Sometimes “capsule reviews” is just code for “hey, here’s what I’m reading that you might be interested in, even though I don’t have anything like the laser hot insight I brought to comic books with gorillas riding horses.”

Join me after the jump for an embarrassment of riches! (and by “riches,” I mean “embarrassments.”)

Star-Lord: Guardian of the Galaxy (part 2 of 2): Okay, this went back to the library with me making no more headway than a few pages past the stuff I read previously. While I felt those few pages I did read by Claremont and Infantino were interesting in that the Star Lord found there was much, much cockier than in his previous appearances—and therefore a better bridge to our current incarnation of Peter Quill than I had expected—of all the Claremont character types, I think I dislike his cocky character type the most. Bless his heart, if there’s one thing he doesn’t need, it’s a Claremont character who’s driven to talk even more.

Sorry, everyone! Clearly, the worst way for me to get reading done is to announce what I’ll be doing beforehand.

Forward, Teen Psychic Squad!: Meanwhile, over at Crunchyroll, there’s Present for Me, a collection of seven short manga from Masakazu Ishiguro, whose Soredemo Machi wa Mawatteiru (also known as And Yet The Town Moves) is officially Jeff’s Favorite Manga of the Last Year He Has Yet To Figure Out How to Write About. SMwM is understated character comedy that dips its toes every so often into goofing on genre tropes. (About forty chapters in, Ishiguro does a ghost story mystery riff that’s funny, intriguing, and scary…and yet also still funny.)

So it’s no surprise I enjoyed the first story in Present for Me, “Forward, Teen Psychic Squad!” a goof on the “ordinary people with extraordinary powers recruited by a mysterious organization” genre that starts immediately after an explosion has wiped out the organization’s island laboratory, the organization, and forty percent of the team. In doing so, the story really reveals itself to be a goof on the “strangers stranded after a disaster trying to survive” genre.

Low-hanging fruit, sure, but half the fun is how much work Ishiguro puts into a stupid joke with a really stupid climax. I dug it.

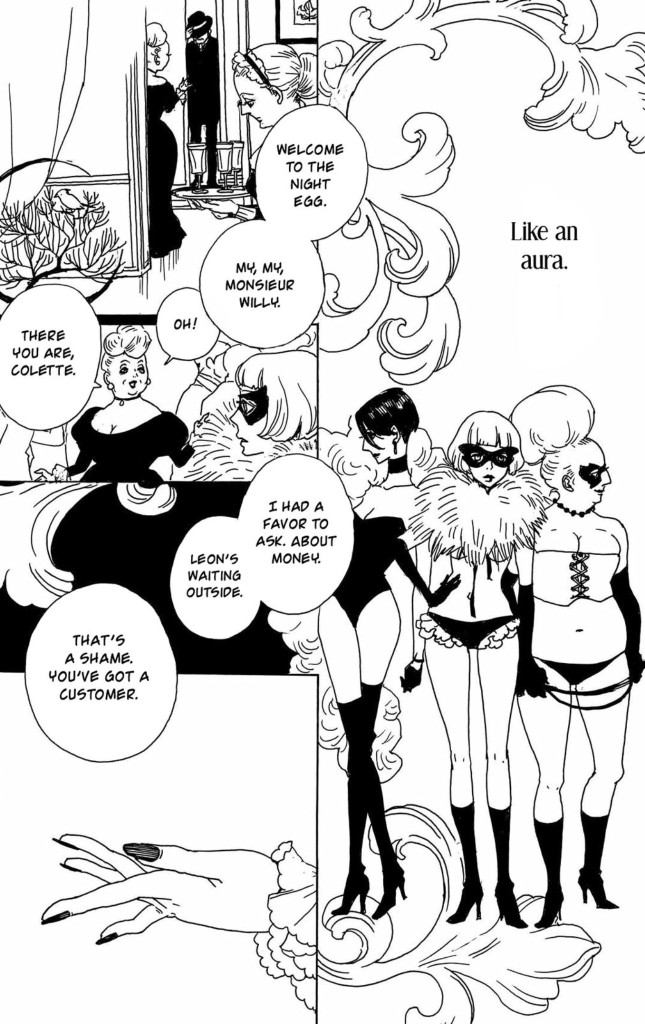

Memoirs of Amorous Gentlemen: Also at Crunchyroll are seven chapters of this period manga about a brothel worker in Paris in the early part of the 20th century. I’m not proud to admit it, but I’m totally a sucker for “pretentious twaddle with boobs.”

But considering the boobs are mostly corseted and the twaddle seems to be stuff swiped from Colette and Balzac, this material is either far less embarrassing or far more embarrassing than I make it out to be. Also, Moyoco Anno has breathy linework she sets on the page without a lot of bolstering inks that heightens the story’s conceit of the tales being recounted in a diary by one character or another. I get the faintest Crepax vibe off the art although I think that’s because there’s so much overlap on the iconography (flapper haircuts and lingerie), instead of an actual artistic influence at work.

I have no idea how many episodes were originally done, or how many Crunchyroll intends to run–it very much seems like a passion project for editor/translator/letterer Andrew Cunningham? But if there were, like, 87 volumes of this, I’d read them all until my eyes collapsed in on themselves.

Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen: Sequential is just finishing up their month-long summer sale, a sale which finally allowed me to catch up with what all the cool kids are reading last year and the year before. Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen, as most of you are probably aware (because I assume you’ve been reading the Interent since 2012 or so), is the long-time-coming graphic novel by Dylan Horrocks who, after his own amazing self-published comic Pickle was collected as the equally amazing Hicksville, spent years as a writer in the Vertigo/DC trenches.

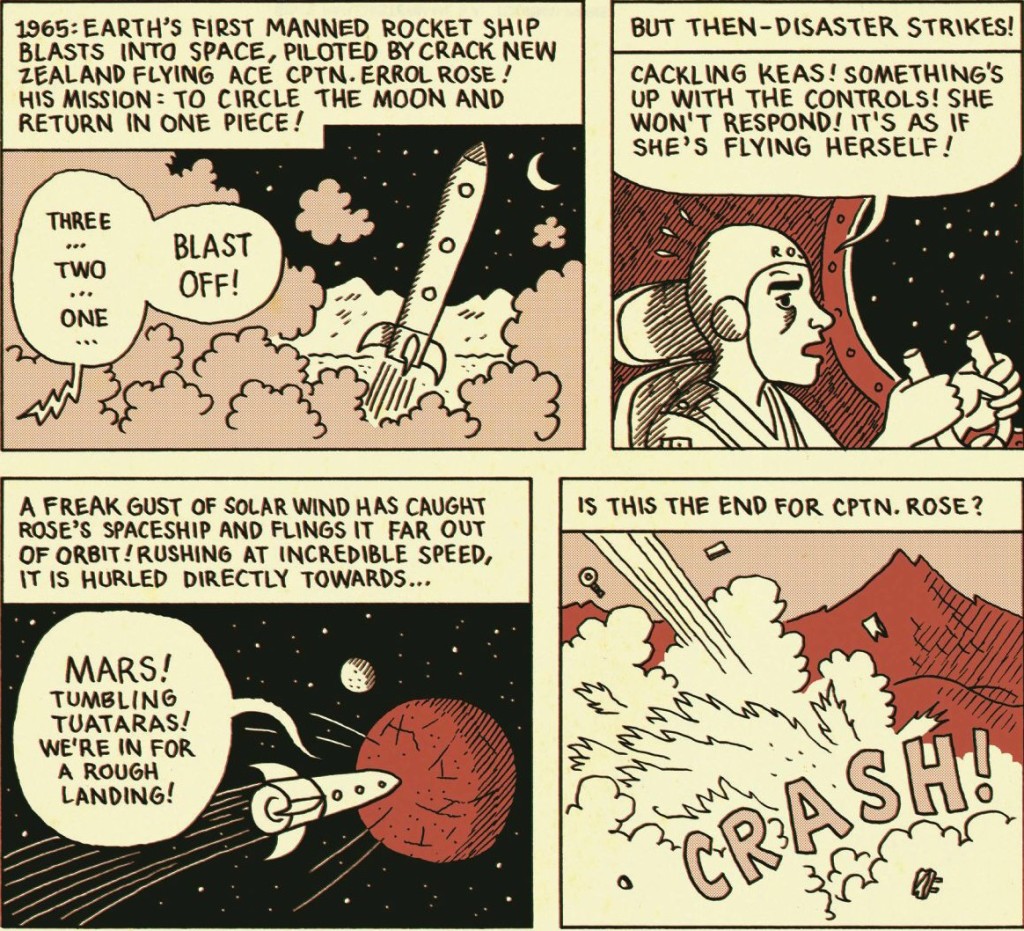

I found the opening of SZatMP, which I read back when it was published by Drawn and Quarterly as issues #1 and 2 of Atlas, pretty electrifying stuff. In it, Zabel, a thinly-veiled version of Horrocks, toils away as a work-for-hire writer on marginal superheroine, Lady Night, finding it harder and harder to meet even the low bar of hackwork. Unsure if, as his wife puts it, he’s depressed because he can’t work, or if he’s unable to work because he’s depressed, Zabel leaps at the chance to change things up and speak at a conference on “Literature in the 21st Century” at Canterbury University in New Zealand. There, he meets Alice Brown, web cartoonist, who introduces him to the work of obscure New Zealand cartoonist, Evan Rice, called The King of Mars. It’s at this point the plot takes a delightfully screwy twist and soon Zabel is plunging from comic to comic, Hickville‘s wonderful library of imaginary comics explored from the inside out.

And this is where I feel like a bit of a dick because, as delightful as SZatMP becomes, an inspiring romp that re-inspires Sam (and the reader) about the possibility of comics, I’ve read it twice and feel that it does so only by dodging the pretty thorny thematic issues it brings up at the beginning and throughout the book. Is Sam depressed because he can’t work? Ultimately, the book strongly implies as such, but its solution doesn’t map particularly neatly onto the problem.

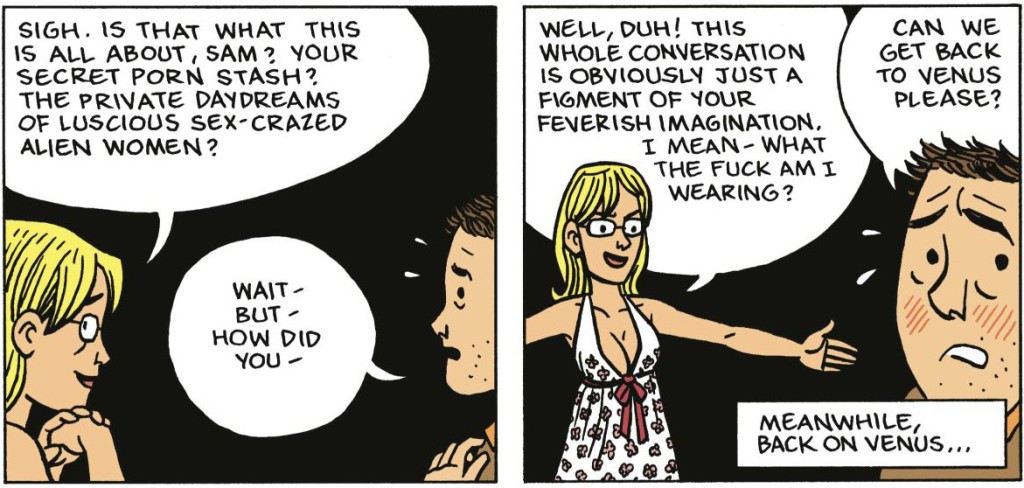

And far more problematic is how Sam (and the book) wrestles with the idea of sexual fantasy. The book opens with two epigrams, one by Yeats–“In dreams begins responsibility”–and one by Nina Hartley–“desire has no morality.” And again and again in SZatMP, we see worlds created where sexuality is either the text or subtext where Sam is tempted to partake but does not. That in itself is fine–in fact, the scene where we see what Sam is supposed to do followed by Sam not doing it (but fantasizing about it later) is lovely and human and funny and moving.

But again and again, the book suggests these fantasies are morally wrong. “There is a dark side to fantasy, Sam Zabel,” says the original, non-sexy, non-violent Lady Night. “Not all dreams are dreams of liberation, pleasure or joy. There are fantasies of purification, destruction, hatred, revenge.” Zabel and his companions repeatedly encounter situations where women are oppressed–sometimes unknowingly, sometimes very knowingly–by the fantasies of male creators.

And that’s pretty much where it’s left to lie. Although Sam’s final actions–his handling of the eponymous magic pen–is a better solution to the problem, at no point does the rhetoric step beyond the idea of “fantasizing responsibly,” as if anyone’s id has ever been satisfied that way, as if ids don’t work the exact opposite of that. Rather than looking down a possibly more diquieting path–that Sam is blocked and depressed because he doesn’t know how to handle fantasies he knows are repellent–Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen retreats into the palliative of education and metafiction, such that all those Venusian aerola are insightful, not incitement. And so although it’s sincere, the book itself is, at its core, ironic: it can’t allow itself to feel what it’s feeling.

And this probably doesn’t need to be said–or at least has been said by people smarter and better than me–but the problem with the comics industry is not the corrosiveness of male fantasy: it’s that the industry is almost completely comprised of male fantasies, that those fantasies are presented to everyone of every gender (and of very nearly every age) as if they are universal, and that the gatekeepers of the industry refuse to let in other views, other genders, to present alternative fantasies to build, at the very least, alternative audiences. (And as long as I’m shooting for context, let’s point out that gatekeeping is also created by the mechanisms of a direct marketplace that financially rewards retailers for an unwillingness to move beyond the status quo).

Maybe I’ve been boondoggled by stats and studies that I want to believe, but sexually explicit and extremely violent material has never been easier to get in my culture and yet sexual violence and violent crime has gone down. (Hell, if I remember correctly, the incidence of teen sex has gone down.) It just feels different because the acts of violence can be so much more lethal in America’s gun-enslaved culture, and because the majority of the culture is unwilling to tell a young male underclass to grow up, in no small part because there’s no place in our ultra-capitalistic world for that many grown-ups. There are no jobs for them because the money is disappearing into the stratospheres of the rich, and we’d rather all those angry young men perpetrated their violence on women than starting a class war.

Whatever the case, I did quite enjoy Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen–it’s hard for me to argue when the solution to inspiration is “read a lot of different comics,” especially in a week where I’m reviewing two manga titles, a graphic novel by a New Zealand cartoonist, and a color reprint of a British comic from 1975–but ultimately, the only magic found therein end ups being stage magic, the art of misdirection, where we must be distracted in order to be satisfied.

Hookjaw #1: Also thanks to the Sequential sale, I paid ninety-nine cents for thirteen color pages of a 1975 comic about a great white shark that eats the just and the unjust alike.

It is barely anything like a responsible fantasy, and I enjoyed it immensely. If it comes around again at $0.99, I highly recommend you pick it up!

Hook Jaw: a perfect EC Comics machine. All he does is swim, eat, and dispense a vicious sort of rough justice.

He is the best.

But how does he measure up against SHAKO?

Very, very favorably! SHAKO is loopier, HOOKJAW is darker: but they’re both hilarious and brutal stories about a force of nature tearing through the just and the unjust alike. If you like one, the chances of you liking the other are very, very good.