Previously on Drokk!: Mega-City One has been invaded by Dune Sharks — something that seemed a little out of the blue in the last volume of the Case Files, but will have big repercussions this time out. Meanwhile, John Wagner has settled firmly back into being lead writer on 2000 AD’s Dredd, but the Magazine’s revolving line-up of writers is continuing to struggle in finding the right tone…

0:00:00-0:02:31: This time out, we’re talking about Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 26, which covers material from 1997 — namely, 2000 AD Progs 1029-1052, and Judge Dredd Magazine Vol. 3 #s 19 through 33. As we say right from the start, it’s another uneven volume, but that’s not necessarily as bad as it sounds, as we get to soon enough…

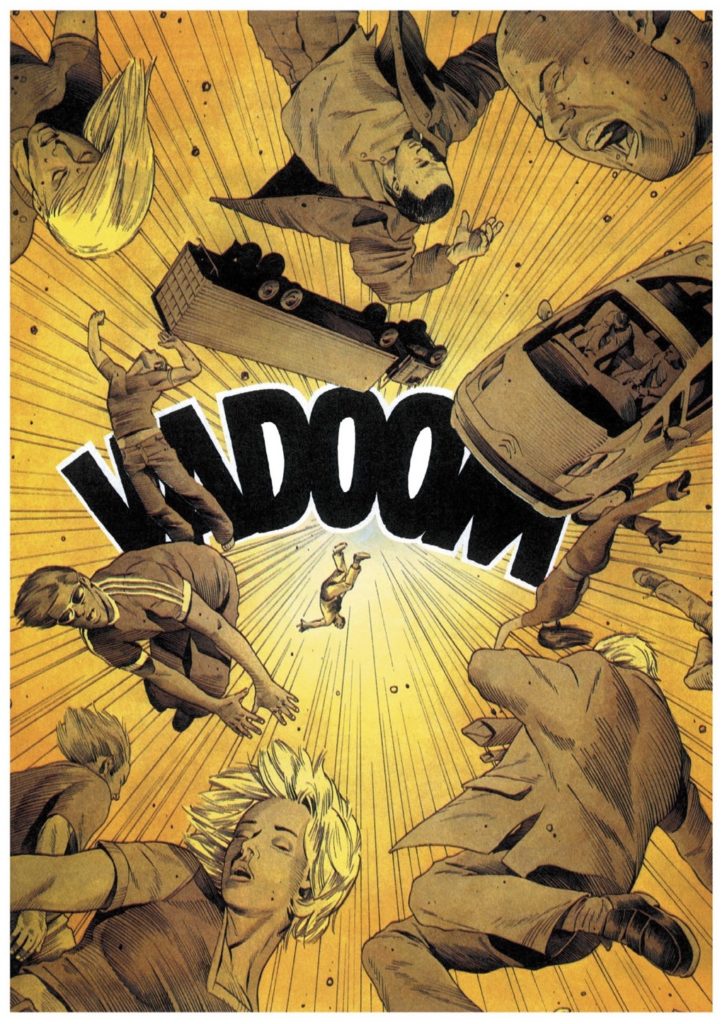

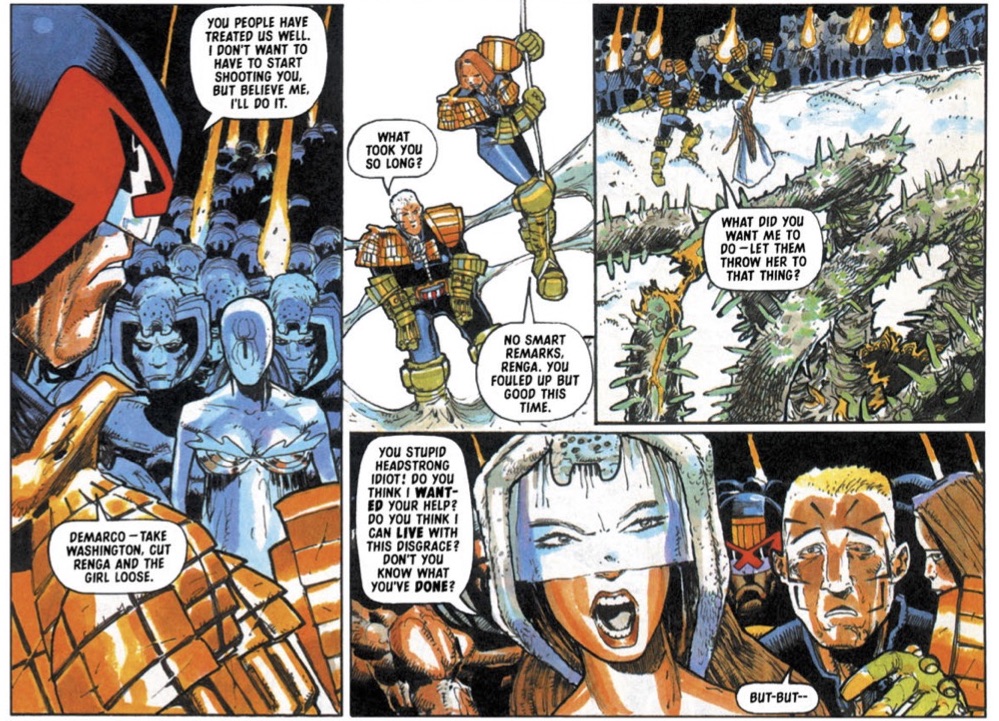

0:02:32-0:48:08: Almost immediately, we start talking about the extended storyline that takes up the majority of the 2000 AD episodes, in which Dredd, Demarco and a bunch of cadets go hunting for the origins of the Dune Sharks from the last volume; it’s a storyline that changes the way I look at Dredd as an extended comic strip, and maybe not in a manner that’s necessarily logical; Jeff doesn’t quite agree with my viewpoint, and we talk about that, as well as about the extended storyline as a whole, and what it owes to previous Dredd stories — in particular, “The Judge Child Quest,” “The Cursed Earth,” and “Wilderlands.” (Another unexpected echo that we discuss briefly? 1960s Star Trek.)

We also talk about the ways in which this extended story fails, whether it’s in the unexpected plot hole lampshades seemingly needlessly by a revelation in the story’s climactic arc — one that makes things “practically Chris Claremont-esque,” according to Jeff — or the meandering nature of each individual serial inside the larger story… something not exactly helped by some unfortunate art choices. (Who knew nuclear apocalypse could be so underwhelming?) As we talk about art, I explain my love of Henry Flint, which is likely going to be a recurring theme now that he’s shown up as a semi-regular on the strip. All this and Jeff’s food analogy for reading this book!

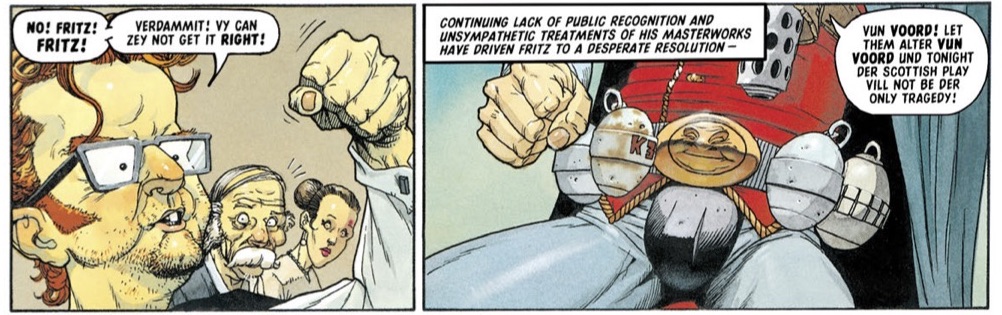

0:48:09-1:11:35: It’s not all hunting after Dune Sharks, though; there are a handful of other 2000 AD stories in this volume, and we go through them quickly: “Mad City” is a trifle, but distinguished by a strange Chris Evans (no, not the Marvel actor, this one) connection and some lovely art from Greg Staples, whom we both enjoy; “The Big Hit” is Mark Millar, and therefore terrible; “Lonesome Dave” manages to transcend the pun at the heart of the title thanks to some great John Burns art; and “He Came From Outer Space” has a great opener but otherwise disappoints. We also talk about the value of Dredd that’s just fine (Wagner’s “phoning it is… better than when some of the new guys are trying to bust their ass,” as Jeff puts it), as well as the effect that every episode of Drokk! has on me — and why Jeff should start reading the Case Files a little earlier each month.

1:11:36-1:22:15: If 2000 AD’s Dredd is in reasonably strong shape, the same can’t really be said for the Magazine; as we rush through the majority of the stories there, we sound admittedly pretty dismissive, but I’d argue that we’re being entirely fair. Could the problem be the Meg itself, we ask?

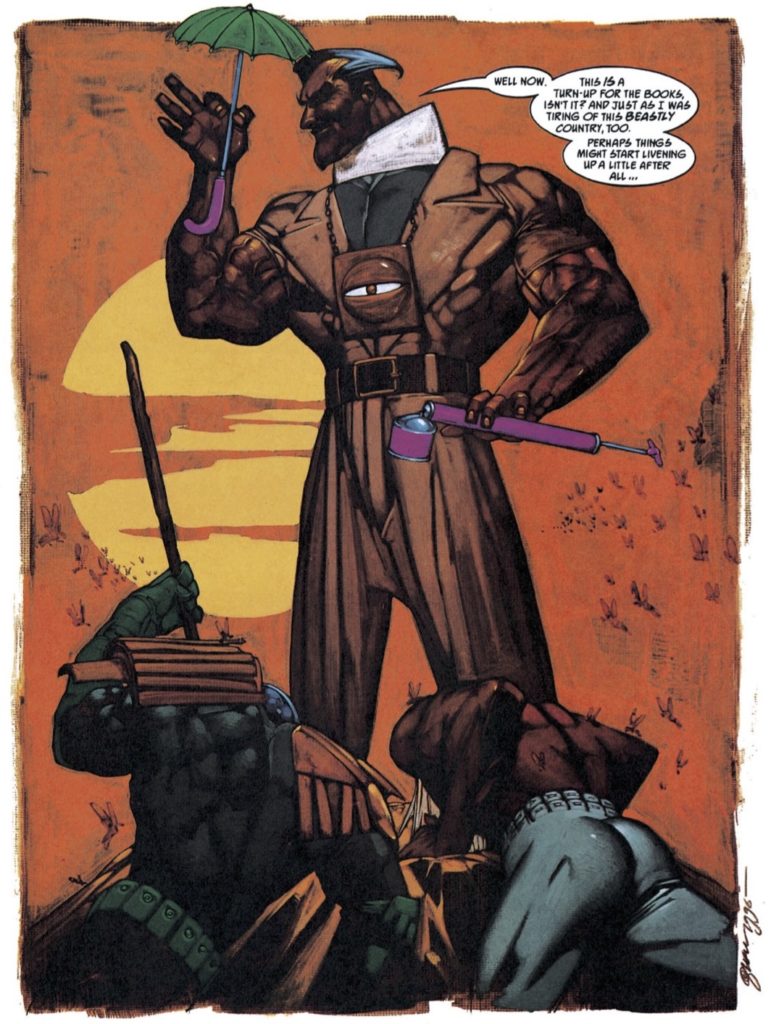

1:22:16-1:52:10: Understandably, we spend a lot of time talking about “Fetish,” the second-longest arc in the book, and the major contribution from the Magazine, as John Smith and Siku team up to create something that’s part-impressive, and part-racist mess. Despite the problems with Siku’s atmospheric-but-lacking-clarity paintings and John Smith’s lyrical-but-“Simba-City”-what-the-fuck-is-that writing — if you think that’s bad, wait until you hear us discuss the closing caption — there are things to appreciate in this near-Mega-epic, not least of which the appearance of Devlin Waugh, who steals the show despite not actually accomplishing anything on a plot level. It’s Jeff’s introduction to the character, and we talk about that briefly, as well as a short discussion about double page spreads and whether or not the (many!) in this storyline are successful.

1:52:11-end: It’s time for that question again: Drokk or Dross? We both plump for the former, and choose our favorite stories — Jeff goes for “Fetish,” and I kind of hedge my bets between “Lonesome Dave,” “Dance of the Spider Queen,” and “Trail of the Man-Eaters,” but what do you expect from someone who was also convinced we’d been recording for 30 minutes or so longer than we actually had? (In my defense, there were technical issues that threw me off.) While talking about our least favorite stories, we also ask a question that I think had been circling all episode: Is 1990s Judge Dredd the most racist yet, and if so, why?

After that, it’s time to wrap things up, look ahead to the next episode, and tell everyone about our Twitter, Instragram — even though I got the URL wrong; it’s waitwhatpod, not waitwhatpodcast — and Patreon. As always, thank you for listening and reading!

And for those who want to copy and paste the link directly, https://theworkingdraft.com/media/Drokk/DrokkEp29.mp3

Yeah, this was okay. I disliked Fetish more than either of you, but I was reading it on a tablet without the special program, so I didn’t really give it a fair shake. Liked Flint’s art. I see some O’Neill with the McMahon. It’s a substantial debt, but he’s integrated his influences successfully enough that it looks like a whole and not a collage.

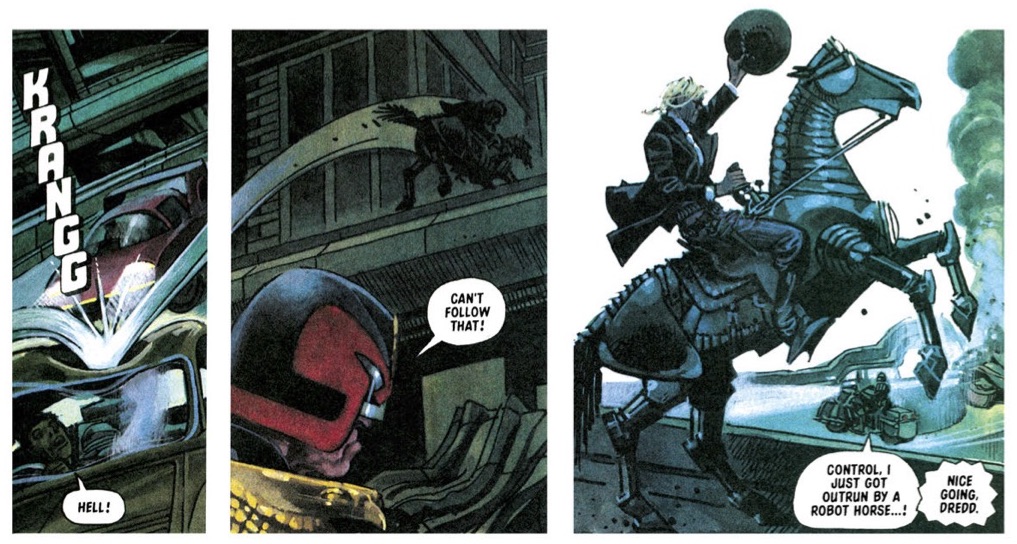

Perhaps, a little sadly, my greatest pleasure from this volume was being reminded of Nick Jolly. Like Lonesome Dave, he had a robot horse, but his could fly! And travel in time – I think. Given to him by aliens. Ron Smith drew it. DC Thomson’s comic. On that, does anyone know why Commando comic has increasing numbers of women lead characters? I don’t know how long this has been going on for, but I’ve noticed this year that there have been quite a few. I see them on Comixology, it’s become an odd fascination. Is it working for them? Have they found an audience for women’s war-time adventure?

FWIW I had no issues reading the double page spreads on landscape mode in the 2000 AD app itself.a

Hey guys, Warriors was indeed a re-purposed newspaper strip. It was my first pencilling and inking gig, the excitement and pressure of which nearly killed me! It was drawn for black and white and I had mixed feelings about seeing it coloured, chopped up and pasted into the dullest ever 90s full page layouts.

This is how it was meant to be seen!

http://jackcouvela.blogspot.com/2011/01/judge-dredd.html

Jack: so sorry your comment hung in moderation for so long. Thank you for the context and the link—the art looks great!

Well, well, well. I tucked into this episode relishing the moment when you would begin tearing “Fetish” a new one. I can’t even begin to describe the utter betrayal I felt when you both not only said you liked it, but Jeff chose it as his favorite in the whole book!

I knew “Fetish” was going to be bad–for me–from it’s very first word: “Africa.” British comics writer in the ’90s? No way this story doesn’t hop on the racism train and ride that thing off a cliff. I wouldn’t go as far as to call it pretentious, because I think there some genuine heart under the surface, but it was self indulgent and self important in the extreme. As soon as I started reading, I thought Smith had spent a long weekend with some illegal substances and the Lion King soundtrack and Toto’s “Africa” on a loop, and sure enough a few pages in we get “Simba City” and the worst pastiche of African tropes I can recall. He even name checks “The Heart of Darkness” at one point, because OF COURSE that’s what you do with a story set in Africa. Even when the Case Files have been at their most dire (*ahem* Millar, Ennis, Morrison progs), I have never wanted to close the book and throw it across the room as much as I have when reading “Fetish.” And of course it’s titled such, because Smith can’t help but fetishize Africa. Also, how did so much African fauna survive the nuclear apocalypse intact and unmutated? Was Smith so desperate to tell this story he just decided to throw out all of the world building in Judge Dredd? I’m pretty sure most of those animals have been declared extinct at various points in Dredd’s history.

And don’t get me started on the art. Did the editor say, “Give me someone who does a really bad love child of Bill Sienkiewicz and Simon Bisley and let them have at it for 90 pages”? Every now and then there’d be something to recommend it (landscape, Devlin’s car), but any time there was sequential action, I had to break out a protractor and a magnifying glass to figure out what was going on. Straight-up cartooning is not Siku’s strong suit.

The only pleasure I derived from reading “Fetish” was being done with it and imagining what the two of you would have to say about it. Since I was robbed of the latter, I’ll take some measure of consolation in venting here in the comments.

I will say I did enjoy the discussion around what it means for a Dredd story to be merely fine, and what is the platonic ideal of a Dredd story. For me, good Dredd reminds me of a good Twilight Zone episode: You have the premise/set-up, some kind of twist, and some theme or underlying social commentary binding it all together. The most disappointing episodes of TZ were when the premise was the whole episode, and there was nothing deeper or richer about it, or no twist or circumvention of expectation. Since I’ve been reading along with you from the beginning, something like “The Apocalypse War” really set the bar high for that, and I think it reached an apotheosis in the journey from “Letter from a Democrat” to “America.” Now I love me some of those disposable Wagner/Grant tales from the early years, and I still enjoy them when the come along and are competently told and illustrated. But damn if I didn’t want to see what Wagner would have done and had to say if he had followed through on the democracy movement. Maybe the strip wouldn’t have survived it, but I don’t personally need the strip to go on forever, especially with a main character who ages more or less in real time.

Finally, about the resurgences (return to openness?) of racism in the ’90s, I think part of it is was Jeff said with that attitude of “We’re all post-racial, so can’t you take a joke?” The other part is, as many people have pointed out recently, is that whenever an oppressed group makes strides in equality, the establishment feels threatened and pushes back. (Look at all the voter suppression in response to BLM or the TERF movement in response to trans rights.) In the ’90s, Black culture, particularly pop culture, was ascendent. Some of the most popular sitcoms (The Fresh Prince, Martin) featured all Black casts; the most popular athletes, at least in America, were Black; fashion trends started by the Black community became de rigueur for suburban white kids; and, probably most importantly, hip-hop and R&B were truly ascendent and mainstream in the ’90s. Rap was no longer just a trend for urban youth–rap was everywhere, to the detriment of rock ‘n’ roll. In 1997, we’re only a few years away from NuMetal bands co-opting rap and making it white, for lack of a better term. Looking back now, I can see the outsized negative reaction to hip-hop for the racism it was, even if at the time those haters couched it in terms of not liking the genre of the music itself. The establishment felt threatened and had to push back, and what we got was racism under the guise of comedy, discrimination under the guise of criticism (as in critical analysis), and hate under the guise of “I’m just punching up with my social commentary.”

The appearance of Chris Evans and the discussion around Fetish brings up a point that I always feel is overlooked in these discussions: the role of the editor. This volume very much highlights the dangers of reading Judge Dredd in isolation (beyond the Thrill Power Overload that Jeff is experiencing!) as 1996 and 97 were problematic years for 2000ad, having been hit hard by the failure of the Stallone film. The best illustration of this is how there was a running joke in the UK comics community at the time revolving around the question of what 2000ad would be called after the turn of the millennium, with the answer being “cancelled.”

Into this stepped David Bishop, who from all accounts was a very hands on editor who could be brutal when he wanted to (best exemplified by his rejecting a Frank Miller cover for an anniversary Megazine because it was substandard). He implemented several strategies to gain media attention, including writing out Tharg as editor and replacing him with “The Men In Black” (to appeal to the X-Files phenomenon happening at the time) and “guest appearances” by celebrities such as Chris Evans. The nadir of this approach was the infamous Prog 1066, aka the Sex Issue: http://progslog.blogspot.com/2010/02/prog-1066-281097.html

An attempted to appeal to the Loaded/Viz audience that simply resulted in the comic being stocked from that point onward on the top shelf at British newsagents next to the adult magazines. Never before had anyone thought of the crossover potential between 2000ad and Readers’ Wives…

For all this, Bishop was arguably responsible for keeping 2000ad alive during this period until the point came when Rebellion would buy it, so he must have done something right. And Bishop was himself answerable to executives who, according to his own book were very money conscious and disliked cancelling projects, which makes me wonder whether that was the reason for Fetish’s disjointment and terrible last page, as by the introduction in the tpb that Graeme read, it was something that not only went through many artists but also many rewrites. Was the “white man’s spirit” line something Smith wanted to put in, or simply giving into editorial suggestions? My own reading is probably it was something lost along the way: as others have said, well intentioned criticism of the west’s attitude to Africa that landed in a totally tone deaf manner.

For all his self indulgence at time (hello Vertigo’s Scarab) Smith was, in my honest opinion, the best writer at 2000ad during this period (Wagner excepted). With this in mind, I’d very much love a side episode of the two of you reading Devlin Waugh: Swimming in Blood (with beautiful painted Sean Phillips art) and Chasing Herod (with beautiful Steve Yeowell art), both of which come across as less constrained/problematic Smith.

I quite like those Waugh stories that Carey refers to, but can’t shake the feeling that Smith is constrains himself with Waugh. That they’re a satire of blockbuster movies and he amuses himself (and me) with the central character to escape the tedium of a story with a beginning, a middle and an end.

Just providing a link to the review/discussion Graeme did of the Devlin Waugh comic with Douglas Wolk back in 2012. It provides more context for the Fetish story in case anyone wants it.

http://dreddreviews.blogspot.com/2012/02/devlin-waugh-swimming-in-blood.html

Scattered thoughts:-

– I have to agree with Miguel Corti about our hosts being too easy on Fetish. Which is honestly something that I find a little curious. Perhaps I need to listen to the episode again, but it didn’t come across to me all that clearly what the positive virtues of the writing were supposed to be that compensated for the story’s flaws, aside from having Devlin Waugh in it, eventually. I’d have to agree that Fetish became better when Waugh showed up, but it had a lot of room to become better without being particularly good.

And, for fairly obvious reasons, putting Waugh in Meant-To-Be-Positive-But-Horribly-Generic-And-Uninformed-In-A-Racist-Way Africa immediately turns up the Victorian Boy’s Adventureness of it all in a manner that may have been meant to be ironically self-aware, but just shows up how little there is here that isn’t good old fashioned imperial tropes.

Plus, this is a personal taste, but in a story with this little to it, language like ”Zebra hides strobing under neon strip-lights. Lips skinned back from yellow teeth. The smell of urine and dung and jungle.” just comes across as a desperate attempt to put a literary gloss on the fact that there’s nothing here that’s thoughtful in a more substantive way.

– Millar’s The Big Hit has, for me, that quintessential Millar quality of being incredibly crass and awful, and yet having that little thing in there that’s interesting, as if Millar puts one thing in every story in just to taunt the reader with the fact that Millar could be better, and doesn’t want to be.

In this case, it’s the basic premise of a Justice Department hitman who goes around carrying out extrajudicial killings. Except they’re not extrajudicial, are they? They can’t be. Because the whole point of the judges is that there are no trials and they make summary judgments.

By injecting something that is so obviously reminiscent of the extrajudicial killings carried out by real authoritarian regimes, the story points up how artificial the way that Dredd’s world works normally is, and how we accept it only because it follows narrative conventions of a police story that we have been taught to accept. Dredd acts as a cop most of the time — something happens, he responds to it. It’s all very reactive. At the end, he issues a sentence.

In other words, Judge Dredd might be called a judge, but he’s not: he’s a police officer. Specifically, he’s a specific right-wing fantasy of a police officer, one grounded in a familiar police-story trope. It’s that recurring motif where the police officer catches the criminal, but the court lets the criminal off “on a technicality.” Judge Dredd is a fantasy of the police officer who doesn’t have to deal with that, and can just go straight to the “They’re guilty” bit. (This is obviously a place where the fact that all Mega-City One citizens are white, and the only black people are judges, is doing a lot of work to sweep things under the carpet.)

But there’s no reason why the system should be that reactive. Why wouldn’t judges just get together in a room by themselves and issue a verdict, and then send someone out to execute the death penalty? That’s the logic of the system. But it doesn’t feel like law, does it? It feels extrajudicial. Millar has hit on something that destabilizes the core concept of Judge Dredd.

And then he does absolutely nothing with it, and instead is horribly racist.

More scattered thoughts:-

– I was inclined to be a bit easier than our hosts on the The Hunting Party (etc.) series of stories. I think one can see Wagner trying to feel his way ahead. He’d gone off in the direction of soap opera, an ensemble, and Judge Dad in The Pit — but then followed that by going back to very traditional Judge Dredd in the next few stories. The Hunting Party came across to me as an attempt to integrate the kind of thing he had done in The Pit with trad Dredd, to see how some of the oldest things in Dredd look if you combine them with a focus on supporting characters and a softened version of Dredd himself.

It’s also, and I am a very easy mark for this, got a lot of that thing where the Cursed Earth allows for an exploration of America from a British perspective. We’re back to doing Judge Dredd as a Western. This is one of the things where the presence of a cadet from Brit-Cit is interesting, because it reminds us that Mega-City One is supposed to be in America, while previous Cursed Earth stories tend to default to Dredd as implicitly somehow British in contrast to the Americana of the Cursed Earth.

This is where I wonder a bit about whether Wagner realized that he only had so many stories about that. We have Americana, which sets up the theme. Then we have Fog on the Eerie (incidentally, does John Wagner know that Lake Erie is, er, a lake?), which is again a solidly American setting. Further, it’s subtly updating the original nuclear-war origin story for Dredd’s world to suit how history had gone on: now the war happened in a unipolar world in which all the other countries reacted to the US. The spider story skips the Americana theme, but it’s back for Camp Demento.

Camp Demento, I thought, was a much better story than our hosts did. To start with, it’s not accidental that it’s set in Michigan. It’s a reference to the Michigan Militia, which became notorious when awareness of militia groups rose in the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing. So this is a story that’s addressing something of contemporary relevance, and while it’s not exactly subtle in what it says about American far-right culture and its unfortunate combination of gun fetishism, militarism, and paranoia — it’s not wrong, is it, and since when has 2000 AD had to be subtle to be good? Making the militia counterparts children is a particularly nice touch, because there is something essentially childish about this outlook, seeing as it does a world divided neatly into goodies and baddies.

Further, I don’t think it should be read in isolation, but as the counterpart to Fog on the Eerie, in which an insane American President brings about disaster for the world. We come back to unipolarity: this is a pair of stories that are steeped in a worry about the world’s only superpower, with the ability to pave other countries over with radioactive glass at a moment’s notice, having this particular strain in its culture become more and more dominant.

The Americana theme mostly vanishes in the last story. In fact, the funny robot villain (why yes, this is a trad Dredd story) of the piece is coded as British. (“Diabolical cheek.”) That being said, there’s good stuff here, when the robot, who seems so self-aware, just shrugs with “How should I know?” when asked what the point was, prompting Dredd to comment, “I guess we’re all just robots under the skin.” That’s a fascinating line, because it up-ends the joke about the robot just being a robot after all. I think it picks up on Stark’s sharp observation in Camp Demento that the children there were subjected to something much like the Academy of Law.

– A story that I don’t think our hosts said all that much about is Zero Tolerance. This has not aged well, because it’s overtly about the “broken windows” theory of policing (because yes, this is 1997) — and it presents it as being right, the thing that saves us from a monster like Tyrell. Also interesting in that “promiscuity” (which apparently means adultery) is a crime in Mega-City One, which I think is a mistake. The joke in Dredd is not that things that aren’t like crimes in our world are crimes, but that everything is exaggerated. Littering carries a serious penalty, sugar and coffee are regarded as dangerous illegal drugs, and so on: it’s all rooted in something that we recognize.