We’re two issues into Dark Knight III: The Master Race by this point, and I’m even more at a loss about how I feel about the series. The second issue feels even less like a legitimate Dark Knight project than the first — and, at times, far more like a cover version; the interrogation scene on the second and third pages feels like someone processing a Miller influence than anything that Miller himself had any hand in, even the “consulting” credit he gives himself in interview — and, at times, far less like a Batman project, given the issue’s Atom subplot. And yet, I can’t quite shake the feeling that I’m appreciative of these shifts from expectation, and that I might even enjoy the strangeness that this series is more than I would a real third Miller Dark Knight.

I’m about to spoil the second issue for those who’re concerned about things, so look away now if you want to discover the twists for yourself.

The series, as is obvious from the end of the second issue, is about Bruce Wayne taking on an entire army of Supermen, thanks to the Evil Kandorians that Ray Palmer was duped into helping escape from the shrunken city. Yes, Bruce isn’t dead, despite the time spent in the second issue on an almost-touching story about his slow death, but that’s not a surprise; I doubt that anyone who read the first issue’s “Bruce Wayne… is dead” cliffhanger really believed it, so his silent return on the final page of the second issue feels overdue, if anything.

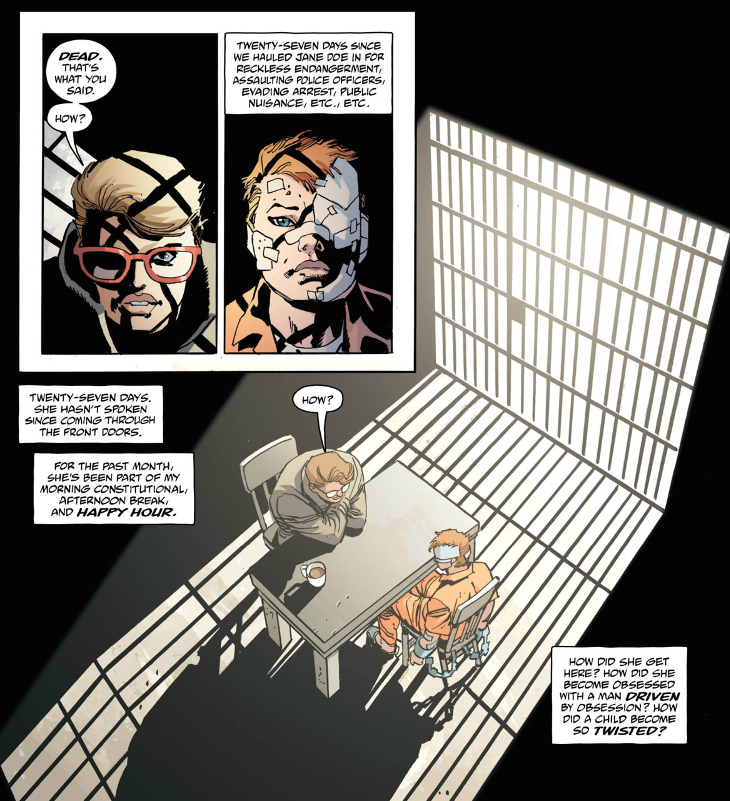

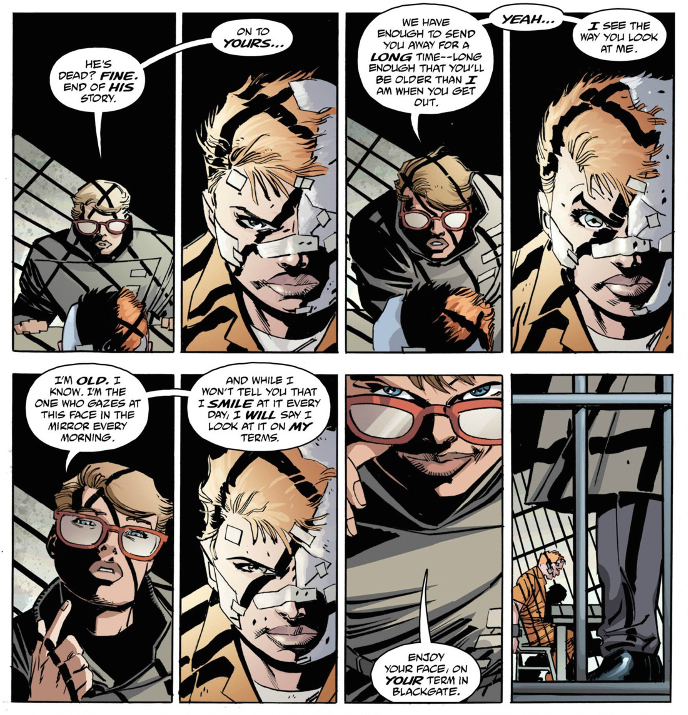

The entire “he’s dead/no he’s not” fake-out is disposed of so quickly that it leaves an impression of what’s the point?, to be honest; aside from providing a dramatic out for the first issue, I can’t see what it actually added to the story in any appreciable way. That’s actually my primary complaint about these first two issues: almost everything feels like prologue at best — the Ray Palmer scenes, the Wonder Woman scenes, the Batman vs. the cops moment from the first issue — and filler at worst (the majority of Carrie Kelley’s appearances in this second issue). The most interesting material of all has appeared in the mini-comic accompaniments to the main issue, which on the basis of the first two issues, act as prologues for developments in the last issue of the full-sized comic. As a creative choice, it’s both frustrating — why not fold this into the main book? — and oddly compelling.

Actually, frustrating and oddly compelling kind of sums up my feelings about the main book, too. This isn’t a great comic. It’s possibly not even a good comic — there’s certainly an argument to be made that it’s essentially a Geoff Johns comic that frowns more — but the old school DC fan in me gets caught up on the idea of the plot hinging on Ray Palmer de-shrinking Kandorians, or that we get to see a panel that explicitly references World’s Finest as a title. In the many, many ways in which the series feels like an exercise in nostalgia, it feels like a comic that’s almost explicitly anti-Millereseque. For all that Azzarello is consciously trying to evoke Miller, he’s surprisingly respectful towards things that Miller would’ve at least pretended to kick the shit out of, and the difference is striking.

Artwise, there’s no way around it; the highlights are likely to be the mini-comics each issue. Which isn’t to say that Andy Kubert and Klaus Janson are a bad team — Janson brings the best out of Kubert, for sure, and there are moments in the second issue where it works well (even if Brad Anderson’s colors can betray it at surprising intervals; the blood splatter background to the first page really should’ve been flat, instead of crudely rendered with highlights, for example) — but compared with Eduardo Risso in this second issue, it’s a poor second.

When we talked about the first issue in our roundtable last month, Jeff, Matt and I tried to put DKIII in a continuum with DC’s other high-profile longings for days of yore, Before Watchmen and Sandman: Overture. On the evidence of the first quarter of the series, it seems to fall firmly in the middle — not as morally objectionable as Before Watchmen, but also not as willing to go off on unexpected tangents as Overture. Whether a middling performance is what the audience of this book wants is unlikely, but who knows? Perhaps, despite evidence to the contrary so far, there’s something unexpected in the series’ future.