Even if it hadn’t been the first book to arrive at the library, Before Watchmen: Minutemen/Silk Spectre would have been the place to start on this revisit. (Well, part-revisit, as I said before.) The two series collected in the hardcover are, chronologically, the earliest in the expanded Watchmen timeline; this, in theory, is where it starts (There are flashbacks to earlier elements throughout other stories, and the latter mini-additions to Before Watchmen — the Moloch mini and Dollar Bill oneshot — take place earlier, but we’ll get to all of them later).

Of course, it’s not where it starts, really, and that’s perhaps where I should start: A lot of Darwyn Cooke’s Minutemen isn’t just prequel or prologue, it’s an outright retcon — Cooke takes the characters as established — or, more properly, briefly sketched — by Moore and Gibbons — and, in many cases, significantly rewrites them by expanding upon them, transforming in the process from Moore’s obsessions and recurring themes to Cooke’s. (One of said changes: Women have a far less passive role in Minutemen, which leads to a significant shift in the portrayal of Sally Jupiter.) It’s clear from the very beginning that this isn’t Cooke trying to recreate Watchmen in any appreciable way, and especially not formally — everything about Minutemen feels far closer to Cooke’s DC: The New Frontier than the work it’s actually building off, from layouts, pacing and dialogue to, most importantly, morality.

Watchmen is, to me, an essentially amoral book — I’m sure many would disagree (including Jeff of this very parish), but Moore seemed to at least be hinting at that in the interview that made up the 2003 Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore book when he said, “I didn’t want to make any character the one who’s right, the one whose viewpoint is the right viewpoint, the one who’s the hero, the one who the readers are supposed to identify with, because that’s not how life is… it’s up to the reader to formulate their own response to the world — sort of — and not be told what to do by a super-hero or a political leader or a comic-book writer for that matter.”

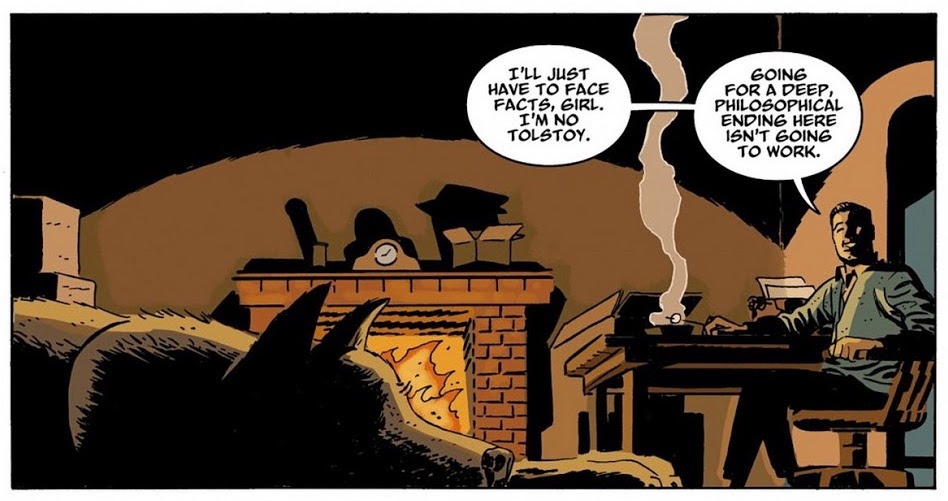

Cooke strikes me as a creator who is incapable of producing such a thing, however — arguably, he attempted with the Parker books, but those are adaptations and even so, had a particular morality to them — and certainly isn’t even trying with Minutemen; the book is told from Hollis’ point of view as he writes Under the Hood, although Cooke’s narrative voice doesn’t match Moore’s excerpts of the book at all, and is shot through with the need to do the right thing that drove [Cooke’s version of] Hollis. Moreover, that morality infects almost everyone else in the book, in ways that are at odds with Moore’s Watchmen writing; watching the Comedian try to talk Sally Jupiter out of killing someone because of the emotional cost she’ll pay after feels almost quaint, and out of character considering everything else surrounding the characters as established by Moore.

It’s also out of character considering other Before Watchmen books, but let’s leave that ahead of us for now.

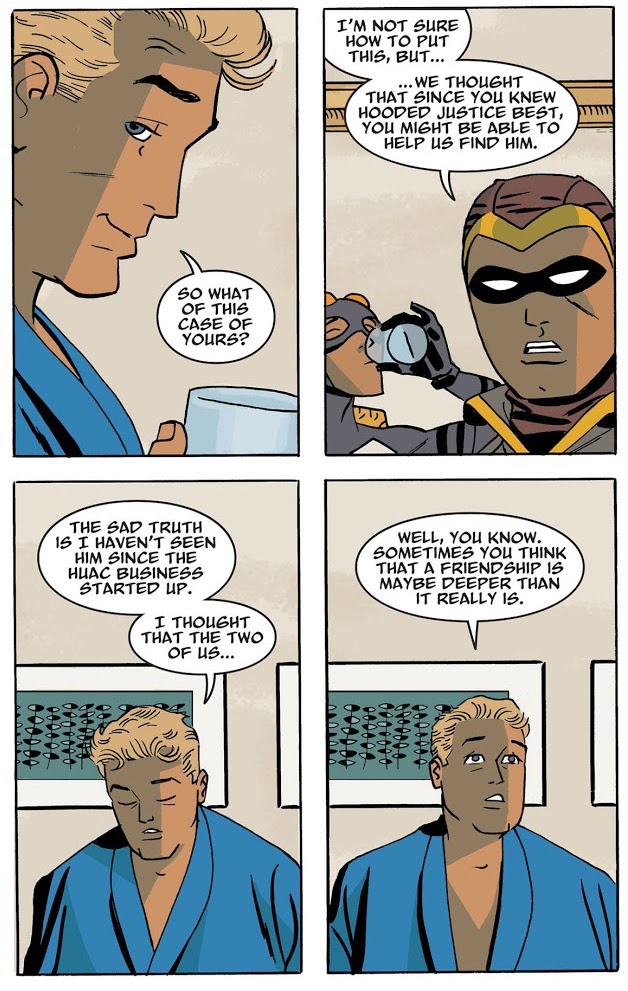

I said, “almost everyone else” purposefully; while characters like Silhouette, Dollar Bill and even the Comedian get some redemption in Cooke’s hands, Hooded Justice gets just the opposite, in the name of a feint at the end of the story. Building off the costume’s noose gimmick, he’s shown indulging in what appears to be non-consentual BDSM midway through the story in service of a plot that sees Hollis — and the reader — become convinced that he’s actually the serial killer that the heroes have been hunting for throughout the entire series. It leads to Hollis killing Hooded Justice, only to be told by the Comedian afterwards that the evidence was faked in an attempt to draw out the hero who had otherwise gone into hiding.

I said, “almost everyone else” purposefully; while characters like Silhouette, Dollar Bill and even the Comedian get some redemption in Cooke’s hands, Hooded Justice gets just the opposite, in the name of a feint at the end of the story. Building off the costume’s noose gimmick, he’s shown indulging in what appears to be non-consentual BDSM midway through the story in service of a plot that sees Hollis — and the reader — become convinced that he’s actually the serial killer that the heroes have been hunting for throughout the entire series. It leads to Hollis killing Hooded Justice, only to be told by the Comedian afterwards that the evidence was faked in an attempt to draw out the hero who had otherwise gone into hiding.

It’s a heavy-handed development — although perhaps not as much as when the mysterious new hero who helps the team prevents Japanese terrorists from causing nuclear apocalypse in New York City turns out to be Japanese because, hey, it’s bad to generalize an entire race of people, which also happens. It’s also an ugly and unnecessary one that accomplishes nothing beyond an ugly “Gotcha!” — the reveal happens after Hollis had retired and completed writing Under the Hood, so it’s not even as if it was the motivating factor for either event. Instead, it just demonstrates, not for the first time, how fallible the heroes in the book turned out to be.

(When talking with Jeff about this book, earlier, he said that he remembered that the Hooded Justice plot had drawn people to accuse Minutemen of being homophobic; I don’t think that’s the case — the treatment of Silhouette and her lover throughout would act as an argument against that, I think — but, especially if the complaints came before the final reveal, it’s certainly a thread that invites criticism for its ugliness and the manner in which it seems Hooded Justice is somehow uglier than every other character in the storyline.)

(A second aside, for a second; Hooded Justice’s treatment in this book is curiously reminiscent of Rorschach in the original Watchmen, and I can’t work out if that’s intentional or not, and whether or not Cooke was trying to hint that Hooded Justice was similarly mentally impaired. That, too, would be likely to draw criticism if it were the case.)

Overall, Minutemen feels like a warmer book to me than Watchmen — and than the other Before Watchmen series, for that matter, Silk Spectre aside — although that might simply be because I’m more personally attuned to Darwyn Cooke’s grouchy sentimentality than Moore’s curmudgeonly hippieness of the 1980s. As the first part of this whole expansive reading project, it worked well for me; I felt like I had an emotional “in” to the world that had been missing before, and I found myself wanting to read more. Which, considering the next thing I read was Silk Spectre, turned out to be a good thing.

[Disclaimer: Have never read any part of Before Watchmen, am almost certainly never going to.]

How would you respond to the obvious counterargument, that Cooke’s sentimental nostalgia is always inevitably too “soft-focus” in its treatment of the past and is the reason why you have such ham-handed bits as “Look, the hero is also Japanese!”?

Because Cooke knows that there are all sorts of problems with soft-focus nostalgia, and so feels that he has to “put in” these qualifiers to correct it, but they always feel discordant and clumsy because idealization of “a better, simpler time, when men were men” is marbled throughout the whole way in which he approaches this sort of material. I find his choice of Hollis as his main character a little revealing.

While Watchmen itself is thoroughly anti-nostalgic in its approach to the past – at the same time as it allows itself to be sympathetic to characters who are nostalgic. This is where I would disagree with your characterization of it as amoral – that comes across to me as humane, and is one of the things that I like about Watchmen. It doesn’t give the reader any hero to endorse, but it doesn’t have any villains, either. It tries not to withhold sympathy from any of its characters. Cf. your recent discussion of empathy.

It goes wrong in lots of *other* ways for me, but not that one. Although its most serious and notorious flaw (the treatment of rape) is connected to it, so, for me, one can absolutely say that Moore’s pursuit of an agenda of not withholding sympathy causes him to fall into doing something that is simply indefensible.

Your voice on comics (Graeme), Jeff’s and Matt’s are so cool to read and listen to I’m always craving more. I’m especially happy when you cover popular works. Watchmen even ancillary Watchmen is one the few comics I know and can follow. I love this project you are doing.

I’m happy you are doing this, Graeme. It’s pretty interesting to read about with Doomsday Clock coming up.

http://watchmen2creatordarwyncooke.tumblr.com/

The above is probably unfairly nasty in the passive-aggressive Abhay parlance, but it’s hard to square these quotes with, well, the above comic. So what happened? Well, I have heard in Cooke’s case, he was pretty pissed at all the slagging off Moore was doing of his contemporaries and the current comics scene.

That’s the only way this makes sense to me: that Cooke at least, and maybe Johns, just want to stick the knife in the old man, that old man being Alan Moore, once and for all.

I feel weirdly sympathetic to this argument, but also, well… why let what the old man says bug you?

I avoided, and will continue to avoid, these books like the plague. That said, this was the only one that tempted me, solely because of Darwyn Cooke’s art.