If I had to imagine the meeting where everyone discussed The Curse of the Crimson Corsair — which is technically the full title of Before Watchmen: Crimson Corsair, the prefix unused for reasons we’ll get to momentarily — then I’d imagine a conversation that went something like this:

“So, we’re doing all these Watchmen prequels, so let’s do a pirate comic.”

“You mean, like unseen issues of Tales of the Black Freighter, maybe the ones mentioned in that fake history of the comic?”

“Yeah, like that, but not actually Tales of the Black Freighter. Just a pirate comic.”

“Oh, okay. But it’ll serve the same purpose as Tales of the Black Freighter, right?”

“Yeah, sure. It’ll be a pirate comic.”

“So, it’ll be meta-textual commentary on what’s happening elsewhere in the prequels, then?”

“No. None of that. Why would anyone want to read that? It’s just a pirate comic.”

“But it’s a pirate comic as if it was created in the 1980s timeframe of Watchmen, or maybe some other point in comics history, surely.”

“No. That stuff’s dumb, that’s not why anyone liked that shit in the original Watchmen. It’s a pirate comic. That’s all it is. That’s all that people liked. Pirates. You’ve seen those Johnny Depp movies, right? There you go.”

“Can we have anything to make it relate to Tales of the Black Freighter, other than the fact that it’s a pirate comic? Seriously. Anything.”

“Fine. Whoever writes it can do it in that same purple prose. Happy now?”

It’s almost impressive just how much Crimson Corsair throws away, in terms of what made Tales of the Black Freighter work in Watchmen. It’s the worst of every world for everyone aside from those who really did just want to read a pirate comic, and even then, it turns out to be a shitty comic. That there’s literally no metatextual element to the entire project genuinely makes it seem as if everyone responsible — creators Len Wein and John Higgins, but also editors Wil Moss and Mark Chiarello — seemed to think that the selling point for the pirate sequences in Watchmen was only the genre, and nothing else. Worse yet, that there’s literally no narrative connection made between what the audience knew of Tales of the Black Freighter and Crimson Corsair underscores that impression; why not even try and connect this project to the characters of the original, even if you’re not trying to address any of the more highbrow (and more important!) ambitions of the sequences?

It strikes me, mid-rant, that Crimson Corsair isn’t alone in this; the 2009 Watchmen movie stripped out all Black Freighter material, choosing instead to issue it as a standalone direct-to-DVD animated feature, as if Tales of the Black Freighter has particular value outside of as a meta commentary on what’s happening elsewhere in the story. Maybe it’s me; maybe I’ve misunderstood the entire point of Tales of the Black Freighter all these years. Perhaps it really is just that people really like pirates.

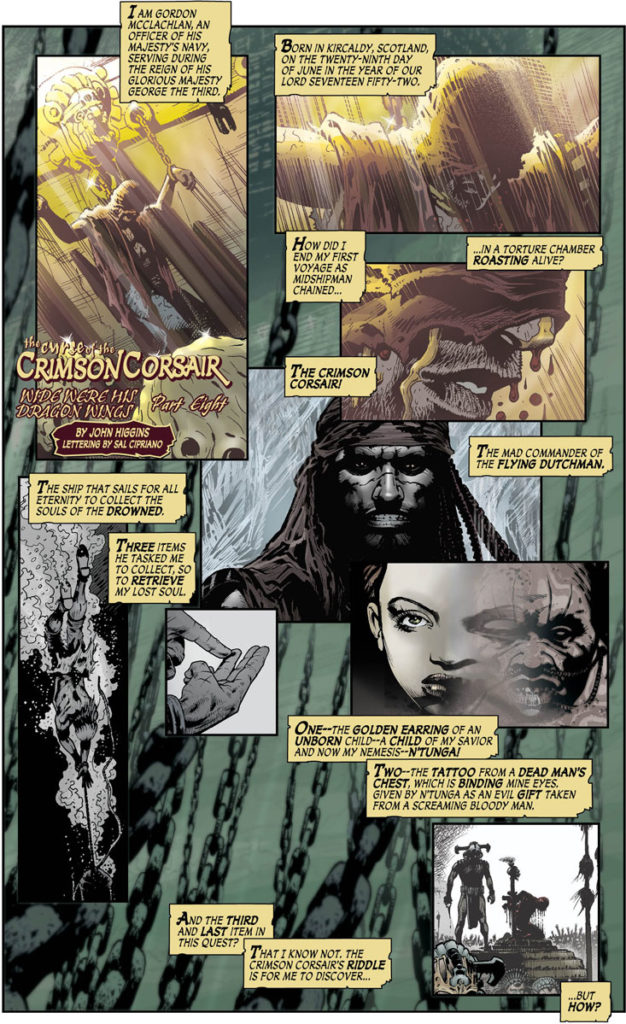

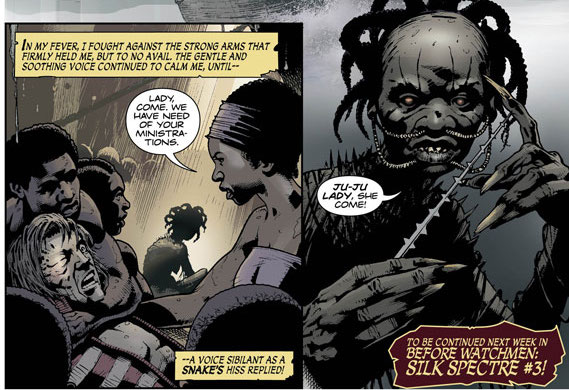

If that’s the case, though, Crimson Corsair would still disappoint. It isn’t just that the conceit behind the story is older than a shanty sung by a drunk old sea dog — short version: a sailor tries to do the right thing, is thrown off the ship he’s serving on, rescued by g-g-ghost pirates and then has to go on a quest to save his soul — but that everything about the writing, from the horribly overwritten narration to the choices made concerning character and circumstance, feels cliched and, often, offensive. (The introduction of a voodoo priestess with the dialogue, “Ju-Ju Lady, she come!” being a particular lowlight. Later, said voodoo priestess steals a baby, saying, “Ki ka, ki ki kia, I take baby. You not want baby.” This is something that was actually published in 2012, staggeringly.)

Despite all of this, there’s a sense that a different artist could have staged this in such a way as to make it feel like the EC-era comic the writing appears to want it to be; John Higgins doesn’t offer anything of the sort, however; the layouts are constantly overlapping with no seeming rhyme, reason or page design; the staging is consistently mundane, and the colors monochromatically muddy and indistinct. It’s not just a figuratively ugly comic, it’s a literally ugly one, as well.

Crimson Corsair clearly had some issues in its creation — Len Wein disappears as writer midway through the run, with Higgins replacing him (the shift is, at least, fairly smooth), and the story appears to end abruptly, perhaps suggesting that rumors of a cancelled one-shot that would’ve tied everything up have some truth to them — but there is nothing in evidence at any point of reading to suggest that this is a project that could’ve been great, but went off the rails at some point. It’s a Before Watchmen project that literally has zero to do with Watchmen in any respect other than it being a comic book like Watchmen is, and featuring a pirate, like Watchmen did. It is, in every single respect, a disaster.

Maybe that’s the point? Commentary on superhero readers’ completism?

It’s like 4’33” — the point is that you sit there being intensely aware of yourself as you read it. You become alive to the fact that you are reading an utterlessly pointless tie-in comic solely because it is part of the Before Watchmen series, even though it does not actually form part of it in any real way. And in turn, Before Watchmen exists as a whole solely to tie into a single solitary work to which it adds nothing of significance.

None of this is imaginable in another genre than superheroes even though Crimson Corsair is not a superhero comic but a comic in the genre that within Watchmen replaces superheroes. “Look,” it says, “I have turned you into the same sort of reader of pirate comics that you are of superhero comics, just as readers would be within Watchmen. I have done more than all the other comics in this series, in which people who are not Moore and Gibbons try to inhabit Moore and Gibbons’ world. I have made you – you! – inhabit that world. I have made you a character in Watchmen..”

And in this way, Crimson Corsair ruthlessly exposes the bleeding wound at the heart of Watchmen, that it is the superhero comic that Moore thought and thinks would and should forever destroy the reading of superhero comics by adults but which in fact serves and has served as a primer in how to read superhero comics for endless adults unfamiliar with the genre since its first appearance. In so doing, Crimson Corsair redeems the whole Before Watchmen project, finally giving it the purpose it up to this point has fundamentally lacked. It’s brilliant.

I’m still never going to read it, though.

Voord, by your own analysis, Crimson Corsair would serve at least one of the same functions as the original Tales from the Black Frieghter – as a harbinger of upcoming apocalypse. Of course, we’ll never know because like you I will never ever read it :)