Ugh. I have become snared in, as the scientists call it, “timey-wimey stuff.”

I’m writing this on Saturday to go live on Sunday. A few days ago, on Thursday, Graeme and I recorded Wait, What? Ep. 190, which will be released on Monday, the day after this post goes live. During that podcast, I spent a lot of time recounting my impressions of Jessica Jones, the 13 episode Marvel show currently streaming on Netflix. Graeme, who hadn’t seen it, asked questions and, being Graeme, told me stuff about the show I didn’t know despite the fact I’d seen it and he hadn’t. By the time we were finished, I felt the show had been very thoroughly discussed.

And then I woke up in the middle of the night and realized I’d left out a huge, and kinda important, talking point about the show. And it was lengthy enough I just couldn’t drop into the audio during post-production…although we’re pretty big fans of keeping it organic here at Wait, What? and I can’t really imagine doing more than trimming down my endless stammers and Graeme’s constant tsk-ing.

So, behind the jump, are my additional thoughts about Jessica Jones, the 13 episode show currently streaming on Netflix. If you want to play along with the time travel paradoxes, feel free to read it after Episode 190, so you can experience as it’s intended: as supplemental thoughts to an already existing, yet-to-appear conversation.

(Oh, and full spoilers for the show, by the way! We’re equally indiscreet in talking about it on the show, too.)

So, yeah. Jessica Jones was a really odd experience for me because I ended up watching all the episodes and kinda/sorta enjoyed it despite finding fault with just about everything: Krysten Ritter’s performance was so one-note it became terrible; scenes were infested with genuinely awful writing; the opening credit sequence looked like it was put together for forty bucks during a weekend where the designer also had to help their parents move; the connection to Rosario Dawson’s Claire Temple (whatever Marvel is paying her, they are not paying her enough) was slapdash and unconvincing; the direction was, for the most part, spectacularly lackluster. Even odder for me was seeing a lot of people I follow and respect on Twitter referring to the show was thoroughly excellent, an opinion mirrored in the (admittedly few) media think pieces I checked out afterward.

As I told Graeme, what kept me going was the premise: despite all the “hey, Jessica Jones tried to be a superhero and failed, and now she’s an alcoholic private eye with superpowers” promotion, the vast majority of the show is an ongoing battle between Jessica vs. Killgrave, with an impressive ton of collateral damage as the people around them get dragged into the fight. Ever since my pre-teen days, when I made the jump from comics to Stephen King novels via Salem’s Lot, I’ve always had a soft spot for “regular folks versus a nearly omnipotent evil” stories and I found Jessica Jones the most satisfying when the show figured out new encounters for Jessica and Killgrave, each with a desperate plan to finally triumph over the other.

It also helps that although David Tennant’s Killgrave starts off pretty poorly, with a lot of hollering and gnashing of teeth, the show gives the character—and Tennant’s performance—somewhere to go. (Part of what made Ritter’s performance so awful to me is how the character is just as yell-y, weepy, snarky, shitty and crabby in the last episode as the first, with Ritter delivering her lines exactly the same way all the way through. It’s such unimaginative, nuance-free acting I think less of the directors, writers, and showrunner for not being able to help her modulate it.) And even if the show never develops Killgrave’s power of mind control to Light Yagami levels of complexity, there are still plenty of satisfyingly creepy moments.

So this, I told Graeme, was the great hook for Jessica Jones that kept me coming back despite my annoyance. And then we moved on to other stuff, and the case was closed.

And then I woke up and wanted to kick myself for not even mentioning the other hook, the really important one, the one I think is so strong that a lot of people are giving Jessica Jones a pass a show of similar quality wouldn’t necessarily get.

It’s related to the first hook, which I’d like to say is why I forgot. (But it’s probably not.)

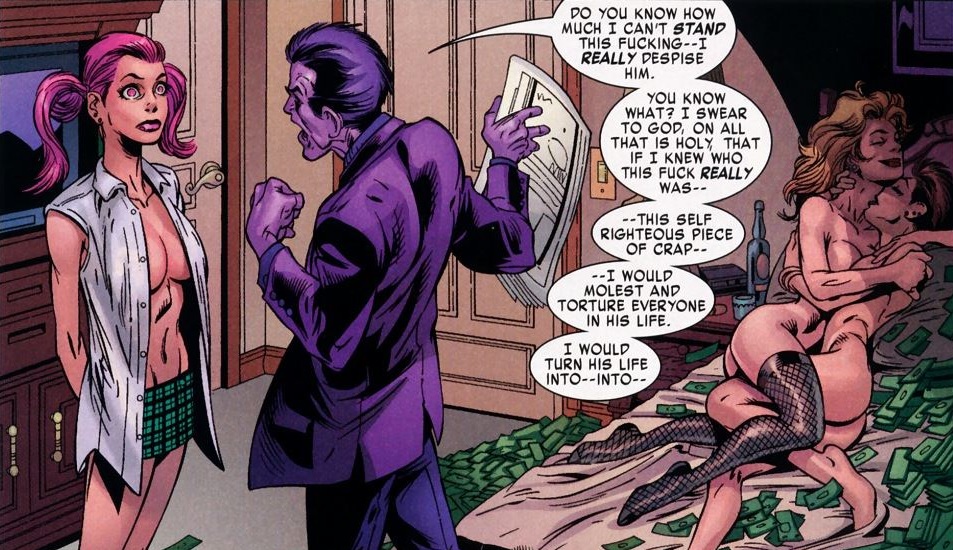

In Killgrave, Jessica Jones has a perfect metaphor for how male privilege leads to violence and sexual abuse and it never loses sight of it. Although I read Alias years and years ago, I don’t remember any of it except that the final Killgrave arc was by far the most satisfying part of the series.

It’s to showrunner Melissa Rosenberg’s considerable credit she saw the what Brian Bendis and Michael Gaydos were doing with that story and developed it to its fullest. The time where Killgrave had Jessica under his control and used her physically, mentally, and emotionally, works as metaphor for rape, it works as a metaphor for abusive relationships, and, in an era where social media allows anonymous men to hunt, hound, objectify, and terrorize women, Killgrave’s horrific acting out of his fixation on Jessica feels perfectly of the moment.

And yet—and this is probably the best part—Jessica, even while victimized, is not a victim. In the first episode, she has the instinct and the opportunity to run but instead she stays and fights. Because she already has her superpowers at the start and the trauma with Killgrave is in the past by the time the show starts, the standard “rape victim gets raped, trains to get the tools to take revenge, takes revenge” arc of exploitation movies (which are by and large male fantasies, even as they channel a need to identify with the women they’re exploiting) is absent. And because Jessica has superpowers, her fight with Killgrave isn’t a cautionary tale, it’s a power fantasy in the best sense and for the best reasons, giving it such a larger opportunity for catharsis: I genuinely believe the show couldn’t have gone to some of its more disturbing places if Jessica didn’t have super powers to keep things from descending into unwatchable bathos.

But also: Killgrave. The show toys a lot with with our empathy by showing us how Killgrave, like a lot of dudes of privilege in this patriarchal society, was made this way and is sometimes unable to tell when his power makes people react the way he wants, as opposed to doing it because they like him. But, like the show, Killgrave also deliberately toys with this idea, usiing it in order to get what he wants, and to repeatedly and continuously deny responsibility for his own actions. Any time he gets a chance to use or exploit his power, he takes it…and it’s usually women and people of color who suffer horribly for it.

Although I acknowledge how this concept is muted by the many parallels the show draws between Killgrave and Carrie Ann Moss’s Jeri Hogarth—another exploitative, potentially sociopathic character—I feel it’s also reinforced by Will Simpson, the only other major white male on the show. Like Killgrave, Simpson is driven to do what he desires (which I guess is why he’s called will?) and, like Killgrave, he kills innocent people of color. White guys destroy. Out of all the many messages in Jessica Jones, this was the one I found most resonant.

That’s what I forgot to say in all the many things I said to Graeme. Rosenberg and her team have crafted a superhero story that works as a way to discuss larger, more relevant issues, while also allowing the viewer to enjoy some satisfying superpowered punch & kick. That’s tremendous. This is why I was so frustrated by all the show’s shoddiness, and especially Ritter’s commited, but unimaginative, performance. It’s not that I wanted to love Jessica Jones and didn’t: it’s that I was loving it….when I wasn’t hating it.

“White guys destroy”? The show’s biggest virtue is that the only white male characters are murderous zealots? Cmon man.

I live in a garbage apartment which I pay for myself with the ~17k I make per year teaching and doing research (I do have benefits though, thank God). It’s super frustrating to read from a person you respect that “white guys destroy,” stated blankly like that. I’m a white guy, haven’t done much destroying AFAIK – what would I even have the power to destroy? – and yet I have to be included in this statement because of my sex and skin color.

Just to clarify, I wholeheartedly support the idea of a show which depicts white people in power abusing their power to the detriment of women and minorities. It’s your phrasing that’s rubbing me wrong here.

#notallpurplemen

Hey, Cass: sorry to frustrate you with the phrasing which is intended, at least in part, to incite. Although I can be super wishy-washy in my writing with far too many qualifiers, I do think there are times were it’s effective to be blunt. I felt to mute that by including a “not all #whiteguys” explanation would be to risk equivocating too much. And considering the way JJ handles Jeri Hogarth, I think a very good case could be made for the show presenting institutionalized power as being an inherently corrupting force.

But my phrasing was what was most personally resonant for me as a white guy. I think of myself as, you know, a good guy but I’m also aware how I have a nice big cushiony blanket of privilege. When I find myself about to chastise an older asian woman for cutting in front of the line at public transit, an action I’m too timid to consider when some jockbro does the same thing? I really appreciated the show having a self-righteous white guy who really is trying to do the right thing but really has no interest in listening to anyone who’s not in a recognized role of authority or power.

And, yeah, there’s a whole other aspect of class inequality that is being overlooked in this country that dramatically warps the tenor of this conversation. Reading this TPM article about the rate at which low status middle-aged white men have been dying in this country was really eye-opening for me.

But, again, as a white guy of my class and status, that was the part that stuck with me from Jessica Jones, even though I still think the majority of people in the world—including the white guys—are good people, who actively go out of their way to hurt or destroy.

So yeah, sorry it stuck in your craw and I hope this clarifies more of my viewpoint. Thanks for the comment!

Thanks, Jeff, for the (as always) well-thought-out elaboration. Fascinating link too (although idk if you saw the update, upon further inspection, the data seemed to apply more to white women than white men, which while not negating his theory does fuzzy things up a bit). I’ll admit to being pretty sensitive from personal experience about the use of “white” or “white male” alone as a general marker of unchecked privilege. My close relatives are some of the people under discussion in that study you linked to. If they had special white privilege, it was certainly negated by growing up poor with inadequate education.

Oh, man. Thank you, thank you, thank you for putting this (as always) so eloquently. I’ve been trying to put into words what I liked about this show, and why I liked this show, despite everything I would say about it sounding like a complaint.

Noah Berlatsky has a pretty solid piece on this, that may be of interest:

http://qz.com/559803/in-jessica-jones-marvel-takes-on-the-biggest-villain-of-them-all-the-patriarchy/

Thanks for this, RF! I saw Noah talking about this online but I hadn’t finished watching the show at the time. Looking forward to clicking through!

Response to what you write here in this article and what you guys said on the podcast:

I don’t terribly disagree with what either of you said… but I think I liked the show more than either of you did… but also have other criticism(s)… not that my criticism(s) is even on the level of something “bad”.

While mainlining all 13 episodes in about three days, I felt that it was a fairly well-made show with a lot of great ideas and drama centered around Killgrave, but I felt like there was something holding me back from outright loving this show the way I loved “Daredevil”… And then around episode 8 or so it suddenly hit me like a ton of bricks that “Oh, that’s why I’m not super in love with this and feel like something’s nagging me: The lead character is unlikable, dour, and annoying.” I feel that this obvious aspect was missed in most reviews, and I didn’t consciously register it until several episodes in, but it’s kind of a major factor: The Jessica Jones we see here is basically an inherently unlikable person.

Unlike you guys, I *don’t* think this unlikability is down to Ritter’s acting. I think it’s basically a result of the script and the directing as well. More than that, I think what we’re perceiving as “unlikability” is not so much of an accident but is intentional (though perhaps not “super-intentional”) on the part of everyone involved. They want her to be this way. And lest anyone else get the suspicion that “Oh of course some white guys aren’t going to like strong female awesome bitch Jessica”, I’ve seen multiple feminist bloggers point to Jessica’s “flawed” nature. And, while they’re certainly not complaining, they don’t unabashedly like it either. Even if they outright love the show overall, it’s still like “Yeah… Jessica herself is… difficult.”

The sort of catch-22 is that the reason why she’s unlikable is connected to the central problem that she’s overcoming: Extremely bad stuff happened to her, and it’s not really her fault at all (unless you want to blame a child for arguing with a sibling in the back seat of a car — which doesn’t seem fair, at all). Jessica has been through a lot, has been treated horribly, and has already blamed herself infinitely more than she should for things that she shouldn’t blame herself for at all. This is obviously why she’s in such a bad mood all the time, and it’s understandable (just not infinitely great to watch or to present as art). This is why there’s the central struggle of the character, to overcome her demons and work toward a better life in which she finds value for herself by giving value to others. At the same time… because that’s the setup… in the meantime she is virtually unlikable.

I mean, I liked the show quite a bit overall. I liked the storyline. I cared about the characters. I was caught up in it. I thought the action was handled well. I watched like 4-5 episodes a day. I liked it! And I don’t think the show or the characters could be tweaked just a little bit in order to improve it. I think it’s as good as it could be in anything remotely resembling this configuration of show. It’s good BECAUSE of the central character flaw. Remove that character flaw, or tone it down, and so much of the surrounding dramatics lose their impact. But, still, yeah, for all that, you have to put up with a protagonist who is unlikable and annoying and almost pointlessly depressing. The fact that she’s pointlessly depressed and pointlessly hard on herself… is the point. :-/

But it’s too the point where Jessica Jones needs to mutter “breeders” as she pushes women with baby carriages out of the way. It’s like… does that really need to be in there? It’s another touch of ugliness in her character. (And I’m saying that as someone who in general does not like babies.)

I also want to comment on the “anti-white male” stuff. Overall, up front and at the risk of sounding hopelessly cliche: I liked the diversity of the cast and as a white male I was not offended.

That said, the show is basically hard on every single character (and type of character) that it introduces — with virtually every new character being treated with either suspicion, contempt, or annoyance — but, actually, yeah, this is particularly true when it comes to white male characters. It’s just there. On the one hand, you have to hunt hard to find ANY characters in this show that are shown in an overall positive light… At best, almost anyone can hope for is that they’re shown in shades of gray… But there are NO white male characters that are given that concession.

Killgrave is obviously a bad person. The white guy upstairs is an awkward loser pervert about whom the best we can say is that he didn’t deserve to be brutally murdered. “Nuke” is ultimately revealed as a monster, and Patsy is shown to be wrong for ever having given him the benefit of the doubt (“Message to women: Don’t ever give a white guy the benefit of the doubt”?). Even the white guy in the Killgrave Victim Support Group just happens to be the one person whose grievance is laughable, because all that happened to him was that he got his coat stolen (“Message: White guys can make no legitimate complaints, ever, and can never identify themselves as victims of anything ever”?). Even the white male nurse in one of the last episodes: he gets yelled at and treated as an incompetent by the black female doctor because he can’t prick Luke’s skin with a needle. After this happened, and the doctor finally realized it was because Luke’s skin was unbreakable, I half expected her to call the nurse back in and say “Hey, sorry, it wasn’t your fault”, almost as a meta message to white male viewers “We know you all aren’t either evil or petty or idiotic”. I would have loved that. But there was nothing like that.

I’m not really complaining about any of this. And, for example, it should be perfectly well understood that there were plenty of FAKE Killgrave “victims” with stories that were more idiotic than the one white guy who was barely a victim. There were also female characters who were dubious to say the least: Carrie-Anne Moss’s character, who was probably the second most heartless character in the show, as well as Trish’s mother, to name just two.

But I still feel like the show definitely had a repeated pattern of unapologetically showing white guys in a bad light. And I’m okay with that! It doesn’t make me hate the show or feel insulted. But it is there. I’m okay with it even though I know that if even one of these scenes had the races and/or genders reversed, then it would send Twitter into a frenzy. “Jessica Jones was great… until that last episode when the white male doctor treated that black female nurse so horribly!!!” Of course, for decades our popular culture did have many examples of white male characters casually dismissing and insulting female characters and characters of color. So, we’ve done that, and it was terrible. And at this point complaining about Jessica Jones treatment of white male characters would seem laughable, especially sense, oh yeah, virtually every other super hero property out there is pro-white male. (So, should we get to a point in society in which we’re all so equal that Jessica Jones can be looked back on as racist and sexist against white dudes? Would that mean that real progress had been made, if this show could be criticized in that way? I think about this for a second, but then it’s like… Personally I don’t even care.)

Something about it all still seems weird to me. Not bad, but weird. I think I just feel that the show at times verges on a strange female wish-fulfillment that isn’t really thought through or pulled off well enough. Or, even if it is, then I’m not sure what it says. I think whatever strangeness there was, all the way back in Alias #1, which Bendis got grief over, in the portrayal of Luke Cage doing it doggystyle, is there there. I almost feel like Luke Cage is there for Jessica to use him, almost as a way of the female to say “I can be as bitchy as I want, and this guy will still love me. I can screw up however — even to the point of contributing to the guy’s wife’s death — and this big athletic man will still love me and give me awesome sex.” There’s something strange about it, and I’m not calling it racist, but I do feel like Luke wasn’t *humanized* enough or something. I feel like the character was used to represent this… ideal, or something, which is strange since in another way he’s supposed to be this street-level character. And I generally liked Luke Cage in this, but I feel like the character was USED, in a limiting way.

I think it all goes back to Jessica’s unlikability, because why the heck would Luke already want to be SOOO into this woman who is so angry and screwed up and willfully miserable? It seems like female wish fulfillment, which would be fine but it just isn’t… handled all that well or something.

Probably someone will be offended by all that. All I can really say is that none of the above bothered me, per se, but I just felt like there were ALL these themes swirling around under the surface, and the show didn’t really deal with them well enough. Or deal with them much at all, and even when it attempted to deal with race once or twice (Luke saying “Is this a black thing?” or the white perv neighbor saying “They say we’re all a little racist”), it almost came off as if the writers were hanging the issue on a lamppost as if to say “Yeah, we think if we can just casually/jokingly refer to the issue in an awkward way, then that’ll be good enough and we can say we’ve dealt with it.” But, no, they didn’t. I’m not sure anyone could, though. At most what I can say is that despite some of my ambivalence, it’s all so INTERESTING, and that’s a big part of the reason why I liked the show overall.

Wow sorry for length and the 3-4 typos. :-/

I’m glad you spent a little time talking about why the show worked for you; I felt like Graeme’s extremely negative reaction pushed you into focusing only on the parts you disliked, but I thought the successful parts of this show (mostly outlined here) were far more interesting than its flaws.

Contrary to Jensen (and you, I guess), I didn’t think the show had a pattern of showing white guys in a bad light, mostly because two characters and a handful of supporting cast members in tiny cameos don’t make much of a pattern. I mean, yeah, Killgrave is a monster of male entitlement and Simpson shows how another, seemingly more dutiful and noble kind of masculine authority can easily turn toxic, but it strikes me that you can accept both of those things as true without inferring a blanket statement. I’m not going to say the show makes that statement just because that one doctor didn’t apologize to that one nurse…?

I think what the show does instead is decenter and marginalize the white guys who have been at the center of pretty much every other superhero movie and TV show (and most of the comics), pushing them to the edges of a story so female-centered that even the female supporting cast members have their own female supporting cast members. I doubt this was the first superhero movie or TV show to pass the Bechdel test, but it feels like the first one where those interactions actually meant something.

And you know, it’s a pretty limited experiment. Even the Netflix corner of the MCU, as diverse as these things have ever been, is still half populated by white male protagonists. One series will focus on Iron Fist, the white guy who gets raised by some magical Asian monks who teach him how to do kung fu better than they do. I think we’ll all survive one show that pushes the white guys off to the side, even suggests that Simpson’s brand of heroic masculinity is potentially just as dangerous as Killgrave’s more overtly predatory model.

But to reduce that to “white guys destroy” isn’t just an incitement or a disservice to listeners like Cass. It’s also a disservice to the series, which is doing something much subtler in its handling of its cast. This is a series that goes out of its way to show that people don’t need Killgrave’s powers to manipulate and control each other, and they don’t need Simpson’s background and training to go on a self-destructive quest to make themselves into a hero (but the meds help). The women make the same mistakes the men do. Some of them pull back and some of them don’t and some of them just don’t have the power to make them quite as badly, but that gets lost when you try to turn the show into an exercise in proving your counter-hegemonic bona fides via a little self-flagellation. It’s really, really not always about us.

Thank you so much, Jeff, for putting this into words. I was unable to pinpoint exactly the reason why the quality of the show seemed to be less of an issue than how IMPORTANT it was.

And also, your statements referencing the concept of Killgrave’s privilege made me think of recent conversations I’ve had about entitlement. His desire to play the victim while at the same time subjugating others (explicitly or implicitly), and (even more common) his blindness to his own privilege: the “born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple” argument.

Obviously, Killgraves megalomania is an extreme version of it, but you see how much rage he shows when he doesn’t get what he wants, and it makes the show’s ending (which didn’t make a lot of logical sense) make more thematic sense.

SPOILERS

.

.

.

.

Logically, as Killgrave even points out, she should have jumped over the people, killed him, and then worried about the people afterward–separating them and waiting for his effects to wear off. There would have been collateral losses, but Trish wouldn’t have been put in danger and Killgrave wouldn’t have been able to do any more damage.

But this ending allows Jessica to play off of Killgrave’s entitlement and use it to her advantage. It allows her to use his almost primal need to be the one in power–the one in control–to employ her own brand of manipulation. And, of course, to pay off the “I love you” gag.

Thematically, just leaping over to him and putting a fist through his head wouldn’t have had that payoff. Strangely enough, it would have been MORE anticlimactic than the anticlimax that we got.