Before Watchmen: Rorschach was, I think, the series I was least looking forward to in the entire Before Watchmen cycle (with the possible exception of Crimson Corsair, which I’ll get to eventually). I was wary for all kinds of reasons, from a creative team that didn’t particularly interest me to the 1970s setting that felt cliche. Most off-putting of all, however, was the central character.

I know that I’m supposed to find Rorschach compelling, or at least interesting; he gets an issue in the original miniseries dedicated to how fascinating he’s supposed to be — scary enough to shake the self-belief of his experienced therapist, despite how stereotypical his backstory is, apparently — but he’s always fallen flat for me; an character whose appeal lost its luster when it served as much as a model for certain schools of thought about Batman’s psyche as it did a parody of Steve Ditko’s Mr. A and the Question. The prospect of a mini-series by Brian Azzarello and Lee Bermejo spending time with that guy? No, thank you.

The surprise of Rorschach, then, is that the lead character may share a name, mask, and freckles with Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ character, but he’s not the same guy. The difference isn’t just the eight-year-gap between stories, either; the Walter Kovacs that appears in the Rorschach series has more in common with certain readings of Marvel’s Punisher than the fragile figure Moore and Gibbons delivered, and his series — separated from the other tropes and flavors of Watchmen — feels more like a generic retro thriller that glorifies exploitation stories from the 1970s without noting that the original versions of those stories tended to put someone other than a straight white dude at their center.

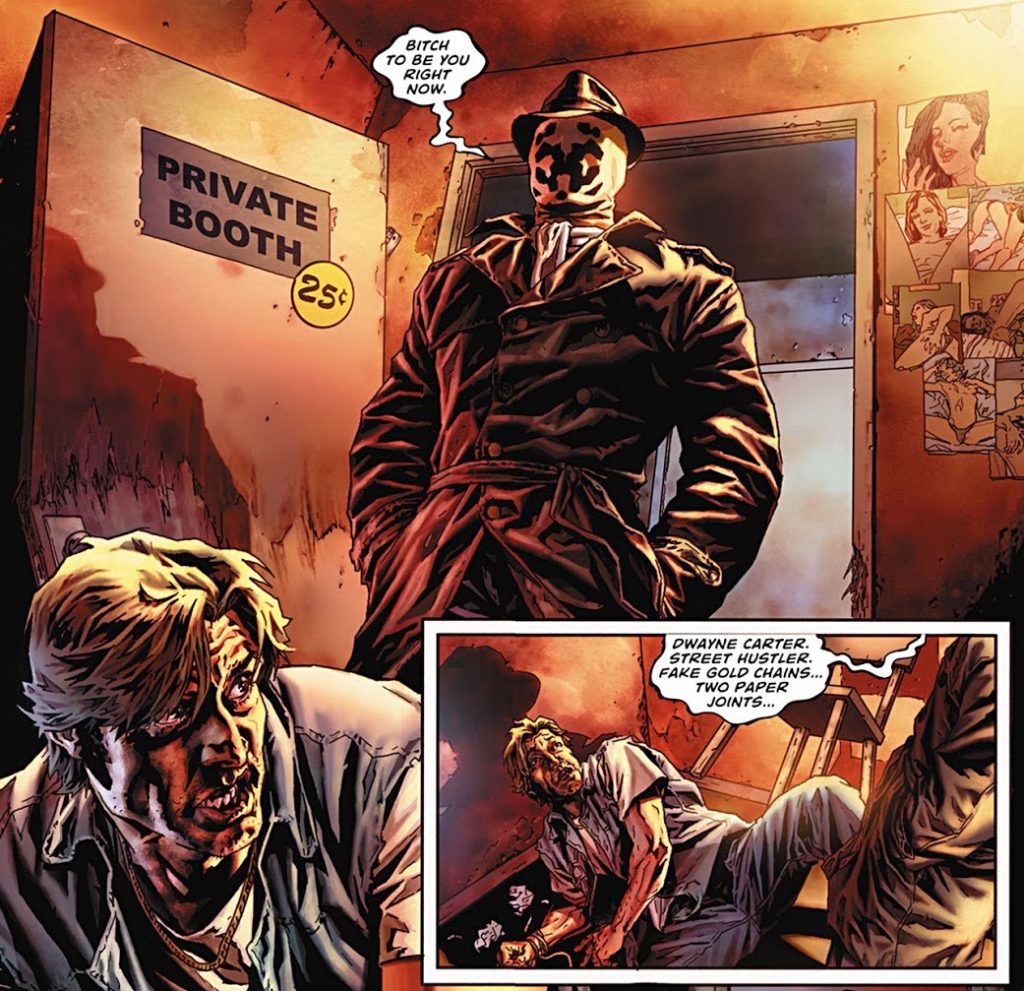

(The racial politics of Rorschach are one of many sticking points to me, muddied only slightly by the indistinct coloring that makes me wonder whether the main villain, Rawhead, is supposed to be white or not; nonetheless, a book where the white guy complains about the rest of the world falling to savagery and corruption and the majority of those he’s fighting are people of color is a very bad idea.)

Narratively, the series disappoints because it buys into the simple morality of the character a little too much for my liking, offering up something that argues as much for might makes right and an overwhelming element of chaos as anything else; a worldview that many would embrace as valid, if not realistic, but one that doesn’t necessarily make for a satisfying read. What to make of the serial killer who opens the series, but goes essentially unexplored for the majority of the story, only to assault the woman Rorschach was potentially interested in, leading to a final sequence where he takes revenge behind a window blind?

Indeed, what to make of that romance plot, which isn’t exactly a romance plot — does he ask Nancy to dinner because it’s a date, or to thank her for taking him to the hospital? Ultimately, it becomes the most obvious Women in Refrigerators riff, but stripped down in such a way as to lampshade how cliched it is. Is this… metacommentary? Laziness? Somewhere in between?

Nancy, of course, is just one of an army of bit players throughout the story, lending little (if not nothing) to proceedings beyond schtick and whatever awkward plot contrivance is required of them. While Lee Bermejo and colorist Barbara Ciardo try to instill some weird semblance of life to each of them in an art style that feels far too realistic for this world, both in terms of Gibbons’ aesthetic in the original series and Azzarello’s cartoonish writing, there’s nothing to be done; Rorschach himself may come across as more two-dimensional than his earlier incarnation in this series, but he’s still infinitely more complex than everyone around him.

Amusingly — or, perhaps, exactly the opposite — after all my complaints about the real world figures making cameos in Azzarello’s Comedian, perhaps the most egregious moment in Rorschach is a cameo of a fictional character: at one point, Rorschach is rescued by none other than Taxi Driver‘s Travis Bickle, who complains about the state of the city as one might expect. Taxi Driver came out a year earlier than when Rorschach is set, which ends up nagging at me for reasons I can’t fully explain: did he know he got the dates wrong? Is there some meaning there? Is it just a lazy mid-70s gritty New York story in-joke that I’m reading too much into?

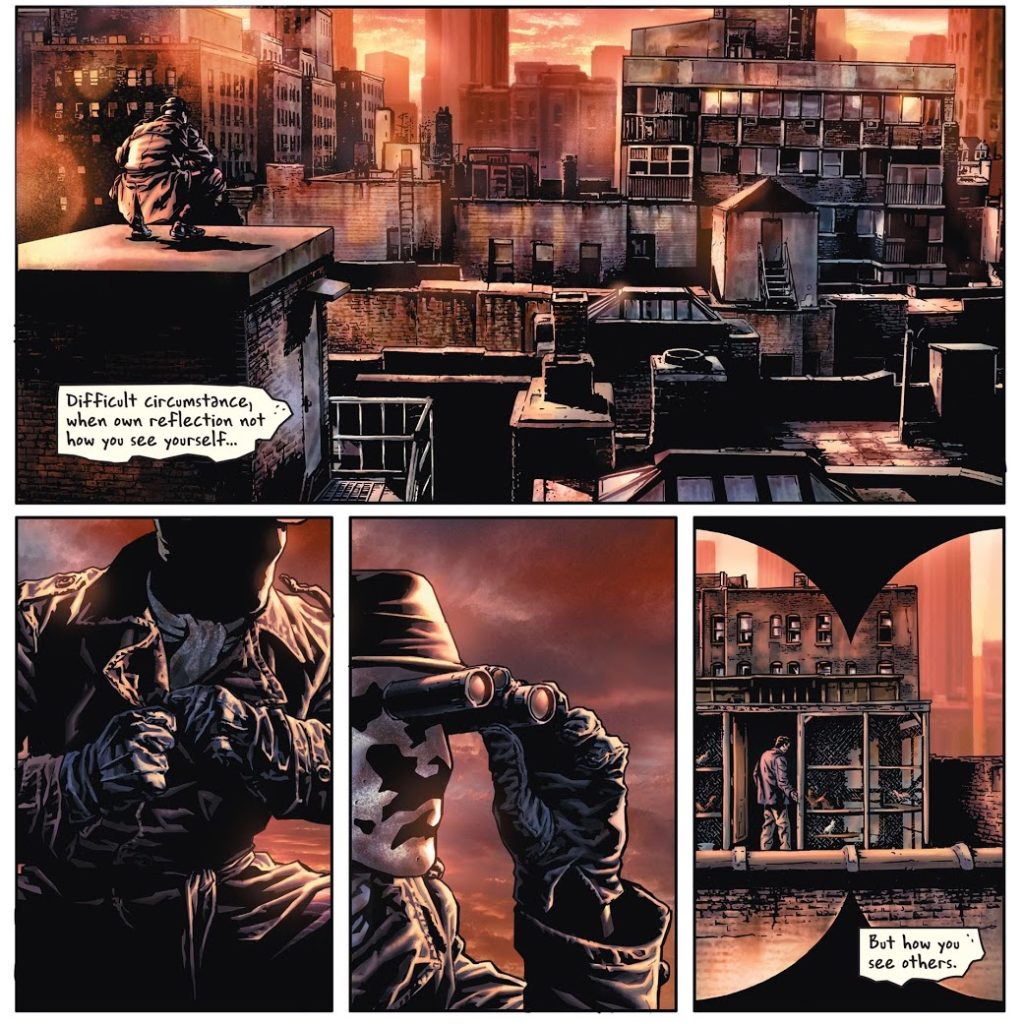

Talking of the era, it still seems strange to me that Rorschach is set during 1977, and makes almost no reference to the events referenced as taking place during that year in the original Watchmen. 1977 in Moore and Gibbons’ book isn’t just another year — it’s the year the Keene Act was passed, outlawing vigilantes and costumed crimefighters, following riots caused in part by police officers striking because they felt that they were being undermined by superheroes. Rorschach was the one vigilante to refuse to go along with the law by either retiring or working for the authorities… and this is barely hinted at in Rorschach, inexplicably, despite the fact that it would have to be happening around the exact period this story takes place during. (The panel above is pretty much the sum total of its impact on the series.)

(In a smaller, less important moment of discontinuity, Rorschach as seen here feels out of step with the version seen at the end of the Nite Owl series, who has already started carrying around the “End is Nigh” sign he’ll still be holding in 1985, when the original series opened. Perhaps we should just pretend that this series happened on Earth-Watchmen-2 or something.)

Is Rorschach a missed opportunity? I can’t say for sure, because I’d be lying if I said it felt like much of an opportunity in the first place. It certainly is something that fails on almost every front, however, and abandons the chance to try to deepen its central character in favor of something that’s a minor work on behalf of both of its primary creators. As its central character would put it: Hurm.

If Graeme’s review whet your appetite for more withering scorn against a very, very, plump target, then might I recommend Colin Smith’s review of issue #1 to you? Colin was, if anything, more frustrated by this comic: http://toobusythinkingboutcomics.blogspot.ca/2012/08/on-rorschach-1-thursday-review.html