Previously on Drokk!: John Wagner has been joined by his long-term writing partner Alan Grant, as the world of Mega-City One comes ever more defined by the episode. We’ve survived the Cursed Earth, the Day The Law Died and even the Judge Child Quest. But can anyone survive… the Apocalypse War…?

0:00:00-0:01:37: We jump into the episode in a remarkably quick fashion, so eager are we to discuss Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 5, which covers material from 2000 AD Prog’s 208 through 270 — which is to say, far more than a year’s worth of material. Which makes it all the more surprising that the quality in this book is so high. A note on the podcast as a whole I’ll sneak in here: We’re so in our own heads that we never actually give the full names of the writers of the entire book; it’s John Wagner and Alan Grant, co-writing each episode. I mean, we’ve talked about them before in earlier episodes, so chances are everyone already knows, but yet.

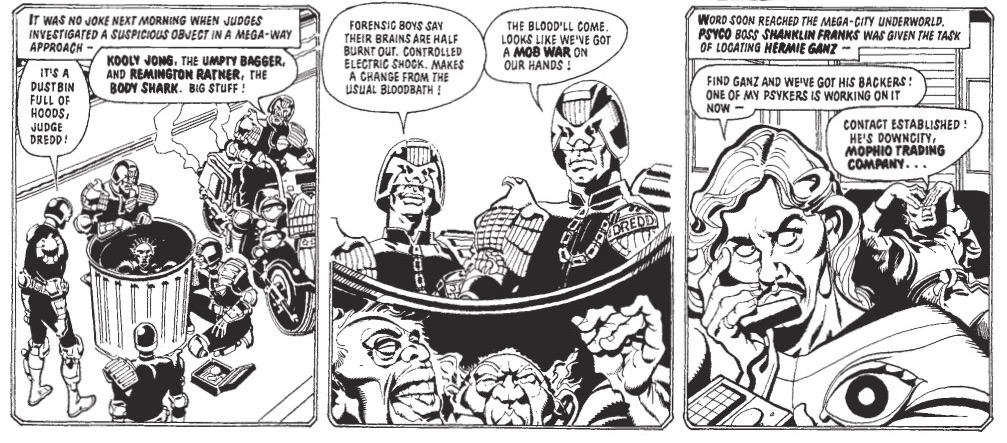

0:01:38-0:09:35: We just right into things by talking about how strong the book is as a whole, with almost no filler, and even the stories we think might be filler are particularly strong. The whole thing, I argue, reads like one larger narrative about the fragility of the block system (and, arguably, Mega-City One as a whole). We talk about that, as well as the dark humor especially present in this volume, and the ways in which Judge Dredd (the strip) uses continuity differently from other comics.

0:09:36-0:23:30: Is this volume so strong because Wagner and Grant have found the perfect balance between world building and storytelling? That’s something I suggest, while we also talk about the two writers — and, specifically, their work in this volume — as being an unrecognized inspiration for a lot of subsequent British writers. Also, is the work in this book a response to 2000 AD’s then-contemporary interest in the concept of “future war,” and how would “The Apocalypse War” storyline stand up against fellow 2000 AD icon Pat Mills’ Invasion strip?

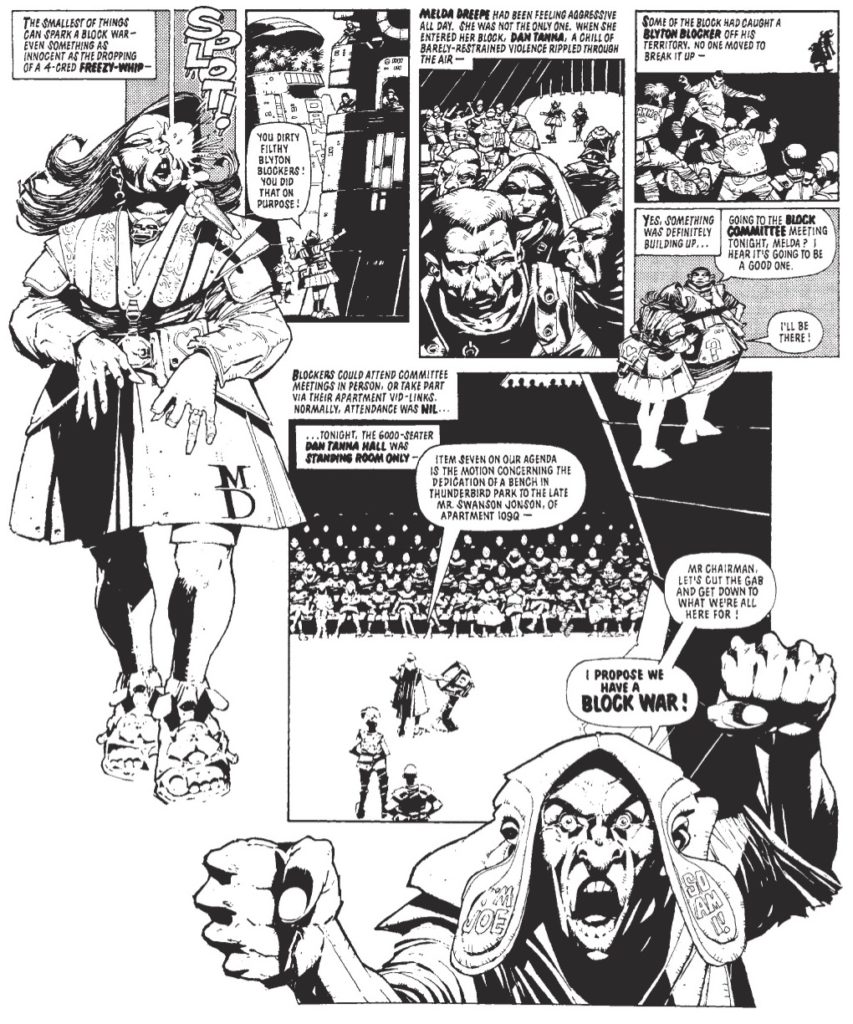

0:23:21-0:31:49: Intentionally or otherwise, Vol. 5 is very clearly a book of two halves, with the first half managing to create an atmosphere and understanding in the reader’s mind that supports the final “Block Mania” and “Apocalypse War” storylines. We discuss how organic this feels as a reader, while Jeff points out something that I’d missed: The first half of the book also contains a storyline which is, in many ways, the overarching structure of this volume in miniature.

0:31:50-0:39:10: We take a brief detour to talk about one of the so-called filler stories, which nonetheless proved to be surprisingly chilling to both Jeff and myself. Can a story about a man with a gun read “innocently” any more; when it first was published almost 40 years ago — and in the UK, where gun violence is far more rare — was it as removed from reality as the other, more outrageous, strips that surrounds it?

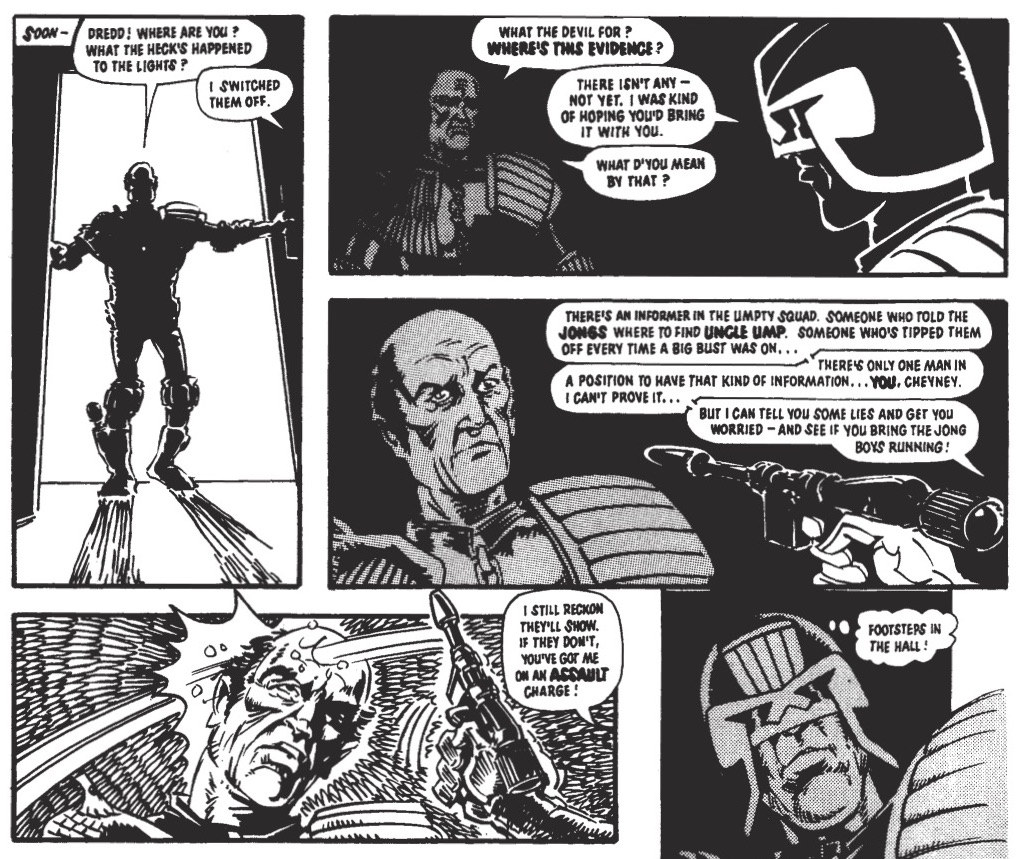

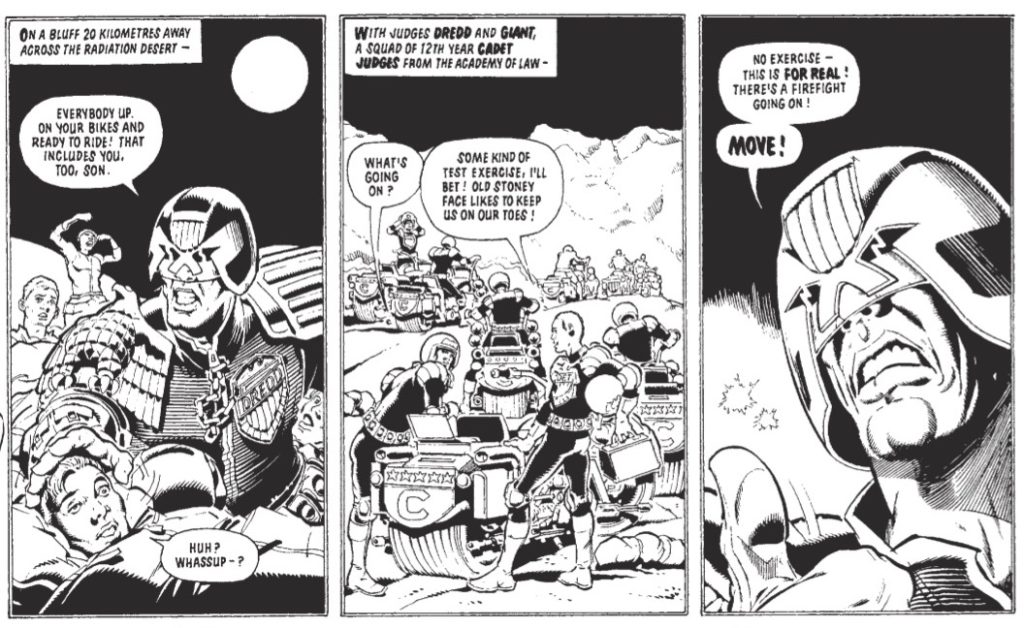

0:39:11-0:50:01: If the book is, as I argue, actually two books, then it’s impressive that the “lesser” of the two is still some of the best Dredd there is. Jeff and I talk about our love for “The Hotdog Run,” a three-parter that precedes “Block Mania” and “The Apocalypse War,” as well as touching on something that’s important and somewhat new about this volume’s strips: The suggestion that the Judges are, in fact, far more fallible than they’d previously been portrayed — something that is necessary for what’s to come.

0:50:02-0:58:05: Another detour of sorts, as the artists in the volume come up for discussion. We bid farewell to both Mike McMahon and Brian Bolland with this volume, both of whom go out on top — that McMahon art in particular is amazing — while Colin Wilson arrives with some art that suggests that Bolland’s influence will remain in this strip for quite some time. Even inside the mind of Ron Smith, who isn’t otherwise a particularly Bolland-esque artist, portrayals of Dredd aside.

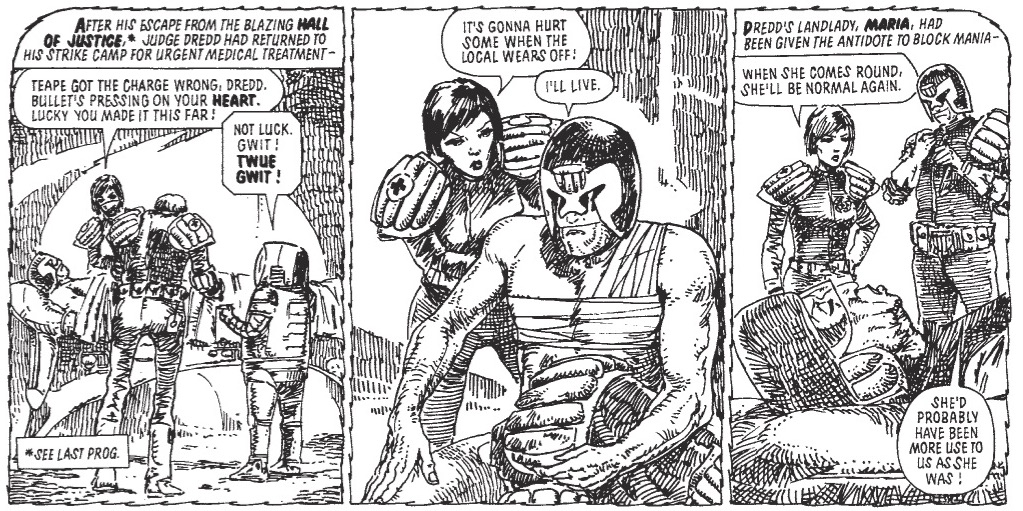

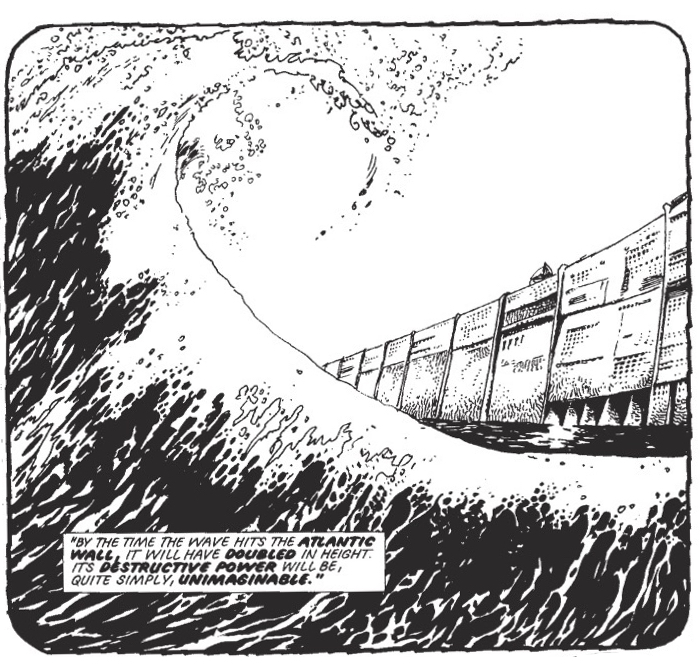

0:58:06-1:04:04: If Joe Dredd is the eponymous lead of the strip, Jeff argues that Mega-City One is the primary co-star, which is why what happens to the city in this volume is so impactful; Wagner and Grant essentially manage to convince readers that the big co-star is going to get killed.

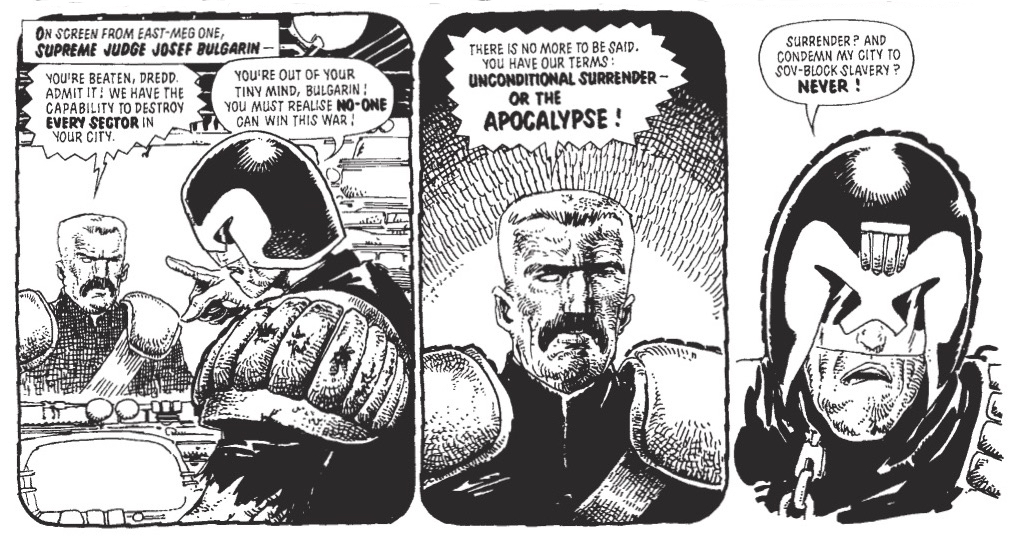

1:04:05-1:15:12: We finally arrive at the “Block Mania”/“Apocalypse War” cycle — which lasts 34 issues, all told, and is one massive story that pretends otherwise. There’s a quick plot synopsis, and then we’re into talking about how bold a piece of storytelling it is, and how it continually wrongfoots the reader in a genuinely impressive manner, continually outpacing expectations. As Jeff argues, it not only lives up to the hype that surrounds the storyline, it transcends it. (Bold, I know, but really; this is entirely earned praise.)

1:15:13-1:27:41: As bleak as it is — and “The Apocalypse War,” especially, is one of the most bleak storylines in all of Dredd, if taken literally — there’s something surprisingly entertaining and enjoyable about these two storylines. Is it simply that we’re ready for anything, even scenes of Walter the Wobot and racist stereotype housekeeper Maria, to break the existential horror of what is happening elsewhere? We also discuss the names of the various city blocks that show up in “Block Mania,” and what might be the most unlikely-to-be-picked-up-by-the-kid-demographic reference in Dredd yet.

1:27:42-1:34:33: Let’s take a moment to appreciate just how staggeringly good the art is throughout the 25-part “Apocalypse War,” with Carlos Ezquerra returning to the strip for the first time in five years to draw the entire thing. Jeff describes his take on Dredd and the world of the strip as “understated iconic,” and that feels entirely appropriate. There’s discussion of his style, of an amazing method of differentiating a flashback scene from the “present day,” and of the ways in which Ezquerra was like Jack Kirby.

1:34:34-1:49:28: This leads onto a conversation about Ezquerra’s past drawing war comics for the UK, which turns into a discussion about the influence of British war comics — which John Wagner had also worked on, of course — on this particular strip. I make the suggestion that, for the length of “The Apocalypse War,” the strip actually stops Judge Dredd as we know it, even as the storyline makes the most explicit argument for Dredd being a broken, damaged, dangerous man instead of a hero. Jeff runs with this, and points out the criticism of Dredd present in the story’s conclusion, which implicitly recasts the entire storyline as Dredd’s fault in an entirely new way.

1:49:29-1:59:02: Dredd is actually missing for significant chunks of “The Apocalypse War,” and we talk about the strip growing past him for this particular storyline. Also discussed: Carlos Ezquerra’s fine art inspiration for one particular panel, and the fact that I read this while watching HBO’s Chernobyl, which made for some strange parallels. (Something not mentioned in the podcast, but consider this an extra: I wondered how much influence the iconic British anti-nuclear war TV drama Threads had on “The Apocalypse War,” and the answer is none; it came out afterwards.)

1:59:03-2:03:42: As we start to wrap things up, Jeff answers the traditional question: Would this be a good place to start reading Dredd? Despite having compared “The Apocalypse War” to Watchmen, he argues against it, thinking that the book requires the build-up offered by earlier volumes; I also think it’s not the best idea, but mostly because “The Apocalypse War” would utterly skew new reader expectations of what Judge Dredd actually is, as a longform narrative and give false expectations of future volumes.

2:03:43-end: We finally head towards the exit sign by talking ever-so-briefly about the fact that this is actually the 400th episode of Wait, What?, as we close out of month of 10th anniversary programming. (Thank you, everyone, for listening, for however much of that decade you’ve been there for.) Then, as ever, we talk about our Instagram, Tumblr, Twitter and Patreon accounts, and Jeff sings us out. Happy Apocalypse, everyone…!

If you want the direct link, here it is: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp5.mp3

Thanks for another entertaining podcast.

I’m surprised that you put the blame for the apocalypse war so squarely on Dredd’s shoulders for not bringing back the judge child. How you forgotten that every single one of his predictions totally screwed over the recipient? Mega City One would have been fucked so much worse if they’d had that little bastard around. /Puts on “Dredd Was Right” t-shirt.

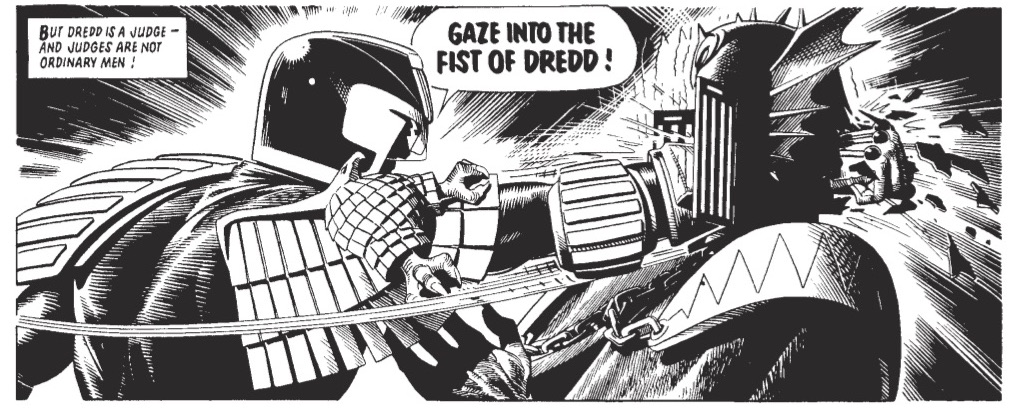

Overall I found Block Mania and The Apocalypse War engaging but was not very impressed by the rest of this volume. Some parts were complete trash, e.g. the “assassin” monsters from the cursed earth. I found the crime files kind of tedious, the way they took the name of an old crime and banged its square peg in the round hole of a future crime grated on me, e.g. numbers, white powder. And while the character moments for Dredd and Giant in The Hotdog Run were excellent, the overarching story had way too much of people doing stupid things for the plot to move. Now I’m not very fond of the Dark Judges in general, but everything is forgiven for the Fist of Dredd line, it’s that good. :)

Dredd in general: I realise “Future Shock” is a 2000AD thing, but it really bugs me when characters in story uses it for something relating their present.

Thank you for the podcast ! Apocalypse Wars was great indeed !

I just wanted to say it was a pleasure hearing Jeff talk about Gogol (a little correction though : in The Nose, Major Kovalev, the protagonist wakes up without his nose, and finally finds out the nose has been living its own life as a functionary). Everyone should read the Dead Souls (the short stories are amazing too). Contrary to what the name might suggest, this novel is not bleak at all and is actually extremely funny and absurd. It’s about a pretty bad con artist who tries to buy the property titles to dead serfs. That’s it for the book club !

Gogol is the best! But Wagner and Grant just seem to grab it as a random semi-famous Russian name: at least I don’t see any significance to the soldier having the name. On the other hand, one of Gogol’s most famous stories is “Diary of a Madman” (cf. “Diary of a Mad Citizen”), so somebody must have reading himself some Gogol c. 1981! Gogol’s satire, with towns filled with petty ridiculous self-serving idiots obsessed with status and the fear of the powerful, and useless bureaucracies out of control, doesn’t map exactly onto Dredd’s, but could well have been inspirational.

Thank you for the correction, Thibaut! As was pretty obvious, it’s been *wayyyy* too long since I’ve read Gogol (30 years, approximately)? I should give him a go again now that I’m old and beaten down…

Wagner and Grant will continue to scatter their Dredd (and Anderson, Strontium Dog and other) scripts with causal references to things they’ve been reading, especially the bizarre ravings of Lobsang Rampa. Spotting them is always a fun game to play!

My comments on Drokk! are getting ridiculously long, so I thought I might split them up. People, and especially our hosts, please let me know if I’m going on too much. I am aware that these comment threads are not my blog.

Our hosts picked out Diary of a Mad Citizen as distinctively something that was no longer science-fiction, but might have been at the time.

I think that might be idealizing the past. What’s striking about modern mass shootings is the frequency of occurrences, the role of social media, and an overlap with far-right political motivations that pushes it into the category of terrorism. (There’s also much more awareness of it as a problem with masculinity, but I think that’s more about our understanding of it than the phenomenon itself.)

But the possibility that men might just snap and use deadly weapons to take out their frustrations — that was something that people were well aware of in the ‘80s (and earlier, in particular in the ‘70s). The expression “going postal” dates from a few years after this. Kweeg is a typical 2000 AD absurdist exaggeration of something that had happened and was continuing to happen in real life.

But is it one of the more American stories in the volume? Possibly. See “going postal” — rampage killing is a disproportionately American phenomenon. It happens elsewhere, but it happens much more often in the US.

On the other hand, Hungerford happened in 1987, so the potential for this sort of thing was certainly out there in British culture. (British gun control was much less strict before Hungerford, incidentally.) And Diary of a Mad Citizen was published the year after John Thompson decided that the way to respond to being overcharged for drink in an unlicensed London bar was to come back and to burn the building down — killing 37 people.

I really enjoyed this volume, too and much more than I expected to. I didn’t like the Apocalypse War reading it week by week and never went back to it. This time I found it a dark chunk of fun. I don’t rate it as highly you guys, though, because it still says you could ‘win’ a nuclear war if you’re ruthless enough- even if it would be wrong. I don’t get the Sovs motivation for starting the war. There’s talk of slaves, but this is in a culture where people in the Mega cities don’t get to work because of automation. The Sovs don’t seem less technologically advanced. Why you’d take such an existential risk is under-explained. Finally, the notion that people from Russia would make US-ers more vulnerable by setting them at each others throats is absurd.

I know they’ve cropped up before in story before, but the Mega-Rackets really had me wondering how lawyers work in Mega-City One. Unless there are courts of some kind, do they just persuade the judge who has sentenced their client that they, the judge, has misunderstood The Law? So then the judge goes, ‘I see what you mean, good point.’

The artistic influence behind a lot of the book is Jean Giraud/ Moebius. Colin Wilson is liberally using the Jean Giraud style for non-Dredd figures and Ezquerra his love of Moebius throughout. The oddest influence artistically is Francis Bacon on Brian Bolland. It’s the image of Death on the page of that story, when he has his neck extended. I can’t quite source it, but it’s similar to an image from ‘Three Studies For Figures at the base of a Crucifixion’ Bolland later does a one page strip with his Mr Mamoulian character which are re-drawings of Bacon pictures.

One of the small delights of this volume was seeing Ron Smith draw Melda Dreepe so in his style and so immediately recognisable as the McMahon character.

Weirdly, I was going to praise TAW for one of things that you’re criticizing, and comment that it reflects its time in that it assumes that its young readers have a working understanding of Cold War logic and MAD.

Specifically, I think it takes for granted that you understand the logic according to which any imagined defence against nuclear war was – even though completely defensive in itself – viewed as highly dangerous. Because if either side believed that it could effectively defend against a nuclear strike, then its incentive to launch a nuclear war became overwhelming. This came up a lot in the arguments over SDI later in the decade. In this story that’s the Apocalypse War.

Similarly, when Dredd launches the TADs, he’s behaving completely logically according to the thinking of the time. Mutually Assured Destruction meant what it said. And the best way to convince the other side that you will destroy the world under all circumstances, no matter what, even if there is no point, is to genuinely and sincerely be the kind of person who would do that. This was standard in discussions of retaliation against a first strike, and there were military personnel on both sides who were ready to do essentially what Dredd does.

Insane? Certainly. But this was the world that we lived in.

This is a question about the awkward space between the world as it was when the comic was written and the world the comic has built. Maybe the game theory of M.A.D. would remain the same after you’ve has a nuclear war which has devastated most of the world, but it seems odd to me. Perhaps after your first nuclear exchange it just gets easier and the further degradation of your world and the resources necessary for life, a trifle. Bulgarin looks like he would have been alive during the previous nuclear war. I would have rated the story more highly with a more comprehensible motivation for him to hazard everything on a ‘calculated risk’.

That’s a good point. Intradiegetically, things shouldn’t work that way within Dredd’s world even if extradiegetically, it’s not that much of an exaggeration of actual 1982. I suppose it comes down to how much implausibility you’re prepared to forgive for the sake of contemporary relevance.

Obviously, if you actually are a Cold War-vintage capital-R Realist, then it doesn’t matter — these things are from that perspective inexorable products of the way states behave in certain situations. But since I’m not, and think that culture does matter…

The logic is quite simple and stems from real world. The shield is a winning advantage in a full scale war but only as long as you have it and the other guy doesn’t. So what happens when the shield isn’t quite perfect yet but the other guy knows you’ll be immune any day now? Either build a shield of his own or attack while he still has a chance. Ok, so now you know you have an enemy whose hand you just forced with your own development. At this point it makes perfect sense to shoot first and hope your imperfect shield can defend against whatever remains of the opponents capabilities.

In the comic the plan works perfectly. It almost came to point in the real world with men like Curtis LeMay at the helm who actively promoted a nuclear war as long as their side still had the decisive advantage.

In the comic universe one of the most important and understated points is that Judges are in power because they took over after democracy had failed and world ended in nuclear war (remember Booth in Cursed Earth?) with remaining population stacked inside monstrous cities, brutally repressed. The only reason Judges have to hold power, the guarantee of peace, is cast aside with no qualms in this one. It permanently changed the tone from “future cop tough on crime but fair to honest citizens” to “jackbooted fascist”.

I also find it funny that no one ever points out how Dredd tries to kill East Meg One twice. The first time he just doesn’t succeed so he has to try again. That’s half a billion dead he could have avoided: instead he tries incredibly hard to kill them again.

As Graeme and Jeff note, The Apocalypse War has a great, ever-building intensity that is so unusual: we’ve seen a million stories where the protagonists’ world is at risk of being annihilated by nuclear war; we’ve also seen a million “post-apocalypse” stories where the heroes’ world has already been annihilated before the story begins, but we rarely see the whole process–before, during, and after–which gives the Dredd strip a fierce depth.

I think, however, that Dredd’s actions are less capricious than our hosts suggest. Revenge is no doubt one of Dredd’s motives, and, yes, no doubt morally wrong, but understandable on an emotional level: Don’t you think many people, if given the opportunity to destroy the nation that had destroyed theirs with an unprovoked surprise nuclear attack, would eagerly press the button, ignoring any concerns of “proportionality”? I expect most would think it would be a crime not to. But more to the point, Dredd destroys the Sovs to save Mega-City One. He flips the switch so that the invading army will be demoralized, so the remnant of Mega-City One will be able to withstand the invaders, and ultimately be able to rebuild their society. Not only does Dredd say this himself (“We’re finished, but at least we’ve given the resistance a chance!” pt. 24, p.3), but his plan works: the remaining judges and militias rally against the East-Megs (pt. 23, p.3; pt. 24, p.1) “with renewed heart,” and at the end, are rebuilding their homes, rather than living under Sov slavery (Dredd “Condemn my city to Sov-Block slavery? Never!” pt. 5, p. 3 and the Chief Judge concurs). Jeff points out how the strip plays with familiar war-story tropes; Wagner and Grant give Dredd the usual war-story justifications. The difference is that they also show the horrible consequences of those acts. Of course Dredd is a radically ambiguous figure, but, to me, these stories feel more like a Greek tragedy, with no place for victory and no course of acceptable action available, not a critique of Dredd per se.

My own favorite story was “The Stookie Glanders,” which sent chills down my spine from the first panel. I guess I believe at some level that Wagner and Grant are correct: when humans find that tearing out the guts of benevolent, intelligent extraterrestrials is marketable, pretty quickly somebody will start designing the factory farms. To turn this horrible insight into a charming and funny two-parter–man! It floored me.

A favorite single moment in vol. 5 comes in “The Hot Dog Run Part 1,” in the two panels that end page five and begin page six. Ron Smith is the artist. The first panel seems to be a simple information shot of the Aquafarm the marauding mutants are after, with a kind of depth-of-field effect so we can see the plants close up and see what the characters are fighting over. But the fruit looks hella weird. Are those faces? What’s up with those creepy stems? After a momentary plunge into confusion, an explanation awaits on the following page: these are “munce plants, with their succulent head-shaped fruits.” The munce plant, references to which are scattered here and there throughout the volume, is a great tiny piece of world-building.

While I’m here, let me thank you guys for Drokk! I had never read Dredd before I heard you two singing its praises and I am loving it. And as always, your discussions are super-thoughtful. And congrats on #400!

It is interesting that you commented on Warren Ellis possibly being influenced by these stories. We know he was reading them, because in Prog 220 on a page entitled “1981 READERS PROFILES” we are told that “EARTHLET WARREN ELLIS has no difficulty obtaining 2000AD in his area, Benfleet, Essex, despite not having a regular order. Warren is thirteen years old and would like to buy model assembly kits of the 2000 AD heroes, as well as joining a Judge Dredd fan club. He also puts a Judge Dredd uniform at the top of his items for sale list, but rates the Tharg mask a lowly sixth place.” It was noted that “Each Earthlet Featured Here Wins £3”, which would have enabled the young Mr Ellis to get 20 Progs at the 15p cover price of the day. Equivalent to £57 today. Not bad!

This is absolutely delightful.

Reading in preparation for the next Drokk provides direct proof of Mr Ellis’ enjoyment of the apocalypse War. we now have direct proof that Warren Ellis was reading the apocalypse War. In the Nerve Centre page for Prog 282 we read:

“Dear Tharg, Thank you for the “Apocalypse War” epic. It was carved of the stuff of which legends are made. And now, as the people of Mega-City One look to the mammoth task of rebuilding, I wonder whether the ravaged Earth will finally know peace? Thank you for a classic. Earthlet Warren Ellis, Benfleet, Essex. £3 Winner.”

Tharg replied to say “The inhabitants of Mega-City One indeed have a massive reconstruction task ahead of them, as evidenced by the state of the city in Judge Dredd stories since “The Apocalypse War”. As to whether they are allowed to finish it in peace, only Script Robot Grover and the Mighty Tharg know.

The only bad news for Ellis is that given the price of a Prog is now 18p, his latest £3 will only get him 16 and 2/3 of them. But that would still be £47.50 today!

As usual, late to the game, so everything of import has been already covered by our hosts and the insightful commenters here. I first read Block Mania/Apocalypse War a few years ago as a way to dip my toe in the waters of Dredd. It was the first non-Batman crossover Dread I had ever read. While I enjoyed it then, I realized not having the context of Dredd and Mega-City 1 made some of the emotional beats fall flat (Giant and the Chief Judge’s deaths, and the appearance of Walter and Maria, for example). I was also incredulous at Dredd’s Reed Richards-like omniscience when he figures out relatively quickly that the Block Mania citizens have been infected by something. Re-reading it now, after 4.5 volumes of Dredd stories makes everything that much more understandable and enjoyable. This volume might of have portrayed the judges as always a few steps behind, but Dredd knows his citizens and his city pretty well, something I didn’t know coming into TAW suddenly like that. I would not recommend TAW on its own, but if someone just wanted to have a one-time spin with Dredd, I feel the entirety of Vol. 5 of the Case Files wouldn’t be a bad way to go.

One place where I had a different read from our hosts was when in part 2 of TAW, the Sov Judge Bulgarin says, “The people? What have they got to do with it?” which is mirrored on the next page with Dredd’s “The citizens? What makes you think they’d be interested?” If I recall, Jeff and Graeme viewed this as Bulgarin and Dredd being on two sides of the same coin, but I looked at this as more of a condemnation of the two political sides of communism (really totalitarianism) and democracy. In a the totalitarian communist state, the people don’t have any choice in the matter; in a democracy, people have choice but would rather ignore the situation or allow themselves to be distracted. Of course, it’s hard not to view Dredd as a fascist, but his statement doesn’t feel like something a fascist would say. The fact that there’s an image of people and their Block Mania battle behind Dredd, I think, supports this. You don’t even see the people in Bulgarin’s panel. Perhaps this is a consequence of trying to contrast Dredd with someone more fascist than he is.

Finally, thank you Graeme for explaining what those Restricted Case Files collections are! The description of them makes it sound like they just collect material too hardcore for the Case Files collections, which made me wonder if the Case Files collection were expurgated in some way. I’m not sure if citizens get a vote in Mega-City 1, but if you’re going to read outside the regular case files, I hope you include the Batman, Aliens, et al crossovers in there as well.

I think you have a point about the contrast between Bulgarin and Dredd’s “Citizens?” lines. They’re clearly in parallel, but that brings out the differences as much as the similarities.

There’s support for your argument later in the text. There’s a similar contrast between Dredd and Izaaks, who can’t kill Kazan, because he’s an “East-Meg Judge” and Kazan is his War Marschall. We know for a fact that Dredd, the ultimate Mega-City Judge *can* do that, because he already has in this very story — he killed Chief Judge Griffin.

I’ve floated here a suggestion that Dredd isn’t so much a fascist in the historical sense in these early stories (not consistently so, at any rate) — people (and “people” here includes Wagner and Grant themselves) say that because fascism and communism tend to exhaust our vocabulary for talking about these things. I think Dredd often reads more as an absurdist fantasy of liberal democracy minus liberalism and democracy: nothing but a desire for procedural regularity and order. One of the Enlightenment values that leaves Dredd with is the idea that no-one is above the law, and that’s what East-Meg One turns out to lack. Not so much democracy, but certain aspects of that type of political modernity minus democracy. Creating this very thin moral difference between Mega-City One and its enemy, and raising the question of whether that’s enough for us to side with Mega-City One.

Dredd as an absurdist fantasy of liberal democracy but stripped of all the signifiers of such is something I can see. That would put him in the exact same category as American police. You can see their antagonism toward democracy in just how they’ve but shutting down people’s right to assemble and protest in the U.S. since forever, all in the name of maintaining law and order. The judges never try to improve the citizens’ lives either; they only enact new laws to maintain their precious order.