Previously on Drokk!: Mega-City One as we know it — or, at least, as we’ve gotten to know it over the previous five episodes — is no more, as the result of the Apocalypse War, a storyline that both redefined the world Dredd lives in and the strip that’s named after him. But what can you do after that kind of monolithic event?

0:00:00-0:09:05: We quickly get into things, introducing that we’re talking about Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 6 and diving into the fact that neither of us really knew quite what to expect in the fallout of the last volume — a feeling only amplified by the fact that the first storyline features a wrestling robot called Precious Leglock.

0:09:06-0:19:11: Jeff has a theory about this volume, and it’s that John Wagner and Alan Grant are using the stories in this volume to set out their theory of the Judges and where they stand on the fascism of it all, prompted not only by this volume, but also what’s happening in the world at this moment. I also have a theory about what Wagner and Grant are doing as it relates to the Judges and judicial overreach in the wake of the Apocalypse War… but then, there’s all this weird humor getting in the way of the darkness…!

0:19:12-0:40:48: We dig into the unevenness of this book — never in terms of quality, but in terms of story and tone, certainly, with the combination of darkness and comedy being something we talk about. We also talk about cultural insensitivity in Wagner and Grant’s writing, and also the way the line of what’s acceptable culturally has shifted in the 30+ years since these stories were first published, and also the debt Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers may owe Judge Dredd, in terms of the use of satirical propaganda as storytelling tool. All this, and a tiny little note about a sneaky change in the world building of the strip, as the Cursed Earth sneaks inside the walls of Mega-City One.

0:40:49-0:53:01: In a volume where almost everything else is in constant flux, Wagner and Grant remain the constant, writing every strip. As they push against expectations for what Judge Dredd is as a character and a strip — in the process, pretty much demolishing those expectations by showing off how versatile the latter can be — Jeff and I talk about the way in which the writers are setting out their command and control of the series. And, getting back to Jeff’s theory, is this the volume where the two decide that the ultimate purpose of Dredd is simply to entertain?

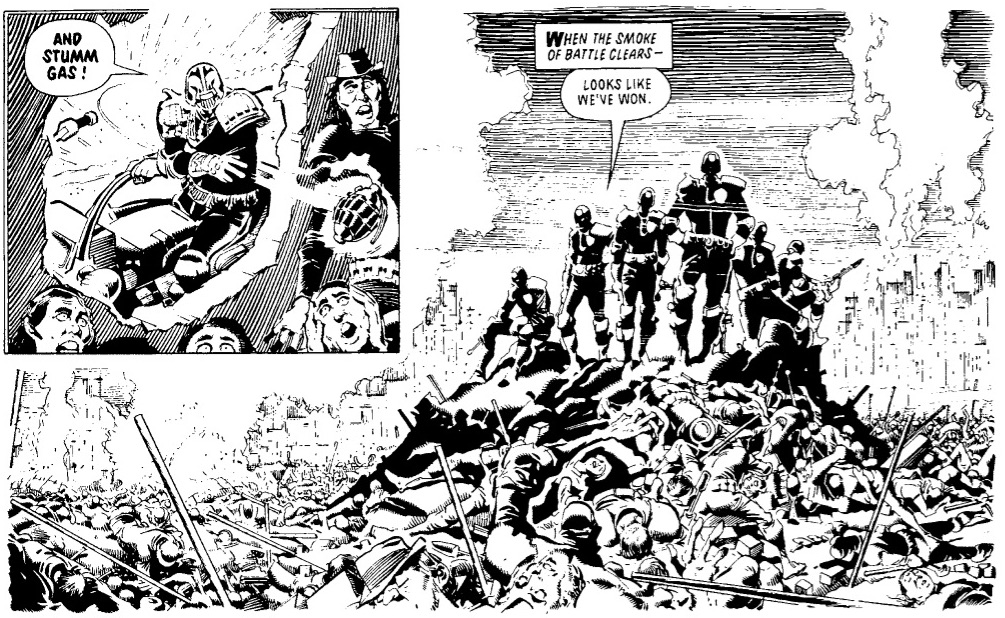

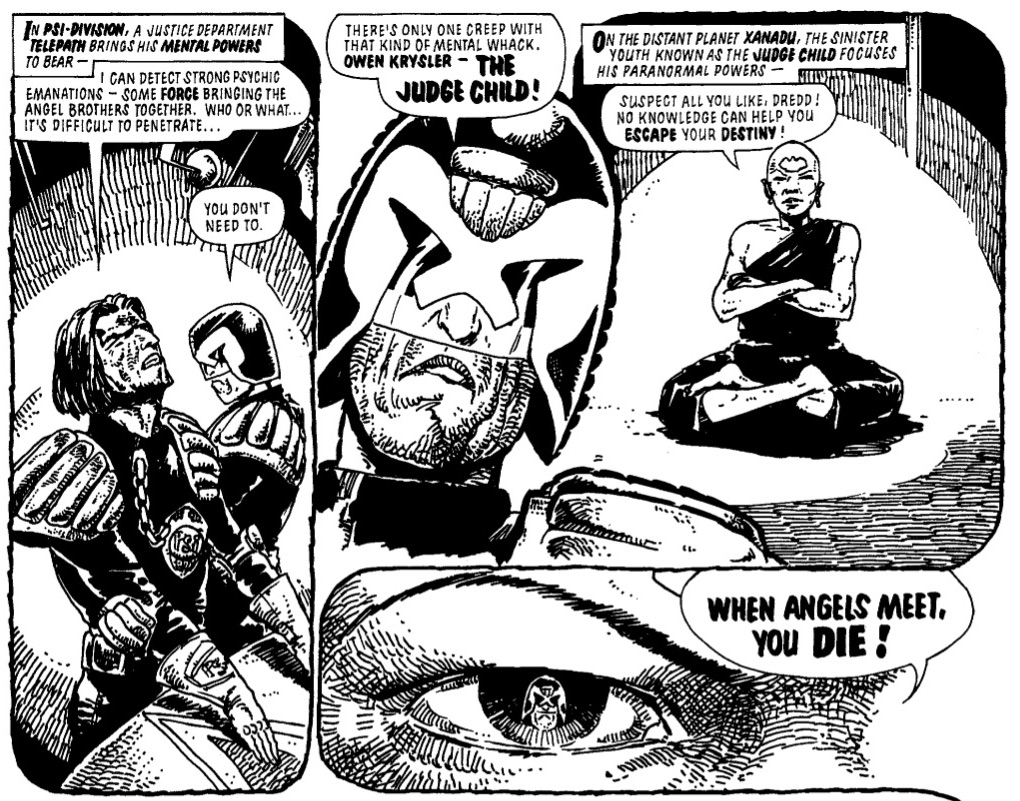

0:53:02-1:18:06: We turn, eventually, to our favorite stories from the volume, beginning with mine: “Destiny’s Angels,” in which Wagner, Grant and Carlos Ezquerra take what would in someone else’s hands be a very dramatic epic and push it in an ever-more silly direction, leading to us talking about the multi-layered approach of the writing in Dredd. There’s also an impressively over-the-top conclusion to the story, which prompts Jeff to use the phrase “This remarkable achievement in the world’s grimmest whimsy,” which feels very appropriate, considering.

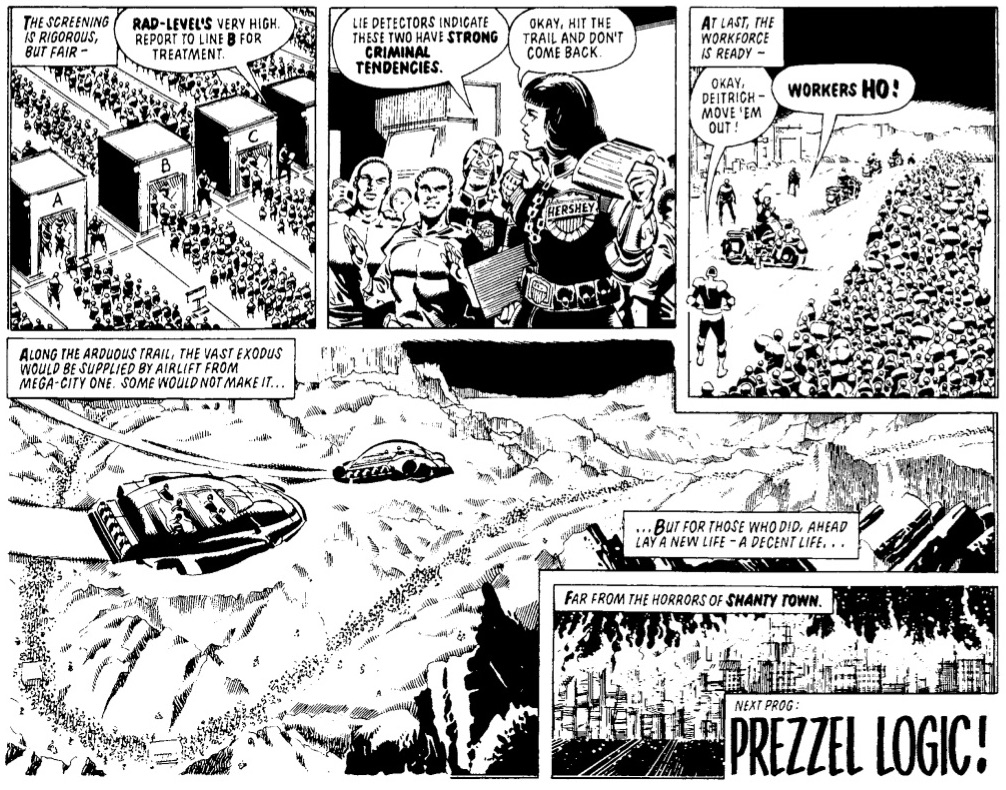

1:18:07-1:58:44: Then, to Jeff’s favorite story in the volume, “Shantytown,” which has a particular hold over him, as he explains. It brings a lot of subjects with it, not least of which the inherent fascism of the Judge system and Judge Dredd as a comic strip, and how complicit both the readers and the creators are in supporting that. Amongst the many things under discussion: Is “Shantytown” an occupation story in which we’re expected to root for the occupation force merely because it’s their name on the series’ title? Are the Judges evil? Are Wagner and Grant co-signing onto a cruel, dehumanizing system? What constitutes a happy ending, and what undercuts one? Is Dredd inherently trustworthy, despite everything? Is anyone else surprised by Jeff dropping a Mitchell & Webb reference? Okay, that one’s not actually discussed, but still.

1:58:45-2:19:59: We move onto other things that are particularly grim about this volume, including the unofficial imposition of martial law and constant growth of the Judges’ power in this volume. Does this represent the most honest depiction of political power in comics, and if so, is that accidental, considering that 2000 AD was still very much a kids’ comic at the time these episodes were printed? Also, we talk about Jeff’s fear that Wagner and Grant may have fascist tendencies based on comics’ history of important creators drifting in that direction, and once again touch on the idea that the tension in Wagner’s writing in particular when it comes to the idea that the Judges serve a purpose in their community is an important one to Judge Dredd as an overall strip.

2:20:00-end: We wrap things up with mention of the fact that, for those showing up at San Diego Comic-Con this week, I’m going to be on the Judge Dredd: Satire or Super-Cop panel on Thursday afternoon, before going into the usual mention of Tumblr, Instagram and Twitter, not to mention our Patreon. Next month, we’ll be back with Vol. 7, in which there are werewolves, competitive eating contests and, most importantly, the arrival on the strip of Cam Kennedy. As always, thanks for listening.

And for those looking for the direct link, it’s here: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp6.mp3

I’m glad our hosts did touch on The Executioner at the end. I kept waiting for it to come up and going, “Come on, it deserves a mention at least!” One thing I love about Judge Dredd is the way that it can take what should be bland, boring stories and make them interesting. The Executioner, if you summarize it, is an extremely clichéd vigilante-justice story. It’s very much the sort of thing that you would find taking up an hour of television on any given episodic cop show of 70s and 80s, the kind with a different villain every week. Right down to “But she’s a woman!” It would not surprise me if it was directly lifted from some episode of Starsky and Hutch or whatever.

But somehow it’s one of the best stories in the volume. Well, there’s Ezquerra’s art, obviously. There’s also the familiar 2000 AD cynical humor: the TV personality announcing the poll, the idiotic copycat killer (and I love that you can’t tell if the other judge is deliberately winding Dredd up or not), Judge “Portnoy” in a story about motherhood (a reference which I certainly wasn’t old enough to get at the time).

But I think it’s more than that. It comes down to what our hosts said: after this volume, Dredd can’t surprise (not easily – “Letter from a Democrat” did at the time give me a sense of “Whoa, this strip is changing”), because it’s shown that it can do so much. The Executioner doesn’t stand by itself. It’s a standard story done straight in a series of stories that are much more weird. And that makes it stand out as *not* the same. It’s not dull and boring: it’s another reminder that Mega-City One is big enough and varied enough to accommodate just about any tone and theme.

The Executioner is also the first time the strip has revisited what it did in Un-American Graffiti. Blanche Tatum is the successor to Marlon Shakespeare: the first character since then to be the protagonist of the story who defeats Dredd.

(As always, excluding Walter, where his victories over Dredd are purely comic, a suspension of the normal rules. Although humor is relevant: One minor touch that reinforces Dredd’s overall failure is when Dredd is the butt of the joke in a way that he usually isn’t, when he leans on the poor victim’s leg and has to apologize.)

Both Blanche and Marlon are figures who create new identities for themselves — in a sense, they create new characters to replace Dredd as the main character of the story. There’s something there that I can’t quite put my finger on about how Dredd’s own identity is completely subsumed in his image as a judge, an icon — something about how when Blanche puts on that hood and becomes the Executioner she makes herself the equal of the man who never takes off his helmet.

Unlike Marlon/Chopper, though, Blanche/the Executioner isn’t a straightforward hero. The story efficiently communicates how awful it is that Blanche is driven by her children’s anger (that amazing Ezquerra panel of her daughter’s face) to abandon those children — the Executioner inflict on them the death of their mother on top of the death of their father. But still, like Marlon, Blanche wins: “She got her wish.”

I can’t figure out why Judge de Gaulle is called that, though.

Our hosts’ discussion of Shanty Town was one of the highlights, not only of this episode, but of Drokk! so far.

Especially the observation about how this is about taking a classic Western plot and exaggerating it. I think that makes Graeme McMillan’s case about the ending not being a happy one. You’re set up to expect that the “good people” will be looked after in a reformed, orderly Shanty Town, very possibly renamed Dreddville. And then Wagner & Grant change the script and yank in slum clearance as the implied analogy.

(One minor note in favor of Jeff Lester’s reading of the judges as the bad guys. One of them is called Blofeld, of all things.)

I’ll be really interested to hear what David Morris made of this. I’m from the South (of Ireland), not the North, but I can’t say that I was quite as hostile to the notion of the state using force to prevent paramilitaries using violence to dominate local communities as Jeff Lester and Graeme McMillan are. OK, I’m loading things a little by saying “paramilitaries,” but I do think there is more of a case for saying that it is not per se wrong for the state to seek to have a monopoly on violence and maintain the rule of law in the interests of, you know, people not being murdered and kneecapped.

This is not necessarily a right-wing point of view, either – it’s essentially the same argument as the left-liberal argument against right-libertarians that no, your minimal state in which we all have privatized security in place of police forces is in practice going to look like places with weak states have historically looked, which is violent and unpleasant, and dominated by local powerholders. It’s the classic distinction between a weak state and a state whose powers are limited to preserve people’s rights, but can act vigorously within those limits to restrain powerful private actors.

But, OK, Mega-City One is no-one’s idea of either a weak state or one with limited powers. It’s the strong authoritarian state in which there aren’t any limits.

There’s a long tradition (it goes back to the Greeks and Romans) of worrying about robber bands in the context of the state. What’s the difference between the state and a robber band? It teases out questions of what is supposed to make the state legitimate. “Without justice, what are states but big robber bands?”

I think that’s a useful lens through which to view this story. Jeff Lester seemed to me to be framing this as a story in which the judges invaded and overthrew a political entity that had its own legitimacy. I have to say, my heart doesn’t bleed for Girth and Mad Mox’s claims to be any sort of legitimate government whose claims to sovereignty deserve to be respected. I think it’s the other way round: the story raises the question of what the difference is between Shanty Town and Mega-City One. Is there any? Are Dredd, Hershey, and McGruder any different from Mad Mox in any way except that they’re better at it? Is Mega-City One just a really big criminal gang, for all that it defines its ruling elite as the polar opposite of criminals?

I’m not sure that Wagner & Grant have a clear answer to that question. I think there’s a part of Wagner that’s pulled towards a pessimistic Hobbes view that there needs to be someone to keep order, and that need gets bigger the larger urban communities get, because the alternative would be chaos. That recurrent theme in pre-Grant Wagner Dredd that Mega-City One has to have an absolute unbending zero-tolerance policy for the most minor infractions, because otherwise everything would just go to hell. And that the only thing that can restrain this necessary disciplinarian is some sort of self-discipline imparted by years of training (because by definition, the sovereign can’t be subject to anything else aside from itself).

But on the other hand (and this becomes more noticeable when Grant joins Wagner), there’s the idea that the price that you pay for that is that the disciplinarian is horrible and inhumane – inhuman, really. They will do anything, sacrifice anyone, to maintain order. The robots like Precious Leghorn are more human than Dredd or McGruder. Don’t you really admire the Choppers – even the Blanche Tatums – more than you do Judge Dredd? Don’t you kind of wish those guys getting together to plan the perfect crime could get away with it, just once?

Then again, Dredd seems genuinely appalled and humane in the Condo story. I think Wagner & Grant aren’t sure how far down this road they want to go.

Well, I laughed aloud when I read this comment, as Voord 99 absolutely has my number. All the way through the Shantytown discussion I kept thinking about my younger brother who used to live in a part of Belfast where every so often you’d be told you were expected to turn out for a demonstration or some other bit of political theatre. You went, or you were driven out of your home. So, yes, it’s interesting times when the state loses the monopoly of violence.

He also asks if there’s any real difference between Dredd, Hersham, McGruder and Mad Mox. I immediately thought the difference is the judges motivation isn’t selfish. They aren’t trying to to gratify their selfish desires. I then found myself wondering why I considered that to be so important. One of those things that seems less clear the further I go.

There were two surprises for me with Shantytown. First, considering the judges on top of the appalling pile of corpses, I couldn’t see what was motivating the people to keep fighting. That pile of death speaks of a surprisingly high level of discipline and morale. Second, I expected more of Mega-City One to be like this after the Apocalypse War. The survivors have kept it together remarkably well. My stab at an in-continuity explanation would be the whole world was transformed to a bunch of trauma cultures by the first big nuclear exchange, so it doesn’t look much different now.

The discussion of Dredd and fascism got me wondering if Ezquerra ever said anything on this. Given that he lived under fascism it’d be interesting.

The perfect crime group seemed to meet in a part of MC1 completely untouched by the Apocalypse War. I was pretty disappointed with organised crime’s response to the post-war situation. All that chaos and a shortage of judges, people needing so many things and all those vulnerable people. So much opportunity and they’re playing games.

Graeme has instilled in me what is probably an unrealiseable ambition: to see Ron Smith draw Li’l Abner. He’d have been so good at it!

He also asks if there’s any real difference between Dredd, Hersham, McGruder and Mad Mox. I immediately thought the difference is the judges motivation isn’t selfish. They aren’t trying to to gratify their selfish desires.

You’re right — I think that’s a key point.

It reminds me of something that at least one person pointed out about Dredd in a letter-column at some point in the ‘80s. What this system is really like is not any historical actual existing state — it’s Plato’s Republic. You have Guardians in control of everything, who can be trusted to be disinterested and altruistic in their intentions, because they’ve been educated from childhood to be that way.

It comes back to how the central element in this fantasy is the Academy, the idea that if you just gave the right people the right education, and washed out everyone who turned out to be unsuitable, you would produce a superior class who would “naturally” deserve to be in charge. (Which definitely does have relevance to fascism, but also to things that were somewhat closer to home in postwar Britain, I think.)

Although I did notice that Wagner & Grant had noticeably less talk this volume about how amazing the Academy is and how having gone through it made Dredd what he is. That being said, when they do, it’s big: the five-year old cadets laying done their lives, the whole concept of Blanche Tatum as the almost-judge who (and this comes back to your observation) pursues a personally-interested version of Dredd’s obsessive enforcement of impersonal, disinterested justice.

On the whole, I do think that any discussion of Judge Dredd in this era is radically incomplete if it doesn’t talk about Margaret Thatcher. One curious thing about The Apocalypse War that didn’t come up last time is the accident that made McGruder Chief Judge as a stirring-speeches wartime leader at the same time as Thatcher’s image got a massive shot in the arm from the Falklands War (which took place while the Apocalypse War was coming out, although it was rather shorter).

Concretely, it boosted her popularity by 10 points and is often considered responsible for her election victory next year. Also, it changed the nature of that election victory — the manifesto on which the Conservatives won in 1979 was much less aggressively, well, Thatcherite than the manifesto on which they won in 1983. But its cultural effects are larger than that. To a very significant degree, the Falklands War is when Margaret Thatcher became *Margaret Thatcher,* when she ceased to be an ordinary politician and became the iconic/demonic pop-cultural figure that dominated so much of the imagination of ‘80s Britain. Loved by her own (that famously overwhelming bond with the ABC1s), loathed – absolutely loathed – by others. For the first group, the Falklands War made Thatcher a plausible successor to the mythologized Churchill, a myth in her own right.

(A phenomenon aided by the erasure of the Korean War from British collective memory: Clement Attlee, not Margaret Thatcher, is the most significant wartime prime minister since Churchill. But anyway.)

Som McGruder=Thatcher? McGruder was eventually to be made explicitly into a Thatcher expy by giving her the first names “Hilda Margaret.” That hasn’t happened yet, but it’s hard to see how, in its historical context, making a severe-looking woman the head of government could avoid being a reference to Margaret Thatcher. (For what it’s worth, JOPS = YOPS.)

This is one of the points on which the tension that bothered our hosts becomes especially interesting. I think it’s fair to say that, in this era, Wagner & Grant put in occasional sly ironic touches that subvert Dredd’s image as a hero, but 90% of the time, Dredd is a traditional idealized boy’s action hero, with all of the unquestioned moral authority that goes into that. It’s arbitrary to read the minor notes as the “real” meaning – one has to wrestle with the fact that this is a story that most of the time really does want you to root for the authoritarian.

That has to implicate McGruder/Thatcher, because she’s his boss: not the hero, but the M figure of authority who authorizes the hero to act. If she’s not admirable, Dredd is compromised unless he pushes back against her (and he never does).

So that dominant hero/suppressed bad guy tension has to map onto what the story is saying about Thatcherism. There are some definite negative touches. Especially the close-up on the skull earring – which, yes, is part of the character’s established character design, but which that panel takes brilliantly out of context in a manner that’s especially striking in a comic done in the action-packed, efficient British style, where you can’t easily take time to linger on something that’s purely for tone.

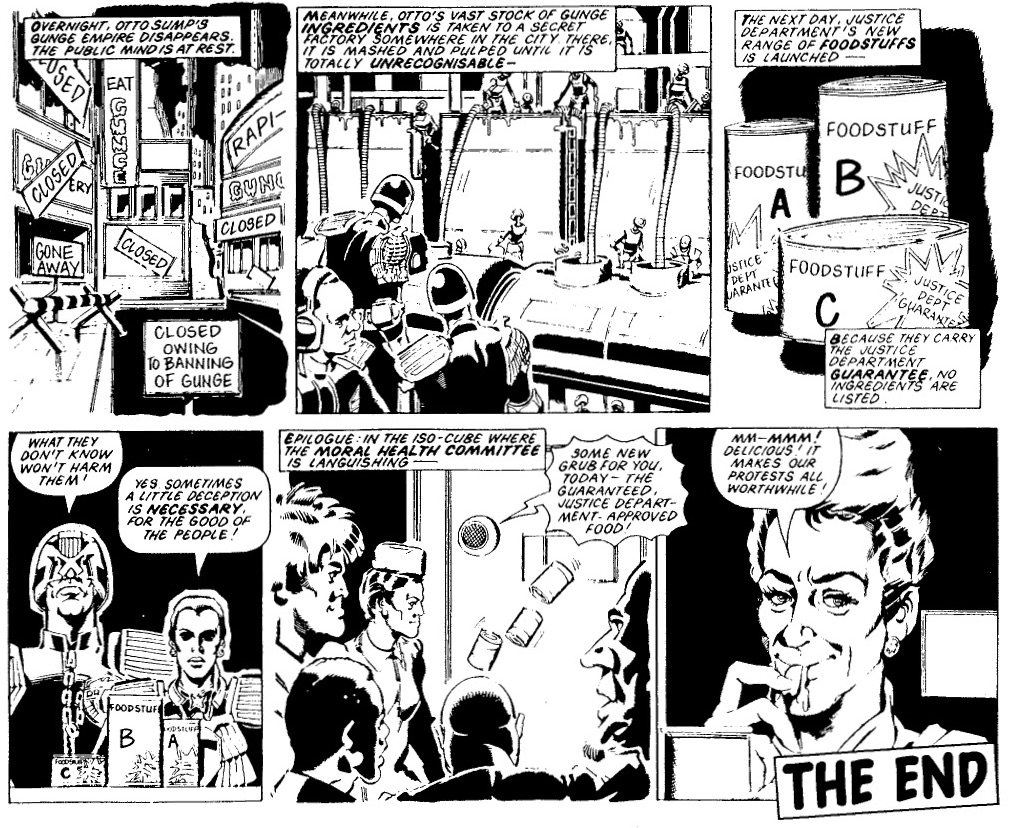

But they have a tendency to be justified or justifiable. What McGruder does to the fungus sufferers, for instance, is not great, but there’s a definite touch of “lying to them for the public good” about it. That has a very direct relevance to the way British government operated in the period. It had a very high degree of acceptance compared to most other liberal democracies of the desirability of keeping things secret from the public in the interests of the public good (e.g. D-notices). The Thatcher government was a forthright defender of those policies and methods (which were much more effective in the pre-Internet period than they are today). In other words, it is not at all obvious that McGruder is in context being criticized for her decision: it was the sort of thing that the actual British government was able to do and was expected to do. Not without controversy, of course, but I don’t know that one can start when reading a child’s adventure comic by saying “Assume a Guardian reader.”

So, inevitably, one looks for some individual with an overtly satirical anti-Thatcherite theme to undermine all that. I commented that I thought that Un-American Graffiti was the first clearly anti-Thatcherite piece. The interesting thing is, I think it’s also the last (for the moment, obviously). There’s nothing like it in this volume. One has to wonder if (very possibly subconsciously – I doubt either were Conservative voters) Wagner & Grant were trimming their sails in the post-Falklands era.

Oops. Forgot a point I meant to make. In particular, there’s a shift in how the strip regards joblessness.

Early on – under the Callaghan government and the first few months of the Thatcher government- unemployment is not the fault of the unemployed. They want jobs, desperately, but the jobs just aren’t there. I commented that this can be read as a prescient rebuke to Thatcherism’s presentation of the unemployed as fundamentally lazy. Un-American Graffiti is a brief moment when that isn’t prescient, but present, as unemployment skyrocketed and was increasingly blamed on the current Conservative government, not the last Labour one.

But now, in the post Apocalypse War/Falklands War era? Look at how McGruder’s recruitment of forced labor is presented: the citizens haven’t been used to working, but now they’ll learn how to. There’s no sense that the fact that the citizens didn’t work before *wasn’t their fault.*

This lends itself to allowing the citizens of Mega-City One to be read as a coddled group who have been indulged by the welfare state, but no more.

I’m curious how the economics of Mega-City 1 work, because superficially, that scene saying a mass of citizens are being conscripted into forced labor is just terrible. But in all the prior volumes, we’re told that 80% (more?) of the people don’t have jobs and all they want to do is work, so is this actually bad? If it’s such a welfare state, why are there classes? How do people who don’t work make money or purchase goods and services? If you don’t have to work and your basic needs are covered, is there only real reason there are crime syndicates is because they’re all jonesing for something to do? Again, this is one of the areas where I feel there’s a lack of macro world building to explain how this works, and it makes it difficult to come down on one side or another in arguments such as the aforementioned question of judges’ fascistity.

Also, if Mega-City 1 is about the size of 10-12 U.S. states, how does everyone seem to know who Dredd is? Is he really out patrolling the equivalent of 1/4 of the United States every day, and is a Lawmaster so fast as to get him home in time for supper no matt how far out he patrols?

“In America, a hundred years is a long time. In Europe, a hundred miles is a long way.”

The failure of Judge Dredd to reflect just how big Mega-City One would actually be is to some extent a European thing. The scale of the US is genuinely hard to grasp if you didn’t grow up with it. I still remember the first time I went to California and realized just how long it takes to get from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

But, yes. It was really obvious in the Apocalypse War, in which Dredd’s small band of rebels are sufficient to cut all the possible routes from north to south, and there appear to be about five or six of those routes at most.

Interesting you mention scale: I seem to recall from a Wagner interview at the time that part of the world building reason for the Apocalypse War was Mega City One becoming to cumbersome because of its size and reducing it by two thirds was necessary from a storytelling perspective.

By the way, much as I love Jeff and Graeme’s discussions, I equally enjoy the comments, especially from you Voord 99, as you seem around the same age as me and remember reading 2000ad at the time these were printed.

Which leads to the “tension” regarding the politics of the strip. In all honesty the first 800 issues of 2000ad* grew up with the readership: I was 9 when prog 1 was released, 24 with prog 800, and the writing reflected my maturity during that time, although it was never a continuous growth, but awkward spurts and occasional cul de sacs (I may have mixed up my metaphors there).

*I use prog 800 as a milestone as it’s the point where Wagner ceased being regular writer of Dredd, although still maintains an overview and contributing stories both to 2000ad and the Judge Dredd Megazine. It’s also, in my opinion, the start of a noticeable decline in quality during the 90’s that it’s never fully recovered from, in my opinion, reaching its nadir in the notorious prog 1066 in 1997 : http://progslog.blogspot.com/2010/02/prog-1066-281097.html

The discussion engendered by this volume made this episode one of the most satisfying eps of Drokk thus far.

Where Dredd falls on the fascism spectrum seems very much up to debate, or at least has to be taken on a story-by-story basis. I believe it was vol. 2 where Dredd comes back from Titan and he’s not yet been re-invested with the authority of a judge, so he just nonchalantly observes the citizens committing crimes. I believe at the time, our hosts, and the commenters, pointed this as being an example of Dredd not being fascist, because he believes in the system, he’s not personally interested in being a totalitarian. Usually fascists are seen as having a Greek-tragedy level flaw in the need to exert absolute power no matter what, because usually they’re big, insecure bullies. We do, however, see Dredd become way more authoritarian which each volume. I couldn’t believe in the first volume the level of, for lack of a better word, compassion he shows toward citizens suffering from future shock. He really goes out of his way to not kill them, which was striking to me. Contrast that with this volume where he just shoots a guy for antagonizing him from the opposite end of a one-way street.

One reason why I can’t get a read on the fascism level of the judges is because of the lack of macro worldbuilding. On the micro, you get a nice tidbit with almost every prog, but in the macro there’s a lot left to be desired. If the judges are invested with legislative, executive, judiciary, AND military powers, why is there a mayor? Is it a totalitarian democracy? Is the mayor’s office a titular position only? The judges do what they want, but they don’t do it out of self-serving greed, like many a dictator. Really, there’s evidence for and against them being fascists, and maybe that’s why Wagner and Grant can’t themselves decide, because it would require too much world building and not enough storytelling in the 8 or so pages they’re allotted every week.

Evidence for the Judges Being Fascists

-The clothing is very stormtrooper like, and I, like Jeff, couldn’t help but notice the SS mark the judges’ visors form.

-They propagate and enforce the law, and there’s no real trial system, as far as we’ve seen

-No one seems to air grievances with the judges or protest them

-Everyone is afraid of them.

-They have the complete run of the city and can inflict any indignity upon the citizens with impunity as long as it’s in the name of law.

Evidence that the Judges Aren’t Fascists

-Mention of a mayor. (Of course, this could be a akin to a situation as in countries such as Pakistan where there’s a civilian gov’t, but only on the military’s say so.)

-Judges are not assigned to each block. You think this would be a no-brainer in terms of keeping everyone in line, but that type of thing is left to each block’s (civilian) security department.

-Judges cannot do *whatever* they want, because as soon as they break the law, they’re out, as we’ve seen numerous times. Contrast this with a true fascist state where the “middle managers” of the state use their position for self emolument, and get away with it, as long as they protect the state from dissenters and its other enemies.

-No one ever protests the judges, but they do form groups and protests. Unlike most gov’ts, this usually spur the judges into action to at least investigate why the citizenry are so riled up.

-Finally, Judge Cal. If it weren’t for his story, I’d have an easier time viewing the judges as fascists, but Judge Cal was presented as an archetypical fascist, from his unhinged leadership to his development of a cult of personality around himself to his desire to crush any and all dissent to his micromanaging of the lives of the populace. He even makes a deal with bad-faith external actors (the aliens) to assist with keeping himself in power. Does Dredd, or any of the other judges that are not corrupt, every display anything like that?

And yet…my gut still tells me they’re fascist. But I’m also the type of guy who found the ending of Black Panther problematic, because the film asks us to cheer on a monarch/dictator returning to unchallenged rule.

Just to add another detail: actual historical Nazi Germany had as its cardinal principle the Führerprinzip, according to which the leader was explicitly meant to be above the law. Arbitrary exercise of power unrestrained by law was the point. Law was not elevated as the higher good to which all things should be referred: that was the nation.

Which is not at like Mega-City One, which is all about the idea that the law is absolutely rigid and no-one is above it, and more importantly, seeing the law as the highest ideal. The law is not presented as answerable to anything else.

In a sense, I think focusing too much on fascism could lead one to ignore things that are more sensitive and awkward than that, because they’re closer to home. Judge Dredd can be seen as what would happen if you took the traditional “law and order” tendency of the Conservative Party to an absurd extreme.

I think, though, that looking for hard-SF worldbuilding where things are consistent and make sense as a whole is not the best way to look at Dredd. This works better when viewed as a bizarre crazy fun-house world that’s just a little surreal, where any single thing can be turned up to 11 for the purposes of one story regardless of whether that’s easy to fit with some other thing in another story.

Judge Dredd has a lot in common with Doctor Who. Stories move between premises and genres freely, but in Mega-City One there’s no TARDIS to move between them: they’re side-by-side in the same impossible city. To put it another way, although Judge Dredd is a story that’s all about constraints on characters within the story, there aren’t a lot of constraints on the story itself — it can go pretty much anywhere, as long as Dredd himself stays consistent. The price you pay for that is that it doesn’t have a coherent and credible setting as such, except thematically.

I think Dredd looks more like a religious zealot than a fascist. The Law is his holy text and he will serve the system only in so far as it expresses his vision of The Law. Where the chain of command fails to follow The Law he does not hesitate to defy it.

How The Law is developed is one of those world building gaps that I’m clueless about. Do we ever get to see judges disagree about the interpretation and application of The Law? I expect not, it seems likely that one of the gimmies of the strip is that The Law is utterly unambiguous.

Some people may be interested in trying to track down a weird little book from the late 1990s called The Dredd Phenomenon: Comics and Contemporary Society that “asks why it is that the most popular comic strip character in Britain is an authoritarian neo-fascist”.

Of course, I can’t remember if it’s actually any good or not…

Out of replies, but wanted to thank Carey for his/her kind words.

I feel a bit awkward sometimes writing about this stuff, because I’m not actually British, although being from Dublin I had a very close vantage point from which to observe Britain. We were reading 2000 AD, but it wasn’t being written for us, really. So I really would invite comment and correction from British readers.

Well, I’m of the mind that we’re all earthlets in Tharg’s eyes. In addition, when you look at the places listed before the planets, just below the price, a certain pattern appears. Just because you (and Jeff) are from nations which beat the rush on leaving the imperial party, I’m confident your groats are good.

Can we all agree that both the story and the character are called ‘*the* Judge Child’ rather than ‘Judge *Child*’? I twitch every time I hear the latter!

Whoops! That’s a solid correction, Arkady. Sorry, and thanks!

In reference to Graeme’s feeling that The Judge Child forseeing Dredd’s badge seemingly exploding in fire, is a cheat- it does kind of come to pass on page 4 of part 8, in the top panel, where The Fink hits it with his pizen stick (later a hit for Ian Drury & The Blockheads). Underlining the completely unreliable nature of The Judge Child’s visions, I guess.