Previously on Drokk!: Technically, last episode we took a detour on the read-through of all the Complete Case Files to dip into the Restricted Case Files and look at Judge Dredd stories from outside the main 2000 AD series, but really: We’re up to the tenth year of Dredd, and Mega-City One is now pretty much a hellish dystopia and the Judges are as trapped by the system as those they’re technically protecting. That’s all you really need to know.

0:00:00-0:08:26: We introduce ourselves and the fact that we’re reading Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 10, which covers 2000 AD Prog’s 474-522, from 1986 and 1987, and then we almost immediately derail ourselves by talking about the fact that this collection offers a coherent deconstruction of Dredd and his world despite the fact that it wasn’t originally intended to be collected. Were writers John Wagner and Alan Grant just looking for an excuse to redefine Dredd, or trying to keep themselves interested?

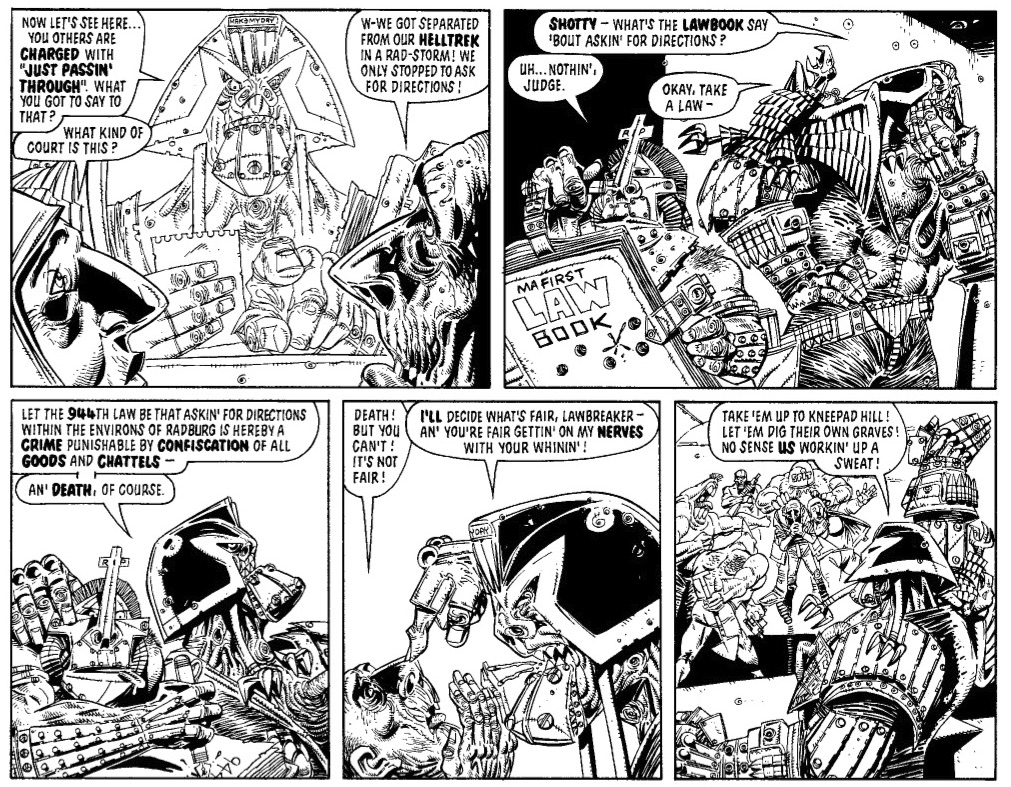

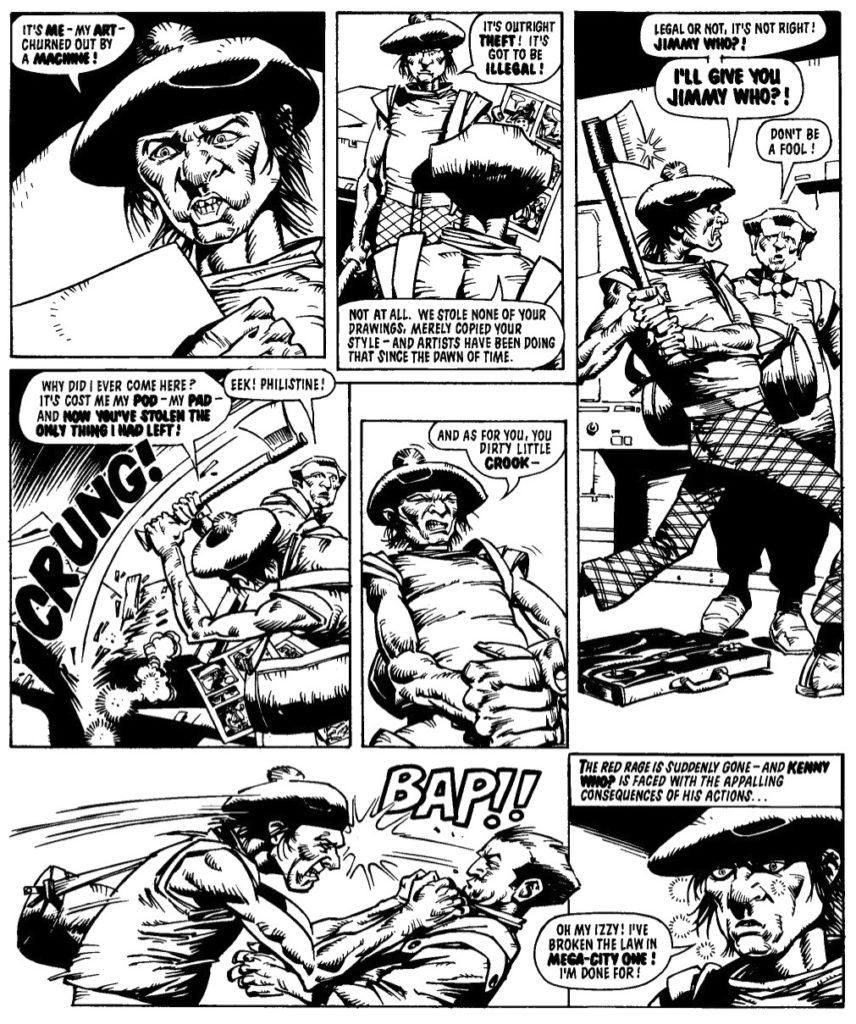

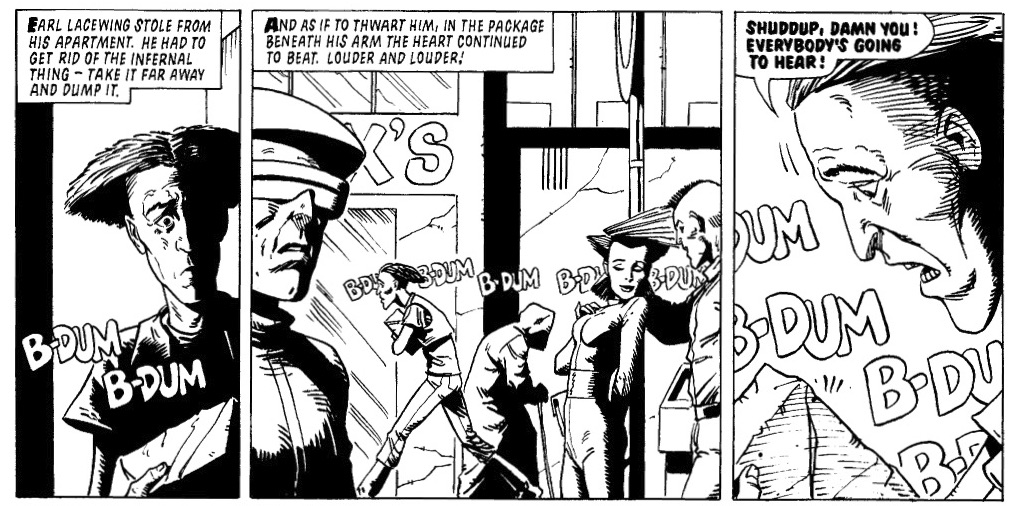

0:08:27-0:22:28: Is the idea of being a success in the comics industry the cruelest joke ever told in Judge Dredd? We talk about “The Art of Kenny Who?” and what it says about the strip’s relationship with comedy and authority. We also talk about the impossibly strong opening to this book, the influence of both EC Comics and Kafka, and what the strip is actually about at this point in its existence.

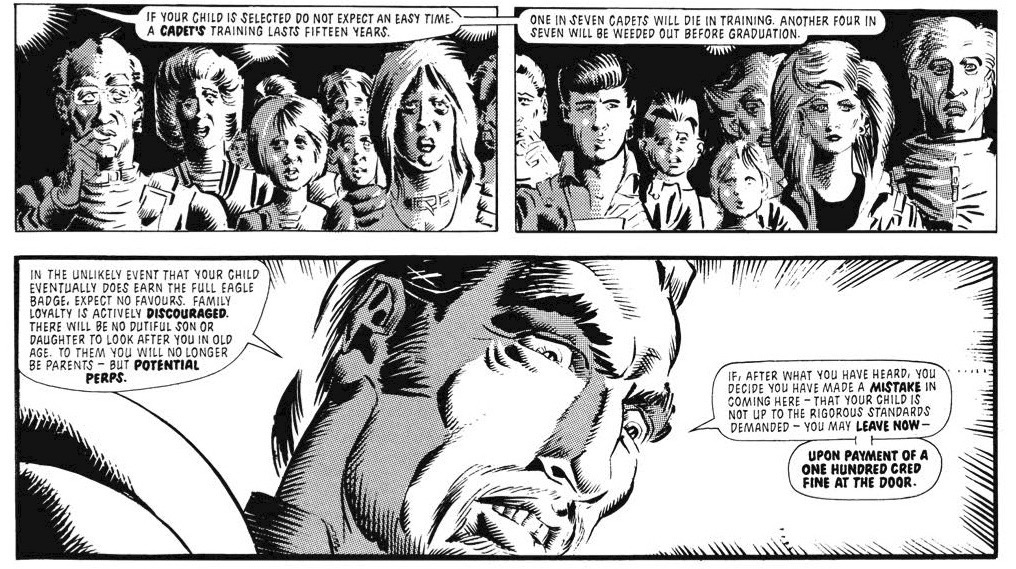

0:22:29-0:47:28: Is Judge Dredd a bully? Well, yes, but this volume really seems to be determined to demonstrate that, to the point where it’s difficult to see Dredd as anything but. We talk about that, as well as how cruel the character has become, and how slowly that change has been. (Also, has the character changed? Jeff thinks it might be that the creators have changed, instead, which is an interesting point of view.) Also, because it’s Dredd from the 1980s, racism rears its ugly head in “The Fists of Stan Lee,” and we get into the fact that this is very clearly an era of the strip where Wagner and Grant are lifting directly from whatever they’re watching, listening to, and so on.

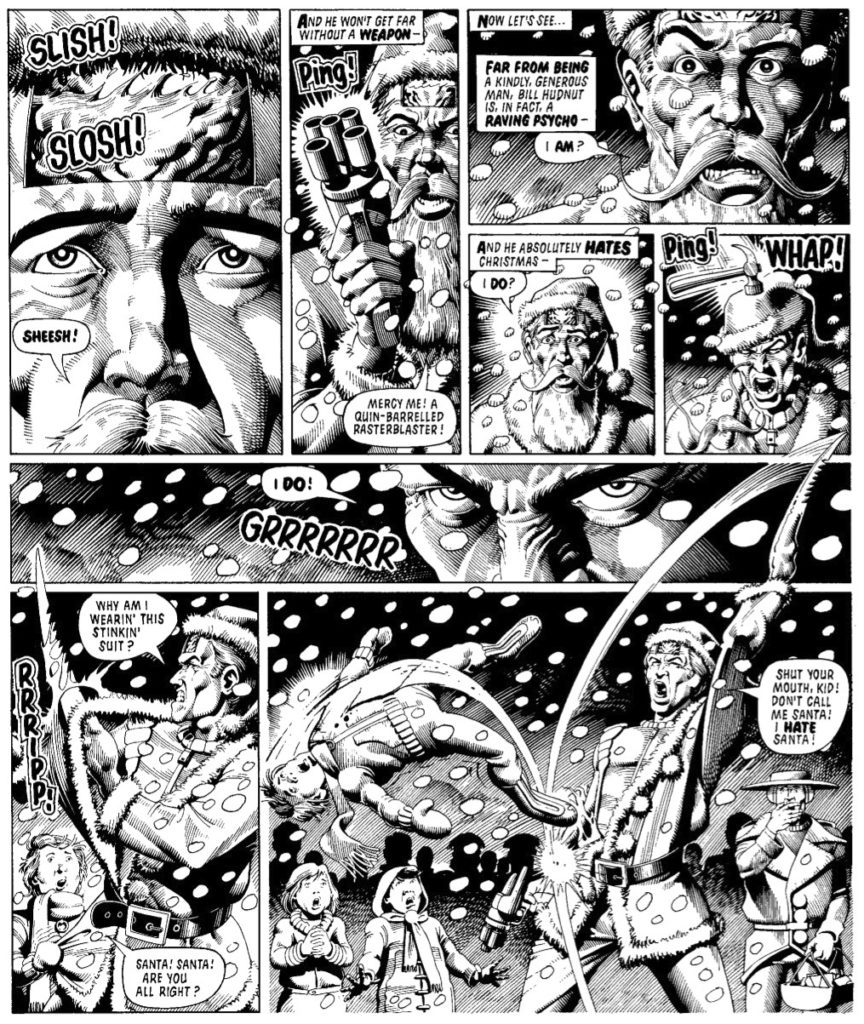

0:47:29-0:59:14: Jeff, bless him, thinks that I managed to time this volume to this month because of the very strange Christmas episode in the book. I didn’t, and I’m not as taken by the story as he is, but we talk about whether or not it’s a wink to the audience that everything’s fine, really, or a sign that things are worse than they seem. My need for narrative closure shows up, and Jeff is a prince amongst men for not making fun of me for it.

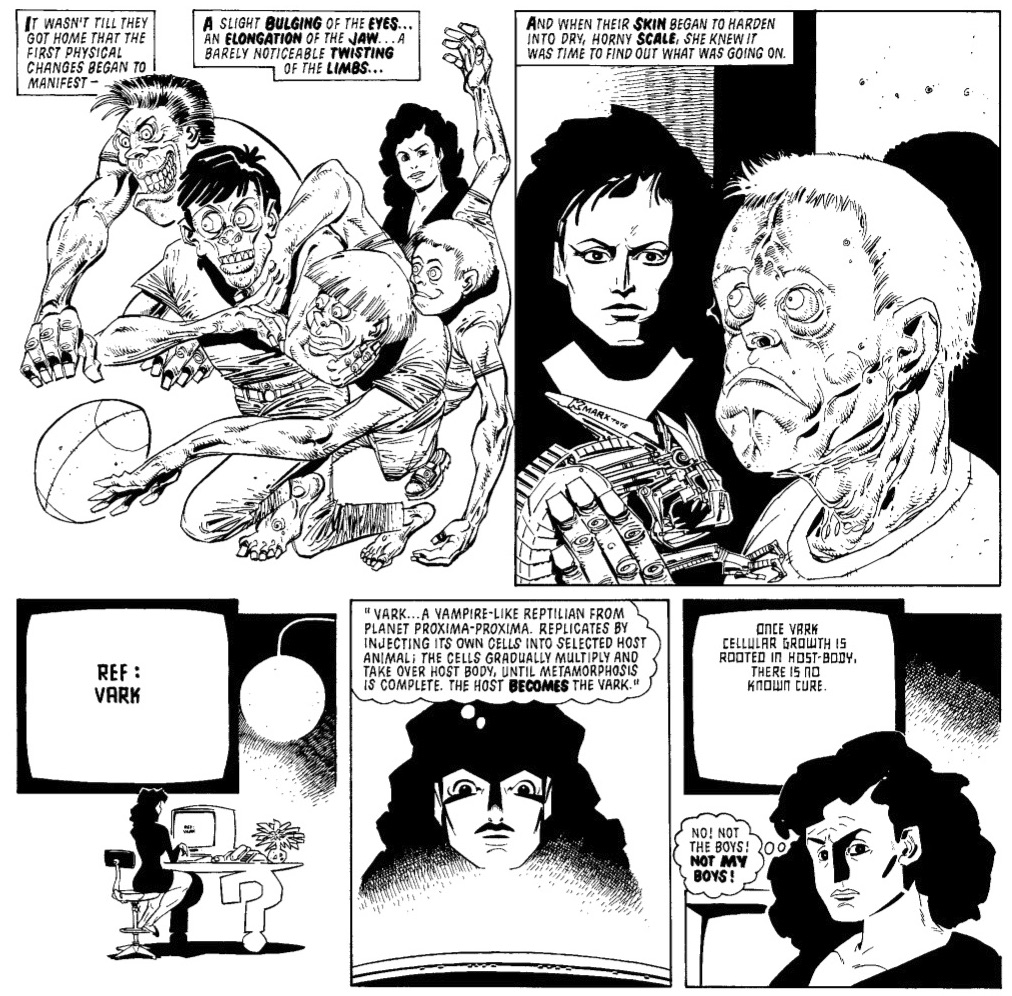

0:59:15-1:26:57: We speed through another few stories in the volume, touching on the greatness that is the name “Slick Dickens,” Jeff’s being creeped out by Kevin O’Neill art (and my sharing a possibly apocryphal story about Kevin O’Neill and the Comics Code Authority), and the greatness that is Brendan McCarthy’s artwork on “Atlantis,” a storyline which Jeff compares to Jim Thompson, of all people. We also talk about about Jack the Ripper and Michael Jackson, or at least the versions of them that re-appear in this volume in a way that may or may not be connected. All this, and Harlan Ellison, too!

1:26:58-1:39:11: Finishing off going through stories, we touch on a few more, and talk about the brutality and rejection of nostalgia present in this book, even as the strip celebrates its 10th anniversary. Jeff talks about what might be his favorite moment in the book, while I share what I think is the most important line in the entire volume, and we end up talking about how prescient the series is in its approach to certain topics, even if that seemed like science fiction three decades earlier. Is this the British version of Jack Kirby’s OMAC in that respect…?

1:39:12-2:02:34: We wind down by talking about just how much we love this book (Spoilers: a lot), and the level of craft that Wagner (and Grant) have maintained for almost a decade at this point, and the complexity of tone and content that we’ve just come to accept and expect from Judge Dredd as a strip without really thinking about it. We also talk briefly about yet another short serial in this volume, this time one that I’m a big fan of while Jeff is far cooler. Basically, though, these are comics done right and we want to see more of this if possible. (There are many more volumes, so it’s pretty possible, really.)

2:02:35-end: As the end approaches, we swiftly wrap everything up by mentioning the Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and Patreon, while somehow failing to wish you all a happy Christmas and Hannukkah if you celebrate either What were we thinking? As always, thank you for listening and reading; we’ll have a year-end episode next week, but until then, I’ll do it here: Happy Holidays, Whatnauts.

Scattered thoughts:-

-Quick note: if I’m remembering correctly, What If The Ads Were Written By The Judges is the strange silly thing that it is because it was part of the 10th anniversary celebration. So it should be read as something that appeared alongside 10 Years On as a palate-cleanser. Although obviously now that the ads it parodies are a distant memory, it’s not going to have much impact. But it was an amusing bit of fluff at the time.

-Our hosts are probably right that this volume as a whole wouldn’t be a good introduction to Judge Dredd. But I think I would put “Paid in Full” in a Judge Dredd sampler collection as a good introduction to Judge Dredd in its absurd/satire mode. The idea of a “biller” is so brilliant and funny that I almost wish it hadn’t been used as the basis of its own story, but thrown into a different story as one of those insane details about life in Mega-City One. Then again, the brilliant way that Wagner and Grant spin out the absurdity of the premise is just so good that in the end I can’t resist this one.

(Also: See! See! This is what happens to people who think that supernatural stories have no place in Judge Dredd.)

-Great discussion by our hosts of The Law According to Judge Dredd. Very true that it is, in an important way, about Wagner’s own doubts about the monster that he has created – what at this point he probably realized would be the first thing mentioned in his obituary.

And that’s another thing – this is the product of a perception that Judge Dredd is something that will mean that John Wagner will probably get an obituary, at least in the local paper, but very possibly in the national broadsheets. (At the same time as Wagner is all too aware that he won’t see much actual *money* from that.) TLATJD is about Dredd as a national *institution,* something more than the disposable throwaway character for a disposable throwaway medium that he was created as: “Creep was right about one thing. There is only one Judge Dredd. Wasn’t him, though.”

For the first time, Dredd is aware of his own mythic status as more than an ordinary character. One can trace this dual emphasis on critiquing Dredd with celebrating his success as an iconic figure elsewhere in the volume. Ten Years On is obvious. More interesting, in a terrifying way is the idea of the “Dredd Syndrome.”

I think there’s an assumption here that Wagner and Grant are writing for an audience that has (to a certain extent) grown up with the comic. . I think our hosts made some sharp observations about how the mad mutant “Judge Dredd” is essentially an entitled fan. More generally, this reflects, obviously, the “Comics can be for grown-ups!” era of the mid-80s – not to mention the awareness of things being put into collections as a possibility about which our hosts commented.

But I think there’s also an aspect of the atmosphere of the time. Thatcher seemed at this point inescapably dominant. Scandal hit the government around this time (the whole Westland thing, which is relevant to Dredd in that it was, among other things, about Britain’s relationship to America). But no-one thought that Thatcher would be going anywhere because of it. Dredd too becomes an inescapable figure who is larger than the ordinary – you can critique him, but you can’t escape him.

-But there are, as our hosts, noted shifts, things the previous Dredd would never say. And at least one thing that he never before would have done, when he makes someone “peep for the city.” It is antithetical to how Dredd had behaved up to now that he would *ever* let someone escape punishment for a crime in return for accepting employment in this way. This story takes a big step towards depicting Mega-City One as an actual totalitarianism.

-I’ll push back against our hosts a little on the rich person saying that because he was rich he had a right to live. I don’t think that’s something where we now live in a different world than the world of 1986-7. Or more exactly, I think that we live in the world that the 1980s made, and it was already noticed, commented on — and satirized — at the time as it was coming into being. Concretely, consider e.g. Thatcher’s promotion of, and personal use of, Bupa in preference to the NHS as the sort of 1980s issue to which this sort of satirical exaggeration was relevant.

I can think of parallels elsewhere in British media at the time. There was a sitcom (admittedly dismally unfunny, but it illustrates the point) whose premise was to extend the t ends of the Thatcher era into an imagined future where the North of England was a dystopian hellhole, and the South monopolized all the prosperity, but literally everything had been privatized. As I said, it was terribly written, but that line would have fit right in.

Another scattered thought:-

-I’ve suggested that you can over the last couple of volumes see W&G respond to how the public perception of comics and their readership was changing, and specifically to the British Invasion. Kenny Who? is obviously the first story built directly around commentary on the possibility of a British creator working for American publishers.

One has to observe that there’s a basic falseness to it. Online information suggests that the point of this was to satirize British publishers’ refusal to pay royalties, but on the page, this reads as an attack on specifically American practices. W&G end up peddling the 2000 AD reader a fantasy that 2000 AD isn’t like DC & Marvel, when it was, in fact, even worse. That’s not so good.

But otherwise this is fabulous. I can even almost forgive the problem in the above paragraph, because Kenny Who?’s Americanness isn’t insignificant: this is W&G’s version of a classic American story – the young man who goes to the city to make it big and has his dreams crushed by the operations of US capitalism.

Note Judge “Hammer,” a nice little touch that adds to the American of it all — and note also the *absence* of a comedy accent for Kenny, who is positioned as “normal” in contrast to Mega-City One as the alien environment. It is not, after all, as if Wagner and Grant had any objection to doing comedy Scottish accents (see McNulty, Middenface).

More interesting still is the parody of Midnight Surfer, with the whole city knowing Kenny’s name, just as they knew Chopper’s, but it’s “Who?” and it’s not his any more. As Kenny says, they even stole that. If both of Chopper’s stories have been about how you can always beat the machine, even when you lose, this is the story that says, “No, the machine *always* wins.” There’s no way to create one’s own identity that they can’t mush up and replicate. Individuality is just another product.

And the final touch is that Judge Dredd rubs it in that Kenny has lost, as our hosts point out.

More scattered thoughts:-

-As I tried to suggest above, The Art of Kenny Who? locates Mega-City One as distinctly American in a way that has tended to fade (although it’s never been completely gone) since the strip’s earliest years. Something that connects to that is an interesting dog that hasn’t barked, until now.

We are now in our tenth year, and for the first time we are seeing Brit-Cit judges, despite the fact that one of the most obvious things one might expect a British strip to do is to show where Britain fits into its imagined future. And even then, we’re not seeing British judges in Brit-Cit, (Somewhat surprisingly, we’re going to get Dredd visiting both Australia and Ireland before he visits the country in which the comic is being created and where the large majority of its customers live.)

To some extent, this is because Brit-Cit did feature in Robo-Hunter, but the exact relationship between that Brit-Cit and Judge Dredd’s Brit-Cit was vague at best. (2000AD was not really about a coherent shared universe. I mean, you could say that pretty much everything was in the same universe if you used people drinking Mac Mac as the criterion, but there was no attempt to make the pieces fit together.)

So I don’t think “Because Sam Slade” is a complete answer to the questions, why haven’t we seen British elements before, and why *are* we seeing them now?

One thing that adds to how puzzling those questions are is that when Judge Gomery does appear, he’s completely surplus to requirements. There’s no reason why Atlantis couldn’t be a solely Mega-City One colony. Leaving that aside, the story has no interest in what Brit-Cit judges are like and how they might be different from the judges that we know. Gomery as an individual character plays no necessary role in the plot, and he receives nothing that one could really call “characterization.”

So it’s absolutely not a matter of this particular story needing to go there. But it does stick – thanks to lingering jet lag, I couldn’t sleep on Christmas Eve and mainlined the whole of the next volume, and people from Brit-Cit continue to appear. So there’s something going on here.

What is it? I really don’t know, but I’ll hazard a partial guess. For the first question (why avoid Brit-Cit for so many years?), I can see that bringing British elements in disrupts the delicate balance in which Mega-City One is in a future America entirely to the extent that it needs to be for a particular story. The moment it’s in the same world as a future Britain, that’s it: Mega-City One is America.

But why should that change now? One possibility is that it’s connected with the dystopian turn, that as Dredd becomes less of a traditional boy’s action hero and more of an explicit representative of a horrific totalitarian state, it becomes more attractive to define him more clearly as American — not the America-as-seen-through-the-lens-of-slightly-jealous-British consumption-of-American-media that Dredd started as, but a more realistically depicted not-too-far-future authoritarianism that satirizes Reagan’s language — pervasive in the ‘80s — about America as a beacon of freedom. We are, after all, not too far off from the point at which Wagner will try to make his big statement about all that in a story called, well, “America.”

But there’s also something bubbling in there about Britain, and (you guessed it) Thatcherism. And Europe, because everything is about Brexit.

This was about the time that the Westland affair dominated the headlines. And what that was about was bringing to the forefront how Europe had come to be an issue that split the Conservative Party – the beginnings of a long process that culminated a very short time ago with Johnson’s subtle tactic of kicking all the pro-Europeans out of the parliamentary party. Back in the mid-80s, though, the Conservative Party had quite recently been easily identifiable as the more European of the two parties that mattered. Thatcher had originally campaigned in favour of British entry to the EEC. Labour had included British withdrawal from it in their 1983 manifesto.

At the time when these comics came out Labour’s steady move to the right in search of electoral victory was starting to reverse the relationship between the two major parties on this issue. The other side of the coin was Thatcher’s personal, and the Thatcherite right’s, simultaneous movement in the opposite direction. For a Tory, pro-European now was coming to equal wet.

So, what does that have to do with America? Essentially, it’s that Thatcherism came to equate making Britain more like (a right-wing idealized view of) America with distancing Britain from continental Europe. Westland was perfectly suited to crystallize that, because it was Thatcher seeking to give Westland to an American company in opposition to Heseltine’s desire to give it to European companies – and because it was about national defence, it pushed some deep-seated buttons about identity at the same time.

Coming back to Dredd, the intrusion of Brit-Cit is not *directly* about any of that, of course. But I’d double-down in saying that Dredd can be about America, but never really about America – it’s about ideas and uses of America in British culture and what that says about Britishness in the postwar era. And Mega-City One becoming at the same time more clearly defined as American and also as a dystopian tyranny does on some deep level reflect shifts in the role of America in the British imagination that were separately playing out in the political sphere in a different way.

Look, bear in mind that for contemporary relevance I *could* have been mining the Chicken Song…

-Can’t say I care for the unimaginative design of the Brit-Cit judge uniform. The design that Games Workshop came up with for the roleplaying game was better.

Weird, because McCarthy normally is distinctly inventive about character appearances. Not always in a well-advised way, as seen in The Witness. The dolled-up miniskirted female judge, whom the script seems to want to be a forensic investigator but whom McCarthy depicts with rather blatant sexism as a secretary — no, that’s not good

-To be fair, as our hosts noted, McCarthy is the best thing about The Witness. At the time it struck me as a remarkably flat and routine story to do for the big milestone issue #500, and still does. Nowadays, I have to wonder if there was an element of protest to that — W&G deliberately doing something bland, just another Dredd story, that doesn’t celebrate 2000AD, precisely because of how little the publishers were repaying them for doing so much to get this crap little comic that no-one expected would survive to 500 issues and increasingly, to a measure of mainstream recognition and even respect.

-It’s fun to see Cam Kennedy draw in a reference to Tom Veitch. Were they discussing working together this early? It’s the first time, I think, that one of the minor celebrities after which something in MC1 is named is drawn from the world of comics themselves.

Just to point of a bit of trivia about Ellison’s “The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World.” It’s a follow-up to Robert Bloch’s story “A Toy for Juliette” which precedes it in Dangerous Visions.

And Bloch’s “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper,” which started the whole Jack-the-Ripper-as-sci fi trope, is a much closer match to (Bloch’s) “Wolf in the Fold” than Ellison’s story. Bloch, it seems to me, was ripping off himself, not Ellison.

Doug–my *huge* apologies for this comment being in limbo so long! I’d meant to log in sooner and check to make sure no comments were stuck and clearly waited wayyyyy too long.

That said, “Yours Truly, Jack The Ripper” is barely sci-fi, isn’t it? Apart from the whole “it’s modern day and here’s Jack The Ripper” angle? (My memories are very, very hazy: I don’t know if I read a lot of Bloch, but I certainly read more than my share.) But that said, I very much think you’re right in that Bloch was the one who really got the engine revving on the JTR-but-still-now kind of way that hit a certain amount of success in the ’60s and ’70s…

Not much to add to what you and Voord have said, only another somewhat obsessive art credit query: I suspect the late Steve Whitaker inked the second part of ‘The Witness’ as well as the first, although he’s only credited on the second. It’s probably easiest to see the difference in style between McCarthy inked by himself and inked by Whitaker if you look at the faces of Dredd in ‘Atlantis’ and in this story. McCarthy’s own ink line is more organic and Steve’s is more stylised. McCarthy would have the skill to ink in a different way to maintain the look of a piece, but I can’t quite see him bothering.