Previously on Drokk!: We’re firmly in what commenter Jared so suitably termed “the Golden Rut” of Dredd, where everything is technically going well with the strip in both its 2000 AD and Judge Dredd Megazine incarnations, and yet, it’s feeling increasingly difficult to say anything about it. If only, say, Garth Ennis would return as writer or something…

0:00:00-0:03:51: Welcome, dear friends, to the 2001-2002 revival that is Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 34, which reprints material from 2000 AD Progs 1250-1275, and Judge Dredd Megazine Vol. 4 #1-6. Jeff tries to pick a fight about the dates of the material, but I’m having none of it, for once. Don’t worry; I’ll have a lot of it soon enough.

0:03:52-0:24:48: We dive into things relatively quickly, talking about the 10-part “Helter Skelter,” which marked Garth Ennis’ return to Dredd after almost a decade, during which time he’s become the toast of the American comics industry, thanks to the success of Preacher. We talk about how the story relies entirely Ennis’ fanboyishness about Dredd, which overwhelms the skills (and detachment) he’s displaying elsewhere in his career at this time, the many ways in which it fails as a piece of writing and whether that’s down to laziness or Ennis’ unwavering fanboy nature concerning Dredd, and the fact that the serial features that rarest of things: disappointing Carlos Ezquerra art. There is, at least, an explanation for that, which we also get into.

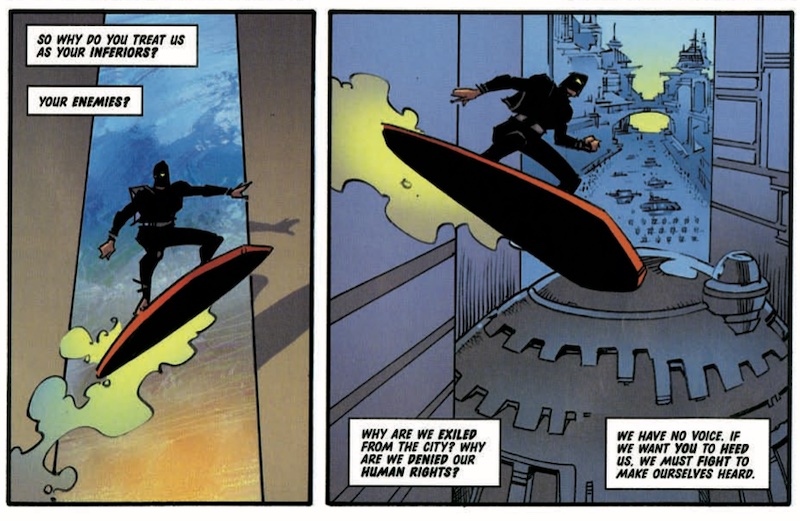

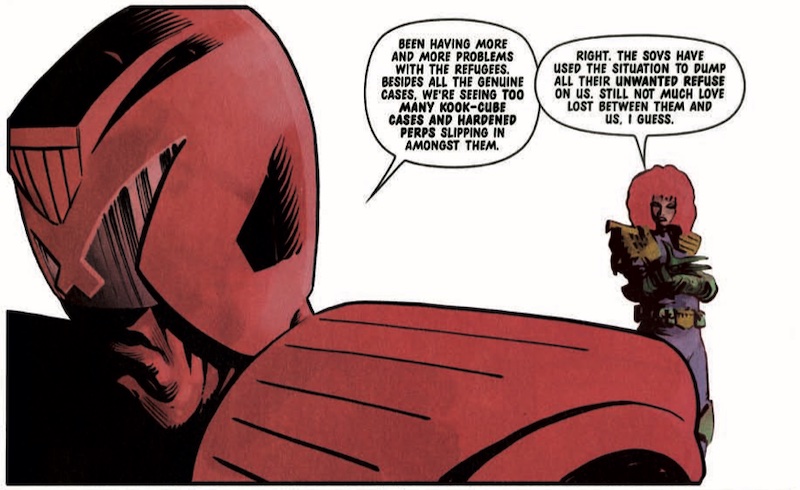

0:24:49-0:42:29: I attempt to segue from “Helter Skelter” into better stories but get in my own way by mentioning the contributions made by writer Alan Grant to this volume, which include the shockingly bad stoner comedy “Leaves of Grass” — guess what? Even when stoned, Judge Dredd is the law! — which Jeff, nonetheless, feels has a lot more potential than I do. (He also liked “Helter Skelter,” so perhaps this is the episode where Jeff is the good cop to my bad cop, for once.) (Wait, is that every episode?) I also talk about “Terrorist!” — yes, it actually has an exclamation point in the title — which comes from a well-intentioned place, but feels as if it betrays some deep-set prejudices in the minds of its creators. That gets us onto a brief discussion of whether or not it reflects a post-9/11 sensitivity, as well as whether the Robbie Morrison-written “Born Under A Bad Sign” does the same, albeit from a different direction. Also! When did The Wire start? That important question, answered!

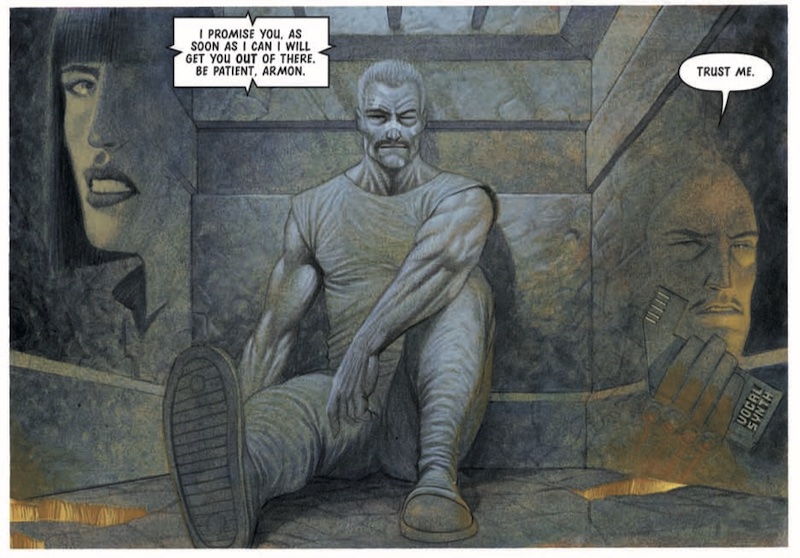

0:42:50-0:53:25: Surprisingly, we only spend 10 minutes on my favorite story in the volume, which is one that Jeff likes a lot, as well: “Bad Manners.” We discuss the ways in which it underscores the failure of the system, and succeeds at criticizing the Justice System of Dredd as a strip in a way that something like “The Runner” from last episode stumbled through. In a strip where ACAB is an unstated understanding, this is a story where the subtext pushes through to become the text.

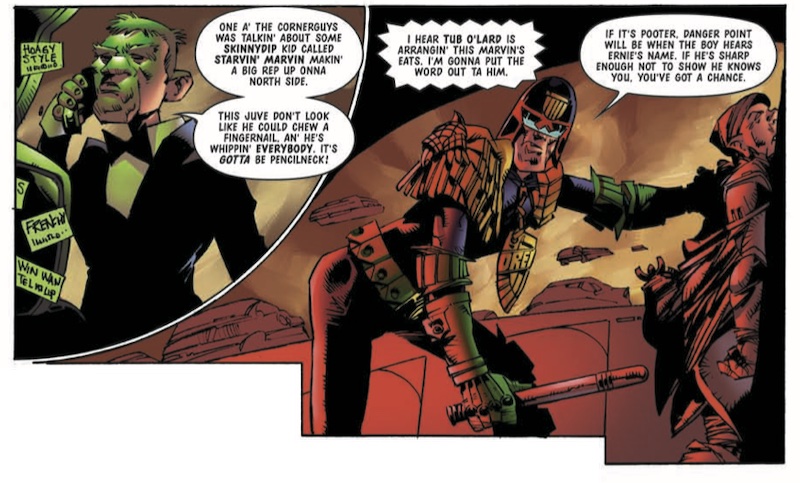

0:53:26-1:13:26: What starts as an attempt to talk about how the newcomer writers deal with Dredd in this volume — Robbie Morrison disappoints, while Gordon Rennie does surprisingly well, with a couple of his efforts reading like Wagner in places — ends up being an appreciation of what the artists are up to this volume, courtesy of singing Frazer Irving’s praises on his one-off “Asylum.” Under particular discussion are Cam Kennedy and Colin MacNeil, both of whom get the chance to shine in Wagner-written stories. Kennedy is responsible for a few stories this time around, but it’s “The Bazooka,” a Fatties story that he draws for Wagner in the Megazine that really shows off his gift for cartooning and physical comedy, while MacNeil handles “On The Chief Judge’s Service,” which is by far superior to last volume’s “The Chief Judge’s Man” in large part because of some very smart choices on MacNeil’s part. Also having their praises sung: Cliff Robinson, who Jeff compares to Chris Weston…!

1:13:27-1:22:53: We talk a little about the context surrounding his volume — 2000 AD and related titles being bought by new publisher Rebellion, and Andy Diggle taking over as editor — as well as whether we’re ending the Golden Rut this time around. Also, Jeff brings up the “bonus story” in this volume, which leads to more Cam Kennedy appreciation.

1:22:53-1:29:25: What are Jeff’s favorite stories in the book? (I’d already mentioned mine earlier, when talking about “The Bazooka.”) And is this volume Drokk or Dross? Spoilers: we both think it’s a strong Drokk, especially considering the running order of the book — the fact that “Bad Manners” is essentially the end of the book — there are another couple of shorts that follow, including a particularly disappointing Alan Grant story, but still — means that the reader is still thinking about it by the time they’ve finished, which helps considerably.

1:29:26-end: As we head towards the end of the episode, we look forward to Case Files 35 next month, and I discover that Americans apparently didn’t know what a helter skelter was, which kind of blows my mind. (We also mention the Twitter and the Patreon, because that’s what we do.) As with every single one of these, thanks for reading and listening; it’s very much appreciated.

One of the neat things about this volume was getting to ‘Slick on the Job’ and comparing it to the writing of ‘Helter Skelter.’ It amused me how close to the satire Ennis lands. Your mentioning ‘Troubled Souls’ reminded me that the first John McCrea art I saw, some time before that, was a fly-posted image of Storm stuck on a wall in the Smith field area of Belfast. I don’t remember what the purpose of the poster was, but the name stuck.

Cliff Robinson’s art has changed a lot. His pages are now so information rich. Lots of small panels with well thought out detail instead of instead of Bollandesque noodling. It does make me wonder about the process in Dredd. I’d assumed the writers produce a full script, but the artists certainly seem to have latitude with it, with varying results. Anyone know?

‘Leaves of Grass’ is poor, but it did prompt me to re-read a couple of other ‘stoned Dredd’ stories, ‘Report to the Chief Judge on the Accidental Death of a Citizen’ and ‘The Ballad of Toad McFarlane.’ I don’t think I can be objective about the story quality of either of these because Brendan McCarthy, but they did support a hunch. I think Richard Elson is inking the story differently as a nod to early McCarthy.

I think you should be able to finish the year with volume 40 if you take a month out of the regular case files and read the (probably pretty terrible) Restricted Files volume 4.

One line I want to pull out of Ennis’ Dredd story:

“A Judge is on the streets one hundred fifty hours a week. The rest is paperwork and sleep machines. There’s no pay. No property. No Personal time.”

150 hours a week? That leaves 18 hours for everything else which doesn’t seem like it would lead to the most productive/useful Judges. Also, if the Judges don’t own anything or have any money, where do Hershey (and the rest of the female judges) get their makeup from? (Maybe each sector hours has their own makeup artist?)

Thanks for the shoutout guys, glad you found the Golden Rut so useful for this episode.

One thing about this period of Dredd that I think gets lost when only looking at Dredd and not the broader 2000ad of the time, is how much Dredd must have been an island of stability at the time compared to the other serials they were putting out. Strontium Dog had never recovered from killing Johnny Alpha (really from Ezquerra walking off the title, if we’re being honest), Judge Anderson is, let’s say, still there telling stories about whatever book Alan Grant read that week, Slaine and Nemesis had become emeshed in Pat Mills’ weirder obsessions, and the only real new strips that had any kind of juice where Sinister Dexter and Nikola Dante. David Bishop went into considerable depth in Thrill Power Overload about the behind the scenes chaos he was dealing with during the back half of the 90s, both from fights with Fleetway and their marketing department to the long list of serials 2000AD put out that didn’t land, so the fact that Dredd was dependably consistent and wasn’t rocking the boat was probably a godsend at the time. Yes, it all reads fairly samey when you’re looking at the casefiles, but considering the dumpster fire Dredd was at the start of the 90s, plus the fallout from the Stallone movie, just getting the strip to the point where Dredd was not actively dragging down the rest of 2000AD was a huge accomplishment. As Graeme said, we’re now moving out of that period, but I still imagine Dave Bishop going “Oh thank Christ” every time Wagner sent in a new, no fuss script.

Not much else to say on this episode, except one anecdote. As great as his art is on Bad Manners, John Burns apparently hates drawing Dredd. He thinks the uniforms are stupid and impractical, and is much happier drawing things like Nikola Dante. So anytime he shows up for a Dredd strip, I just imagine him drawing every page through gritted teeth.

Scattered thoughts:-

– The Bazooka is close to the pure Platonic ideal of a certain kind of John Wagner story. It’s a sports story about eating contests that is contrived to make a pop culture reference that was about thirty years old when it came out. It’s the way in which Wagner thinks that the Pinball Wizard bit is so good that he comes back to it and hammers it in that pushes the Wagnerness of it all to another level.

-This is something that one can definitely say for Bad Mother — the references are contemporary. And while the humour may be obvious, it’s still funny: I loved “What you could do — and this might not suit everyone — is grow a nice clematis on him.” That’s such a perfect 2000 AD moment — what other comic would do that with the image of a bloody corpse crucified on a wall?

– Bad Manners, as our hosts say, is indeed great. One aspect of it that stands out is that it’s the most effective use yet of something that’s been introduced into Dredd in recent volumes, the occasional instance of Justice Department screwing up in a recognizable and realistic bureaucratic way. As when Dredd was sent to the wrong apartment a Case File or two back. This is very different from Dredd in the ‘80s golden age: whether or not it was presented as oppressive, the system was presented as *efficient* and essentially incapable of just making stupid mistakes. In this case, it’s not clear how Manners finds out about Boco’s call, but it’s obvious that he shouldn’t have, that someone somewhere was careless.

This might speak to the aging of the target audience. Children are obviously at the mercy of bureaucracies all the time, but they rarely have to deal with them directly themselves. Whereas one thing that every adult learns about is dealing with the consequences of some anonymous someone somewhere in some organization making a careless mistake that affects you — not maliciously, and not necessarily due to any special incompetence but just because, due to the complexity of modern life, there are a lot of little things that get done, over and over again, and sooner or later someone is going to $%^# up the details. Pretty much everyone has some horror story about thart, and I think it’s a peculiarly adult nightmare of what happens when the consequences of that are not hours on hold trying to get through to someone who can actually fix the problem, but, as here, murder.

Dredd’s mistake in the story is a bit different, though. It’s Dredd who, when they learn that there’s no trace of drugs in Boco’s system, dismisses it with “Too smart to use the stuff himself.” I.e., he’s fitting the facts into a preconceived narrative about what “creeps” are like. Which is something that Dredd does a lot in normal Dredd stories, come up with the (in other stories correct) narrative of what’s really going on. There’s something there about how Manners is able to operate because he’s exploiting the narrative of a conventional Dredd story. Which is not to say that this is not realistic and is how real police get away with brutality all the time — that too is sustained by narratives, as we all know.

– I didn’t dislike Helter Skelter as much as our hosts — it’s overtly a celebration of the comics of Ennis’s youth, but, you know, they deserve celebrating. It probably helps for me that Ennis’s 2000 AD is pretty much the same as my 2000 AD — he’s a little older than me, but that double-page spread is pretty much exactly all the classic characters from when I was young, and hits me in the nostalgia, whatever the quality of the art.

Which is to say, of course, that Ennis is very, very clear about why he likes Dredd, and it’s that he’s the ultimate protector of the in-group against the bad people who threaten the in-group, and everyone else should shut up and let the protector do what they have to do. “You’ll do as you are told.” I’ve commented before that I think that has to have something to do with Ennis being a Northern Irish Protestant. What’s striking to me is that this was still his worldview in 2002, four years after the Good Friday Agreement.

I’ve never been an enormous Ennis fan, although I’ll admit that when Troubled Souls came out, it was a big deal for me and my friends, because it was someone from Ireland being a success. (This can be summed up as the “Chief O’Brien effect.”) But working through his Dredd work in reading along with our hosts has convinced me to be much more critical of Ennis than I was, and much more sceptical of his hostility to analysis of his work, because of what really does seem to be an outlook on how life is that’s rooted in sectarianism and disbelieving of the possibility of compromise with the (always conveniently awful and irredeemable) other side. I’m not saying that Ennis is consciously aware of any of that, of course, but I don’t think there’s any way to pretend that, “So, how would this apply to Northern Ireland?” is not (a) a sensible question and (b) one that has an obvious answer.

Obviously, I’ve said a lot of that here before, but, as noted above, it’s the absence of any movement given how radically things had changed by 2002, and how hopeful things at least seemed, that’s so disturbing here.

– Which brings me to Gordon Rennie. I felt in the last volume that Gordon Rennie had a touch of Garth Ennis’s fanboy admiration for Dredd. There’s a little note here in Couch Potatoes that may (or may not) prove to be revealing, when Dredd responds to “the most dull-witted and easily susceptible of subjects,” with ”In other words, about two-thirds of the city’s population.”

This is a note that Wagner sometimes hits, and used to hit a lot early in Dredd, where Dredd and authoritarianism is, at least implicitly, a good thing, because ordinary people are childish and stupid. Dredd as the schoolteacher imposing discipline on a class of children. But I don’t know that Wagner often, if at all, has Dredd express such straightforward unironic contempt for ordinary people. This doesn’t feel like they’re children, it feels like they’re an “inferior” group.

It’s that the line is not played for laughs, I think — although to be fair to Rennie that may be a matter of Robinson’s art.

– I think our hosts might need to revisit some of the stories in the bad stretch a few Case Files ago. Because OK, Leaves of Grass is no prize. (One has a suspicion that Grant thought of the pun in the title, thought it was a lot funnier than it is, and then had no other ideas.) But the worst Dredd story ever? Worse than The Sugar Beat?

A few follow up comments:

2000AD’s store has Case Files 40’s release data as August, 2022, which I thiiiiiink means you’ll be able to do that as well without any interruptions to your schedule. Which, on the one hand is great, more Drokk, and you get to do Total War, which will be fun. On the other hand, it’s infuriating, because you are sooooo close to the Origins->Tour of Duty->Day of Chaos sequence. I would love for you to do a special closeout episode on just those works, since it’s both Wagner at his peak, and his swan song in terms of the strip. He’s still putting out one or two stories a year, and thank god for that, but that sequence really feels like a summation of his direct stewardship of Dredd. Plus, as Graeme mentioned it’s the line of demarcation between Current Dredd and where you are now, so it would be a great closeout to have Jeff end the podcast at essentially Contemporary Dredd.

Second, Voord, love the comments as always, but I have to disagree with your take on Ennis. While I completely agree on the impact the sectarian violence he grew up in had on him, I don’t at all agree with your Us vs the Other framework for his worldview. Not to derail Drokk into Ennis too much, since we’re done with him now, but the tension in his work has always been his deep love of the Touch Guy figure with his intellectual understanding of how toxic and horrifying that type of person can be. His go to story engine is an idealistic but slightly naive man being brought into the orbit of a wiser, cynical, willing to do what it takes mentor figure. The idealist will learn from and be tempred by their encounter with the older bastard, but always rejects the absolutism and nihilism espoused by the hard man which ends in a climactic confrontation where one or both of the two end up dying. If there is a survivor they reflect on either their exposure to the monstrous or are crushed by the realization of their own monstrousness. He does this in The Boys (Which has a boatload of other issues, oh god does it), it shows up constantly in his War Stories, both the actual series and his other war comics, his Unknown Soldier mini for Vertigo, it’s even Jesse and Cassidy in Preacher to an extent. In all cases, the break is some form of “Yes the world is amoral, and sometimes it requires terrible decisions be made, but you are still a monster and I will not become like you.” Which I think is the cornerstone of Ennis’ worldview, and the central fascination of his career. He’s obsessed with ethics in a world without order, and what it means to try to be a good person in that context, so his stories are always morality tales about people placed in extreme circumstances. Which is where his Tough Guy love ends up, I think. It’s not the will to power worship, it’s the ability to look at a situation where all the choices are bad and still make a choice that he finds inspiring. Essentially, he’s an existentialist.

It’s worth noting that the only times he makes the Hard Man characters his main characters are when he’s writing the Punisher or Nick Fury, and there the work is entirely about the fact that those are terrible, broken men who should not exist. In both cases they serve as vehicles for and embodiements of Ennis’ obsession with the horrors of the American war machinge and imperialism. As he’s said so many times before, he loves Dredd too much to attack him the way he does with Fury and the Punisher, so you get the unvarnished tough guy, shut up and obey me take you so rightly object to.

Surprised to find Helter Skelter is the basis for a 2000AD/Dredd board game released recently – https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/275034/judge-dredd-helter-skelter

It has Nikolai Dante as one of the other comic universes crashing into MC1, but the others line up with Ennis’ paen/elegy for his version (and really involvement with) the comic.