Previously on Drokk!: Sure, Garth Ennis might be a well respected comics writer for work on titles including Preacher, Punisher, and Some Guy and A Gun or Something these days, but did you know that, when starting out, he wrote some really poor Judge Dredds? Because we sure do after the last couple of episodes.

0:00:00-0:02:32: Before diving into what is, ultimately, an uneven book — but one that’s far better than we’ve enjoyed in recent episodes! — we introduce ourselves, and the fact that we’re reading Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 18 this episode, featuring stories from 2000 AD and Judge Dredd Magazine from 1992 and 1993. Yes, there’s more Ennis, but there’s also more John Wagner than we’ve had for awhile, too, so… yay…?

0:02:33-0:34:59: As is our tradition, we immediately dive into the Garth Ennis material, because apparently we hate ourselves. Ennis writes all but one of the 2000 AD episodes in this volume, and we discuss the way in which these stories have all of his bad Dredd habits and then some, and Jeff floats a theory that, perhaps, editors were trying to position 2000 AD’s Dredd stories for the audience that was buying not-for-kids comedy comic Viz at the time. (I’m not convinced.) Also discussed: Mark Millar’s first Dredd story (it’s not good) and what it might owe to Pat Mills, whether or not Ennis has grown at all in how he approaches Dredd as a strip, and just why Garth Ennis’ sense of humor doesn’t really work in this strip, at least in this incarnation.

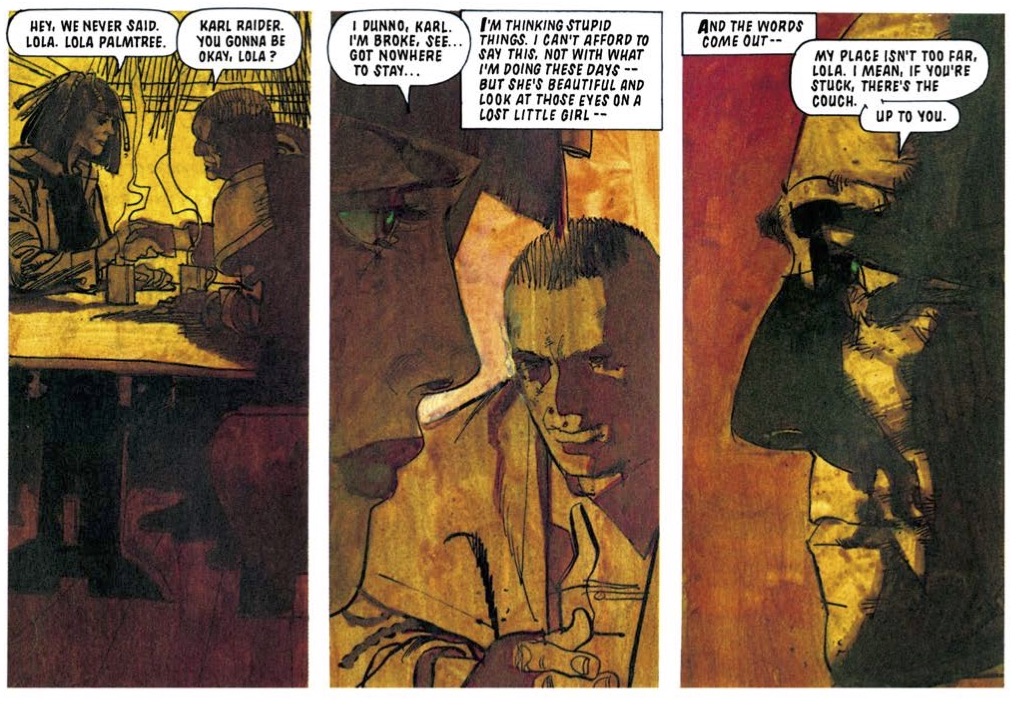

0:35:00-0:59:38: We’ve talked about Ennis’ seeming sympathies for the more fascistic parts of the Dredd mythos in episodes past, and we’re back at it now after Jeff talks about Ennis’ tendency to be a bully when it comes to the targets of his comedy. Is Ennis pathologically afraid of weakness, and if so, how does that factor into his support for might-makes-right as an ideology? We also talk about two storylines in which Ennis is at his most Ennis-y: “Raider,” in which someone is almost as hard as Dredd, but isn’t, and Ennis’ only P.J. Maybe story, in which he… utterly misunderstands the entire point and appeal of the P.J. Maybe character. Things are grim, Whatnauts.

0:59:39-1:01:22: Are the 2000 AD stories in this volume Drokk or Dross? Anyone who’s been paying attention wouldn’t be surprised that we’re not fans.

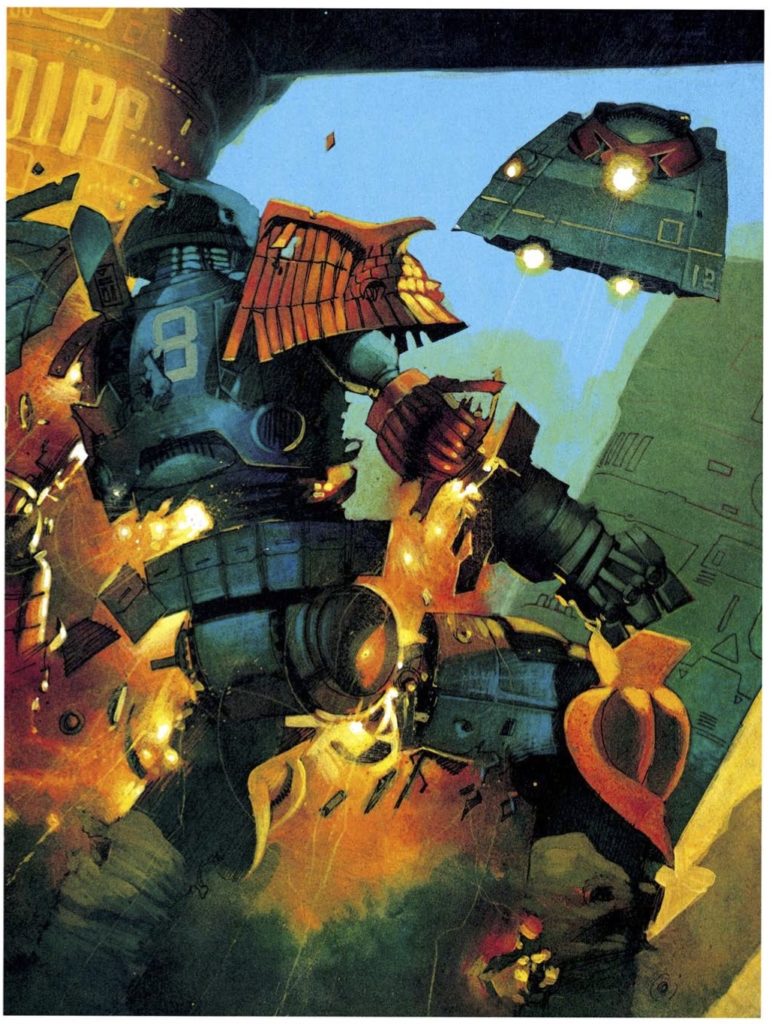

1:01:23-1:22:52: Onto the good stuff, as we get to the Magazine material, and “Mechanismo,” in which John Wagner asks the important questions: “What is policing without a human element?” and “What if I did a story based on that question but also referenced Robocop and Short Circuit, because they’re about robots?” Jeff also brings up good points about what the Mechanismo robots say about policing in 2020, and the ways in which John Wagner and George Romero have similar approaches to long form storytelling. No, really!

1:22:53-1:34:51: It’s not all “Mechanismo,” though, and Jeff raves about “A Christmas Carol” — both Dickens parody and statement of intent on Dredd’s place in the world by John Wagner, as it turns out — while we’re both confused and slightly non-plussed by John Hicklenton’s artwork on another of the strips. I’ll be honest, we pretty much shortchange the Alan Grant material in Case Files 18, but I think there’s also an argument to be made that we’re giving it exactly as much attention as it deserves. (Sorry, Alan.)

1:34:52-1:45:07: We start to wrap things up by looking back at the Magazine material as a whole in this volume, and then Case Files 18 in its entirety. Which is my favorite of the two “Mechanismo” stories in this book? Is the book Drokk or Dross overall? What are our favorite stories in the book? The answers can be found within!

1:45:08-end: And then we really wrap things up by looking at what awaits us next episode — Grant Morrison, and it’s not good — and by mentioning the usual suspects: Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and Patreon. Thank you as always for reading along and putting up with our meanderings, and I hope you’ll come back next month for an episode we’ll pretend is spookier than usual, because, you know, Hallowe’en and stuff.

Who would Have thought a slim pickings Case Files would provide such food for thought.

Jeff is, indeed, almost on to something when he argues that 2000AD was trying to position itself towards the audience that was buying Viz at the time (I was one of them). Graeme is bang on the money when he says that Ennis is reflecting the wider culture (aspects of which, if not coarse or vulgar, were low-brow). These progs were published between late-1992 and 1993 when the post-Second Summer of Love is slowly transitioning towards the Britpop era – Select magazine’s “Yank’s Go Home” issue would be published in April 1993 and the lads-mag bible Loaded would be published in October of the same year. Yoof magazine show The Word was a regular fixture for the post-pub Friday night schedule and was as coarse as catshit (yet strangely compelling viewing).

However, the real struggle 2000AD predicament with regards to readership was caused by the malign influence Simon Bisley’s art exerted on the British comic scene. Let me start by saying I loved Bisley’s ABC Warrior work at the time (and still do) and like a great deal of his work thereafter (the cover for Doom Patrol 57 with its malignant, scheming, crippled Chief still gives me chills). His painted artwork on Sláine was revolutionary and was used (along with the earlier British Invasion) as evidence that “comics were not just for kids anymore”. Nevertheless, two problems then arose: the readership began to demand and expect the same calibre of labour-intensive work on all the strips (very difficult, if not nigh on impossible, for a monthly or fortnightly, let alone a weekly) and much of the material published in a traditional boy’s action comic did not justify such lavish attention. Part of 2000AD’s charm was its cheap and cheerful punk aesthetic.

With regards to the art, it is interesting that the best stuff in this volume and the previous two volumes is produced by “seasoned veterans” Ezquerra, Burns, Baikie and Ron Smith who all had their own singular style, knew storytelling and pacing inside out and could meet deadlines. “Rookie” artists, like Staples, Power and Ormston were hitting the ground running, finding their feet on the job and still had to develop their own style (hence why so many of them were sub- Bisley clones – it’s what the market wanted – with many of his worst habits – too much detail on semi-clad women, sketchy backgrounds, lack of storytelling flow).

Incidentally, and worth noting in a sidebar in and of itself, the deterioration in the late great Brett Ewin’s art noted by Jeff was caused by his suffering serious mental illness (manic depression) which was diagnosed in 1991 This is discussed in greater detail in The Art of Brett Ewins (2011) published by Air Pirate Press. At the time, like many readers, I though this “flattened out” style was an artistic choice (like Mike McMahon’s later work).

With regards to the writing, would stories like “Ex-Men”, “Last Night Out”, “A, B or C Warrior” or “Blind Mate” have looked out of place rendered in black and white exclusively by Ron Smith in Case Files Vols. 5 – 7. Probably not. The woeful “Barfur” would have found its way into a Sci-Fi special or annual.

“Raider” It is, for the most part, pure pulp noir. And yet, I think, is a much more interesting story that our hosts allow. Raider was a recruit into the Justice Department. Although the choice was involuntary (presumably made by his parents when he was too young to decide for himself), he chose to leave for love. He obviously did not act on this love (unlike Judge Giant) while in uniform, otherwise he would be on Titan, and so could resign because he knew it would compromise his job. His “weakness”, women or “thinking too much”, is what makes him human (too human?) compared to a clone like Dredd. Too much humanity will get you killed on the mean streets of the Big Meg.

Dredd is, as much as he would hate to admit it, also human. He has “the doubts” like all “good” Judges. Wagner has established that Dredd’s trace humanity, an imperceptible x-factor, allowed him to transcend the genetic shortcomings of his bloodline (unlike the Juddah and Rico) and, ironically, continues to allow him the capacity for heroism and mercy. It accounts for Dredd’s ingrained suspicion of robots and dislike for hard-liners (Grice). Too little humanity robs you of perspective and you are unfit to be a Judge.

This is what makes Dredd such a compelling character. Under Wagner, the reader is asked to examine the minutiae of the slender pick of humanity within Dredd: Is there any “good” or “worth” in this Fascist? Ennis’ take has been much less nuanced and interesting: “Hard Men are Real Men”. Dredd is a Real, Hard Man, O.K.!

Is it possible that Jeff was thinking of Brendan McCarthy and not Brett Ewins? The two collaborated on earlier Dredd stories?

How you two are able to spin so much drokk from so much dross is a credit to your podcast-hosting skills, gentlemen.

I gotta start off by saying–you got me again! Last month I admitted to always thinking Strontium Dog was an actual canine. This time, however, Jeff got me when talking about Viz’s influence on 2000 A.D. and Ennis. I kept thinking, “Was Ranma 1/2 that popular that 2000 A.D. tried to emulate Rumiko Takahashi? I know that’s around the time manga was getting a foothold in the market, but…” Then I realized Jeff was referring to a British magazine, not Viz Media, publisher of translated manga. Can’t wait to see what I fall for next episode!

I did enjoy this volume on the whole much more than the previous two, and not only for the much needed return of Wagner. In this volume, I saw glimmers of the writer Ennis was on Preacher: still not good, in my opinion, but more coherent. (Didn’t Ennis have Jesse Custer’s cousin gut a fish and f*** it? Yeah, top-class writing there.) As our hosts pointed out, the dearth of Mega-City One characters or pastiches of the city that were such a hallmark of the Wagner-Grant years were solely lacking and to the detriment of the book. It’s much more fun seeing how Dredd involves himself in the lives of the citizens than being the one and only focus of the strip.

Thank you Winty for the deep dive on the Bisley clones. I was thinking about Bisley and his apparent influence in this volume, whether taken upon themselves by the artists willingly or mandated by editorial. You answered a lot of my questions! It’s a shame that aside from the Batman crossover, Bisley never really drew Dredd proper in 2000 A.D., at least to my knowledge. Guess I’ll have to settle for the knockoffs.

I also agree with Winty that some of these stories could have slided into Case Files Vols. 5 – 7 if drawn in B&W by Ron Smith or Mike Machon. Of course, they still don’t feel entirely like they’re set in MC1, and many of Ennis’ stories just end too abruptly for my taste, as if he reached the end of his page count and said, “Well, no time to rewrite it to fit it in, so I’ll just let it go as is.” Maybe he was too used to U.S. comics with their more generous page counts?

The “Mechanismo” stories were definitely my favorite in this volume, and I was really struck by the Ouroboros-ness of it. Dredd influenced Robocop, and then Robocop influenced this story, it would seem. The catch copy on the back cover of the print edition even proclaims “Rise of the Robocops!” While a few years out from the original, these stories came out right between 1990’s Robocop 2 and 1993’s Robocop 3, which put the character very much in the zeitgeist, along with sequels to the Alien, Predator, and Terminator franchises. (Robocop 2 and 3 were also quite notorious in the comic fan community for having been penned to some degree by comics own Frank Miller.) The plot of 2 even revolves around the corporation trying to make more robot cops like Robocop but only succeeding when they hit on the idea of using a drug dealer’s brain. If that’s not a Judge Dredd story in all but name, I don’t know what is.

Finally, is there any writer working in comics who has more contempt for their audience than Mark Millar? You can practically hear him laughing scornfully at the reader behind his turgid dialogue.

I was curious to see what you would think of Mechanismo, because you’ve liked to read Dredd from the standpoint of science-fiction, and one thing about it is that I think this is Wagner trying to do actual science-fiction more than in any of the “big” Dredd stories before this.

I think it makes a strong contrast with the Robot Wars especially (OK, way back when). Those robots were in no sense meant be actual robots. They were funny metal people and metaphors for the working class. Whereas these robots are meant to be actual machines. The *reason* why they malfunction is, umm, not perhaps informed by the most up-to-date grasp of information technology. But there is a technical reason, which gives the story a vague hard sf air.

From this perspective, it is maybe a problem that the first Mechanismo story is a bit of a clichéd Robots Gone Wrong! romp, because *as* a science-fiction story this was already terribly hoary and dated. I tend to think that in this context it seems better than it is, because (as our hosts discuss) the art is wonderful and it’s good to have Wagner’s reliable storytelling competence back. I think our hosts are right in that the interesting stuff here is about the idea that the robots are modeled on the idealized image of a judge that Dredd himself projects and (presumably) enshrined in his book. Once again, we might be able to detect Wagner’s discomfort with his own creation, with the way in which Judge Dredd can so easily be read (and is, in fact being so read by Ennis) as an idealized model of right-authoritarian unflinching and unbending enforcement of the rules as an unequivocal good thing.

There’s a suggestion here that what is important about Dredd is that his “Comportment” is a pretense, an act – that he knows that, if it came down to it, what would matter is that he would have the capacity to *break* the rules in a way that no robot could. The problem is that it’s really no more than a suggestion, even in the second story – Wagner doesn’t really do anything with that idea.

I was surprised to hear you didn’t care for (and quickly dismissed) “Unwelcome Guests”, which I thought was the best Ennis story for actually turning a mirror to the judges and their practices. Well of course the regular judges aren’t going to like the SJS. And of course the judges are hyper-alert, always ready for a threat, and you can easily imagine “let’s jump this judge without warning and randomly abuse them” could go very wrong, very fast if the SJS gets careless… which they did. It left me nodding and going, “Well of course that’s exactly what would happen.”

[This is meant as a reply to Matthew. Threaded responses don’t seem to be possible for me at the moment for some reason.]

I think you’re right, and that it makes sense for the regular judges to dislike the SJS. For that matter, it realistically makes sense that if the SJS bursts into judges’ homes in the middle of the night, this sort of thing is going to happen, by the normal rules of Dredd’s world. It’s what logically probably should have happened in the original Wagner & Grant story.

But I think the other side here is that it’s missing the point of the earlier story, which is that it’s a depiction of the system. And Dredd believes in the system and its rules – in the original story, there is no hint that Dredd would disapprove of this routine procedure of checking up on judges. This converts him into something that is approaching your classic cop “who doesn’t play by the rules, but gets results.” In fact, it is very much your standard trope of the “real police” vs Internal Affairs that’s familiar from a lot of police dramas.

And it’s part of what our hosts are viewing as Ennis’s leanings towards fascism and I would locate in something that was more directly relevant and still ongoing at the time, Northern Ireland – that sense that what you really need is to let the violent man be free of the rules and do his job.

Which is an impulse that led the British security forces in NI to some pretty dark places. I say that as someone who ultimately thinks the broad position of the British state in the Northern Irish conflict was generally in the right. But the details – some of those don’t reflect as well on it. Part of why I push back against “Everything is fascism” in this context is that I think it sweeps under the carpet real things that people did, that should be remembered and were 100% relevant at the time.

While we’re on it, since Jeff Lester raised the question of whether Ennis can be Protestant if he’s an atheist – the answer is yes, in an Irish context, absolutely he is. It’s about which community you belong to, not whether you are actually a believer. David Morris laid it out a while ago – it’s how you can be placed by a series of questions, like “Where did you go to school?” You can compare it in an American context to how someone can still consider themselves culturally Jewish and identify as Jewish if they are not in any way observant or believe in God.

This is more than a little parochial, but Killester? First we had Raheny, now this. At this point, no specific location in any British city has *ever* been namechecked in Judge Dredd, but we have two, count’em, two areas in north Dublin, neither of them especially famous. I have to guess that Ennis was maybe aware of the general stereotype of the Northside, and after that threw darts at a map? If I were a devoted 2000 AD reader from, I don’t know, Hull or Aberdeen, I might be feeling a little aggrieved.

An example of how the Catholic/Protestant cultural/community stuff that Voord mentioned affected a multitude of different aspects of life in Northern Ireland is how one specific letter (“H”) is pronounced.

“The two variants used to mark the religious divide in Northern Ireland – aitch was Protestant, haitch was Catholic, and getting it wrong could be a dangerous business.”

https://www.theguardian.com/science/shortcuts/2013/nov/04/letter-h-contentious-alphabet-history-alphabetical-rosen