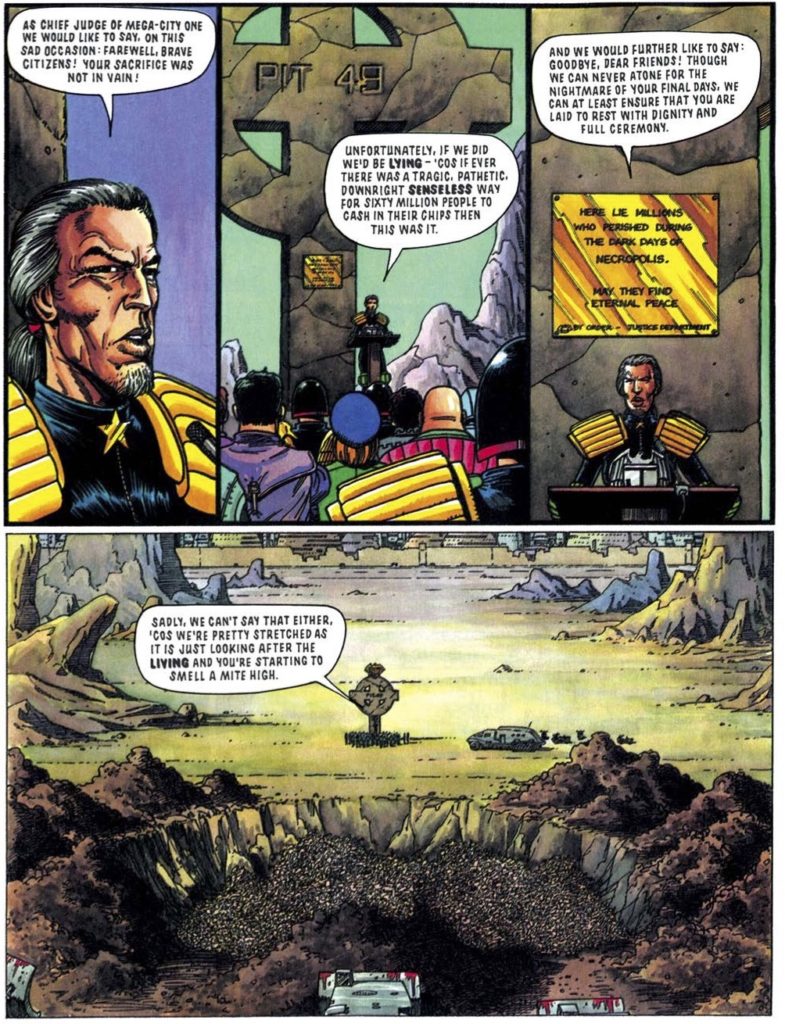

Previously on Drokk!: Disillusioned in the system, Dredd took the Long Walk and retired from being the law — only for Mega-City One to fall to the Dark Judges in his absence. Post-“Necropolis,” he’s back and nothing will be the same again, especially when it comes to Judge Dredd the comic strip.

0:00:00-0:01:44: Welcome back, dear Whatnauts, to the 22nd century that feels a little bit less removed from the current day with every single episode. As we quickly introduce things this time around, we’re covering two books: Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 15 and Judge Dredd: America — although, for those following along in collected editions, we’re only covering the first “America” story, and ignoring the two sequels for now.

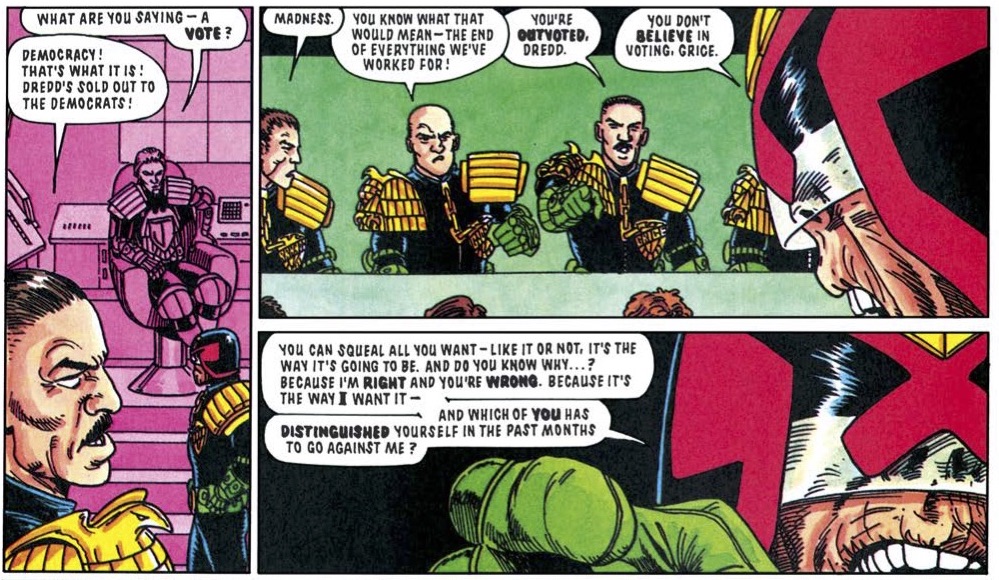

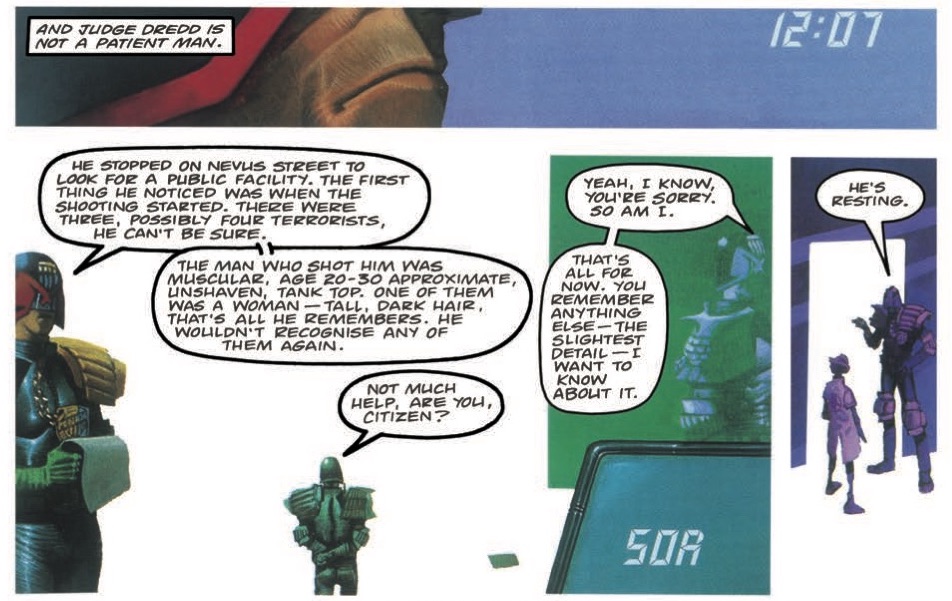

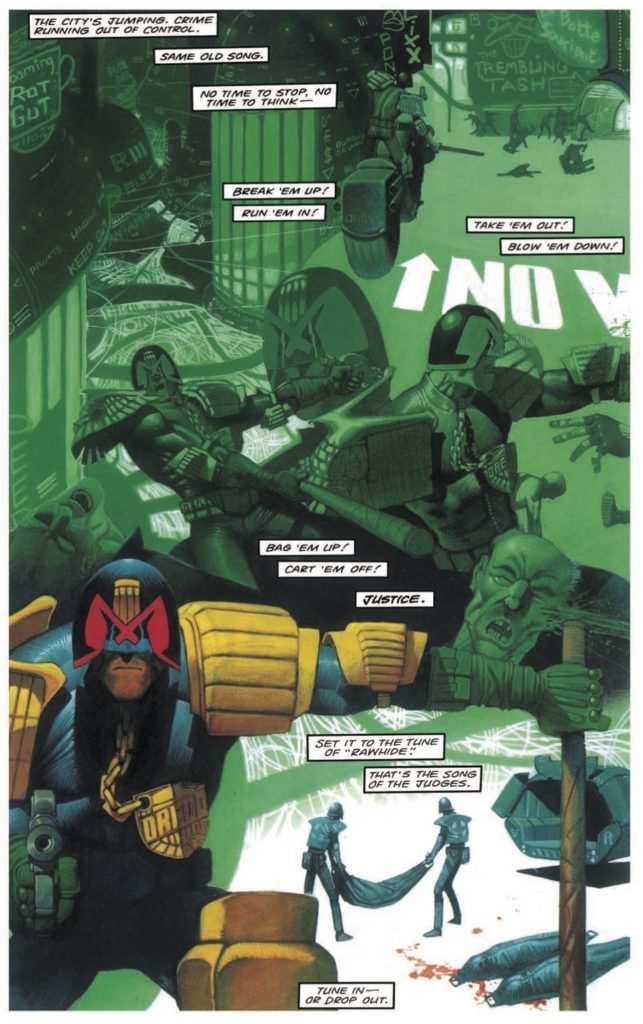

0:01:45-0:21:19: Taking the two books separately, we talk about Case Files 15 being a difficult book to read right now — both for the parallels with events in the real world, as everyone deals with police brutality and the ACAB reality, and also because it’s… not an especially good book…? That said, there’s a lot to enjoy here, and we dig into some of the good stuff, especially the way in which John Wagner struggles to deal with some tricky subjects, including the idea of Dredd as pro-democracy reformer. Also discussed: What role Judge Anderson could play in the future of Mega-City One, just how strong Wagner’s immediate post-“Necropolis” stories are, and Jeff and I disagreeing over Ron Smith’s artwork that opens the collection.

0:21:20-0:44:31: Of course, for some people, the appeal of Case Files 15 may be the arrival of Garth Ennis as writer, so we talk about that. Spoilers: His first stories aren’t very good, which means we’re discussing their sloppiness, Ennis’s apparent need to work as a John Wagner cover band, how his stories do and don’t follow Wagner — clue: it depends on what you mean by “follow” — and, generally, how they fall into the larger Garth Ennis pantheon, and what impact “The Apocalypse War” had on Ennis as a whole. Ennis isn’t the only writer letting the side down here, and we also talk about the disappointments offered up by Alan Grant and John Wagner in this volume, and everyone can enjoy Jeff’s literary detective work to identify the author of one particular story. (I just looked up Wikipedia to confirm, as it happened.)

0:44:32-0:53:16: Overall, is Case Files 15 Drokk or Dross? The answer probably won’t surprise you, but we pick out our favorite stories in the volume anyway, and also talk about the different artists on show here and what they fail to bring when necessary.

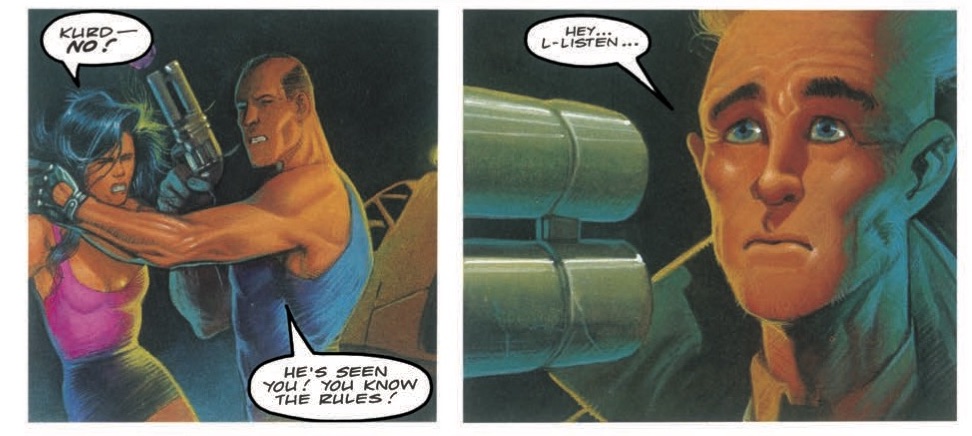

0:53:17-1:18:02: If I could point to the biggest surprise for me while recording Drokk! to date, it’s that “America” left Jeff as cold as it does, especially given that some of his reasons for feeling that way are things that, to be honest, I would have assumed would have been something that appealed to him. Is it that his expectations were too high, the current reality in which he’s reading, or Wagner’s pivot from broad condemnation to specific pulp story? We talk about all of this, while I reveal for just the latest time that I am willing to put up with all kinds of flawed work if I have warm feelings about it. (Really, I should be ashamed; really, I kind of am.) Am I riddled with nostalgia? Also: Where are the metaphors of “America”? And does the end still feel somewhat out of nowhere to everyone else? Commenters, I’m really looking forward to you weighing in here.

1:18:03-1:36:06: We continue talking about “America,” and weave slightly into whether or not this story is particularly timely right now, given everything that’s happening, and discuss whether or not it’s a story about the Judges or not. (Jeff isn’t convinced.) We also very briefly touch on whether or not Judge Dredd as a strip’s failure to talk about race is perhaps its biggest failure, in a way that only two white middle aged men can do.

1:36:07-1:39:07: Drokk? Dross? Thankfully, it turns out that not every book we’re talking about this week lets us down.

1:39-08-end: We wrap things up with me feeling nervous about the future episodes of Drokk! and what we have to look forward to, and the usual mentions of Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and Patreon. As always, thank you for listening and reading along.

Scattered initial thoughts:-

– I’m glad our hosts reminded us about how good the opening stories are in Volume 15, because honestly, so much of the rest of it was such a slog to get through that it was easy to forget that it opened with great, great stuff. But are those stories *really* in Volume 15? Obviously, they are in a literal boring sense, but they’re so closely tied to the previous volume, and not really what Volume 15 is about.

-What Volume 15 is about, for me, is losing me as a reader. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realize that I was buying and reading 2000 AD out of inertia, so I know that read into the stories covered in Volume 16. But eventually it did dawn on me that I didn’t actually think this was worth reading any more.

-And, yes, I’m afraid that a lot of that is that Garth Ennis basically didn’t hold my attention. Graeme McMillan nailed it: Ennis is writing Judge Dredd fanfic. Our hosts are 100% right that the longer Ennis stories drag, and being *slow* is the worst crime that Ennis could have committed against the 2000 AD that he read and loved when growing. But leaving the pacing issues aside, a lot of this is conceptually about revisiting Wagner & Grant ideas.

Some of those ideas are pretty good as fanfic goes: Death Aid is not the least amusing idea ever to appear in the comic. But Ennis has a fanfic-y tendency to miss the point in his love of the material that he’s emulating. About the only really interesting thing about the original Hunter’s Club story was that Dredd lost and the evil bastards got away with it. Because that’s what rich people do. This story seems to have been written out of a desire to undo that defeat, out of a sense (see esp. the final panel) that Dredd just can’t be allowed to lose.

– Which is the big problem: Ennis *worships* Judge Dredd as a character. Its more than just that he likes Dredd to be a bastard. Again and again in these stories we see Ennis allowing his inner 13-year old fan to shout at us that Dredd is tough and hard and intimidating and violent and cool and the bestest character ever.

-One place where I think this really manifests in in Ennis’s remarkably insensitive handling of Silver. There was no reason to revisit Silver’s fate, given that Wagner had more than adequately addressed it. I don’t think this is editorial fiat for that reason – editorial had already gotten this story, if they wanted it.

And when Ennis does it, his Silver bears no resemblance to the character that Wagner had been created. In fact, this is a hatchet job. It is hard to believe that this is not designed to insulate Dredd from Silver’s bad decisions that led up to Necropolis – decisions that Wagner had presented as the consequences of the *system*, and so not implicating Dredd as an individual, but definitely implicating Dredd as a *judge*.

Ennis wants to exorcise all that by contriving a moment in which Dredd declares Silver to be clearly guilty and derelict in duty — someone who should never have been a judge in the first place. (The presence of Hershey as a point of contrast is significant.) By implication, the system, and with it Dredd, is not to be viewed as the problem in any way. Just the particular individual who happened to be in power.

-That’s where I get a little uncomfortable. Ennis notoriously tends to retreat into anti-intellectualism and mockery of pretension when subjected to any sort of critique of his love of brutal violence. But the man is a Northern Irish Protestant.* There are a lot of complexities there [insert standard discussion about IRA terrorism, the South’s erasure from collective memory of atrocities committed against Protestants in the ‘20s, historic nationalist exclusion of Unionism and Protestantism from essentializing visions of a Catholic Ireland defined by opposition to Britishness, etc. etc.]. Loads of blame to go around on all sides.

But at the end of the day, writing a story to deny any guilt in the system so that you can unequivocally celebrate your brutal hard man police hero cracking down on people — maybe not the best look, in hindsight?

*Full disclosure: I’m the child of a mixed marriage, and one of my parents is a Protestant from the North. Not sure exactly how that affects my reaction to Ennis here, but I’m sure it’s playing into it in some way.

More scattered thoughts:-

-On Emerald Isle, I’d be grateful if David Morris could give me the benefit of his local insight on a particular point. Is there some Northern Irish fetishization of St. Stephen’s Green that I don’t know about? Do children from Belfast go on school trips to Dublin and have their teachers lecture at them about its tremendous importance?

I mean, St. Stephen’s Green is nice. Counts as a local landmark, definitely. Good place to see seagulls murder ducklings. But it’s not *special* in the way that Garth Ennis seems convinced that it is.

(Also, why *does* Ennis find the name “Kevin” inherently funny? )

-Beyond that, I have a feeling that the origin of Emerald Isle goes like this:

”So, Garth, since you’ll be taking over from John, what are your plans for Judge Dredd?”

“Well, I want to start by bringing back the Hunter’s Club! And I’ll have Hershey in my stories. And Dekker! Remember Dekker?”

“Well, yes, Garth, but we were wondering, ah, how can I put this, do you have anything of your own that you can bring to this? We’re hiring you because of Troubled Souls, you know.”

[Pause.]

“Umm…Dredd goes to Ireland?”

-The basic problem with Emerald Isle has been noted by Michael Carrol. On the one hand, it wants to attack patronizing Irish stereotypes (fair enough), and on the other, it’s got terrible bits of Oirish dialogue in it like “That Dredd’s a quare fella.” Also, guns that shoot potatoes. Ennis trades in what he’s allegedly attacking.

There’s a related point that American commentators on the story seem to miss. I encounter an American assumption that the markers of Irishness in this story are clearly in-group markers for Ennis’s own group. I think it’s more complicated than that, because (you guessed it) he’s a Protestant from the North.

Emerald Isle is about Ireland, but it’s more about the South than the North. Murphyville is a conurbation extending from Dublin to Cork on the map – it could go further up the coast to Belfast, but it stays confined within the Republic.

(There’s an inevitable incoherence here. Because it’s a mini-Mega-City, Murphyville has to be urban. At the same time, those patronizing Irish stereotypes are of an essentially rural Ireland, so the two have to sort of co-exist in the same place in some unclear way.)

Not all the markers of Irishness within the story exclude Northern Irish Protestants per se, but some of them do. The Irish tricolor is everywhere in this story. Green is all over the place as the official colour of the government and public services.

(The significance of green as a color would be more evident when this story appeared. At the time, the Republic basically looked like an alternate version of the UK in which anything that was painted red in the UK – postboxes, buses – looked exactly the same but was painted green. I can still remember it jarring me when the buses stopped being green.)

That’s the thing – this is about ideas of Irish nationality that are coded as nationalist, written by someone from the Unionist community. It’s as much playing the John Wagner game of stereotyping from the outside as it is operating from the inside, because Ennis is in a position where he can do both simultaneously, be Irish and not, or at any rate not these Irish, at the same time.

But the fact that the story is about Irish nationalism brings us to the fact that it’s about terrorism, which is not, given the context of the time in which it was written, all that surprising. Terrible, incompetent comedy terrorists, admittedly. But terrorists (who call themselves the “Sons of Erin” – the nationalist coding is not subtle).

There’s a good cynical 2000 AD point in here, I think, and it’s a shame that it got mixed up in the less good aspects of the story. The IRA committed horrific crimes in the name of Irishness, and meanwhile the South was busy commodifying Irishness to make money off tourists – which, from a certain perspective, is exactly the right kind of dark comedy gold for 2000 AD.

-This is very much a product of its time in another respect. Note that it is Brit-Cit corporations that are responsible for all this, and the logical future for Ireland is to be nothing but the tourist industry. This is written from a point of view that cannot imagine that there would be a time when Ireland would be, per capita, much wealthier than Britain, and the Taoiseach would serve for the readership of the Guardian as the designated “If only our Prime Minister were like that” figure.

-I did appreciate that Steve Dillon drew on the Four Courts for the Irish judge HQ. Generally, the Irish judges are also a very solid design, with nice little touches like Joyce’s tricolor sergeant’s stripes. In fact, the stylized harp badges are maybe a little *too* good – they look a little too sensible and plausible for Dredd’s world.

Okay, before I move on, I’ll have a go at answering a question about America: ‘Mr Jeff, Mr Jeff, please, please, is it ‘The Crying Game’ by Neil Jordan?’ Is this an example of that old 2000Ad standby, I just saw a thing I could use? If I’m right, it’s an odd coincidence, considering what I’m going to be writing now.

So, following Voord, I’m a Northern Irish Protestant, Presbyterian upbringing, for those of you alive to the distinction between the Established Church and the Dissenting tradition. Which is a bit of an issue. People outside of Northern Ireland want to know what you are to put what you say in context, but that context is every bit as important to the conversation. It’s a question that is only asked in Northern Ireland when the conversation has gone wrong. It’s a threat. We gently establish who we’re talking to by way of names, or names of schools, etc.

My school did take us on a school trip to Dublin at the end of the first year of our secondary education, 12 and 13 year olds. I don’t remember being lectured about the importance of St Stephens Green, but rather doubt it. Young protestant children are not (or certainly were not ) taught Irish history. Presumably because of the notorious unreliability of the young in ethical matters. I remember three things about the trip, shaking the mummified hand of a crusader in the crypt of a church, a modern bank, which was suspended and our train went over a bomb on the way there. Spoilers, it did not explode. Our train wasn’t the first to go over it. I don’t remember who planted it. It was in the paper by the time we were going home. We made jokes.

So, Emerald Isle is full of a fine Northern Irish Protestant contempt for Catholic Ireland. Voord says it doesn’t exclude Protestants per se, but it’s pretty pointed. It’s deplorable and the set up makes little sense. Admittedly, that points to ill considered matters in the Dreddoverse, all the places that would be most nuked remain the centers of power.

I read Troubled Souls when it came out, but at this distance remember little apart from an earnestness Ennis subsequently decided his writing could do without. Apart from that, I think his writing about Ireland displays a false equivalency, that both sides are violent, ignorant headbangers. There are very terrible people on both sides, as it were. Not much acknowledgement of systemic oppression.

You’re not the only one who wondered about a potential influence of The Crying Game on America — but The Crying Game came out in 1992, and America was published 1990-1991, so I guess that’s out the window.

(Well, since we’re going *that* full disclosure… The Northern Protestant side of the family is Church of Ireland.) The bit about St. Stephen’s Green was a joke, and apologies for not being OTT enough to communicate that. I don’t think that Ennis had ever spent much time in Dublin.

(In “You picked that name at random off a map, didn’t you?” we have Raheny making an appearance.)

As for Troubled Souls, it might *seem* earnest, but it’s possibly the single most cynical thing that Ennis has ever written. He’s been completely open that he was deliberately trading on the fact that he was from Northern Ireland to break into comics — I think we can all agree that Pat Mills was probably a pretty easy mark for that particular con.

The critical, fatal flaw of Garth Ennis’ Judge Dredd is that deep down, Ennis doens’t think Dredd’s a villain. You’ll understand that when you get to “Democracy now!” Garth is really an ‘ole fascist at heart, no matte how much whining he does about Corporations.

Of course, it could be argued that while John Wagner doesn’t consider Judge Dredd the hero, the citizenry of Mega City One are portrayed as so hopelessly stupid, violent, and unworthy that, in the end… he might as well be the hero.

Ennis’ end to the election storyline is… troubling, shall we say. I’m sure I’m going to go into a lot more depth next Drokk, but you’re right; he certainly seems to think that Dredd is the hero.

By the way, I know you guys let Garth off the hook with the Boys, but after reading Dear Becky, I suspect you’ll want to take said hook and ram it right into his chin.

…This almost makes me want to check that out.

Reading “America” was a straight-up gut punch, and it’s been a long time since something I read left me feeling so unsettled, agitated. I have to give it to both sides of the argument in this one: I get where Graeme is coming from, because Benny is the very definition of an unreliable narrator, whether because of his blind love, his rose-colored glasses for the past, or his abject fear of the judges. But, to Jeff’s point, making Benny the POV character, our only entryway into the story aside from our accrued familiarity with Dredd, robs the story of the power it could have had by either being told through America’s eyes or through a dispassionate third-person narrator, as most Dredd stories are told. We’ve seen enough cits like Benny populating Mega-City One, we don’t need another simp tour guide. I think Wagner could have still shown his white, liberal handwringingness in Benny while telling the story through America’s POV. In fact, given the current state of affairs (“Yes, racism and police brutality are bad, but we shouldn’t loot and riot.”), I think it would have been more beneficial for Wagner not to put up a mirror, but to show how Benny’s tepid liberalism is seen by those actively fighting for justice, i.e., America and, potentially, the other democrats. Unfortunately, we’re left with sad sack Benny, who followed the rules and got rich off them, but he forgot what happens to those who don’t follow the rules, and he gets America killed. Then, the ultimate affront to America’s beliefs–he takes over her body, subordinating it to his will in the way the cits are subordinated to the will of the judges. I will say it was a nice touch that he doesn’t have complete control of her body, much in the way the judges don’t have complete control of the will of the cits.

There is an important angle to what Wagner is doing in America that I think has been missed so far, which is the extent to which Benny is the viewpoint character of the story because he’s a stand in for the 2000AD audience. Wagner is writing America at the point where he knows that Dredd is going to continue beyond him because there is a hunger for more Dredd stories that will never be sated. I cannot believe he wouldn’t fold that awareness into the story that he admits was his attempt to sum up his thoughts and feelings about Dredd and his world. So America can’t be the main character, because making her the main character that we identify with lets the us off the hook when Dredd kills her. We know that America is right, and it is tragic that Dredd kills her, but we the reader still get the catharsis of identifying with her while she marches up the stairs carrying the flag to her death. Further, it would just be repeating the ending of Letter from a Democrat. By making Benny the main character, the audience becomes complicit in betraying America to the Judges. Benny’s about the age of the average 2000AD reader, or slightly older. He’s grown up and experienced most of the major Dredd events (even if he missed the Apocalypse War by being out of town, he would have been in high school through the Cursed Earth and Judge Child stories) that the readers have read for the last decade and change, and the fact that he’s a Nice Guy with possessive obsession for America probably hits closer to home with a section of the readership than they would like to admit, and is sadly still relevant in comics as we’ve just seen just this week.

(If this was two months ago, I’d have talked about the audience wanting to believe they would be America in a police state, but actually more likely to be Benny, just trying to stay out of trouble in a system they know is fucked. That was before two weeks up uninterrupted protests, which is both heartening to see and a fucked up reaction to them.)

Benny’s inability to commit to America and her fight, even when he knows she’s right that the Judges are horrible, is the same moral problem that faces every reader of Dredd. Yes, the audience knows Dredd is the villian. Yes, we know the system he represents is horrible and destroys everyone inside it. And we love the strip anyway, and show up every week for more, guaranteeing that Dredd will keep beating protesters and Mega City One will go through a mass casualty event every five years, because the audience demands it(!). I cannot see Wagner, aware of that dynamic, writing a straight forward tragedy that doesn’t turn the finger back on the audience. So Benny is the character we the audience are forced to, if not empathize, then at lease identify with, and in so doing we become just as responsible for killing America as Dredd is. Because we as readers don’t want America to succeed in toppling the Justice Department.

In story, America can’t win because the Benny’s of the world will always betray her, and outside the story America can’t win because the audience won’t let her destroy their ability to read more Dredd.

This is a great piece of analysis. Nothing to add – I just wanted to say that reading Beeny as a stand-in for the longtime 2000 AD reader really crystallizes a bunch of things about this story for me.

In particular, I didn’t like America all that much when it came out. I can’t remember entirely why that was — I have a vague sense that I might have felt that it was shouting at me how profound it was when I couldn’t see what it was saying that deserved its self-importance. But I liked the story more this time around, and I think Jared has pointed out to me, at least, what it was that was interesting there.

A couple of other scattered thoughts;-

-Our hosts felt that Wagner’s Dredd in America was not the same as Wagner’s Dredd in the contemporary 2000 AD stories. I’m not so sure. Is Dredd in the main stories really a reformer? I think Wagner’s Dredd in the opening stories of vol. 15 might be described as someone who doesn’t want any reforms at all, but thinks that the status quo needs popular endorsement. He’s positively in favor of there being no freedoms on an individual level, as long as there was a majority vote in favor of that.

– I’m also not sure that Beeny having a career as a superstar performer of humorous songs is really “only in Mega-City One,” seeing that he looks rather as if — in another one of Wagner’s cutting-edge sense of cultural references that appeal to the youth of today! — he is based on George Formby.

– His name is curiously reminiscent of Bennett Bean, but I can’t imagine what the point of that would be.

– Black Widow is perhaps a sign that Wagner was not at his best trying to write for the Megazine’s official remit of an older audience. Because it’s a bit too much an example of its era in that it’s, “Comics can be for adults, and what we actually mean by that is adolescent boys. We’re going to write about SEX here. That’s right, I said SEX. This is grown-up stuff!”

– -Is Hen Broon the first celebrity to have something named after him in Mega-City One who’s a comics character himself?

Although given Formby’s refusal to play racially segregated venues when touring South Africa in 1946, it’s perhaps unfair. His wife, Beryl’s response to Daniel François Malan (architect of apartheid) ringing up to complain about George hugging a black audience member after being given a box of chocolates on stage, ‘Why don’t you piss off, you horrible little man’, is memorable.

David’s comment pushed me to think a bit more about what the George Formby references are doing, and I think they jibe well with what Jared says about Benny being a Nice Guy(tm) if we think less in terms of the actual George Formby and more in terms of his image, especially in the films.

Disclaimer: I have never actually seen a George Formby film — this is all based on online synopses, Wikipedia, and the like. But apparently they were generally the same plot, in which Formby played the same character over and over again, a hapless but nice young man who ends up getting the girl because of his niceness. Classic Nice Guy fantasies. I think it’s possible that Wagner was drawing, perhaps unconsciously, on having seen some of these on television at some point, and that there’s an aspect of America that’s a dark parody of the typical George Formby film.

You know, I’d have said that America was a Judge Dredd story that was certainly about, you know, *America*. God knows it says that it is, over and over again. But the use of an iconic (but horribly dated! I mean, horribly! Good God!) British figure like George Formby, so closely associated with World War II (Am I right in remembering thatv “Frank on his Tank” is specifically referenced) suggests that, yes, this is also about Britishness, and Britain’s relationship with America. I might even go so far as to suggest that Beeny can be read as representing Britain in his desperate desire for America to love him..

Also, Formby punched Hitler in one of his films in 1940, a film that was released in the US and very successful with American audiences. Captain America Comics #1 came out in 1941, Just saying.

Thanks again, gentlemen, for another thought provoking episode.

Interesting that the story which initially garnered the most commentary was “Emerald Isle”. I thought the story was a wretched piece of shit when it first came out and still do. As a Scot (Episcopal, Unionist – the Americans on this site must be wondering why these tribal identities matter so much in the British Isles! Don’t get us started on etiquette!) I have often remarked that the Scots are the only people on Earth who buy the shite we sell to the tourists. The Irish, however, are the only people to appropriate and positively revel in the tropes of the most tragic and torturous aspects of their history (potatoes – the Famine, pigs under the arm – rural poverty, drunkenness, shillelaghs – violence, leprechauns – superstition and illiteracy). By appropriating these tropes do the Irish (particularly those in the South) look at their country through green-tinted glasses and wilfully avoid a truthful and painful discussion about the creation of their country and national identity? Is this what Ennis was commenting on or was he literally “taking the Mick”? I rather think the latter is the case.

I didn’t think “Death Aid” was all that bad. Just a crass satire on Comedy Relief and Children in Need. Until now, I had mistakenly assumed Wagner had written it.

I remember “America” being much lauded at the time but agree with our hosts that it is flawed. I found it interesting that our hosts think that the Dredd strip has been blind to the issue of race and ethnicity (dopey accents and problematic portrayals of Asians and Hispanics aside). Perhaps that is one of the few “successes” of the totalitarian Judges – All citizens, regardless of class, creed and colour, are equally worthless before the Law. A grim prospect, indeed. However, the Judges have failed to create a truly totalitarian state because the rugged individualism of the citizens prevents a volksgemeinschaft from ever existing. Picture a boot stamping on the human face forever. Now picture that human face head-butting the boot back, again and again and again. Nobody wins!