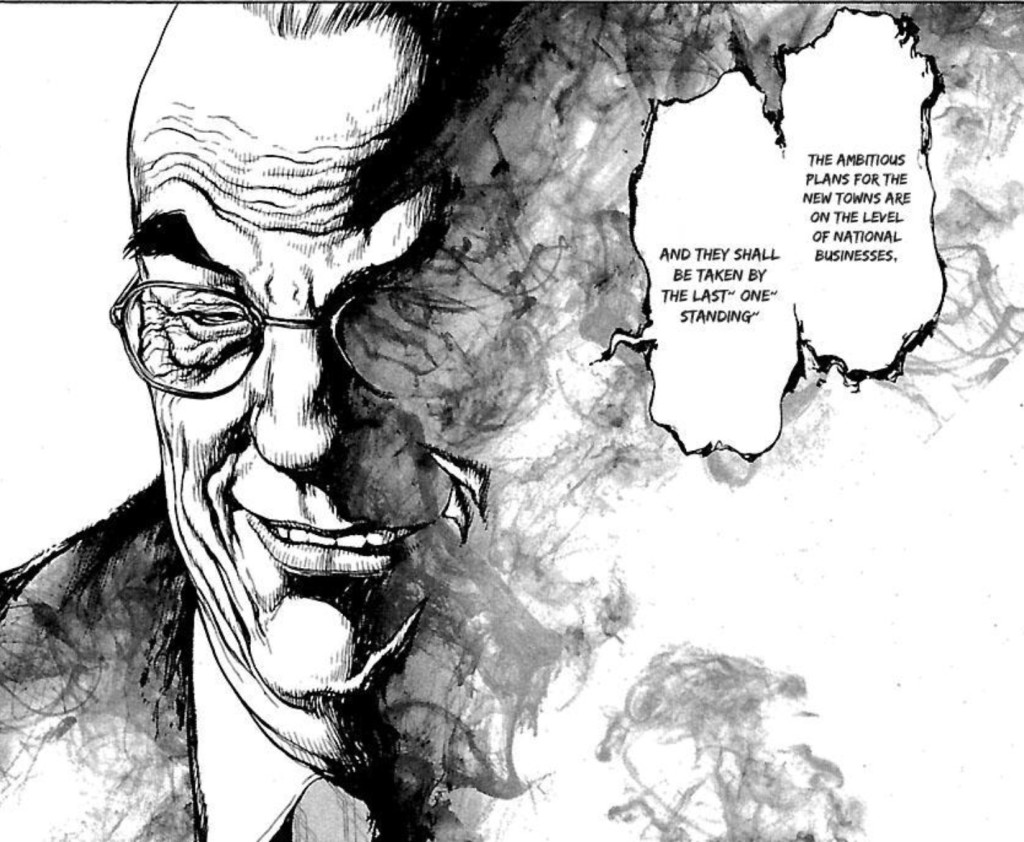

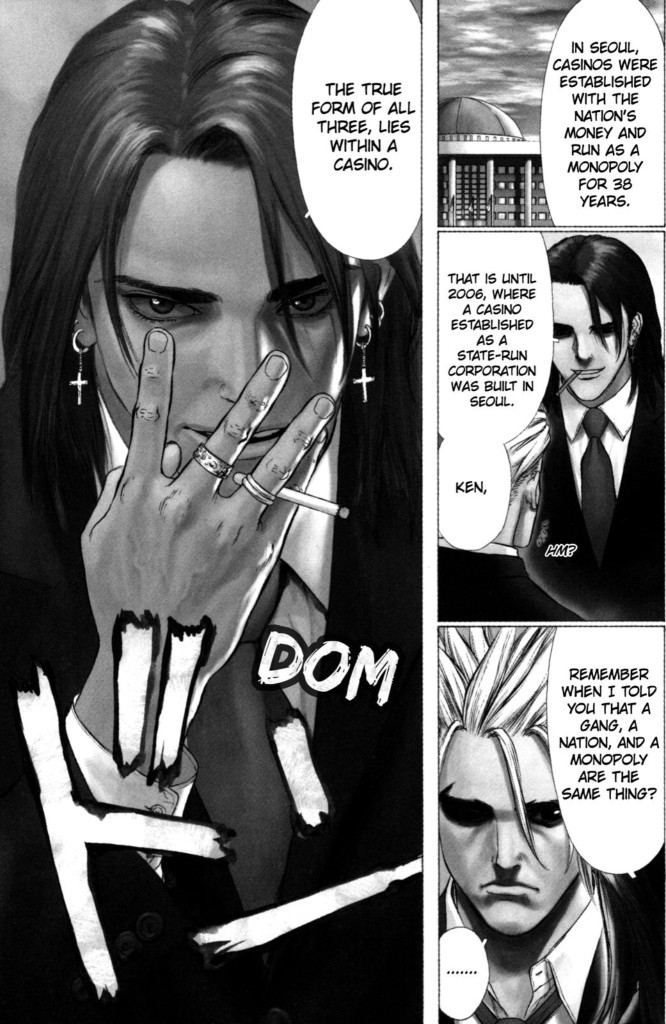

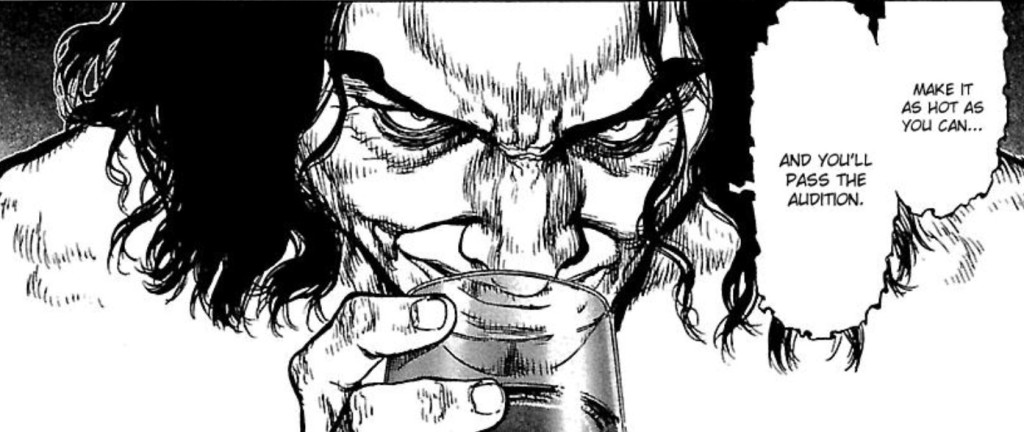

So it’s romantic comedy manga 101 plus a shonen jump series with swears? Yes, but—to quote the TV ads of my youth—that’s not all! The man who recruits Ken is Tae-Soo Park, a charismatic Korean mastermind obsessed with forming the most powerful gang in the country. Throughout the series, Park talks about nations being gangs, taxes being extortion, laws being only the rules of conduct the head of a gang dictates to those who serve him, rules that don’t necessarily apply to the leaders if they decide not to follow them. Park is Ken’s right hand man because he chose to follow Ken, but many of the missions the Sun-Ken Rock gang undertake are at his suggestion, and the series is awash in suggestions that Park is playing a more sinister long game than anyone knows.

Boichi had originally intended SKR to be a “dark manga,” something like Death Note, before the editor nixed it and demanded something funnier, but the series regularly dips in and out of nihilism. I’m at least two volumes from being caught up, but part of Park’s master plan has already been revealed as pumping so much money into the overinflated Korean real estate market that the collapse is catastrophic, which will allow him to rebuild the government in a way more amicable to all. And I’m not even touching on how Boichi, a South Korean manhwa turned Japanese mangaka, has stories turn on Korea’s role in the Vietnam War and its less than stellar track record with immigrants, at least in part as a way to critique in a coded way Japan’s similarly corrupt and unjust approaches.

So is this why I’m so reluctant to admit I like Sun-Ken Rock, because it’s a dark romantic comedy manga with strong shonen roots and is therefore clearly as tonally inconsistent as all hell?

In fact, no. Like a certain number of dudes my age, I was into Hong Kong action films back during what I think of as “the heyday:” 1989 through about 1994 or so. And there’s nothing like that era of films to make one a fan of tonal inconsistency: you’d get classical farce, brutal fights, crazy supernatural events, and a dash of romantic melodrama all on one ten minute reel…and it took nine of those reels to make a full movie.

No, just like with Bay, the erraticism of can be a deal-breaker for some but not for me. And just like Bay, Boichi and his crew bring a ton of technical devotion and brio to their story. By now, I’m used to manga cutting between a more realistic style and kawaii or stick figure reaction shots for the comedy, but Boichi and team occasionally cop moves straight out of Sienkiewicz, photo-realistic faces framed with Steadmanesque smears of ink…and not just for the comedic bits, either.

One of the early successes of Sun-Ken Rock is how Boichi plays with the double-page spread in a way that reminds me of Shonen Jump’s One Punch Man—page and a half spreads with an extra panel at the end to change up reaction shots, or punches and kicks that startle being thrown farther than you’d think but also ending sooner than you’d expect: the queasy feeling of surprise and awe you get when suddenly a fight is happening to you or around you.

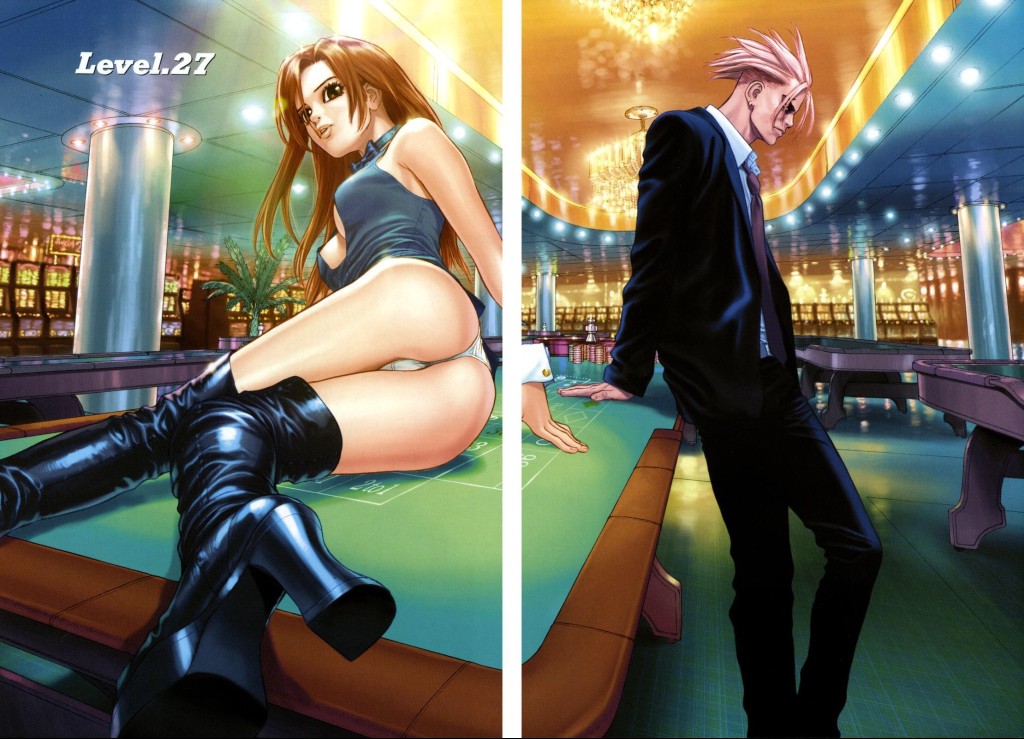

The proficiency becomes the tone, the grounding element, even as the pitch cranks higher and higher. And even then, the SKR arcs have to run hot and cold, four or more low-stakes chapters before the stories start to ramp up again and the gang has to take over an entire casino resort by force or fight an unbeatable group of assassins comprised entirely of embittered foreign immigrants.

In its way, Sun-Ken Rock reminds me a lot of Garth Ennis’ The Boys: it’s juvenile and unsubtle and mostly predictable (and Ken’s brothers-in-arms are similarly wacky, mostly in more generic ways, although the character of Pickaxe would fit in perfectly with Ennis’ idea of comic relief), but it’s also not without something serious to say, it knows its modern history, and its more clear-eyed about corruption and injustice than all the face punching and poop jokes would lead you to expect.

But…

As with Ennis’ The Boys, sexual issues in Sun-Ken Rock are problematic. Very, very problematic. Say what you will about Ennis’ swiping of one of Chasing Amy‘s main plot points, but at least you get the sense Ennis was trying to acknowledge male insecurity about female sexuality, something a bit more fair-minded than all the scenes of hate sex and pedophilia and slobbering orgies we were supposed to find so knee-slapping.

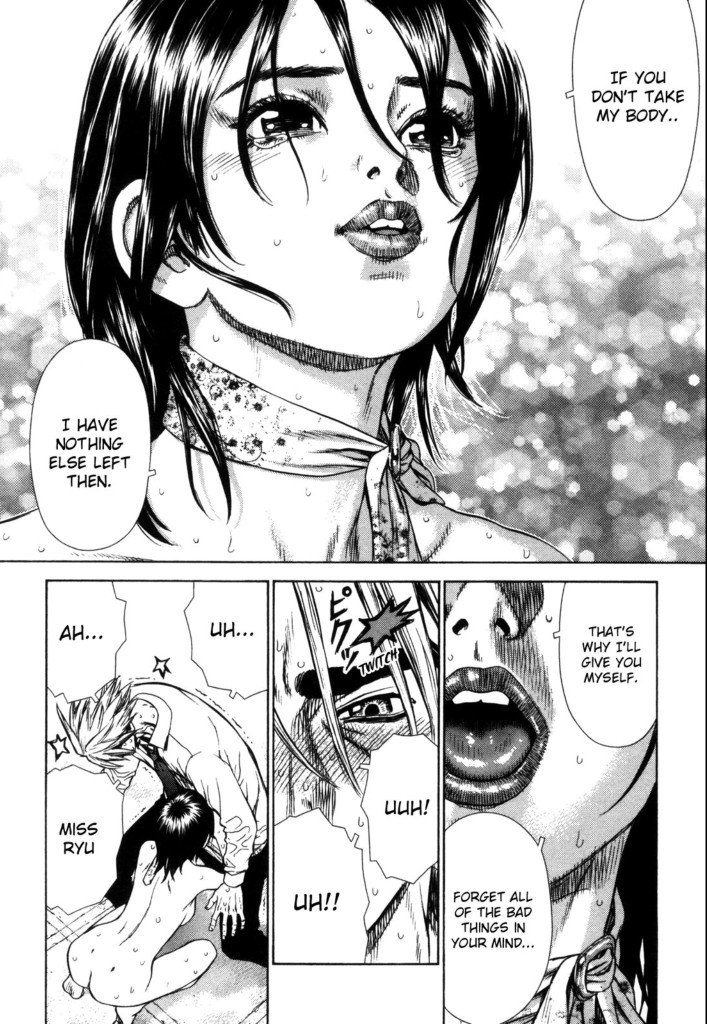

That practically makes The Boys an Erica Jong novel when compared to the sexual politics of Sun-Ken Rock. Because Ken is in love with police officer Yumin, he is chastely devoted to her, virginal. So it makes narrative sense an early chapter of the series would have a Tea House barmaid try to seduce him as a way of repaying him for saving her from a near-rape at the hands of an opposing gang. Disappointingly hackneyed narrative sense to be sure, but I can understand it: you get to show part of what makes the good guy good, and you also get some cheap titillation thrown in there. It’s an exploitation storytelling staple.

However, just as Boichi and crew commit to making their action and comedy scenes as over-the-top as possible, that scene plays out wayyyyyyyy more explicitly than one might expect. And it’s followed half an arc later by the appearance of Kae-Lyn Kim, a weapons specialist who promises to give herself to the member of the Sun-Ken Rock crew who first masters her sashimi knife lessons (it’s a Korean gang thing, the sashimi knives). She’s a modern day porn star equivalent of Red Sonja, except there’s no defiance to her challenge: before he can even be tested, she is cooing and whimpering over Ken, begging him to take her.

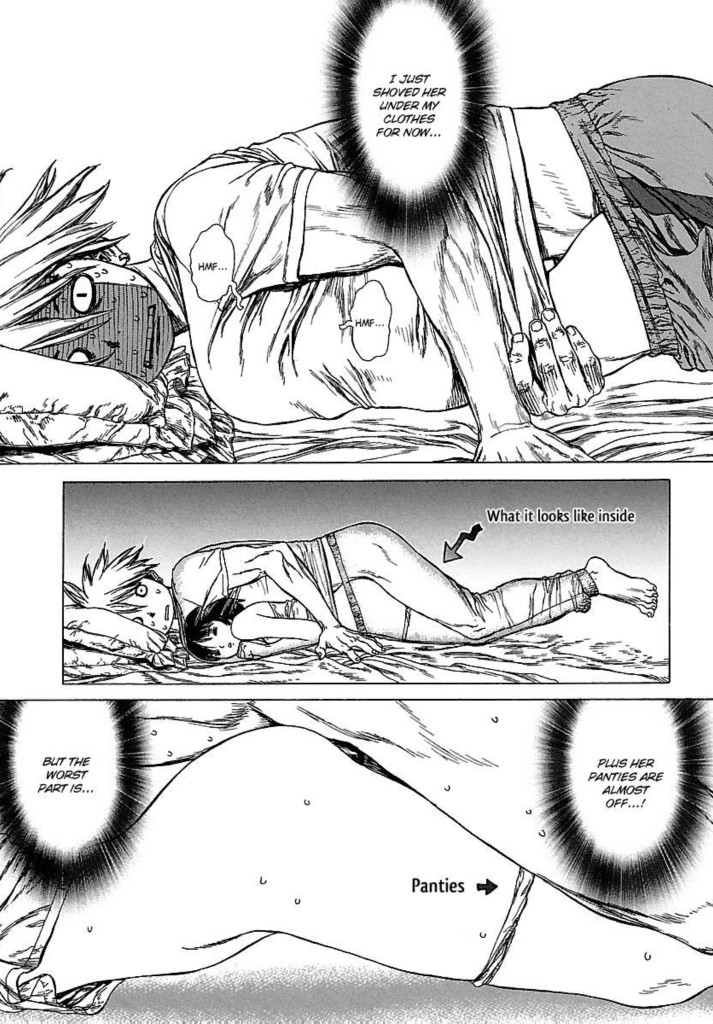

Sun-Ken Rock is the kind of series where the protagonist will get trapped in a service elevator with the Korean pop star he’s been charged with protecting, and somehow end up with his penis partway in her eager vagina entirely by accident, a series where female antagonists use their sexuality to distract and castrate their enemies and are only capable of being conquered by their own lust. Even Yumin, the virtuous policewoman who’s more than what she seems, can’t have a fight that isn’t drawn from a POV tucked just below the perineum. (And, of course, her flashback origin includes a stoic, devoted bodyguard who ends up lustfully ripping the clothes from her fourteen year old body.)

So it’s not just that Sun-Ken Rock is a dark romantic comedy manga with strong shonen roots. It’s a dark romantic comedy manga with strong shonen roots and a surprisingly strong dose of hentai. (I guess it’s not that surprising if you know that Boichi in fact drew about a dozen hentai shorts before he started Sun-Ken Rock, but it’s a pretty big surprise for an ignoramus like me just turning the pages on the Crunchyroll app.) (And also, let me just add that here, as with his other material, Boichi knows his shit: re-looking over a chapter detailing a sexy Korean pop star photo shoot gone awry, I finally realized that, yes, some of the panels are deliberate Guido Crepax tributes.)

As I said, I’m the guy what likes to talk about Batman. And I’m also the guy what published Erotic Vampire Bank Heist. I’m not a prude (said every prude in the history of ever) and I don’t mind porn with a plot, or a plot with some porn.

But whereas Sun-Ken Rock gleefully tears past the limits of nuance in its action, comedy, and melodrama to its advantage, its similar approach to sex works is a disincentive, not least because Boichi and crew have set their story at the street corner of Slavery and Rape. There’s an entire volume devoted to Ken working as an intern in the Korean pop industry, and sexy harem scenes of him shacking up with the five upcoming stars he’s supposed to protect happen right before and after intentionally ugly scenes of producers demanding—and receiving—sexual favors from singers desperate to break into the industry.

It’d be one thing if the reader’s nose was being rubbed in it, a Sadean outrage at hypocrisy being turned against us or something? But at best it’s just SKR’s tonal indifference finally working against it. And at worst? It’s pandering that reveals an ugly mindset: seeing panties, nipples, and pubic hair is exciting and awesome, no matter what context the readers sees them in. It’s all good, even when it clearly isn’t. And perhaps because there are so many scenes where the sex is clearly being played for laughs (as you can imagine, that elevator scene has at most a half-ounce of seriousness to it), it makes a similar sex-obsessed panderer like Kazuo Koike seem like a contender for the Alfred Kinsey Sexual Maturity Award by comparison.

There are some of us who enjoy the freedom granted by comics’ low art status: it’s amazing how much more you can pack into a story once you squeeze out all the tastefulness. But Sun-Ken Rock proves that it’s easier for moral ugliness to slip in when those buffers are removed. At my most optimistic, I think Boichi and his team are people who believe more than a little in Ken’s righteous desire to protect the weak, and their treatment of women is just an (appalling) oversight due to the mores of their culture(s). But I’m old and cynical and so, more often than not, it looks like dudes who don’t care how close their treatment of women is the opposite of protecting the weak. While exploitation genres of all kind have almost always made it a point to leave sexuality on the table, it’d be nice if Sun-Ken Rock hadn’t taken aberrant values and blown them up to 21st Century extremes. From such an oversize vista, it’s easier to see how the hypocrisy leads to exactly the kind of injustice Sun-Ken Rock wants to eschew, making it a guilty pleasure where guilt is a far larger part of the equation than it should.

“Throughout the series, Park talks about nations being gangs, taxes being extortion, laws being only the rules of conduct the head of a gang dictates to those who serve him, rules that don’t necessarily apply to the leaders if they decide not to follow them.”

Sexy libertarianism!

Your description of Sun-Ken Rock makes it sound like every manga ever squeezed into one.

Jeff, never stop talking about your mingled delight and horror at all those Crunchyroll series I haven’t gotten around to reading. I particularly loved your comment about the HK New Wave flicks– I got into manga around the same time as I started watching those, and I think it did kind of acclimate me to the different, more melodramatic and tone-clashy storytelling priorities in East Asian pop culture.

Thanks for writing this piece. I’ve been thinking about this exact topic a lot lately… I’ve more or less quit reading Big Two series and get my pop trash comics fix from manga, but once you stray outside the Shonen Jump battle arena you start hitting culture clash almost immediately. I have one friend in particular asking for seinen recommendations, and pretty much everything I think is interesting has serious potential dealbreakers regarding sexual content and/or graphic violence. It says something that probably the least objectionable series I can think of is Battle Angel Alita, and that only because Kishiro usually doesn’t bother drawing blood all over the exposed brains getting smashed! A Bride’s Story might be my number two, but the May-December thing is likely a serious landmine in its own right.

I think it’s just one of those things you have to get used to if you want to read pretty much any seinen series that isn’t a slice-of-life character study (and sometimes even those), and I don’t begrudge anyone who can’t or doesn’t want to make that adjustment. Hell, I consider myself reasonably desensitized in this regard, and I’m still put off by the sheer cruelty in Berserk or pretty much anything by Kazuo Koike. Mind, it’s not like the stuff aimed at women is free of sex and gender issues by Western standards either, be it the often crazy sexism in shoujo or the overwhelming rapiness of yaoi…

Actually, I should really say “American standards”, because lord knows I’ve seen stuff in Eurocomics that just makes me say noooooope.

I’m reading Sun Ken Rock now and I must say, while the rest of the story is certainly over the top with everything, sex included, and obviously permeated by macho culture, the Idol Arc really is all sorts of bad. I get the impression Boichi really fucked up there, not just sex-wise but in all respects. The entire predicament is idiotic, and removing the well-known and loved cast of the gang reduces awfully the options for the story. It’s basically a different manga, and I get the impression that all the random sex was put in also to fill with shock values the pages orphan of long-standing gags and established characters. And yeah, it gets awkward because of all the rape and near-rape but in a way I found even weirder the consensual-ish stuff (the -ish being because in most cases there it’s actually Ken who almost gets raped, though it’s played for laughs) because it was so in conflict with the rest of the story. These idols are (rightfully) angry at the way their producers try to exploit them sexually… except then they are suddenly all trying to jump their producer’s bones for no reason at all. Tonally the entire thing is a mess, writing-wise the entire thing is a mess, character-wise the entire thing is a mess, and even the final fight, the only half-decent thing to come out of it, still makes no fucking sense because it’s solved with an asspull so ridiculous it might as well have said “and then Ken win because he’s the protagonist” (okay, he always does, but you get my point).

So I suppose if in some future edition of this manga all that part gets simply removed and replaced with a page reading “Ken suddenly realised being in the idol industry was a really stupid idea and went back to being a gangster” nothing of value will be lost.

Thank you for providing the missing paragraph of my post: you really perfectly nailed how off the idol arc is.

Like you say, just a horrible mess (and you’re also right the final fight makes no fucking sense at all). I didn’t mention it in the essay but I’ve wondered if the idol arc was one of those desperate bids to move Sun-Ken Rock higher in the Young King ratings, or else the influence of a new editor or something. All of it is clearly in Boichi’s wheelhouse, but you’re really right about how it’s terrible in a lot of different ways.

Good lord Jeff you are an embarrassing white knighting cuck. Women don’t need you to protect them, and more likely than not are laughing at your pathetic attempts at male feminism while f$&@ing an actual man instead.

LMAO. This. Cuckolds are so fucking sad

I don”t know if many people will see this

But honestly thank you for your article. I find it weird that Sun Ken Rock can get away with portraying rape this way.

It is one thing to portray rape (like in berzerk for example) where its simply depicting it because it happens in the story

Here in Sun Ken Rock, it feels like every situation is a good excuse to squeeze in rape, but more importantly, it’s done in a manner very resembling of hentai, meaning a lot of the time these scenes of rape are going to be glamourised

A rape scene is supposed to be a horrific scenario, in Sun Ken Rock it feels like it was drawn to arouse

I was happy at first bc I thought the manga would cover sexual slavery with some seriousness but apparently that is not their plan

Many years later I totally agree with you:

https://myanimelist.net/reviews.php?id=483631