For all of its formal playfulness — which attempts to embrace the spirit of Watchmen‘s “Watchmaker” issue, even if it doesn’t quite hold itself to the same standards of obsessiveness wth regard to detail — Before Watchmen: Dr. Manhattan is a confounding series, for multiple reasons, not least of which is that it’s a massive “What If?” that sprawls across four issues without actually accomplishing anything of value, while also drastically changing the continuity of the Watchmen universe.

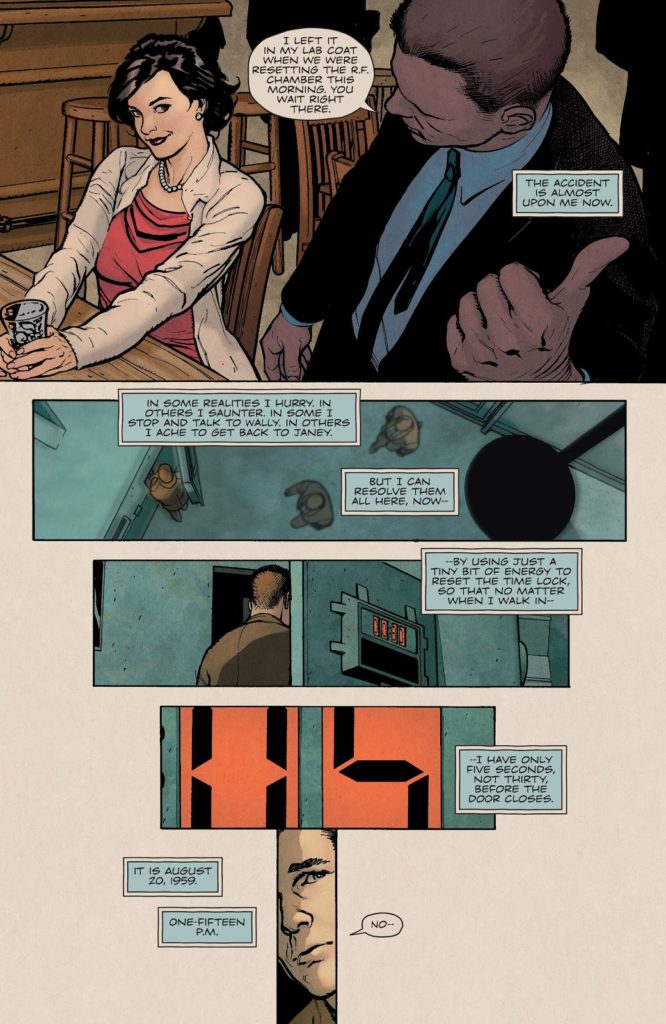

The gimmick of the series, so to speak, is that Dr. Manhattan, to quote Kurt Vonnegut, has become unstuck in time. Or, more properly, he unsticks time; in revisiting his past during the first issue of the series, he revisits the moment he went from Jon Osterman to Dr. Manhattan, only to discover that it doesn’t happen.

The gimmick of the series, so to speak, is that Dr. Manhattan, to quote Kurt Vonnegut, has become unstuck in time. Or, more properly, he unsticks time; in revisiting his past during the first issue of the series, he revisits the moment he went from Jon Osterman to Dr. Manhattan, only to discover that it doesn’t happen.

It’s the first retcon in a number of retcons in the series, a series that seems to exist to retcon everything in its own way. Oddly enough, there’s something about this idea — and about the exploration of alternate timelines where the past behind the world of Watchmen didn’t happen, or happened in an altered state, with the differences seen side-by-side or playing out on the page in more subtle ways, revisiting and recurring — that feels fitting for Dr. Manhattan, the one actual superpowered member of the Watchmen cast, and the one who is, essentially, God.

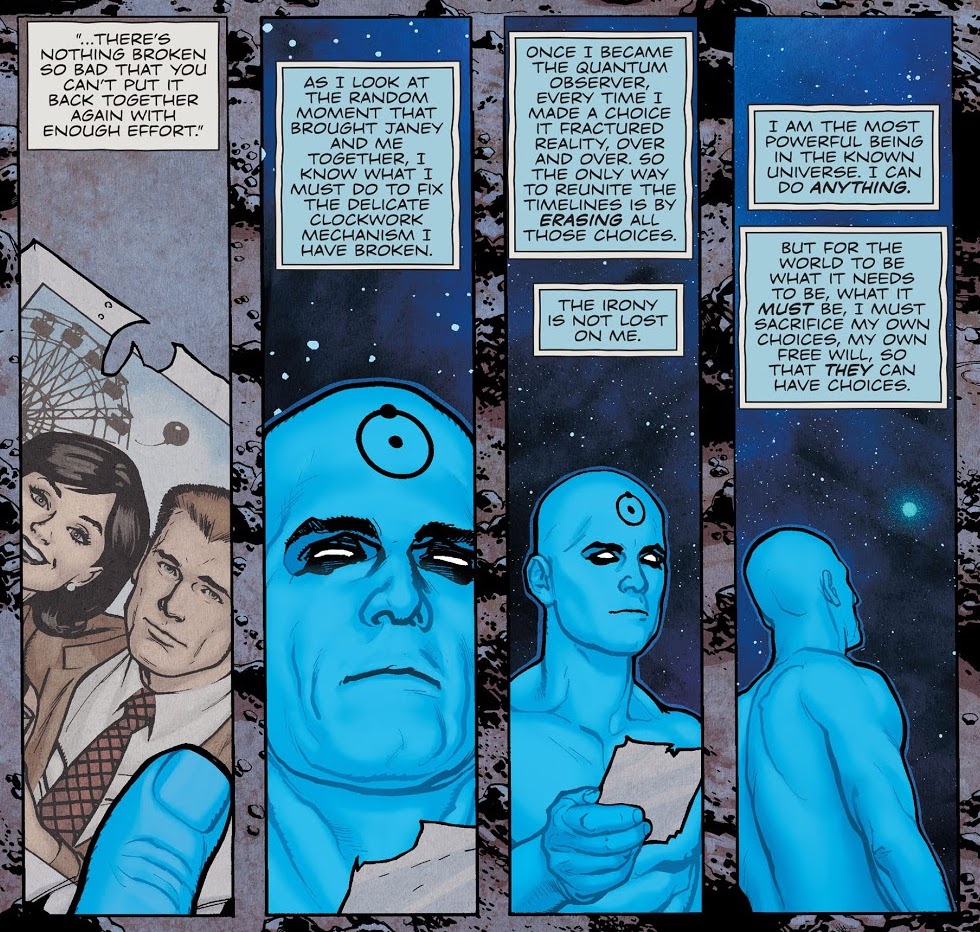

The plot, such as it is, of the series is that Dr. Manhattan, by witnessing history, alters history so that his accident doesn’t happen — there are so many Schrödinger’s Cat references that it’s impossible to miss that J. Michael Straczynski has read up about the observer effect and quantum theory a little and wants to show off — leading him to revisit different areas of his past, from childhood forward, and see things unfold in slightly altered ways. Ultimately, he realizes that he has to force the accident to occur, but doing that doesn’t restore everything to the way it previously was… which brings up the final, most important, retcon of the whole thing.

Dr. Manhattan isn’t, actually, a Before Watchmen book in anything but name. For one thing, the Dr. Manhattan at the center of the series comes, chronologically from after the events of Moore and Gibbons’ story (At least, I think so; it’s unclear, but he certainly seems to have memories of the end of the Moore/Gibbons story even after that timeline has been overwritten, which would seem to suggest he’s from the end of that story). For another, it’s a series that actively overwrites not events from the original series, per se, but perspectives and meanings — everything still happens as it originally did, but the free will of the characters is at least undermined, if not in some cases, in arguably the most dramatic case, removed entirely. And, finally, there’s the fact that Dr. Manhattan actually extends after the end of Watchmen #12, in that we see where Manhattan went after he left Veidt in that issue.

There are problems all throughout Before Watchmen in terms of continuity — things that seem at best out of synch, if not outright contradictory. Compare the Comedian’s behavior in Minutemen to his behavior in Comedian, say, or Rorschach in Nite Owl and Rorschach. For all that it plays about with continuity and the re-writing thereof in Dr. Manhattan, it’s something that speaks to these problems. If this book is to be believed, Manhattan has to repair the timeline by implanting Veidt’s plan in his mind during their first meeting — a significant change to Watchmen and its mythology, because it actively robs Veidt of the responsibility for what he does in the name of world peace. But, elsewhere in Before Watchmen, the Ozymandias series has Veidt come up with the plan before that meeting. Are we supposed to believe that that timeline was overwritten, leaving Manhattan to try and repair it by implanting the plan at a later date? Perhaps, but Ozymandias also suggested that pieces of the plan were already in motion by that later date, meaning that Veidt must have played a dramatic game of catch-up in order to keep everything on schedule.

Or else, you know, writers and editors weren’t exactly paying the closest attention to what was going on in each series, and how they related to each other. Shit happens.

You might have noticed that I’ve avoided actually saying anything about the quality of the series, of whether or not I liked it. There’s a reason for that; I don’t actually know. The art, by Adam Hughes and Laura Martin, is beautiful; luscious and inviting, and filled with character while avoiding the cheesecake offered by the first issue’s cover. The story, though… is just there. It lies on the page, reading as much as anything for me like Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman issues in terms of tone and lifelessness. While there are, technically, cosmic scale issues at stake, it’s impossible to become emotionally connected with them, even on a comic-book-event level, because there is nothing after this for it to impact. It’s not like it’s Zero Hour or Crisis on Infinite Earths; if continuity is changed, what does that matter? There’s literally no more story after this to explore what that means, if anything. There’s literally no point to changing history, other for the bragging rights of having done so.

There are meta concerns to changing the continuity, I guess; I can imagine people wondering if it’s an attempt by DC’s hive mind to wrest control of the original Watchmen further away from Moore and Gibbons — a charge that doesn’t resonate to me, although I think Before Watchmen is ultimately an example of bad faith on DC’s part over all, displaying at the very least that it believes the original will never go out of print, if the rumors about the original contract are true — or, in some people’s eyes, laying the groundwork for Rebirth and Doomsday Clock. That seems even more outlandish, given that Rebirth was four years away when this was published, and likely not even an idea in Geoff Johns’ head at the time. (Also, having seen much of Doomsday Clock #1, I suspect that there’s even a possibility that Dr. Manhattan as a series will be utterly ignored by Johns and Gary Frank in the new book.

In terms of story, then, I’m left cold by Dr. Manhattan in both intent and execution. For all its clear desire to be saying something, it turns out to be nothing more than a pretty distraction that turns out to be empty of meaning. There’s probably a metaphor here about clocks falling into sands of Mars, but after making it through four issues of J. Michael Straczynski’s attempts to recreate Alan Moore’s none-more-cosmic narrative voice, the last thing I want is more pretty language that isn’t actually saying anything, even from myself.

My first thought was that this series was part of some early attempt by DC to set things up for a Watchmen sequel – specifically Doomsday Clock. But you make a good point about it having come out so long before Rebirth.

I guess then that makes it yet another of Straczynski’s attempts to explore themes around origins and giving godlike characters the role of creator within the narrative. It’s not that I mind that idea on its own – sometimes a “I have to go back in time and create the present that I left” story can work. But I’ve always found that Straczynski himself has nothing inherently meaningful to say about that idea.

His Spider-Man/Ezekiel stories, for example, added the layer that perhaps Peter had received his powers from a mystical spider-totem, an idea that I think fundamentally breaks the character. But you could argue that it adds an interesting layer to the character’s story. Except JMS himself completes the whole story cycle by having a mystic character saying something like, “Whether the sun rises because of God’s will or because it just does, what really matters is that it rises” which just seems like the most dull, lifeless conclusion to a story ever.

Sounds like Dr Manhattan offers a similar defeatist climax: Sure, Dr Manhattan could’ve changed things, but he didn’t, which led readers to where we were before he changed things. That makes the story itself moot. Why does it exist? Why did we read it? What did it have to say about Dr Manhattan or Watchmen or JMS or human experience? It’s kind of cynical and defeatist. It’s no wonder then that JMS ended up writing a Superman who didn’t want to help people because helping people felt meaningless and like it wouldn’t have an impact on anything or anyone.

I’ve heard scuttlebutt that Straczynski- at least at Marvel- had a very ironclad “don’t change anything” clause in his contract (although the Stacy twins being Osborn’s kids instead of Peter’s was the one thing they made him change), which would account for his seeming ignorance of the other books- he just doesn’t care, and editorial can’t do anything about it (it certainly would explain a LOT about his Spider-Man run, with plotting mistakes that could have been fixed with a simple sentence).

Note that during his tenure at DC, outside of the disastrous Superman and Wonder Woman runs he did stuff like the Earth One Gns.