Previously on Drokk!: The mega-epic “Oz” changed Judge Dredd forever by bringing about an end to the John Wagner/Alan Grant writing partnership on the strip, and setting up a brave new world where Dredd really dislikes a guy called Jug Mackenzie. I mean, that last bit at least feels very realistic.

0:00:00-0:02:16: After what might be the best cold open any episode of Drokk! has seen or will ever see — I’m not going to explain the context, for fear of ruining it — we quickly introduce ourselves and the fact that we’re talking about Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 12, which features material from 2000 AD progs 571-618, from 1988 and 1989.

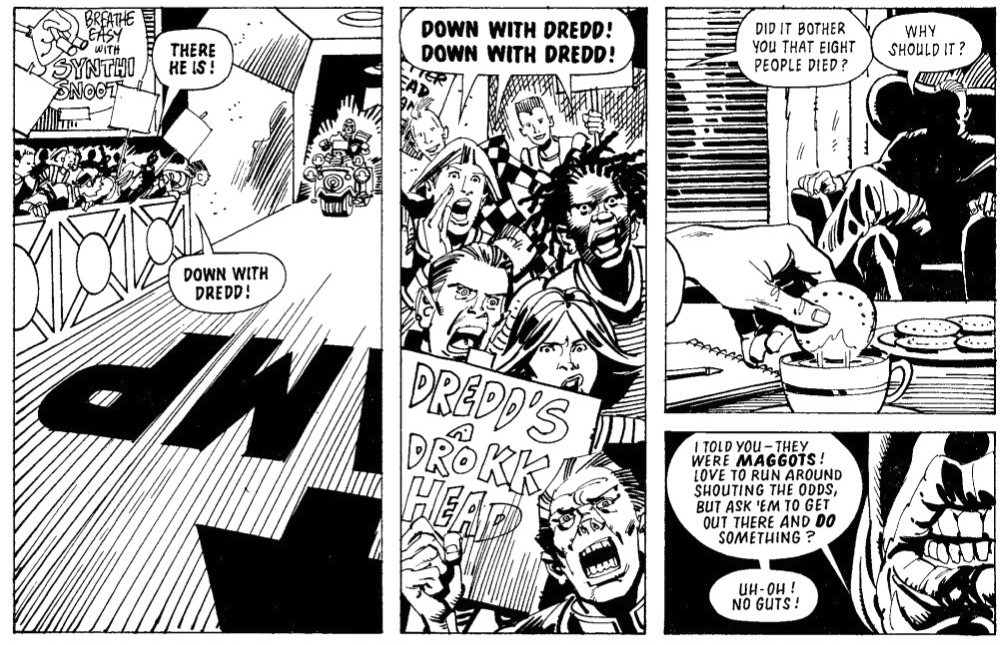

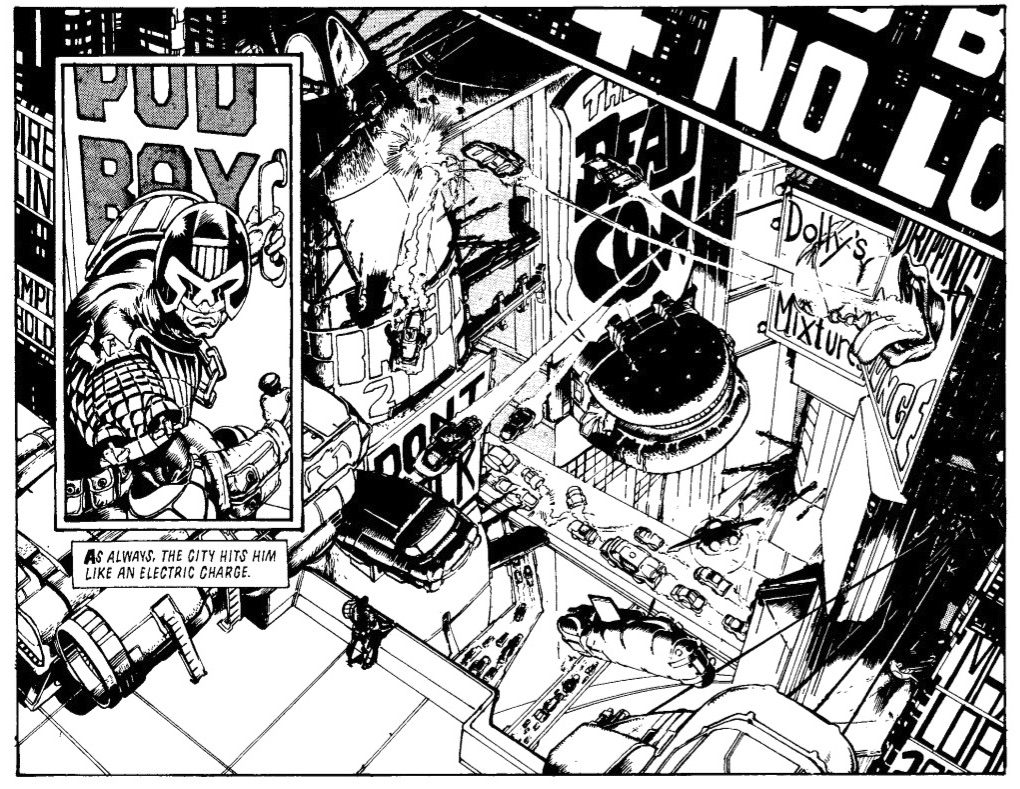

0:02:17-0:25:07: It’s a strange volume, and that makes for a strange episode, to be honest; we start by talking about the ways in which the stories in this episode aren’t what we might have expected, judging by the evolution of the strip, which includes Jeff calling this volume Will Elder instead of Will Eisner; I bring up what I see as John Wagner’s new direction for the series, debuting in this volume — with Dredd getting older and starting to have doubts in himself, if not the entire system — and we get to talking about whether or not that feels out of character, before talking about the difference between John Wagner’s stories and Alan Grant’s stories, as seen here.

0:25:08-0:31:19: Is there a theme of writing about mental illness in this volume? We talk about the possibility, as well as couching the discussion in the fact that it would be mental illness as viewed through the same lens as the way the strip at this point deals with race — which is to say, very clumsily and embarrassingly indeed.

0:31:20-0:43:09: Returning to the subject of the disappointment of the volume as a whole — Jeff describes it as “an exercise in delayed gratification,” which is fitting — there’s a suggestion that one running theme is that of chaos, which shows itself both in the narratives themselves and the ways in which Wagner and Grant structure the series. We talk about their individual approaches to writing, and suggest that Wagner is the more ambitious, and darker, writer at least on the evidence of this volume, and touch on the evolution that is demonstrated in this mostly stationary book.

0:43:10-1:06:42: Are Wagner and Grant writing Dredd differently because they see their own longterm prospects as writers differently? We start going into more details about individual stories — “The Sage,” which has amazing Glenn Fabry artwork, as well as “Bat-Mugger” — before distracting ourselves again, as is our wont, with bigger picture stuff, like whether or not there are intentional echoes of earlier material as evolution or simply retreads of greatest hits? Jeff also has a good point about the realistic pace of Dredd’s evolution as a character.

1:06:43-1:18:37: I really like “Bloodline” as a story in this volume, but Jeff’s not convinced, which leads to a discussion about the strip’s attitude towards cloning, Jeff’s attitude towards cloning as a narrative element, Dredd’s complicity in his own commodification, and Dredd’s attitude towards Mega-City One as a whole, and whether or not it’s actually genetic. (It’s a far better story than Jeff’s thinks, I promise.)

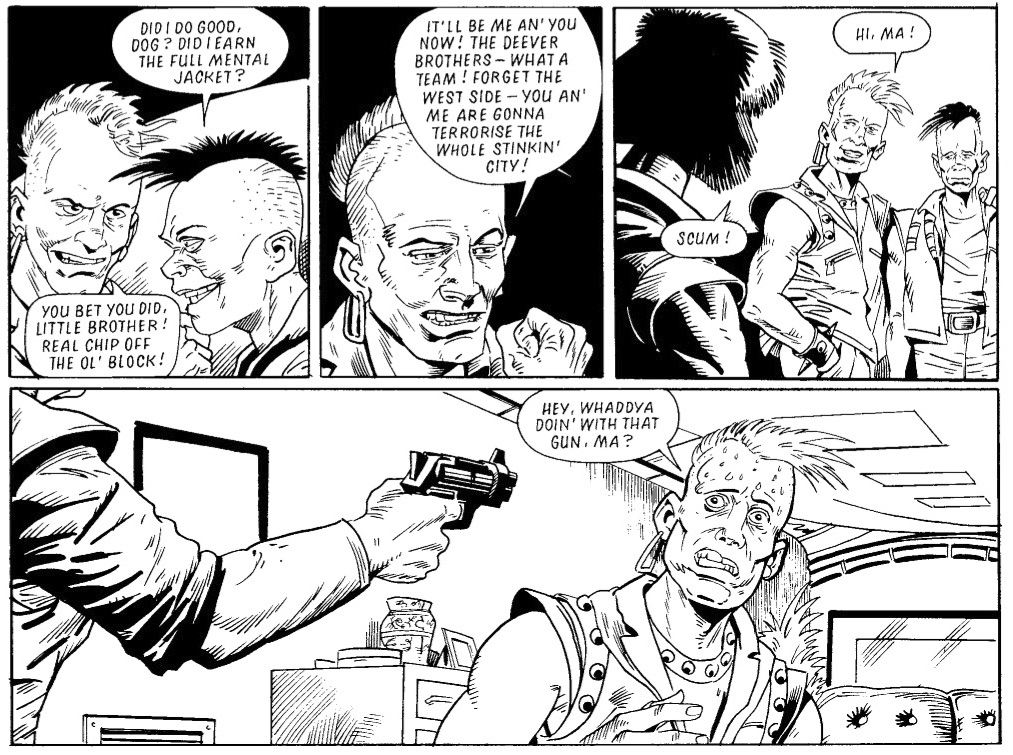

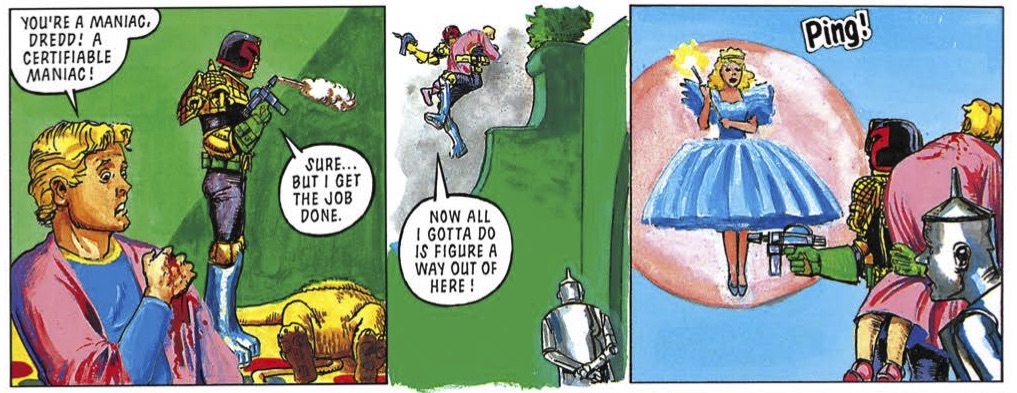

1:18:38-1:38:41: What are our top 3 stories in the volume? We each list our choices — “Hitman,” “Bloodline” and either “Full Mental Jacket” or “Twister” for me, while Jeff goes for “Hitman,” the “Night at the Circus” and “Night at the Opera” twofer, and “Crazy Barry, Little Mo” — before talking about “Hitman” some more, especially how much we both love to see Dredd in hospital and how great Jim Baikie’s art is, and then asking whether or not “Crazy Barry, Little Mo” is intended as a sign of just how bad things are in Mega-City One and whether they’re about to get worse. Also discussed: Just how much we dislike the “Coming Soon” teases that have snuck into the strip during this era.

1:38:42-1:53:21: Where does this volume fall in the grand scheme of Dredd to date? Jeff’s not too impressed, and if I’m more kind, it might be because I know what’s lying in wait in the upcoming volumes. We pivot from there to talk about the art in these stories and the European influence on show (to various degrees of obviousness, depending on the individual artists; I see you, Liam Sharp), as well as what Jeff is expecting — or, at least, hoping for — from future volumes, which includes at least one kind of spoiler of what’s to come in the very short term (like, two episodes from now).

1:53:22-end: Before we get there, though, we have to wrap things up with the traditional mentions of our Tumblr, Twitter, Instagram and Patreon, and tell you all that we’ll be back in a month for Complete Case Files Vol. 13. Until then, as always, thank you for reading and listening along.

Scattered thoughts:-

-Hold it a second. Do you mean to say that Jeff Lester has known about the Dead Man all this time?

Do you have any idea how much the suspense has been killing us (and by us I mean me) as to whether Graeme McMillan was going to try some device to trick him into reading it? Just how much willpower it took not to ask if you would be covering it?

-I wanted to pick up on something that Graeme McMillan said about Full Mental Jacket being the first time that we’ve had it said that it’s Mega-City One that drives people to do these things. I think that’s true in one sense, but not in another.

Going back a few years, essentially that was the justification for the judges — that Mega-City One was so dense and enormous that not even the tiniest infraction could be tolerated, for fear of what would happen. What I think is new is the subjective portrayal of that from the perspective of an actual citizen. Obviously, what that does is put the earlier years of the strip in a new light: what was the excuse to allow the young reader to enjoy seeing Dredd be Dredd is now presented to the somewhat older reader as something nightmarish and horrible.

-It’s worth observing, I think, that the giant shift from a comic in which Wagner (and Mills, Grant) were basically writing for children to one in which they are writing for people who can at least conceive of themselves as adults is more-or-less complete. It’s hard to imagine a less likely theme for the early years of the strip than aging.

By the same token, I think a lot of the “tune in at some point for more of this story!” stuff probably derives from an awareness that the strip is being written for readers who were in it for the long haul. It’s a comic fumbling its way towards figuring out what it’s supposed to do now that it’s no longer supposed to be a throwaway piece of cheap rubbish for readers who would cycle out as they became older.

Personally, I feel the loss of the anarchic energy that came from being ephemeral in 2000 AD’s first decade. Unlike David Morris, who mentioned that this is around where he stopped reading, I was still an avid reader, more so than ever, at this point. But that’s because I was at the perfect late-teens age to feel reassured by the higher physical quality and, especially, that sense that the strip was ever so slightly more self-important than it used to be. Reading this now, though, that self-importance has a slight but noticeable deadening effect – it’s not necessary to the serious stories, and it makes the silly ones seem out-of-place.

Allied to this is the big shift from the early Wagner period, in which his immensely fertile imagination kept coming up with new stuff and he would *eventually* bring some element back when he had a good idea for something to do with it. Now we have material being created with the explicit, textually announced, intention of bringing it back. (Which, OK, goes back to Stan Lee and the first PJ Maybe story, but is a lot more pervasively in-your-face in this volume than it’s been before.)

-I have to say, I wasn’t as wowed by The Hitman as our hosts. It’s obviously noteworthy for introducing the element of Dredd’s aging as an ongoing theme, and all that is well done. But the rest strikes me as pretty much routine Dredd — good in the way that Dredd is routinely good, but nothing special. And hasn’t Wagner done stories based on a similar concept at least twice before, in Citizen Snork and The Hunters’ Club?

Dredd working as a customs agent and as a wall guard makes me wonder how Dredd gets assigned to do things. He seems willing (and able) to do any sort of work that’s required of him and I wonder how he ends up doing it. Does Dredd do whatever he wants? Is there a central system that assigns judges to different types of tasks on a day-to-day basis? (And if so, does it apply to Dredd?) Do judges drive around semi-aimlessly and go to wherever there’s a crime report? Is Dredd always the one who volunteers whenever a call goes out on the radio? (Answer: Yes.) Does Dredd keep getting passed around between departments who don’t really want to deal with him?

Monday: “Dredd, you’ve been transferred to traffic duty in sector 8a.”

Dredd: “Check.”

*Dredd arrests a huge jaywalking group, busts up a carjacking ring, discovers the truth behind traffic light conspiracy group, and just generally causes masses of work for everyone in that sector.*

Tuesday: “Dredd, you’ve been transferred to, uh, fraud department. Report ASAP.”

Dredd hates paperwork and meetings, and as a senior judge he has at least some freedom on where to apply himself. And he abuses his position to avoid paperwork at any opportunity.

There have been times where he is transferred to do ‘mandatory’ work, so I assume nearly all judges get cycled between departments for at least some of the time.

All judges were to be assigned to a Manta Tank crew when they were first introduced (and bemoans he is not on the street cracking heads face to face),

he has to take the mandatory 24 hour period of off-time which he spends either arresting his neighbours, fidgeting in his spartan room and eventually into a sleep machine for several hours.

He is forced to attend block meetings in his home block, where he laments that he would be rather out shooting people!

But he is generally on the streets, for days at a time, cracking heads, following leads and just being Dredd. I think they mention somewhere that whenever it is announced that Dredd is assigned to a sector, crime drops by a significant margin, even before he arrives. But I also imagine he generates a lot of paperwork in his wake!

Has Dredd actually attended a block meeting as a citizen? That’s great.

It was asked in the comments last month what was being said in the letters page during Oz. As someone reading along with the Podcast using the Progs, I can tell you that mostly the letters pages were filled with readers drawings and silly jokes. While the comic was getting more adult the letters page was still definitely in the style of a children’s comic. But Prog 579 did contain an interesting letter, which links to some of the discussion in this podcast and the comments.

“Dear Tharg, I have read your zarjaz comic since Prog 2, even though I was very small at the time. but over the past two years, Judge Dredd has changed from a Justice-loving good guy to a fascist, bullying Bad guy. Back in the old days, people respected him, he was a man to be looked up to. He hated criminals and protected the people, but now he and the Justice Dept bully and cheat anyone who criticises them. A prime example of this is Prog 528 in the Dredd story “Reasons To Be Fearful”, where poor Guz Hardy became a victim of the Fear Amplification Beam, because he tried to expose the Judges’ dubious tactics. So, let’s stop all this and get back to the good old Dredd, maybe bring back some old enemies… Captain Skank for instance.

From Earthlet Gary Manley, Kenilworth, Warks. £5 winner.

Tharg replies: Nothing ever stays the same for ever. Not people. Not places. Perhaps Dredd has changed over the years. But so has Mega-City One. You should remember that Judge Dredd is older and grouchier these days, and upholding the Law on the streets of the beg Meg can only get harder for a man of his age.

Huh, neat! Thanks for providing that context!

As usual, our ever-thorough hosts commented on everything I would have wanted to say. I will not that the switch to full color also made it feel like I was reading a full-on Euro-comic. Not sure if it was the water colors or what, but it made the Dredd strips feel less like an American comic than at any point up until now. Like Jeff, I fell the coloring was a mixed bag It’s nice when the artists color their own work, but you can tell they’re not accustomed to it. In the same way when modern reprints re-color art in a way the pencil and inks weren’t laid out to hold.

What I will touch on is the split-up of the Wanger-Grant writing team. Out hosts mentioned it numerous times in previous episodes, but obviously this episode it became a focal point of the discussion. Was the break-up amicable or not, because it seems to me that Wagner is trolling Grant hard in a few of the strips. “The Hitman” seems like an outright repudiation of Grant’s side of the creative divide. A guy who cosplays as a judge but doesn’t grasp the judges… I don’t know. It felt kind of troll-y. Then you have the Bat Mugger story—with the A in bat stylized to resemble Batman’s signature cowl. Our hosts said this was an allusion to Davis’ Batman work, but Grant was writing Detective Comics at the time. The whole story was lampooning Batman, and I assumed that was specifically because Grant was writing it. Then Wagner does it again in the Crazy Barry, Little Mo, revealing that Barry witnessed his parents’ murder, leading him down the road to becoming an unstable vigilante. Another dig at Batman, which Grant was writing? Finally, the second part of Full Mental Jacket’s credit box has some weird spacing after Wagner’s name, right where Grant’s name would normally be. Was this removed after the fact?

I’m just wondering how acrimonious their falling out was. Maybe not too serious considering they both end up working on the Batman/Judge Dredd crossovers just a couple of years out from this.