Previously on Drokk!: With co-creator John Wagner now seemingly fully installed as the primary — indeed, seemingly the sole, Dredd writer once again, the strip seems to be once again finding its feet even as it appears to be quietly trying to reinvent itself…

0:00:00-0:02:51: After one of my favorite cold opens in Drokk! history, we introduce the volume we’re reading this time around — Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 29, covering material from 1998 and 1999, by Wagner, a small army of artists, and the surprise return of Alan Grant, who writes two stories herein — before getting down to business. Jeff also makes a great choice in naming the block this time around, too.

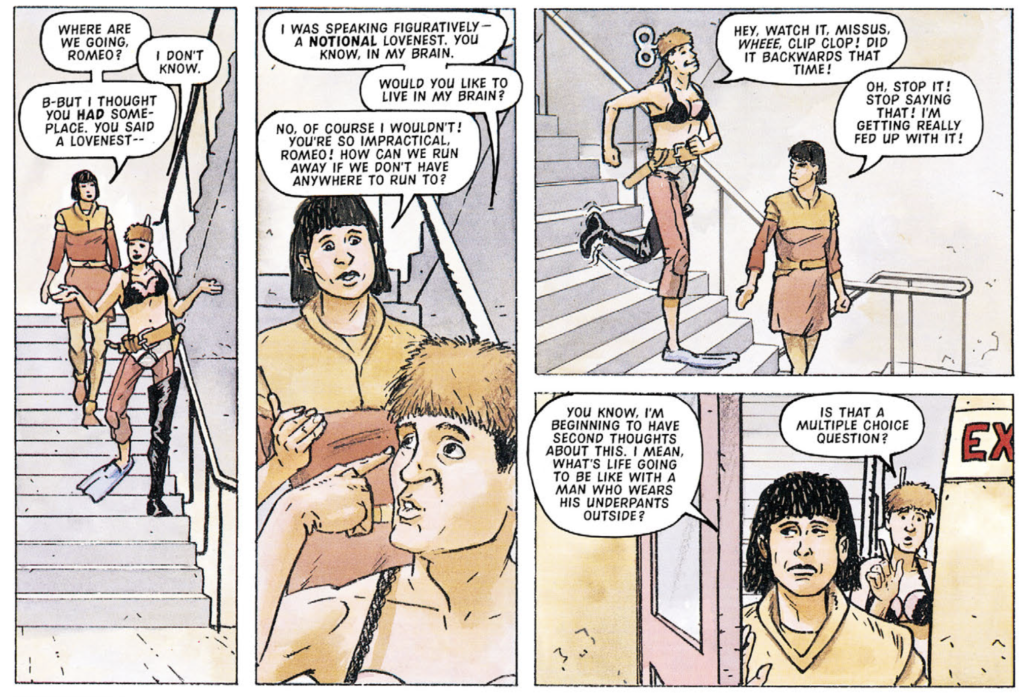

0:02:52-0:14:54: Jeff feels as if a way in to talking about this volume is to compare the returning Alan Grant to John Wagner, and so we talk about their differing approaches to Dredd, and the world of Judge Dredd the comic strip; according to Mr. Lester, Grant is “shaggy” in a way that Wagner isn’t, whereas I think that he’s just sillier — or, really, that Wagner plays his own silliness more straight. “He knows where he wants to hit his marks,” Jeff points out, but is that it? Is Wagner just a more assured, successful writer?

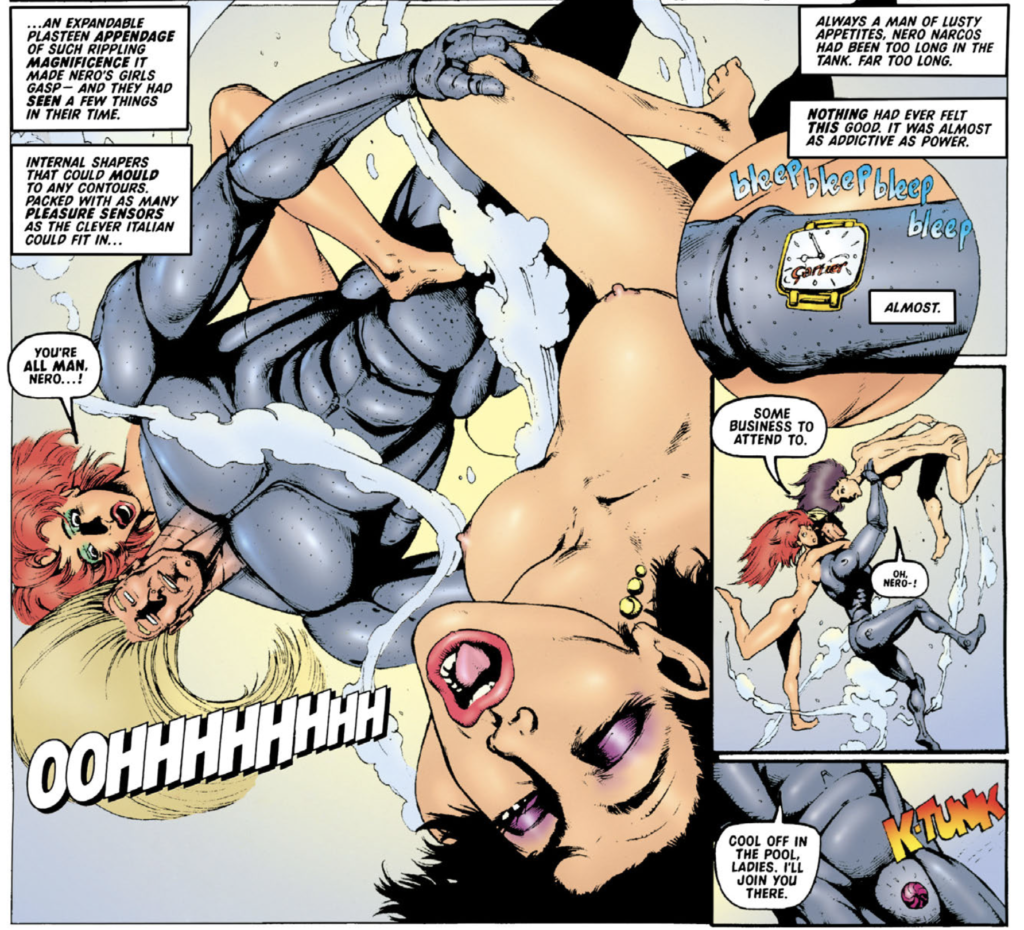

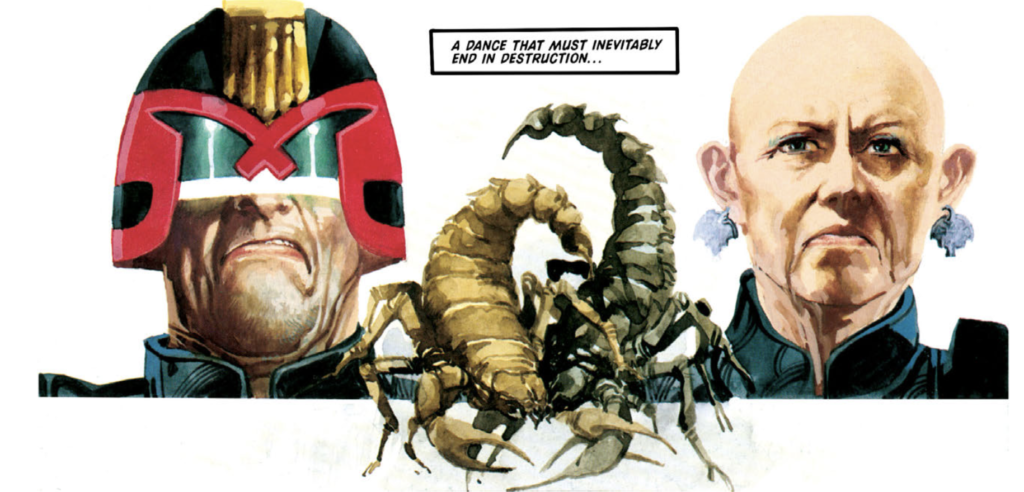

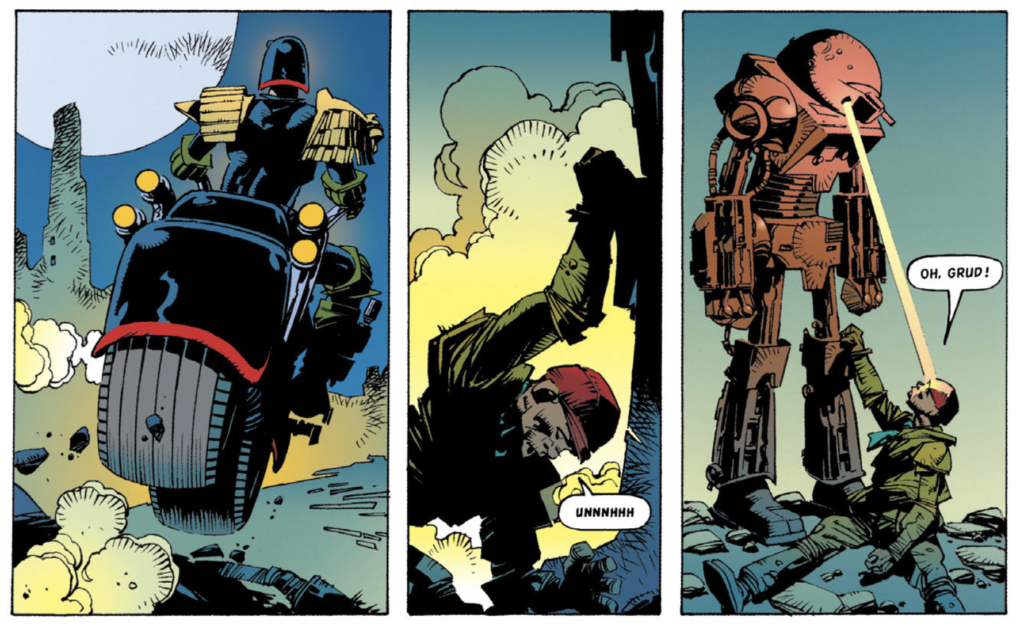

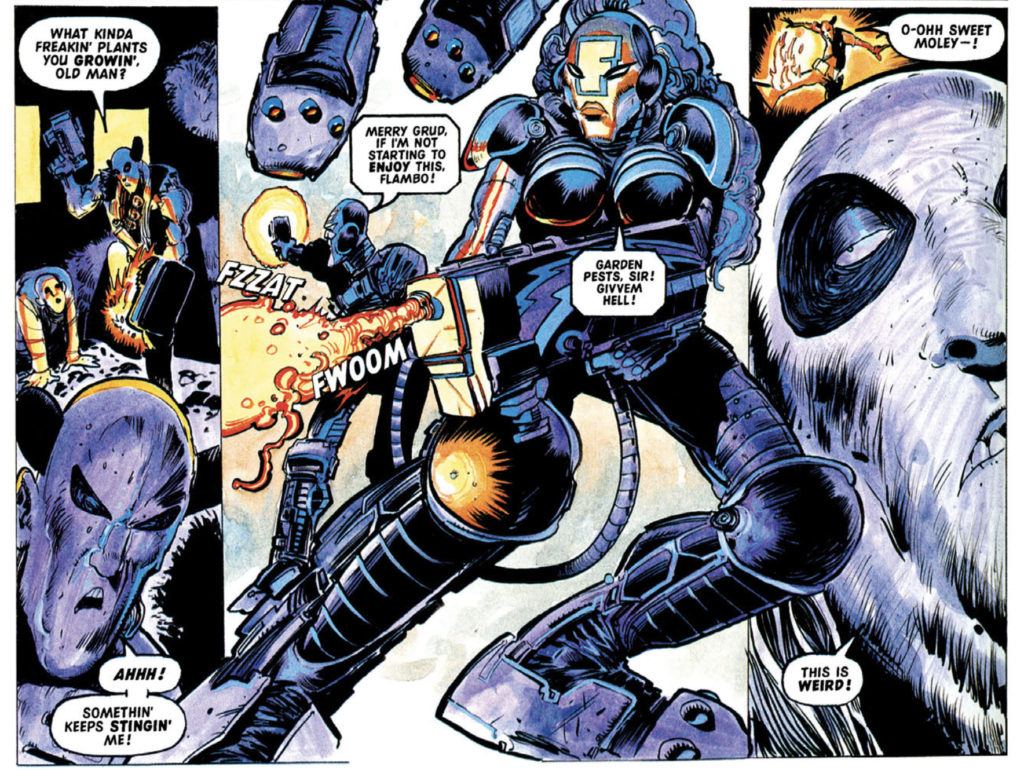

0:14:55-0:58:57: Because it’s us, we then go into the most frustrating portion of the entire book: “Worst of Frendz,” which is somehow even more disappointing than that title would suggest. Is it the “weird flex,” as I put it, of the threesome scene between two unnamed, unclothed women and the cyborg villain Nero Narcos, who has a checks notes telescopic penis? Is it the sub-Mark Millar dialogue? Is it the genuinely appalling artwork? Sure! All of the above and more. In theory, the story is a lead in to “The Scorpion Dance,” which is arguably the heart of this volume — one that I enjoyed and Jeff did not, and there’s a lot of back and forth about the reasons between the two opinions: I enjoyed the art, Jeff thought it was too crowded; I enjoyed the DeMarco arc, and Jeff thinks it’s a sign that neither Dredd nor John Wagner care about her as an individual; I like Judge Edgar as an antagonist, Jeff thinks she’s a sign that Wagner might be a misognynist, and so on. Jeff’s feeling that the storyline doesn’t go far enough is, arguably, somewhere that I think he’s on firmer ground, even if it’s a feeling I didn’t share because I’ve read further stories, but let’s just be happy that we can agree that “Worst of Frendz” is, by any stretch of the imagination, bad.

0:58:58-1:10:35: Fearful that we’re just spending an episode talking about what we don’t like, I ask Jeff about his favorite stories from the volume, and then share some of mine. We talk all-too-briefly about “Mega-City Way of Death,” which is genuinely great and should have been discussed more, as well as “Dreams of Glory” and a handful of other good stuff, before we somehow end up back on the topic of the slow burn of the Narcos plot and where it’s leading next volume. Look, apparently, we were in a circular frame of mind when we recorded this.

1:10:36-1:20:04: Jeff asks about two particular stories — “Wounded Heart” and “Christmas Angel,” both of which are sequels to earlier (more successful) Dredd stories — and I admit my disappointment in both, particularly the former, which I fully believe exists purely so Wagner can both meet his deadline requirements and use the pun that ends the strip. I also share my disappointment in “Simp City,” another strip that returns to old material trying to find something new to say, only to fail, and Jeff talks about how he initially believed better things were in the offing… only to quickly realize his mistake.

1:20:05-1:30:00: As we both agree that this volume, despite its shortcomings, is Drokk, not Dross, I suggest that the material from the Judge Dredd Magazine is stronger than its contemporary 2000 AD material, which Jeff takes issue with — we talk about that for a little while, before talking about favorite stories from the volume: Mine is “The Contract,” Jeff’s is “Mega-City Way of Death.” (Our least favorites are “Grud’s Big Day,” and “Worst of Frendz,” for the curious.)

1:30:01-end: As we close out the episode, I ask Jeff what he’s expecting from the next volume before teasing what’s actually coming up in the next volume. If that was my attempt at a surprise, though, he’s got me beat, by scheduling future recording sessions without me knowing, as you’ll hear me discover on air — and then we’re talking about Patreon and Twitter before skedaddling altogether. As always, thank you for reading and listening; we’ll be back in a month for a Dredd crossover with a difference.

And for those looking for the direct link… http://theworkingdraft.com/media/Drokk/DrokkEp32.mp3

Being parochial, ‘Simp City’ looked very Northern Ireland to me. From Norman Pride (layered, eh?) being an obvious Paisley caricature, the placards saying ‘No Simpery Here’ (geddit?), to the roadblock as a hilarious callback to the violent counter-marches Paisley led against the civil rights marches, it was a different read for me than yourselves. Add Paisley’s ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’ campaign of the 80s and it ties back to the metaphor very neatly.

Judge Edgar being Maggie Thatcher wouldn’t necessarily make her depiction not misogynistic. While disagreeing with practically everything Thatcher did, it’s clear that misogyny played a big part in her becoming such a figure of hate.

Another great volume of Dredd, which had me worried you might not have much to say. And while I had my issues with The Scorpion Dance, it also had the most meat to sink you teeth into. As I started it, I had high hopes, because some of my favorite Dredd has been the multi-part stories. Wagner was introducing so many disparate elements so quickly, I couldn’t help but wonder how everything would connect. Unfortunately, I’m still wondering. Vitus Dance would be a prime exhibit of what happens when a creator thinks a certain character is more interesting than the readers do. I think one of the issues with this story, and this volume in general, is that it was very much a transitional volume. Wanger is clearly breadcrumbing stuff with Narcos, which Graeme confirmed will pay off, but it’s simultaneous too overt and too subtle to be satisfying. Really reminds me of the early PJ Maybe stories. The Angel of Mercy feels the same way. Since we’re reading years of strips in the course of a few months, I think the lack of progress on those set-ups can be stifling, especially since we can read mutli-part stories and mega-progs all in one sitting.

The art was strong throughout, but Cam Kennedy’s stuff felt more cartoonish than I’m used to seeing from him. It wasn’t bad by any means, but it was lacking the realism of the Chopper stories.

I think your noted differences on how Grant and Wagner approach Dredd is spot on. I remember Graeme saying Grant’s Judge Anderson stories were not good, but never explained in what way. I’d be curious how they compare to what we see of him on Dredd solo. I do think Grant’s Dredd is a meaner Dredd than Wagner’s, and probably where writers like Millar see that and dial it up to 11. Wagner’s Dredd, for the most part, only kills when he has to. Grant and Millar have him kill because he can.

Another issue with Grant is his inconsistency. In the opening of Grud’s Bid Day, the M.C. says, “It was the Sovs who lost and the good old U.S. of A. who won!” which struck me as odd, because no one has ever referred to MC1 as the United States except when talking about the country in the past tense. Then in the second part of the story, Dredd says to the scientist/Grud: “You manica, America doesn’t exist anymore.” It’s weird that two different characters refer to MC1 as the U.S., and the Grant would bring patriotism into the mix. The judges are clearly fascist, but one interesting thing is their patriotism is always devotion to the law. We never see the nationalism you’d expect from a fascist society. Citizens are always admonished to do what’s best for the sake of the law, never to “Keep Mega-City One Great,” as it were. I’ll be curious what post-9/11 Dredd looks like when we get there in a few months (?) and if the judges are rebranded as full on good guys.

I’m curious about what influences Wagner had in this volume. You mentioned Starship Troopers for Banzai Brigade, but I also wonder if that movie about toy soldiers come to life calle Small Soldiers (1998) was also an influence. Wanger also gives a VR-based story, which was a hot topic in the ’90s. Interesting that he had the presence to create drone warfare instead of actual VR. And then the Four Marys had me thinking of the woman who tried to hire a hitman to kill the mom of her daughter’s rival for the high school cheer squad in the early ’90s. Wagner is clearly reading the newspaper and clipping articles for future stories.

Finally, two random thoughts. 1, this has to be the volume of the Case Files with the most nudity and swearing in it, no? And 2, I just realized Joe Dredd and the Justice Department have the same initials–J.D.

Can’t wait for next month!

Following up on Shadavid’s comment:-

Yes, this is where I think our hosts were wrong about Simp City being something we’ve seen before. Because we damn well haven’t seen simps used as a metaphor for Northern Ireland.

It probably reflects well on Graeme McMillan that he didn’t realize this, because I imagine that as a person from the Glasgow area he has at least some general familiarity with sectarianism as a phenomenon. John Wagner, of course, is from the same area…

But Simp City is more than just NI and parades in general — and while I absolutely would buy it as being to some extent about the ‘60s, as David Morris suggests, it has a more direct parallel in events contemporary with it. One that one cannot really doubt was intentional. This is another “ripped from the headlines” story which is about a specific thing that had been on the news a lot at the time: Drumcree. And it’s not subtle about doing a point-for-point transference. Gorblimey Road = Garvaghy Road. “Proximity talks.”

Background for people unfamiliar with news stories in the British media in the 1990s. Keeping it as short as I can. One thing about NI is that it’s hard to summarize anything, as one person’s “To be sure, it’s also true…” minor qualifier is another person’s major ”The central point here is…” fact on which everything turns.

Orange Order parades that march through Catholic areas during are a big point of conflict in Northern Ireland. It is an issue that resembles the removal of Confederate statues in the US, in that in one sense it’s purely symbolic, but the offensiveness is very real and very much felt by Catholics* — the marches are a display of the dominance of the majority Protestant community over the marginalized Catholic minority that is quite close to the way in which Confederate statues were typically set up c.1900-1920 as a celebration of the triumph of the white majority over the black minority.**

In the mid-90s, leading up to around the time when this comic was written, there were repeated clashes over marches in Drumcree on a yearly basis, in which protests by Catholics living on the Garvaghy Road to try to get the Orange Order to change the parade route were met by refusal on the Orange Order side. There is a particularly complicated back-and-forth involving the government and the security forces which is really hard to summarize: very loosely, the question was whether the parade would be banned (it was at one point, but it didn’t stick), and if not, what force would be deployed against Catholics to allow it to pass in peace.

Unsurprisingly, this was all accompanied by violence — there were riots, including in nationalist areas elsewhere in the province, murders of Catholics by loyalists, the worryingly familiar phenomenon of the RUC being rather visibly more keen on using force against Catholics than Protestants. This was all happening at a very tense time, as this was after 1994, when the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries were in an uneasy and fragile state of ceasefire.

In 1998, the Parades Commission (newly created body) banned the parade. Loyalists responded with frankly horrific violence. The worst incident was when the UVF petrol-bombed a Catholic house and killed three children. This had a big negative impact on sympathy for the Orange Order’s position, and essentially helped the ban stick rather than vice versa.

Around the time when this comic would have been written the Orange Order was trying to recover some of the ground that the loyalists had lost for it engaging in proximity talks with the Garvaghy Road residents, which is the significance of that detail. (“Proximity talks” are talks conducted through go-betweens — the Orange Order refused for very Northern Ireland reasons to have direct contact.)

OK, overlong history lesson over. Breathes sigh of relief. I hope it is evident just how directly this story is drawn from the evening news.

This is critical to one aspect of it on which our hosts commented and found puzzling, the both-sides-ism. This is not about Pride marches — it’s a very routine British (in the sense of the island of Britain) stance on Northern Ireland. In fact, it is probably *the* standard British attitude to Northern Ireland, when British people think about it at all, which is that there are these two tribes there that hate each other, and that’s what the conflict is about, and they’re both weird and awful.

As you can probably tell, that aspect of the story rubbed me up the wrong way, because that kind of British both-sides-ism about Northern Ireland isn’t about trying to have a balanced perspective, although I can believe that some British people might think that it is. It’s about saying, ”This has nothing to do with us. It’s all those people over there.” It’s about avoiding the fact that this all very much has to with Britain, that the Northern Irish conflict is critically shaped by a history of decisions that the British government has made. Sometimes good decisions, sometimes bad ones, sometimes enlightened, sometimes biased, sometimes short-sighted — but always *there*, never something that allows one to talk about Northern Ireland as if Britain is somehow “outside” the question.

An awful lot of it is a persistent British desire to support “our boys,” a dangerous impulse to preserve a childlike view of the British soldier as someone who can do no wrong. Comics are part of that — the historic dominance of boys’ war comics set in the Second World War is one of many inputs that shapes a view of the British army as an institution that can be admirable and competent, or comic and hapless, but never capable of evil. Probably the single most recurrent mistake made by the British government has been to cover up and lie about (only to have to apologise for, years later) things that soldiers have done — in order to preserve an idealized fiction that men with deadly force at their disposal are always going to do the right thing, as long as they’re British.

That’s the role in which Dredd has been cast in this story: the sane and exasperated outsider who has nothing to do with this but somehow has to deal with it through no fault of his own. The allegorical equivalent of the British government from the “Nothing to do with us” point of view. The story offers the British observer of the Drumcree conflict a fantasy in which the British security forces “just go in and beat the crap out of all of them, that’d sort it out.” The fantasy turns, of course, precisely on the idea that the British government and the British security forces are impartial outsiders who are not involved in any with all this — it’s just somehow happened to them for some mysterious reason.

It’s a shame, because there is something rather good about casting the simps as the Orange Order, of all people, making fun of the marches as silly dressing-up that no-one should take seriously. And casting Orangemen as what has up till now been a metaphor for gay people is also potentially quite amusing, for obvious reasons.

As it is, though, the fact that it’s the hard-faced “Gorblimey Road” residents who are coded as the Unionists (they first say “No simpery”) whereas the simps (who then take it up as “No normery”) are coded as the opponents to “normal” authority. That just feels like more of “Both sides are the same, and — and this is the important point — not like us..” Yes, this one was a misfire, for me.

*I am not saying that the position of Catholics under Stormont was historically exactly the same as that of African-Americans under Jim Crow. The level of brutality and terror inflicted upon African-Americans was greater, for one thing. But there are similarities — there is a reason why the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland modelled itself upon the US civil rights movement.

** It is more complicated than that — I am not the best person to articulate the Unionist and loyalist point of view on this, but the sort of thing that they tend rhetorically to emphasize is that they are legally exercising democratic and British freedoms to assemble and march “on the queen’s highway,” whereas civil disobedience (protests, such as sit-ins on roads to block parades) is illegal and the British state should not in any way give countenance to illegality in a conflict with legal acts. Orangeism is also a central and deeply felt component of many Protestants’ sense of identity, and the marches in Drumcree in particular matter because it’s near where the Orange Order was founded. And obviously, you always have in the background the poisonous fact that Protestants are (still, just about) the majority in Northern Ireland but the minority in the island of Ireland as a whole — the viewpoint is as much one of a vulnerable minority afraid of giving any ground as that of a triumphant majority.

Thanks to Voord for his wonderful contextual piece and to Miguel for the joy of ‘Wanger’. A mis-spelling that was perfect for this casefile.

Voord 99: Thanks for that great comment! I definitely saw the Northern Ireland parallels in that story, but didn’t know this amount of detail about the history.

I should thank Matthew Murray and Shadavid for their kind words.

I sort of feel that I should balance what I said about my irritation when people from the island of Britain take the ”Nothing to do with us.” attitude to Northern Ireland, by mentioning that this is also something that shows that, no, the British aren’t the villains of Irish nationalist conspiracy theory, either and the reason why British troops were in Northern Ireland was not selfish. For that matter, the British taxpayer’s tolerance of the rather large sum of money that Westminster continues to spend on Northern Ireland (more per capita anywhere else in the UK) remains very generous, all told.