Previously on Drokk!: Two years’ worth of Judge Dredd strips have passed, but things are only now starting to congeal when it comes to working out just who the title character is for both creators and readers, it seems, with John Wagner taking over the strip essentially full-time as writer with the length (and wonderful) “The Day The Law Died” cycle of stories. With Wagner installed permanently as the man in charge of Mega-City One, what lies ahead?

0:00:00-0:01:54: We speed through an introduction, and let the people know that we’re covering Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 3 this time around, which covers material from 2000 AD Progs 116 through 154, from 1979 through 1980. Really, we’re pretty expedient and impatient this time.

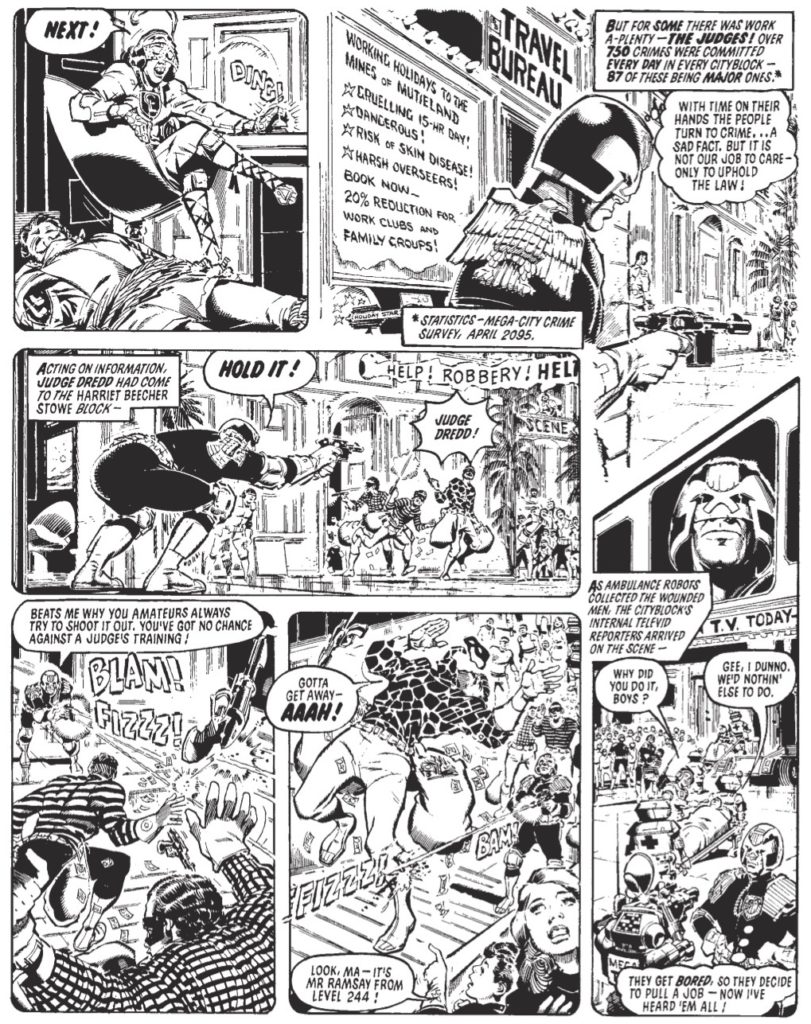

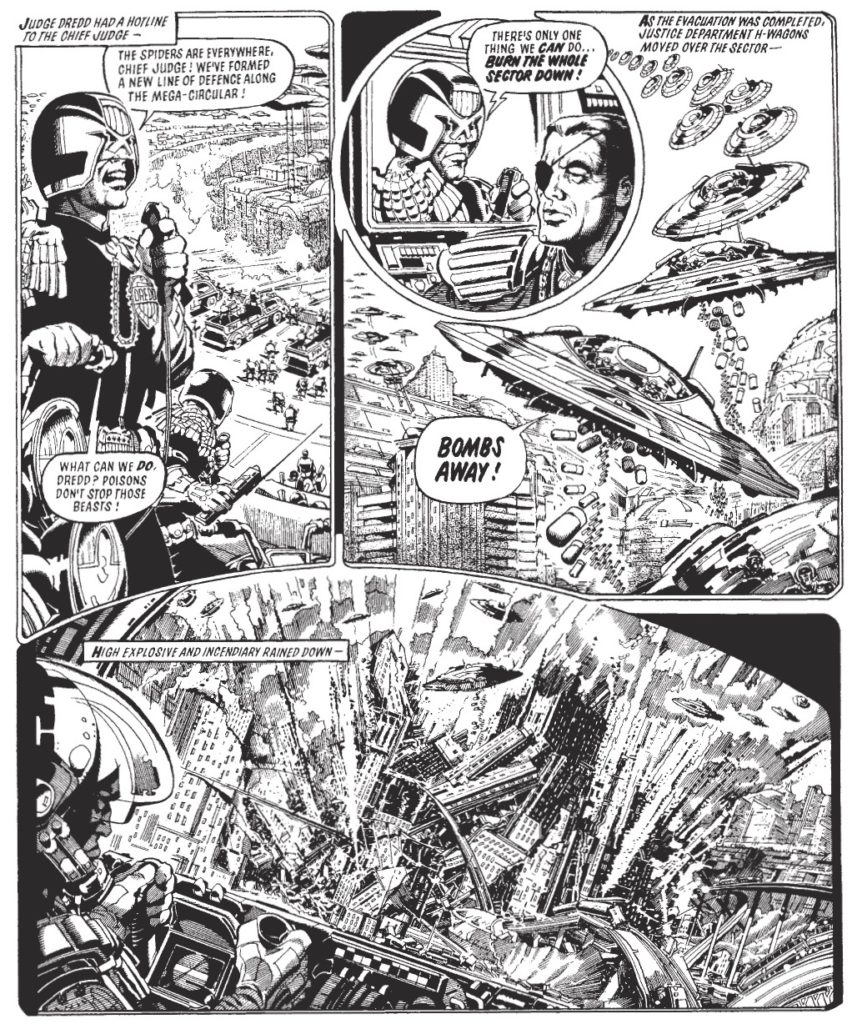

0:01:55-0:17:46: Although Vol. 3 is a collection of short stories — the longest continued narrative is just five episodes — there’s a throughline to be found, and we talk about what we both think is the most obvious candidate: That this is the volume where Mega-City One is solidified as a location, and what that means. (Spoilers: Jeff makes the apt point that the best on-screen depiction of Mega-City One is arguably Springfield in the monorail episode of The Simpsons.) Also, mention of the “Vienna” episode of the strip, which starts the book off, gets us talking about Dredd as an emotional being, and what that means to the strip as a whole, with references to romance comics and Gil Kane in the offing. Does John Wagner have a better idea of what Mega-City One is than he does of who and what Dredd is by this point?

0:17:47-0:26:31: A brief discussion of what it must have been like to be reading these stories when they appeared — not only for the variety and quality of Wagner’s writing, but also weekly art from the likes of Ron Smith, Brian Bolland and Mike McMahon — brings us back to the idea of Dredd as the natural successor to Will Eisner’s The Spirit, and the ways in which the two strips are similar. (And the ways in which they’re dissimilar, as well.)

0:26:32-0:30:31: Mention of Jeff’s love of Ron Smith leads us to a very short digression about the visual evolution of the Dredd strip through the three years to date, and from the Ezquerra/McMahon aesthetic to the more refined Bolland/Ron Smith look, and what that means as a whole.

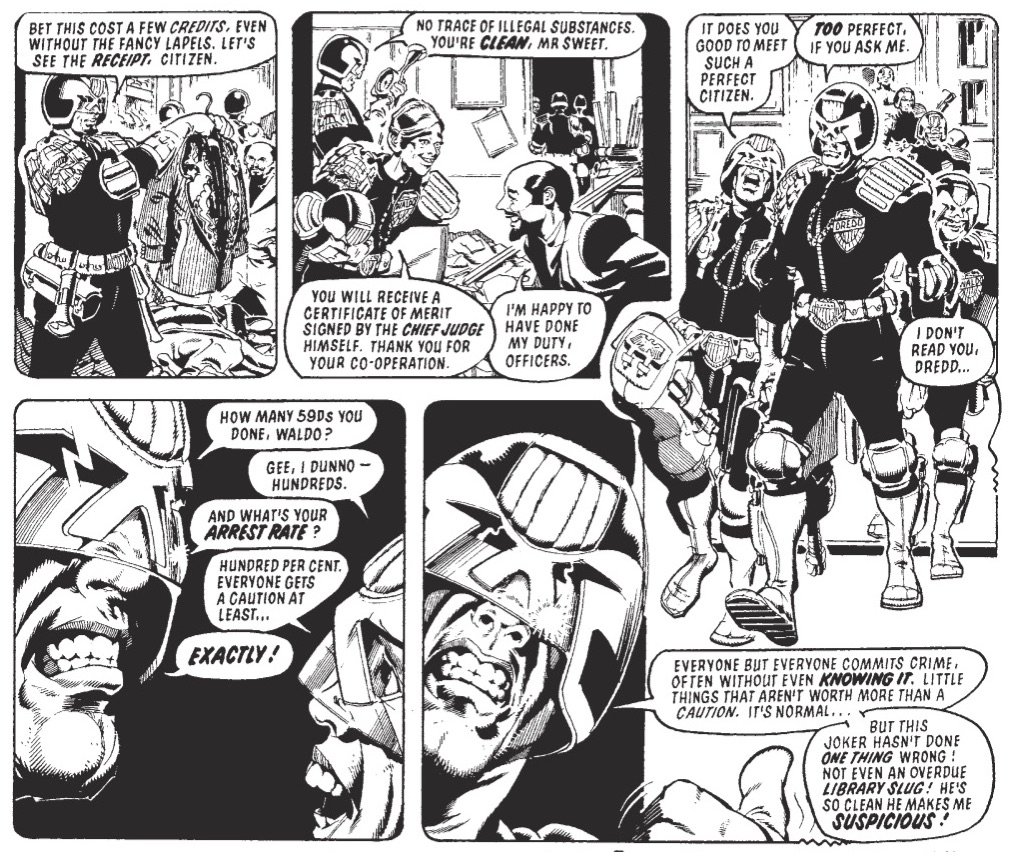

0:30:32-0:38:17: And then we’re back to talking about the writing — namely, the status quo of Mega-City One, and how the Judges interact with the citizens. We talk about two foundational lines of dialogue that set the stage for everything that happens afterwards, and quite how stacked the odds are against any MC-1 citizen for not having a bad experience with the Judges at some point in their lives. The future, it seems, isn’t just unkind to regular people: It wants to try and break them.

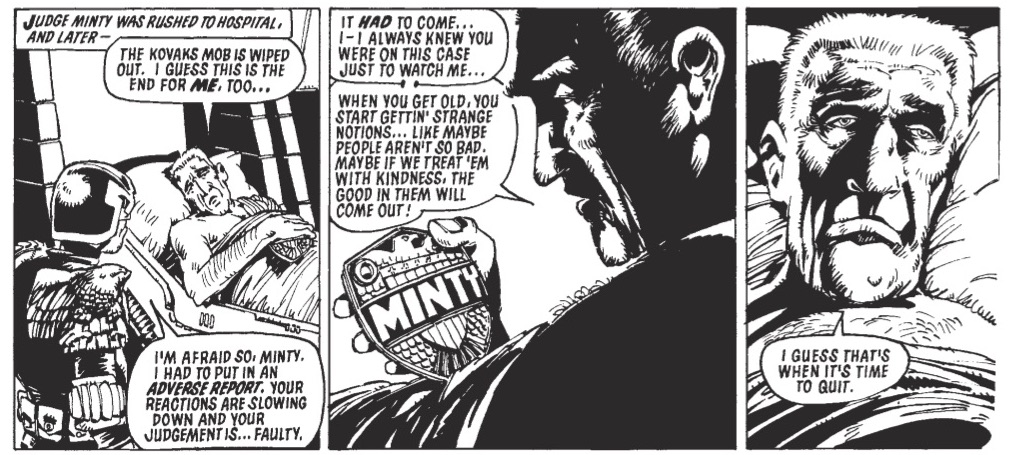

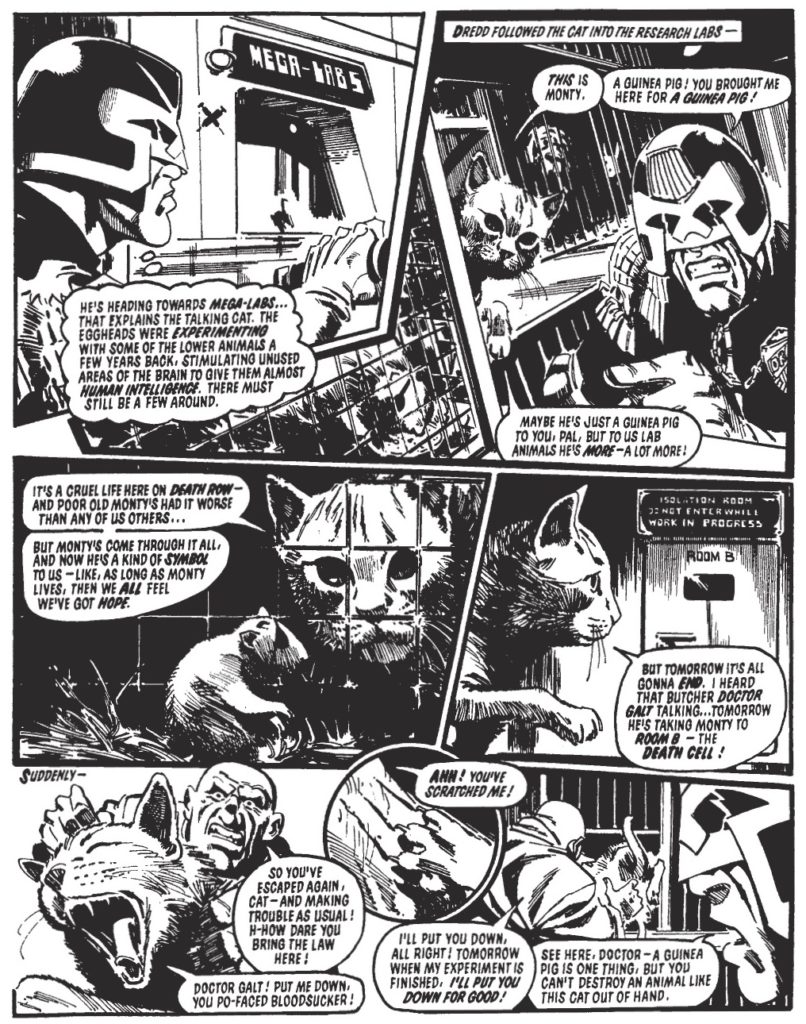

0:38:18-0:53:19: This leads on to a theory I have about this volume offering an unexpected reason for Dredd to be the series’ protagonist — that he’s an aberration as a Judge because he repeatedly is shown to embrace characteristics that are seen as being reason enough to make Judges retire, but is nonetheless successful as a Judge despite (or because of) that. In discussing this, we end up talking about a story in which Dredd deals with animal experimentation, in what Jeff describes as the perfect blend of “radical politics and silver age DC storytelling tropes.” Oh, and John Cooper’s cat drawings, which are uncannily good.

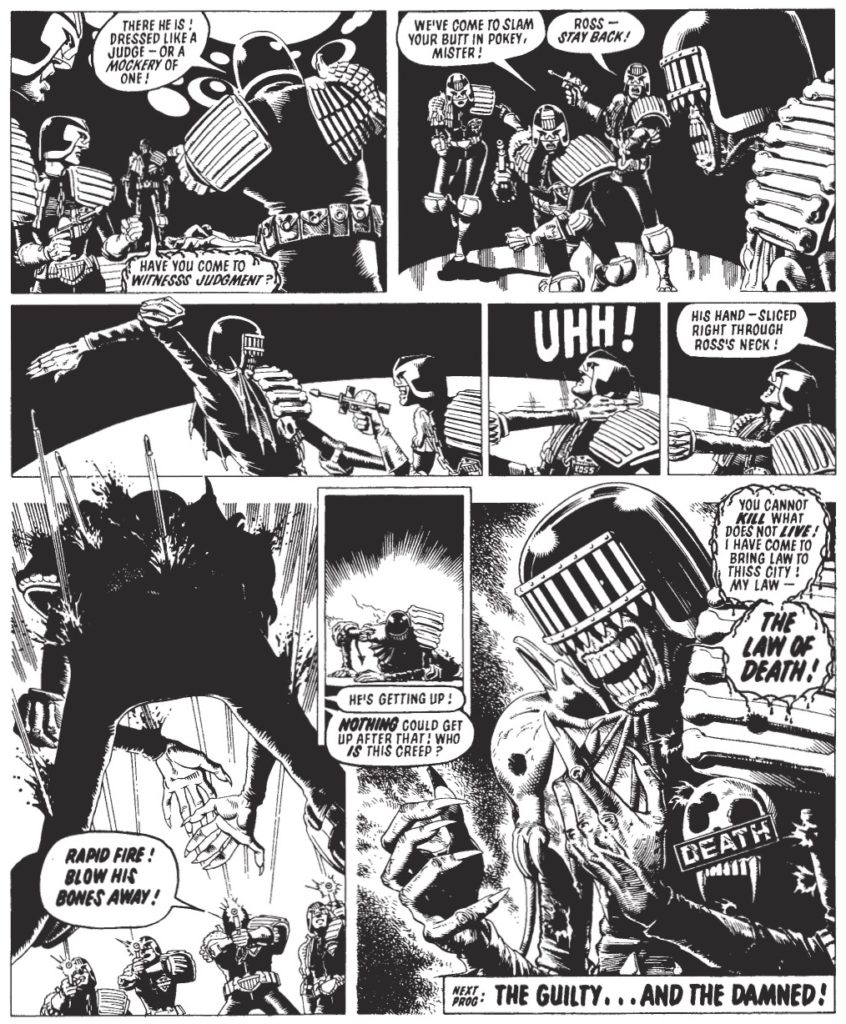

0:53:20-1:06:34: With Jeff having talked about the animal experimentation story being one of his favorites in this volume, we run down the other contenders, which includes an early example of GoFundMe, the first appearance of Judge Death and more — which turns into a discussion about the sense of both continuity and consistency of location that Wagner manages to create around Mega-City One and Judge Dredd the strip in this volume, as well as the tonal variety consistently employed by the series at this point.

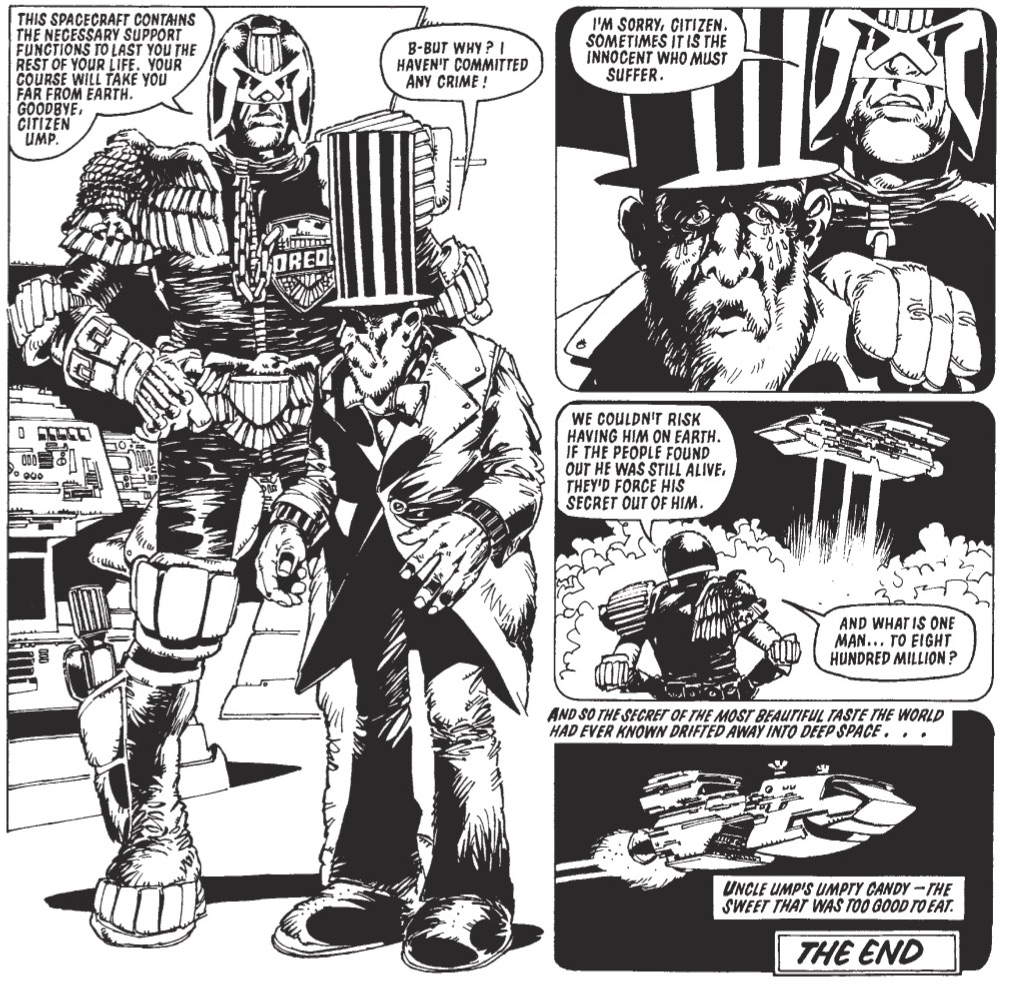

1:06:35-1:17:08: We move onto some of my favorite stories, and also return to the idea that the citizens of Mega-City One are doomed to failure simply by living in the time and place that they do, with Jeff dropping a reference to a 1976 novel about man’s inhumanity to… well, everything, really, called Dr. Rat by William Kotzwinkle. Was this a reference on Wagner? Who can tell, but it doubtlessly was less grim as the Umpty Candy story, which both Jeff and I found ourselves fascinated by, not least of all because of how Mr. Ump was dressed, and the moral of the story…

1:17:09-1:29:14: From the sublime to the shit, as we talk about Pat Mills’ sole contribution to the volume, the less-than-good “Blood of Satanus” three-parter; this leads into some chat about the fact that we both felt like Mills was more present in the book than he actually was, and what the legacy of Pat Mills on Dredd actually might be. Come for that, stay for the mention of Henry Ford the Horse, of course, of course.

1:29:15-1:38:37: This volume turned out to be John Wagner’s moment to shine as a solo writer — which will happen again, of course, throughout Dredd history — and I wonder as to his method in writing such a long game-type of a comic strip. We talk about the unique position Wagner is in with Dredd, and also how it allows for a strange sense of realism unavailable in almost every other comic property.

1:38:38-end: Coming in hot as we try to wrap things up, Jeff and I both talk about whether or not we’d recommend this volume to newcomers, tease what’s happening in the next episode of Drokk! and do the traditional mention of our Tumblr, Twitter and Instagram accounts, not to mention the Patron that’s responsible for this whole thing. It’s a lot, I know, but Grud thanks you for reading and listening as ever.

And here’s the direct link for the audio, for those who need it: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp3.mp3

Vienna comes back in prog 1300, so she is not ignored or forgotten, they just waited for her to grow up.

Thought it was obvious that Judge Sweeney in The Great Muldoon was a woman, but I guess it can be less clear in BW (I read the “Maximum Colour Edition”).

In general I think this short story collection was a more pleasant read then the long stories. Even if Judge Cal was a lot better the Cursed Earth it still got a bit boring. I’ve read Judge Child before (25 years ago or something) and don’t have fond memories, so next volume could be rough. :)

Yeah – she shows up in Day Of Chaos as well in an interlude where Dredd makes sure to keep tabs on her amidst all the, er, chaos.

I just found this blog post about the 1982 Judge Dredd board game, which is an interesting curio with nice art: https://www.belloflostsouls.net/2018/05/retro-judge-dredd-board-game-from-a-very-familiar-workshop.html

That Wagner pulls elements from Bruce Forsythe and Hughie Green to forge Johnny Teardrop’s voice is another example of the UK drawing on how it’s embraced US culture, while claiming it’s a critique. I can confirm to Graeme that even in my late teens reading these stories week by week was amazing. I have clear memories of reading progs at my girlfriends flat off Hawkhill in Dundee and passing them on to her.

I thought the comparison of Ron Smith to Vince Colletta in any way was unfortunate. There are plenty of professionals who maintained a large workload to achieve the income they wanted, Kirby for instance. I haven’t seen anyone following Smith in the way I notice artists imitating McMahon and Bolland. I suspect people might prefer not to invite the comparison with Smith’s command of scale, space, machines and architecture.

I was loving his work in the previous volume, but with this one Ron Smith became my favorite Dredd artist for all the reasons you stated. Bolland has some great figures, but the dynamism always f Smith’s layouts and backgrounds really keeps me engaged. Some of his facial expressions were straight up Wally Wood level.

Great episode guys, especially the focus on the art. The Ron Smith legend about his production method is that, according to him, he knew what his time was worth. So he’d calculate out how much he was getting paid per assignment, break down how much per hour and per page that was according to what he thought his time was worth, then set a timer while he was working. When the timer went off, he’d move on to the next page. So yeah, depending on how much he was getting paid, he would either crank out the pages or take his time.

Regarding Vienna, yeah, she doesn’t make any sense with the timeline. Wagner apparently immediately realized his mistake, and decided to ignore her until he could figure out a way to resolve that issue and come up with a story that actually needed her. This took twenty years, but eventually in the late 90s/early 00s, Wagner figured out a way to have Rico father a kid while in prison, at which point Vienna comes back into the strip. That’s all collected in the Brothers of the Blood trade, which also introduces Rico Jr., and is the point where Wagner really starts playing into the “Dredd is really, really old, and out of step with the rest of Justice Department” approach.

Hilariously, Wagner also returned to the kid Walter said Dredd adopted around the same time, only this time Wagner reveals Dredd immediately abandoned the kid after that issue and his life went to shit as a result.

The thing I find fascinating about this year of Dredd is that it ends up being an unknowingly transient year. Alan Grant joins Wagner as his writing partner at the start of Vol. 4, making this the only point where Wagner has solo control of the strip. I wonder whether Grant helped push Wagner away from the need to humanize Dredd the way he does in Vol. 3. Grant is on record as saying he preferred writing Dredd as more of a force of nature than a character with an interior life. This very much fits in with Grants solo writing career, where his characters are much more stand in for the ideas of the plot than people who have any interiority. I could see a case to be made that Dredd with the kids is Wagner trying to figure out how to make Dredd more than just the lawman, and Grant either pushing him past that or giving him permission to leave that behind.

Your suggestion about Grant’s influence makes a lot of sense.

It’s an obvious piece of supporting evidence that one of the reasons why Wagner and Grant stopped writing together as their default was a disagreement about how Oz should end — Grant wanted Dredd to kill Chopper by shooting him in the back. Which would obviously have given a definite ironic coloration to the earlier moment when Dredd lets him race, which is a “Dredd has a heart after all” moment not unlike the ones on which our hosts were commenting.

I do think, however, that one can put dark-comedy moments like Dredd proving that he has a heart of gold by sentencing someone to hard labor or giving Edwin the Confessor exactly what he wants in a slightly different category from things like Vienna. They’re part of how Mega-City One is this bizarre topsy-turvy world, and what “kindness” means is insane. They don’t really take the edge off. While on the other hand, visiting the little boy is normal everyday kindness of a type that we recognize and does take the edge off by presenting Dredd as a normal boys-adventure hero.

Scattered thoughts:-

– It was really great to hear our hosts enthuse at the end. There’s such a sense of this horrible slogging weight lifted off them as compared to the later stretch of the Baxter Building.

– One thing about Wagner’s “long game” that I think one should add is that in part it’s because his imagination was so fertile. He kept coming up with new stuff, and so it could be a long time before things came back. Contrast Lee/Kirby, since I mentioned the Baxter building – if anything worked in early FF, Lee and Kirby made it a point to bring it back almost immediately. And this is another side of how impressive Wagner’s economy of storytelling is, because he’s not bringing things back in a context in which he has to come up with new story ideas at an absolutely frenetic, at times weekly, pace.

– Yay, Charlton Heston Block! I’ve been waiting for this moment. For me, an absolutely essential part of Mega-City One is that everything is named after celebrities.

Early on, they’re clearly part of the American color of the setting, and aren’t used for humor and irony the way that they will be. Charlton Heston, the first one, is presumably just “generic American movie star.” There is also no obvious significance to the fact that Edwin the Confessor lives in Carlos Santana Block.

There’s a very specific moment when Wagner does two linked things. One, the name has significance. Two, the celebrities don’t have to be American. And it’s brilliant: Enid Blyton Block. Associating Enid Blyton with a story about people being horribly killed by a giant alien alligator-monster is a wonderfully pointed mission statement. It says everything that Mills would like to say about 2000AD, but does so much more efficiently than Mills ever does. (Note also the wonderful cynicism of the portrait of the Johnsons, as our hosts pointed out.)

– One thing that I think is quite important is that these stories mark the entry of someone who will be a central and defining figure for 2000AD for the next eleven years, and maybe beyond, which is obviously Margaret Thatcher.

Or does it? Was Thatcher actually Thatcher so soon after May 1979? When I initially read the story about unemployment, I couldn’t help but read it as an anti-Thatcherite statement, and as marking a shift from the way in which the Robot Wars and the Judge Cal storyline reflect different aspects of the atmosphere of pre-Thatcher Britain. Basing a story around the idea that people *want* to work, and that unemployment isn’t their fault, seemed an obvious riposte to things like Norman Tebbit’s dad getting on his bike.

But, wait, this is still 1979. The Conservatives have just won the election on the slogan “Labour isn’t working.” The link between Thatcherism and unemployment hasn’t been forged yet in the popular consciousness. So I think that the story is prescient – it’s framing unemployment in a way that’s not obvious in terms of its actual moment, but is going to seem extremely so a couple of years later.

This is in general something that I’ll be interested in looking out for as we move into the ‘80s. It relates to Dredd-as-America-in-British-culture, because one of the things about the ‘80s is that there was political convergence between America and Britain, but cultural divergence. While in America a lot of the films and TV shows that define the ‘80s (Rambo, the A-Team, etc.) are recognizably in tune with Reaganism, in Britain things that sum up the ‘80s (for me, anyway) are more likely to be oppositional: things like alternative comedy and yes, 2000AD. Put it this way, if America had had the Falklands War, there would have been dozens of movies and TV shows with Argentinian villains.

– Like our hosts, I’ve also been looking out for female judges. (The Judge Cal story is hilariously male, given the number of judges in it, sometimes in crowd shots.). It’s curious that they are so slow to appear: the Metropolitan Police had had WPCs (still called that in 1979) for sixty years.

The first definite appearance (Judge Kelly in the Chamber of Horrors story) is a bit cringe-worthy: she is there to reassure a terrified woman. The sexism gets a bit better after that, though (aside from the toxic-masculinitytastic role of Judge Harkness —the story is notable for introducing judge celibacy), especially if Parker is meant to be a woman. That female judges are not given distinctive uniforms (unlike British policewomen) is an interesting touch, which probably reflects US cop shows.

– Add to the list of things that seemed futuristic and horrific back then, and now very practical and normal: the idea that spy-in-the-sky cameras would keep us under constant surveillance.

– There’s the story about the mobster testifying, and it is, as our hosts noted, fun and enjoyable. But,umm, I hate to ask but… isn’t the whole concept of Judge Dredd that judges hand out summary judgment and that there aren’t, you know, trials for Lips to testify at?

– It’s amusing how crap Dredd is in The Blood of Satanus: he doesn’t listen to Lynsey, blames her for not leaving an address — it being far from obvious how that would have made any difference—, and then gets the burglar killed. Pat Mills’s solution to his problem of “How do I write Dredd if I have to write him in Mega-City One?” is apparently to decide that Dredd is a bit useless at his job.

Listening you guys talk about Doomsday, Heroes in crisis, year of the villain and all of that other DC nonsense I found interesting as a non DC reader, however made my brain hurt. It’s sort of put me off from modern DC, but I am going back to reading older DC since I got hoopla.

Also I can’t wait to hear you talk about Endgame, because I would like to hear some one talk about the movie without the fanservice moments, because some of scenes are my favorite, but make no sense. Whatever.