Previously on Drokk!: The world of Judge Dredd began with the stories collected in Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 1, an uneven collection that introduced the basics but didn’t seem to know what to do with the character beyond that — which led to Dread being promoted to being Moon Sheriff for a few months within the first year of the strip. Where would things go after that? It turns out, to Hell and back. (Well, the West Coast, which some East Coasters would consider Hell.)

0:00:00-0:02:44: We return and begin again, with an introduction, a reference to Jan Michael Vincent that sees me reference this obituary from the New York Times. We’re covering Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 2 this episode, which itself contains the Dredd strips from 2000 AD prog 61-115. There’s a lot to deal with.

0:02:45-0:18:29: Before we dive into the stories themselves, Jeff references this amazing comment on the last episode from Voord 99, which we then riff off for a few minutes, including the thought that Dredd isn’t actually a strip about a future America, but a strip about American media and the stories America tells about itself; I also share the connection I share with Dredd co-creator John Wagner, and the newspaper story that made me feel better about my hometown.

0:18:30-0:33:48: We attempt to talk about the first of the two massive storylines contained in Vol. 2, but quickly get sidetracked into a conversation about the differences between Pat Mills’ and John Wagner’s Dredd, and the lengths to which Mills goes to remove Dredd from his natural environment in order to get the character to work for him.

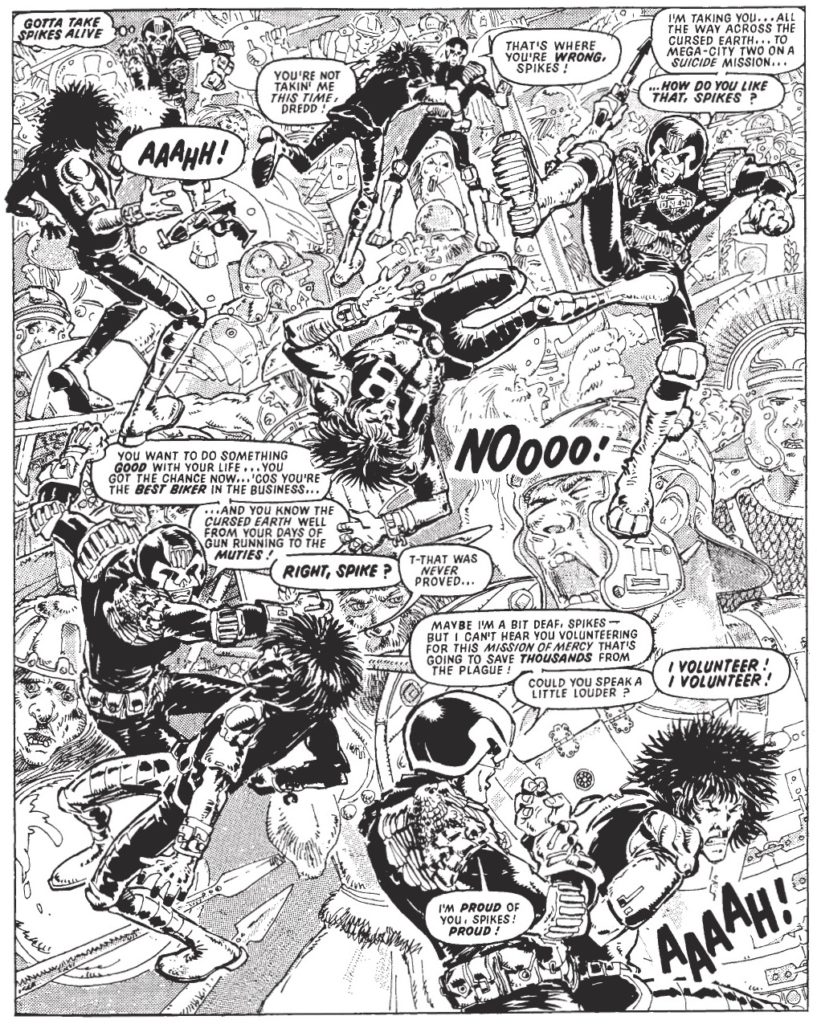

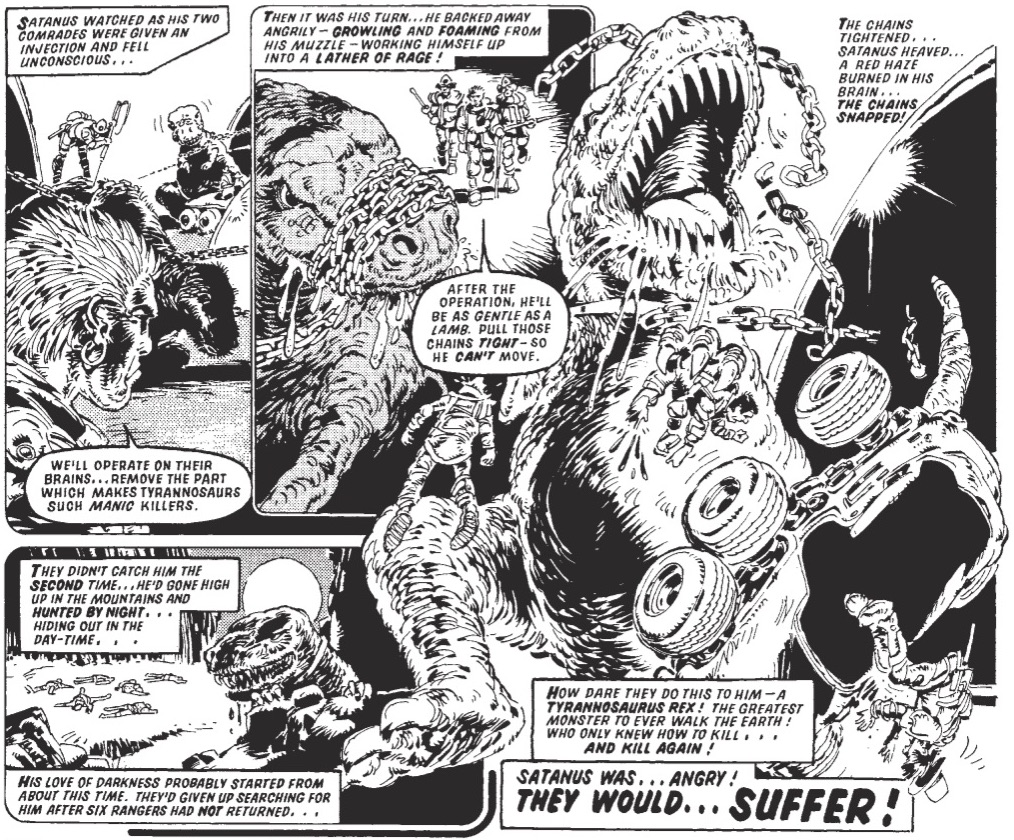

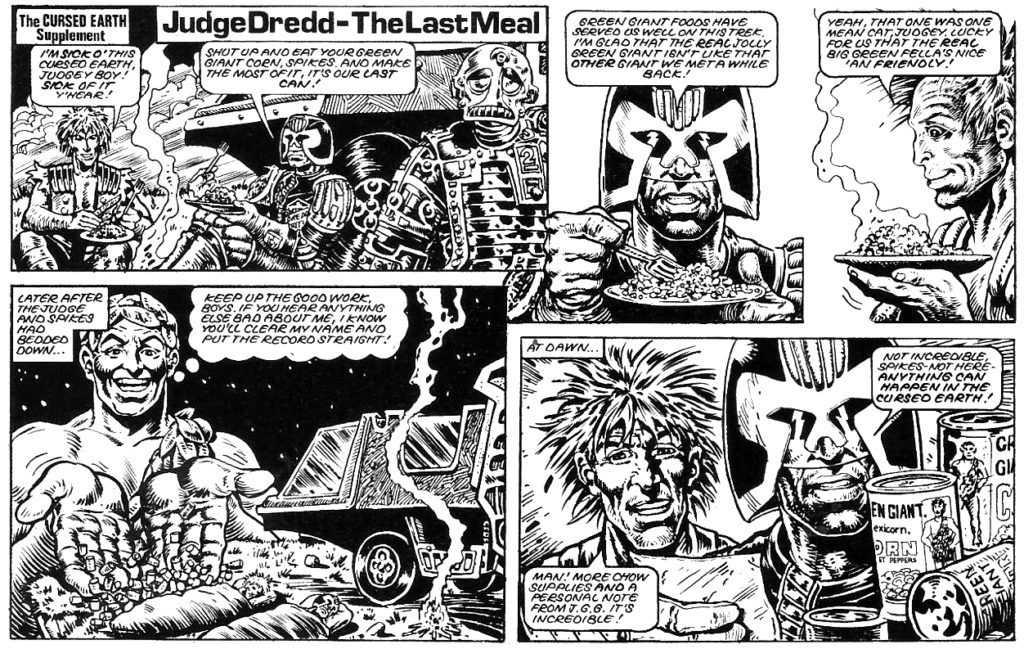

0:33:49-1:26:15: When we actually get to “The Cursed Earth” — which runs 25 parts, although four episodes are missing in the Case Files for reasons we cover; we also talk about those episodes — it emerges that both of us have a fair amount of reservations about it, not least of which the fact that it’s less a story than a framework for a bunch of different stories, and one that neither makes sense per se, nor pays off in the end. (It is, instead, Chekhov’s Gun, but only if that gun fails to fire twice.) That’s not to say there’s not a lot to enjoy about it, including the role of the movie Damnation Alley as an inspiration, the strength of two of the “censored” episodes, the fact that Pat Mills seemingly invented Jurassic Park 12 years before the original novel was released (something that Mills himself denies, as Jeff gets into), and just how lurid and pulpy the whole thing is. Also discussed: The totemic nature of Dredd’s preferred mode of transportation, the story’s two main supporting characters, Spikes Harvey Rotten and Tweak (with Jeff schooling me on why my dislike for the latter is doing a disservice to both him and Pat Mills), and just how underwhelming the finale is, not to mention the possible reasons why that might be the case. Oh, and we also reference the in-canon “apology” strip that appeared after one of the controversial now-“censored” episodes, which is reproduced below for those who are curious:

1:26:16-1:37:26: The suggestion that “The Cursed Earth” was truncated leads to a brief discussion about whether or not the underwhelming nature of the story’s climax was the result of editorial mandate or exhaustion on the creators’ parts. Was Mills just done with Dredd by the time he reached the end, or did editors want to wrap it up in order to let John Wagner take over? (I also tease something that we’ll get to in two episodes’ time, when we finally reach “The Judge Child Quest,” because I am bad at foreshadowing, apparently.)

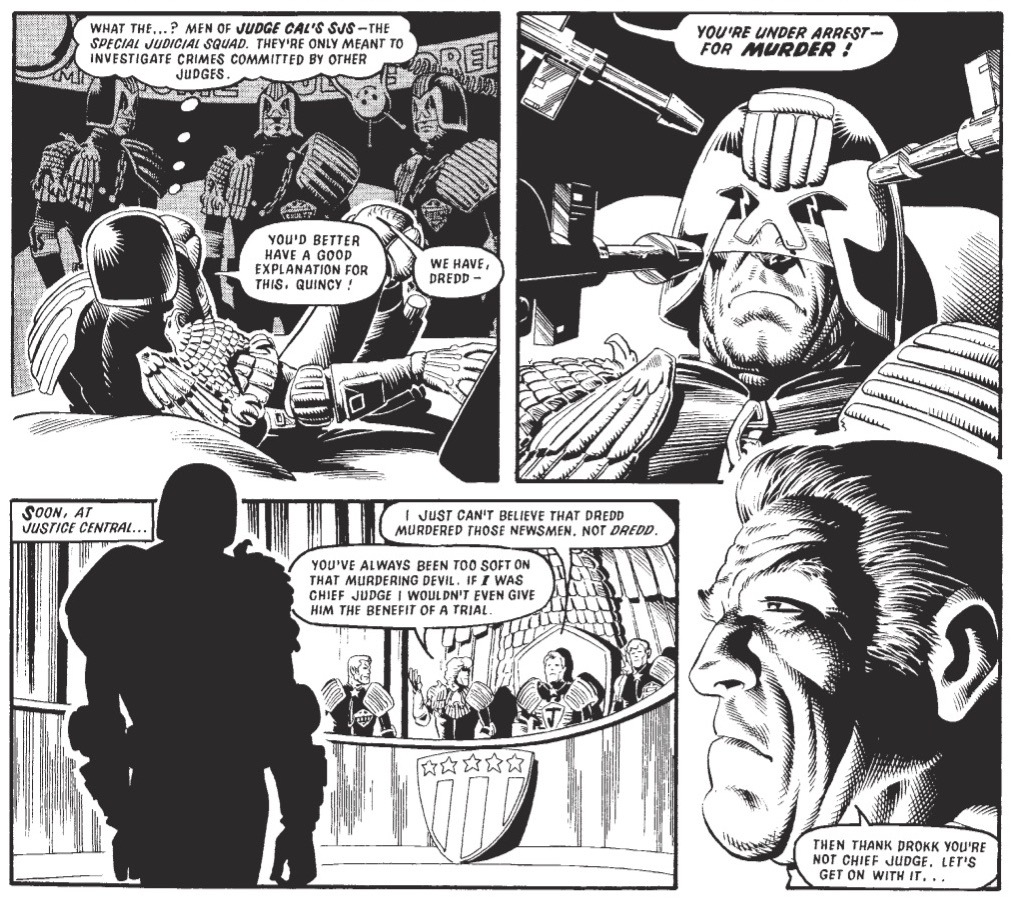

1:37:27-1:44:20: From the ridiculous to the sublime, we move from “The Cursed Earth” into the extended Judge Cal storyline, which sees John Wagner take over as the primary writer on the strip — a position he has essentially held ever since; he’s doing it under the “John Howard” pseudonym with this story, though — and basically give everything from Judge Dredd to Mega-City One itself a quiet reboot. It begins with a three-part prologue that doubles as a fake-out, however, and Jeff and I talk about the red herring, the wonderful Silver Age quality of the three-parter, and also how racist Wagner’s Judge Giant looks forty years later. (No, really; why should a Judge be talking jive?)

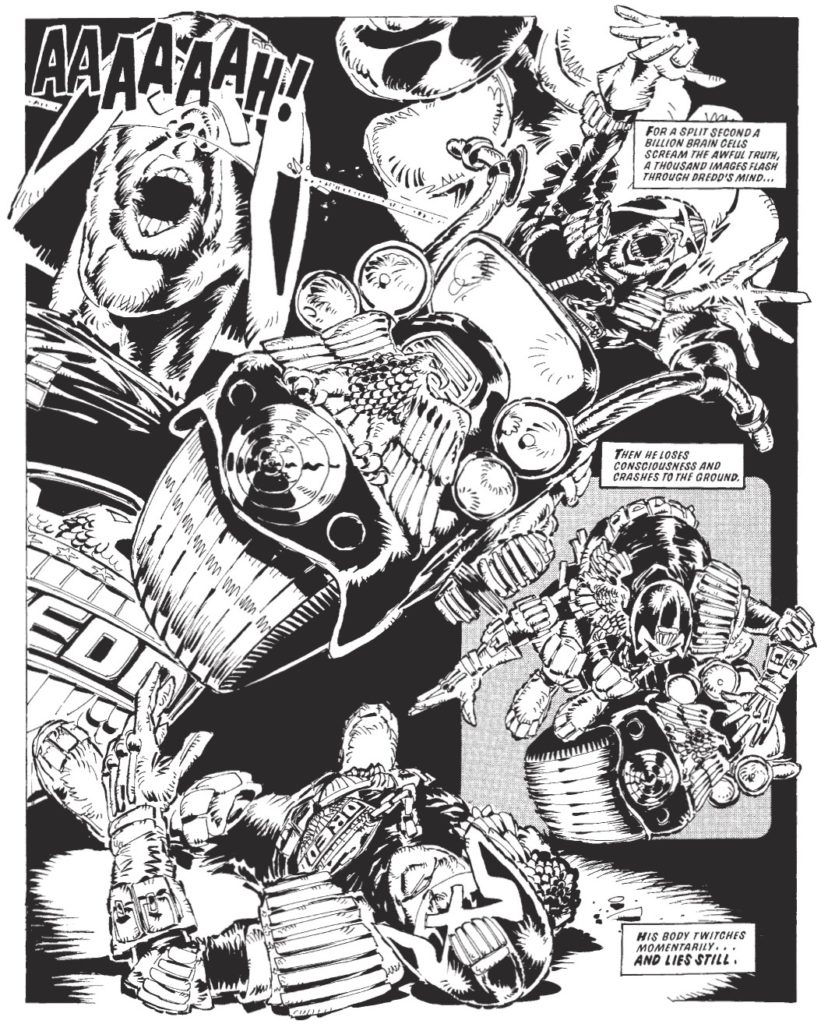

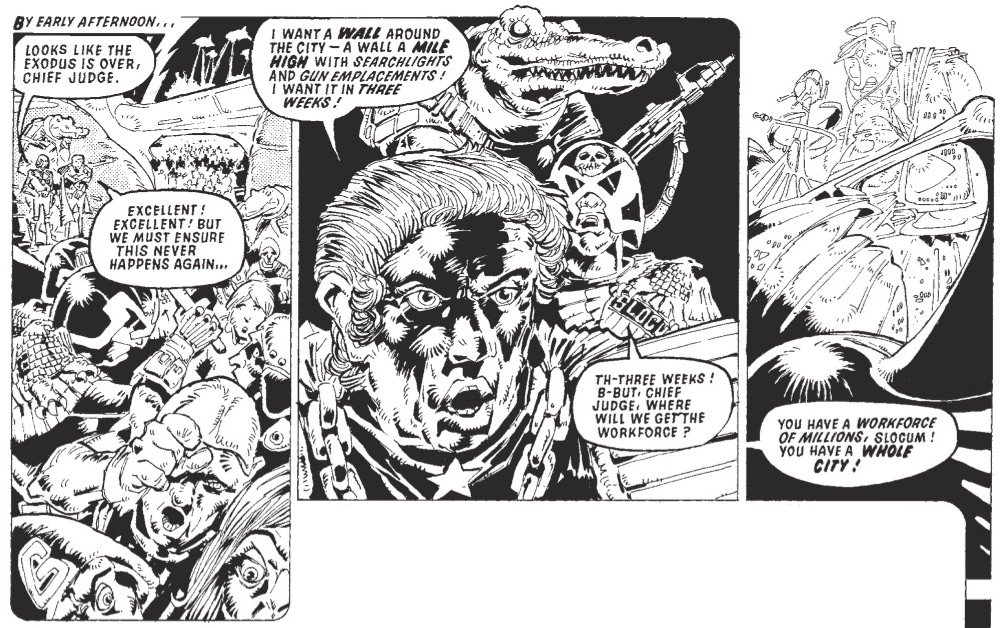

1:44:21-2:29:45: “The Day The Law Died” transforms the Dredd strip on multiple levels, taking it into new areas of satire and tonally transforming it from sci-fi pulp into something more operatic and, honestly, darker. It starts with an unforgiving first episode and just doesn’t stop until things finally wrap up. We discuss all kinds of things, not least of which Wagner’s mastery over the serial format (and the 2000 AD episode length); what the reader expects from the Judges as a narrative device, and how easily we believe that they can be used for evil; the origins of the term “Scrotnig”; Judge Cal being the anti-Dredd, being as self-indulgent as Dredd is self-controlled; the Donald Trump parallels that utterly derailed us; Fergee and why Jeff and I don’t get the joke; the arrival to the strip of Ron Smith and the visual evolution of the character and the strip across the two years it had existed by this point, and much, much more. Suffice to say, we really loved this storyline.

2:29:46-2:38:37: As we try to wrap things up relatively quickly — we had, after all, been going on for more than two hours by this point, we reach what might be Jeff’s first-ever Dredd story (featuring a reference to Whispering Bob Harris of all people), and take the very shortest trip into the question of whether or not John Wagner is sympathetic to the Judges as a concept. I mean, surely not, but yet…!

2:38:38-end: Finally, we discuss overall impressions of this volume, whether or not we’d recommend it as a good starting point to a Dredd newcomer — the phrase “kind of like huffing a lot of paint and then reading a bunch of Jack Kirby’s comics” might be used — talk about our favorite episodes in the book and then get to bringing everything to a timely close with mentions of our Tumblr, Instagram, Twitter and Patreon. We’ll be back in a month with Vol 3 of Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files; until then, thank you for listening and reading, and never forget: Easy the Ferg.

For those looking for a direct download link: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp2.mp3

The most remarkable Cal-as-Trump moment is the bit at the funeral of Judge Fish, where he is at first convinced that there must be a huge crowd present despite the fact that the streets are empty, and then gets furious when he is told there is not.

….aaaand I got to the end of the episode, and you mentioned that bit. Teach me to comment before finishing.

I had the Matchbox Land Raider also, back in the ‘80s, no idea why, I grew up in the US, not Britain. Always loved it, played with a lot as a kid. I only got into Dredd and 2000 AD a few years ago (I think when Jeff mentioned the digital subscription). When I finally got around to the Cursed Earth in due course, my mind was absolutely blown by the Killdozer.

I’m interested in Graeme’s comment that “aliens don’t work in Dredd”. I’m not sure exactly what he means, but it touches on what I feel is a core contradiction in the setting. For context, I’m reading along with the podcast and don’t know how the universe is going to unfold in future volumes when I say this. My question is:

“Is the universe of Judge Dredd fundamentally a world where the human race is on the upswing or the downswing?”

On the one hand, you’ve got the classic tropes of a post-apocalyptic dystopia. The “Cursed Earth” is a nuclear-ravaged desert surrounding the lone outpost of civilization that is Mega-City One. It’s dirty and dangerous and if you follow the tropes I just sort of assume that the machinery of civilization would be breaking down, that every year fewer people know how to repair the infrastructure, resources grow scarcer, etc. There is nowhere to go…

Except the colony on the Moon. Or apparently the interstellar rocketships exploring the entire galaxy and plundering it for resources (as per Tweak’s story). So there’s nowhere for the citizens of MegaCity One to go… except the rest of the universe. Rest of the Earth? Are there parts of the Earth that weren’t blown up by nukes?

Are the Judges a desperate attempt to keep a collapsing world from falling apart, or is there some greater human civilization colonizing the galaxy without judges and Mega-City One is basically for the losers in the “bad part” of the Earth?

Really interested to see which way it goes.

The Cursed Earth was when I started reading 2000AD on a regular basis. It was McMahon’s art that just became irresistible. I suspect Pat Mills’s watered-down-heroic=Dredd sort of held my hand leading me into the world, but it is pretty irritating now. The number of times Spikes reminds Dredd of what the mission is, only to be ignored as Dredd risks everything for another bout of knight-errantry is breath taking. If anyone else had survived the journey, Cal would have had legitimate reasons to punish Dredd’s lack of judgement. Fortunately for comics, Dredd’s poor decision making meant no other survivors.

Your discussion of authority and discipline in Dredd brought up uncomfortable feelings of my own to the surface. Some years ago, when people started talking about ‘failed states’ it was like a crystallisation of my fears from childhood. I grew up in Northern Ireland and dearly did not want order to collapse. There’s something about having family members leant on by a group of armed men that left me really not wanting a weak state to fully fall apart. These fears are at odds with some of my ideals. Which makes reading Dredd fascinating.

Oh and Ron Smith! I rank them, McMahon, Smith, Bolland. It’s telling though, that I don’t know of any artists trying to emulate Smith’s amazing illustrations.

It kind of goes both ways. That’s always been an inconsistency that’s bothered me too.

Well, I’m obviously extremely flattered (but, wow, do I use a lot of parentheses), I was also fascinated to hear about how Graeme McMillan’s engagement with Dredd was affected by actually being from Greenock.

– If Graeme McMillan can call The Day the Law Died great literature, I’ll go so far as to risk this: I think this is the most interesting that Dredd has been as political thought.

People call Dredd a fascist. John Wagner calls Dredd a fascist. And there are obviously a lot of ways in which that’s true. But there is at least one important way in which Dredd doesn’t map onto historical fascism well at all.

Fascism is notoriously difficult to define — it’s more of a constellation of historically associated tendencies than a coherent system, and you can pick or choose what you regard as essential . I had a discussion with someone on a different forum who (in what I regarded as a very American way to look at politics) thought that if it something didn’t explicitly state that corporatist economic policy was a central goal, you couldn’t call it fascism.

I imagine David Morris would point out that I’m doing something very similar when (having grown up as I did in Ireland), I think something essential to fascism is that it’s nationalist. And Dredd isn’t a nationalist, ideologically — it’s a humanizing touch, a place where the facade breaks down for a moment, when he tells Chopper he’ll let him race and tells him to win “for Mega-City One.” That’s Dredd displaying a sense of devotion to his group that he’s *not* supposed to do,

But which fascists thought you should. Fascism had a very different attitude to the law than Dredd: law needed to be subordinated to a higher “good,” the nation, and extra-legal action was not only acceptable, it was desirable if it served the nation. There was also a worship of action about fascism, an impatience with the limits of process and legal procedures, an admiration of the bold, decisive figure who sweeps these aside and acts.

(Mills’ Dredd is obviously a bit like this. As our hosts point out, his law is a higher law. But that’s fairly obviously, especially in light of the Brother James aspect — Mills modelled aspects of his Dredd on a horrifically violently abusive priest that he had as a teacher* — Catholic natural law, and so self-consciously internationalist and universal in character.)

To give a concrete example of a place where Dredd is not much of a fascist, there’s the comic sequence where he comes back from Luna-City One and won’t act to stop crimes, because he hasn’t been sworn in yet. I think that’s revealing of the sort of totalitarian that Dredd is: he’s not about subordinating process and law to any higher end — process and law are the end in themselves.

In other words, Dredd is about taking liberal democracy and stripping away liberalism and democracy, so what you’re left with is nothing but bureaucratic procedural regularity. Which is a great source of dark comedy in that classic absurdist Monty Python vein.

Judge Cal is really well-suited to bring all that out. “Living law” is a real thing that was associated with Roman emperors and was passed down to discussions of later European monarchy. (It’s distantly part of the intellectual background to the power of the US President to grant pardons.) I’d be interested to know if Wagner knew that, or it was just a brilliant stroke of intuition.

The “living law” idea is closely related to that liberal-democratic obsession with procedural regularity, but from the point of its monarchist opponents. It involved the observation that law is necessarily about establishing general rules, whose inflexibility must always come up against situations, given the complexity of human life, in which they produce unjust results. In contrast, a human being can take into account the full spectrum of moral considerations in a way that a crude general rule never could. So the monarch is “living law,” of equal and superior authority to the written law and able to grant exceptions to it, , etc.

This is where Cal’s absurdity, his arbitrary decision-making, is so powerful, because it reveals the absurdity that is central to Dredd’s comic side: at the end of the day, Dredd’s law isn’t really that much less insane than Cal’s insane decisions, because it’s not *for* anything. It’s just sort of there, So Dredd himself is really no less insane than Cal.

– On the other hand, I don’t think it can be denied that there are unpleasant aspects of a mincing gay stereotype to Cal. Those are also characteristically part of hostile stereotypes of upper-class and upper-middle class southern English people from the perspective of people who are (variously) not upper or upper-middle class, southern English, or English. In that second context, the association with ancient Rome is important, given the significance of classics as a marker of elite education in Britain.

That’s also the best I can do with Fergee: he’s the anti-Cal, uncivilized and brutish, but by that token not effete. Although he’s also curiously American, with his baseball cap and baseball bat. There’s no reason to locate him next to the Ohio River, and no reason to have the Ohio in this at all (the Hudson is far more likely to be known to a British audience) except that John Wagner was originaly from Pennsylvania (although I haven’t been able to find out where in Pennsylvania).

So there might be something in there about Fergee as a representative of the crass, brutish US displacing the British Empire from the center of history, and with it the imperial ruling class?

*Mills’s Catholicism is generally really interesting to me, but it’s marginal to Dredd, so I won’t go on about it here.

A couple of quick notes: this is more about nationalism than it might appear. Patrick Eamon Mills is a product of the Irish diaspora in England (sic). Mills has an interesting and complicated relationship with his Englishness and his Irishness, but it’s really more a conversation to have about Sláine and Nemesis. But note the Roman soldiers fighting stereotypical barbarians in the background of the panel above, with the Romans presumably there as prototypes of Dredd, and the barbarians as prototypes of Spikes Harvey Rotten,

I’ll also note that Mills’s school was simultaneously sheer hell on an absolutely horrifying scale, rife with both sexual and physical abuse (Mills collects stories from fellow former pupils on his blog), and a place that produced remarkable and successful people: among the people with whom Mills was at school are Chris Mullins, the MP and novelist, John McDonnell, the current Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Brian Eno.

I gave a bit more thought to Fergee, and it occurred to me that Jeff Lester, with his interest in psychological and especially Jungian interpretations, is probably better equipped than I am to do something with this hairy brutish figure, nothing but irrational impulse, who is literally buried in an underworld beside a river.

One thing I’ll add to Fergee as the anti-Cal is how scatological Fergee is: sitting on a toilet, beside a “Big Smelly” river, constantly surrounded by flies like a piece of dung. So there’s maybe something in there about our own discomfort with our bodies and bodily processes. Meanwhile, the immaculately groomed and effeminate Cal is also associated with plumbing, but in his case it’s a bathtub.

I don’t get the joke with Fergee either, but, as drawn by McMahon in his first appearance, he looks to me to be modeled on Alfred E. Neuman, a famous American optimist. After a few weeks, and other artists, the resemblance is pretty much gone.

https://www.madmagazine.com/sites/default/files/imce/2015/10-OCT/MAD-Magazine-Alfred-E-Neuman-New-York-Mets_562f9c57e399c5.01325419.jpg

I always thought Mills’ comic scripts were so incredibly broad because he’s writing for the kids – the smart 8-year-olds, rather than the smart 12-year-olds that Wagner was targeting. He’s made no secret of the fact that he thinks 2000ad’s biggest mistake was growing with its audience and leaving the kids behind, and that’s the audience he’s always been after, who aren’t worried about plot holes, and just want dinosaurs and vampires and Jimmy Carter’s teeth.

That doesn’t really explain why even his serious adult-aimed stuff like Third Word War could also be broader than Broadway. Maybe he’s always just a kids author.

And while Judge Giant’s jive dialogue is truly indefensible, I thought it was Cool As Shit when I was one of those 8-year-olds, and made him one of my absolute favourite characters in the whole thing – the bit where he rescues the injured Dredd was enormously thrilling.

I think there’s an element of writing consciously for children in Mills. There’s definitely a tension between Mills the pragmatic writer who focuses on what sells, and Mills the person who is this close to being a colossal tankie. He tends to deal with this tension by claiming that he writes subversively for the valorized “ordinary person,” without really grappling with the objection that being the first Mills might involve him in perpetuating all those systems of privilege and oppression that the second Mills hates so much. Then again, I think Mills would probably dismiss that as a “North London” way of talking.

But I don’t think you can attribute his tendency to write in a very broad way solely to the first Mills, because, as you point out, it doesn’t get less extreme when he’s writing for older audiences, and, in fact, it’s present in the very good/bad either/or way that Mills talks about politics in his own voice.

One thing that I think is quite important here is that Mills seems to have been quite devout as a child. He was an altar boy, and he has recently implied that he was intending to become a priest when he was in his early teens. Bertrand Russell has an interesting essay on the difference between Catholic and Protestant sceptics in which he observes that Protestants tend to be able to leave their churches as an intellectual move without any great emotional dissonance, because they can still align themselves with Protestantism going all the way back to Luther as a tradition of freethinking — atheism as Protestantism that takes the next step. For Catholics, though, leaving Holy Mother Church is, well, like leaving your mother: Catholics who leave the church tend to have strong anticlerical feelings of hostility and resentment.

In Mills’ case, the Church and his actual mother are intertwined: his mother appears to have been a classic devout Irish woman of the older type for whom the Church could do no wrong. (Although it was an aunt who blamed a young boy for leading a priest astray, which might sound absurd, but in the context of midcentury Irish culture is entirely plausible.)

Basically, I think the boy can leave the Church, but that doesn’t take the Church out of the boy. Pat Mills’s world is a world in which there is the good and the bad: this is the defensive, brittle, repressed world of De Valera’s Ireland made still more defensive and repressed by being a minority in England. Mills has just changed what he puts in the “good” box and the “bad” box.

I rather hope I never meet Pat Mills, because I don’t think I could resist asking him offensively personal questions. How personal? “Mr, Mills, Dave Maudling is in some respects based on yourself, and you talk a lot about how you like to draw on reality in general. So when you write that his English father used to get drunk and call his Irish mother his ‘white chimpanzee,’ is that something that your father used to do to your mother?”

Although it was an aunt who blamed a young boy for leading a priest astray, which might sound absurd, but in the context of midcentury Irish culture is entirely plausible.

It dawned on me that I did not phrase this very well. Just to be clear, I mean that it is entirely plausible that Pat Mills’s aunt might have thought and said that, not that it’s plausible that the boy really did lead the priest astray.

I was interested y’all’s brief comments about the evolution and maturation of Dredd, and had a moment of synchronicity with it since I’ve been reading a bunch of Warhammer 40K fiction lately. There’s a Dan Abnett story from the early ’00s where Inquisitor Gregor Eisenhorn, who’s been busily fighting big conspiracies involving black magic, demons, and such, is called in to look into clearly cult-related murders in a crapsack neighborhood of a crapsack world. (Spoilers for “Missing in Action” ensue.)

Mid-rise was a dismal, wretched place of neglect and poverty. A tarry resin of pollution coated every surface, and acid rain poured down unremittingly. Raw-engined traffic crawled nose to tail down the poorly lit streets, and the very stone of the buildings seemed to be rotting. The smoggy darkness of mid-rise had a red, firelit quality, the backwash of the flares from giant gas processors. It reminded me of picture-slate engravings of the Inferno.

He learns that lots of people in the neighborhood, including the accumulating corpses, belonged to a regiment that was part of a crusade against chaos horrors a sector over twenty-five years earlier. And it turns out…there is no cult, no demon, nothing but trauma.

‘So, these men… and women…’ Midas mused. ‘Soldiers, been through hell. Fighting the corruption… your idea is they brought it back here with them? Some taint? You think they were infected by the touch of the warp on Surealis and have been ritually killing as a way of worship back here ever since?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I think they’re still fighting the war.’

IT REMAINS A sad truth of the Imperium that no virtually no veteran ever comes back from fighting its wars intact. Combat alone shreds nerves and shatters bodies. But the horrors of the warp, and of foul xenos forms like the tyranid, steal sanity forever, and leave veterans fearing the shadows, and the night and, sometimes, the nature of their friends and neighbours, for the rest of their lives.

The guards of the Ninth Sameter Infantry had come home thirteen years before, broke by a savage war against mankind’s arch-enemy and, through their scars and their fear, brought their war back with them.

The arbites mounted raids at once on the addresses of all the veterans on the list, those that could be traced, those that were still alive. It appeared that skin cancer had taken over two hundred of them in the years since their repatriation. Surealis had claimed them as surely as if they had fallen there in combat.

He tries to save the survivors, and can’t.

We could hear the singing. A couple of dozen voices voicing up the Battle Hymn of the Golden Throne.

I led my companions forward, hunched low. Through the crazed windows of an inner door we looked through into the main hall. Twenty-three dishevelled veterans in ragged clothes were knelt down in ranks on the filthy floor, their heads bowed to the rusty Imperial eagle hanging on the wall as they sang. There was a yellow chalk cross on the floor under the aquila. Each veteran had a backpack or rucksack and a weapon by their feet.

My heart ached. This was how it had gone over two decades before, when they came to the service, young and fresh and eager. Before the war. Before the horror.

‘Let me try… try to give them a chance,’ I said.

‘Gregor!’ Midas hissed.

‘Let me try, for their sake. Cover me.’

I slipped into the back of the hall, my gun lowered at my side, and joined in the verse.

One by one, the voices died away and bowed heads turned sideways to look at me. Down the aisle, at the chalk cross of the altar, Lund, Traves and a bearded man I didn’t know stood gazing at me.

In the absence of other voices, I finished the hymn.

‘It’s over,’ I said. ‘The war is over and you have all done your duty. Above and beyond the call.’

Silence.

‘I am Inquisitor Eisenhorn. I’m here to relieve you. The careful war against the blight of Chaos that you have waged through Urbitane in secret is now over. The Inquisition is here to take over. You can stand down.’

But one of them overreacts in a way that makes the local open fire, and none of them survive.

It felt to me a lot like the best stories you’d find in 2000AD these days, and sooo far from where it all started.

So it was interesting to have the same thought swirling around from different origins.

I haven’t seen the movie but in the Zelazny novel they are driving across America to deliver a vaccine and they can’t fly because of constant storms. It’s been ages but I think the storms had rocks in them sand blasted everything over a certain altitude.

The Deputy marshal in the Luna arc was from Texas-City so the idea is already there if not fleshed out.

In Warhammer 40k there is a tank called Landraider that kind of looks like the Killdozer part, but then there are other Dredd influences in 40k (and probably other 2000AD properties that I’m less familiar with).

Apologies if you already knew this, but didn’t have time to explain it, but the comment about Cal getting the trains running on time is a reference to a myth about another historical dictator of Italian origin- Benito Mussolini: https://www.quora.com/Whats-the-significance-of-the-phrase-Mussolini-made-the-trains-run-on-time

I think that’s undoubtedly the main point of reference. But it also reflects the situation in early 1979 (TDTLD concluded in April 1979), because these were comics conceived in the context of the Winter of Discontent — the perception that Britain was a country that had fundamentally ceased to function, which at the time did raise fears and worries (which may seem overstated in hindsight, but were real at the time), that British democracy might be in trouble and that only some sort of authoritarianism could enable basic things to get done.

One thing that I’d be fascinated to know is how long the lead time on these stories typically was, and how long before a story was published it was written. The fact that The Day The Law Died ended in April 1979 means that it was the last important Dredd story to appear before the May 1979 General Election — somewhere near the beginning of the next Case Files is the first Judge Dredd story to be written in Thatcher’s Britain.