Read in 2017, by anyone who’s even the least bit aware of… well, the cultural context of 2017, to put it bluntly — I almost wrote anyone who’s even a little bit woke, but that term feels odd coming from the fingers of a 43-year-old Scot — it’s inescapable how oddly limited Watchmen is, in terms of cultural outlook. Yes, it features everyone from Nice Guys to Omnipotent Men and Smart Men and… well, you get the picture, but it’s unmistakably the work of two straight white men of similar ages — Moore is four years younger than Gibbons, surprisingly, despite permanently seeming the older of the two — and upbringings, which is to say, “mid-20th century English.”

It’s clear, for example, that Watchmen is an especially white book. There are those who’d argue, pointing to Bernie — the kid at the newsstand — or Malcolm and Gloria, Rorschach’s psychiatrist and his wife, as evidence that that’s untrue, because three whole black characters with names is a big deal, right? Except, of course, two are essentially glorified cameos, with only Malcolm getting any kind of inner life of any kind, and even then, it’s one that shows how easily he’s bullied and pushed around emotionally and spiritually by the white man he’s dealing with. Similarly, Bernie’s role is apparently to be lazy, get shouted at by the white guy running the newsstand and say things like “sheee-it!” while calling people “turkey”; he’s literally an uncomfortable stereotype dropped into the book, hilariously, as a framing device for a story about another white guy who is more complex than he is, despite being a comic book character inside a comic book.

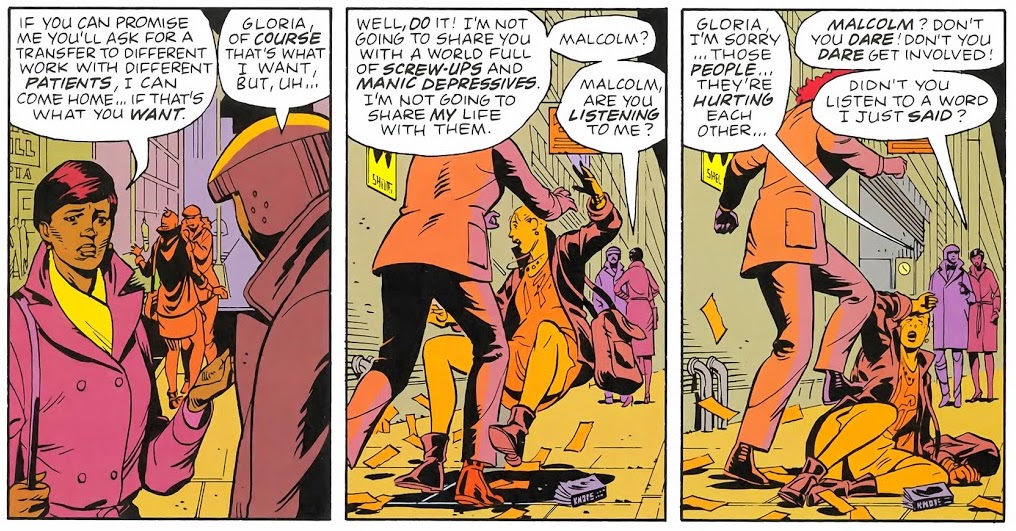

(Gloria, at least, gets to be… what, impatient, selfish and difficult to talk to? Yeah, that’s much better. Oh well, there’s also the unnamed mailman and some random thugs when necessary. Yeah, nothing wrong here at all.)

There’s also the story’s treatment of lesbians, which is… “problematic,” I believe the phrase is. Silhouette, one of the Minutemen from the book’s backstory, is the subject of gossip-y discussion in the book’s back matter — where we learn that her and her lover’s murder is deemed less serious than the original Silk Spectre quitting the team (Literally, from the Under The Hood text: “In 1946, the papers revealed that the Silhouette was living with another woman in a lesbian relationship. Schexnayder persuaded us to explore her from the group, and six weeks later she was murdered, along with her lover, by one of her former enemies… in 1947, the group was dealt its most serious blow when Sally quit crimefighting to marry her agent”), and that Sally Jupiter didn’t like her, but her sole line of dialogue in a flashback sequence is her being bitchy to Sally, as if to suggest that Sally was right all along.

Of course, Silhouette is just a ghost in the book’s back pages for the most part; there’s also Joey and her girlfriend, two of the regulars at the newsstand whose relationship is at best dysfunctional, at worse abusive. Unable for either to properly communicate, their storyline dies when Aline is on the ground, being beaten by Joey, whose self-loathing — “And I buh-wanna be straight… and, and I wanna be dead…!” — has erupted outwards.

There’s an argument to be made for the idea that, well, at least Moore and Gibbons tried to be inclusive and therefore should be applauded (Jeff, I think, made it when we talked about Watchmen awhile back, before I wrote this series), but… Really, I don’t buy it. Lesbians are figures of dysfunction and disdain in Watchmen, and black people are there to be harassed and used as props to illustrate the stories and struggle of the white men around them. Is that really inclusion? Is that any different from the only black faces in movies being servants or slaves or comic relief idiots?

Really, though, Watchmen is the story of white men being white men. There’s something prescient about Dan’s throughline at Nite Owl — he’s a nerdy white guy who the girl falls for because he’s nice, laying the groundwork for countless pop cultural takes on this idea in subsequent decades — as well as the book’s strange hero worship of the Comedian (a character that every single character seems in awe of, despite their different viewpoints on almost every single other thing, to the point where even the woman he raped loves him, a character beat that to this day feels beyond creepy and unnecessary) and distrust of the intellectuals Ozymandias and Dr. Manhattan. The journey of various white male archetypes across the last 30 years feels visible in Watchmen, and I can’t tell if it’s because Moore and Gibbons were successful in predicting the future, or that they laid out a map in this series that larger culture has learned from and unwittingly accepted given the impact Watchmen had.

And, in the end, that was what Watchmen felt like to me: The ultimate “Toxic Masculinity” comic, the urtext of countless Men’s Rights activists and red-pillers who can look at this and hold two thoughts in their heads: that this is as good as comics get, and that men — white, straight men — have it so much worse than anyone else could ever understand, but only a lone visionary standing against the crowd can save the world. Whether that’s the Comedian, Rorschach or Ozymandias — the first two fail, of course, although that’s arguable given the epilogue scene — is open to question, but it almost doesn’t matter. Watchmen is a book that can appeal to anyone who’s white, straight and believes they know better than everyone else. An attitude that really is, when it comes down to it, quintessentially mid-20th century English.

Read today, however, the politics — social, far more than the purposefully blunt, comedic party politics — look fragile, brittle and unconvincing. As with all important cultural artifacts, it’s not only a product of its time, but something that should be revisited on a regular basis, and re-evaluated. Watchmen is unmistakably an ambitious work, and one that had the kind of impact on the industry and arguably the medium that is almost unimaginable. But it might be time to accept that it’s flawed, dated and ready to be replaced as the be-all and end-all of the superheroic genre.

The only question is, by what, and from where?

Graeme… you really need to let this go.

I must admit I’ve been enjoying it. I don’t entirely agree with all of this one, but there’s some important stuff in there.

And it’s the most Scottish commentary on Watchmen that I’ve ever read. And that includes the commentary on Watchmen that is everything Grant Morrison has written since 1987.

As someone who’s liked and retains affection for Watchmen this is a useful perspective and will have a permanent effect on how I talk about the book. While it doesn’t undermine Graeme’s argument about how to look at this now, I’d be interested in which were the more ‘woke’ superhero stories of the 80’s. One thing I do like about the story is that class is considered.

I presume that no single work will replace Watchmen, just because the field’s bigger and more diverse.

Watchmen has some shaky chunky dialogue. Moore is most like King in that his dialogue should never be spoken aloud.

I think that the plotting gets incredibly ropey around the 5th issue too. The precision of Watchmen is mostly on Gibbons side.

Moore always just assumed his audience never read anything but comics so he just stole stuff from novels he liked and crammed it in. His success and acclaim might mean he was right.

Watchmen’s characters had the depth, clarity, and kink of Uncanny X-Men at the time except they got to use explicit language. They had fantastic designs. There is enough that I want to see what happens to them in Doomsday Clock. Whatever problems I have with Watchmen as a text or my memories of Watchmen as a text I can’t deny the characters as good pulp superhero characters.

Watchmen is half solid murder conspiracy, half all over the place, by the way, psychics exist in this world we should have set that up better, and then a fake monster explodes. That back half just does not flow (to me.) The pirate story is never not a slog and why I have a hard time when people say that Watchmen is really an optimistic work. Watchmen is good because of Moore (League is probably his best and most honest work), great because of Gibbons, weirdly at odds with its insisted verisimilitude by Higgins psychedelic mud palette. Its high-minded pulp, not fine lit.