There is, I think, a New Teen Titans issue where the framing device is a narrator asking “What do you do after the day after you’ve saved the world?” or something similar over and over again. As cloying as it seemed at the time, it did get over the idea of anti-climax involved in coming down from such a high, and the question (or something similar) was in my head over and over as I read the solo Captain Britain stories that followed Alan Moore’s run.

Don’t get me wrong; in many ways, I prefer much of the Jamie Delano and Alan Davis-written episodes to the Moore run, because it’s not as endlessly dour and grim; there are even happy moments in there, every now and then! But it’s also a run that feels as if it’s lost and wandering around in search of a reason to exist and a story to tell, as well as one where subplots are set up and then forgotten about for months before being rushed to a conclusion needlessly. (The return of police chief Dai Thomas, who’s figured out Captain Britain’s secret identity, literally disappears between the first and final issues of the second Captain Britain series, released thirteen months apart, and its resolution is essentially, “I figured out your secret identity.” “Oh. Okay, then.”) In other words, it’s a bit of a mess.

It’s also amazingly, breathtakingly problematic in its attitude towards Betsy Braddock, Brian’s sister who would later go on to become Psylocke, the X-Men‘s favorite fetishized Asian warrior. In this period, her entire purpose was to be fridged for Captain Britain to feel bad about. That’s not as much of a joke as I’d wish; after being traumatized by her psychic powers during the Moore run, she goes on to be sexually abused — and forced to kill an alternate world version of her brother as a result — and then, after proving that she wasn’t as good a superhero as her brother, to have her eyes gouged out by a villain for the sole purpose of convincing Brian Braddock that only he has the balls to be Captain Britain after all. Those are the only major developments for her character, and in both cases, the story ignores the impact these events have on her in favor of showing us how upset Captain Britain would be, if he felt emotion. Keep that upper lip stiff, Brian.

(But there are, honestly, some good stories during the post-Moore, pre-Excalibur period: Davis having Cap visit a family to tell them that their son is dead, only to be surprised by their sad good humor is lovely; similarly, seeing Meggan come into her own, especially when she faces Baba Yaga, is surprisingly nicely done. It’s just that the good stuff is surrounded by a disturbing misogyny and aimlessness.)

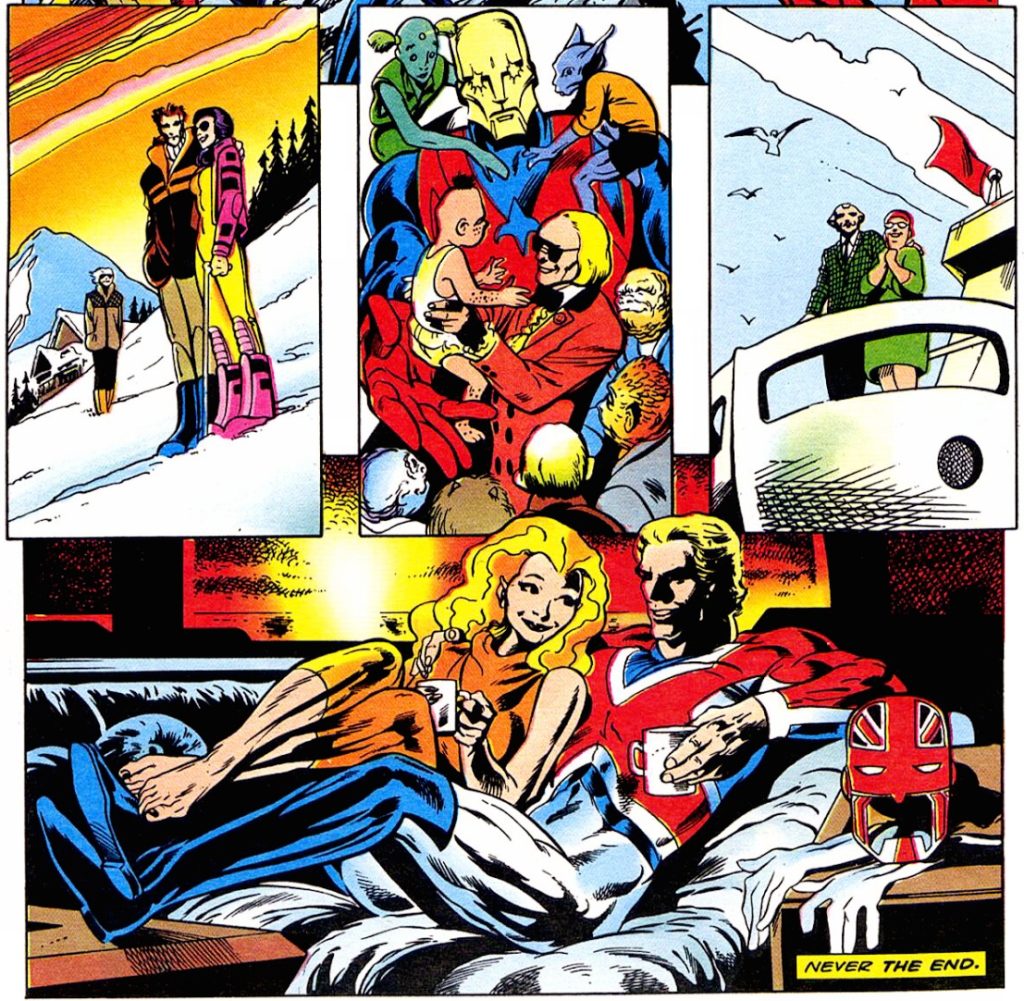

Whereas Davis’ art felt overshadowed by Moore’s story in his first few years on the character, he’s more in his element visually afterwards — there’s more room for the smaller, more subtle acting that he excels at in these stories, and even the melodrama comes in a more enjoyable, quieter package that feels more appropriate for what he can do. His style is continuing to evolve, if in a slower, more understated manner than it was during the Alan Moore era, and it allows for him to play with scale, humor and pacing in ways that are charming and perfectly set up the antics that Chris Claremont will offer him in Excalibur.

As an end to his career as a solo character — he’d go on to anchor Excalibur for close to a decade, before disappearing into obscurity before returning in Uncanny X-Men, New Excalibur and Captain Britain and M-13, as well as Secret Avengers and then more obscurity — the Delano/Davis period of Captain Britain is a bittersweet farewell. It’s uneven and directionless enough to suggest that, honestly, maybe he just doesn’t have enough to him to work as a solo character on an ongoing basis — that the Alan Moore/Alan Davis run was a fluke fueled by youth and arrogance and the desire to have an ongoing superhero job for both creators.

It’s a shame, because there is still something there, I think. I don’t know what it is, or how you’d twist and turn it until it appealed to enough people, but the idea of being the only real superhero for an entire country in a world where America is filled with them — and, on top of that, to have an inferiority complex born of class inequality and fear, and to have an origin that came from you being a pacifist who didn’t want to fight in the first place? There are all manner of elements there to use for the right creator — and, with a past that includes Claremont and Moore and Davis and Delano, there are plenty of toys and characters to rehabilitate and use if you wanted them. For anyone who wanted to pitch an All-New, All-Different Captain Britain, there’s more than enough material. All it takes is someone who cares enough.

I mean, it worked for Alan Moore, at least.

The “what do you do…” line sounded familiar but as a Legion of Super-Heroes story, not New Teen Titans, and a quick check led me to LSH 296, “What Do You Do The Day After Doomsday?”. So it’s kind of like mistaking a Blue Oyster Cult song for Deep Purple, or Bronski Beat for Blancmange – you can understand why they blur together.. (Though, to be fair, there was an early Titans issue – number 8 – called “A Day In the Lives” which followed a similar theme.)