Previously on Drokk!: The Apocalypse War ended two volumes ago, but it perhaps should come as a surprise that the aftermath of nuclear conflict takes awhile to work itself through. The real surprise may be that writers Alan Grant and John Wagner make it seem so entertaining…

0:00:00-0:01:31: Speedier than usual — and more scattered, because someone (it’s me) has forgotten how we normally start these episodes — we introduce ourselves as well as the fact that, this episode, we’re covering Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 7, which includes episodes from 2000 AD Prog’s 322-375, publishing in 1983 and 1984.

0:01:32-0:11:31: Jeff and I disagree on what the defining feature of this collection is; for Jeff, it’s comedy, for me, I’m struck by the existential horror that life in Mega-City One has become by this point, calling these stories “bleak in ways the series has never been.” Perhaps that’s why Jeff thinks that this is the closest the series has gotten yet to the platonic ideal of Dredd as a strip in his head — or maybe it’s the level of craft on display in these stories, as Wagner and Grant continue to push at the edges of what Judge Dredd as a comic can be.

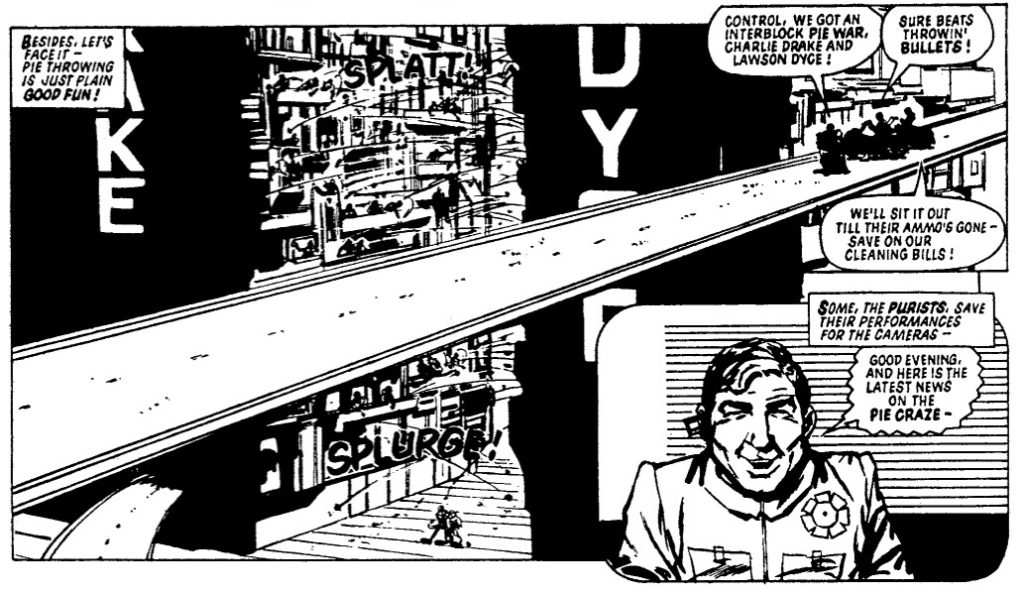

0:11:32-0:24:35: We talk about the fact that, in this volume, Mega-City One feels more out of control than ever, and also about the grim humor — and perhaps misanthropy — that propels so much of the writing in this collection, whether directly, as in the “High Society” one-off story, or obliquely, as in a story in which the public votes an orangutan into office. This is a volume in which Wagner and Grant seem to be becoming more interested in Mega-City One citizens than they are the titular hero, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that they like them.

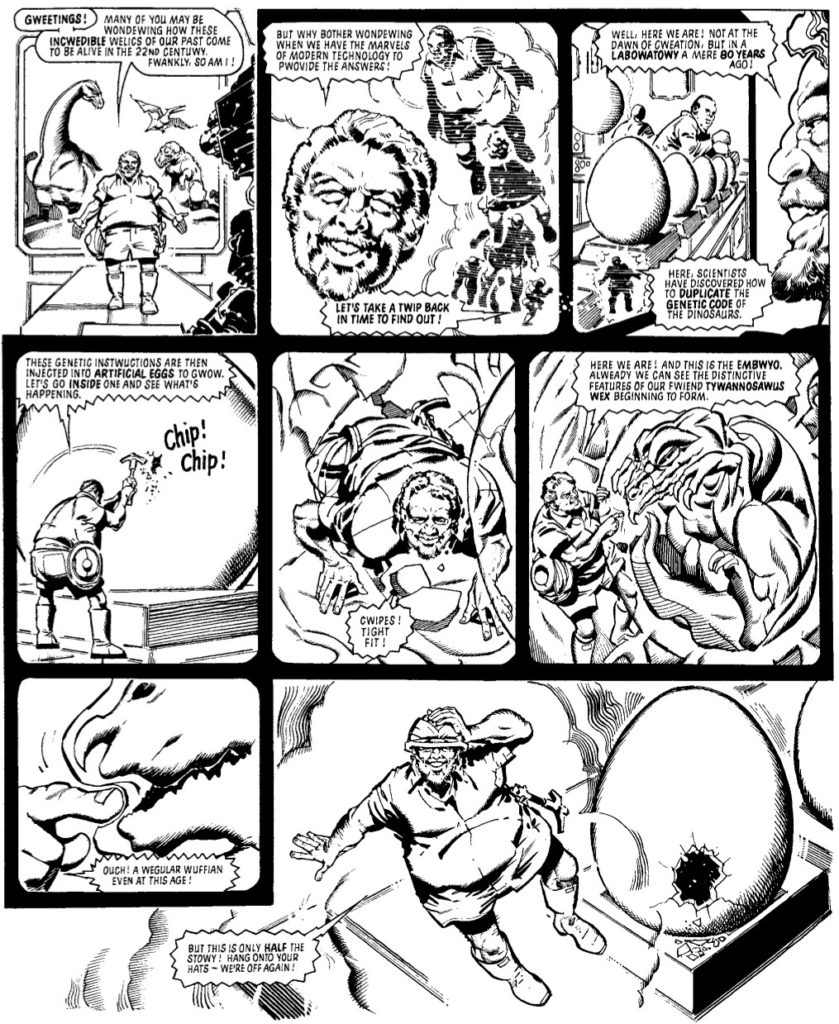

0:24:36-0:32:47: All of that leads us into a discussion on world building, and how seemingly effortless it’s become by this point — even when such world building seems to overwrite what other creators (Pat Mills, ahem) have done earlier in the strip. Or is it just reinforcing what has come before?

0:32:48-0:49:16: By this point in the run, Judge Dredd as a strip — and Wagner and Grant as a writing team — have perfected the idea of writing for multiple audiences at once, which means that Jeff and I talk about the multiple layers to be found in these stories, whether it’s literary shout-outs or an unexpected number of superhero references that are found in this volume in particular. Are there implicit digs at Alan Moore to be found? Are Wagner and Grant just entertaining themselves as they work their hearts out? And what does this do to tonal whiplash, versus tonal consistency? All is under discussion!

0:49:17-1:05:47: Just how prescient is the strip at this point? I say that it’s feeling far more in tune with the world today than I expected, or necessarily am comfortable with — shades of how Jeff was feeling last episode — and we end up talking about what Jeff calls the “uncanny valley” of topicality in the strip, and how much of it is actually predicting the future, versus just paying attention to humanity and history.

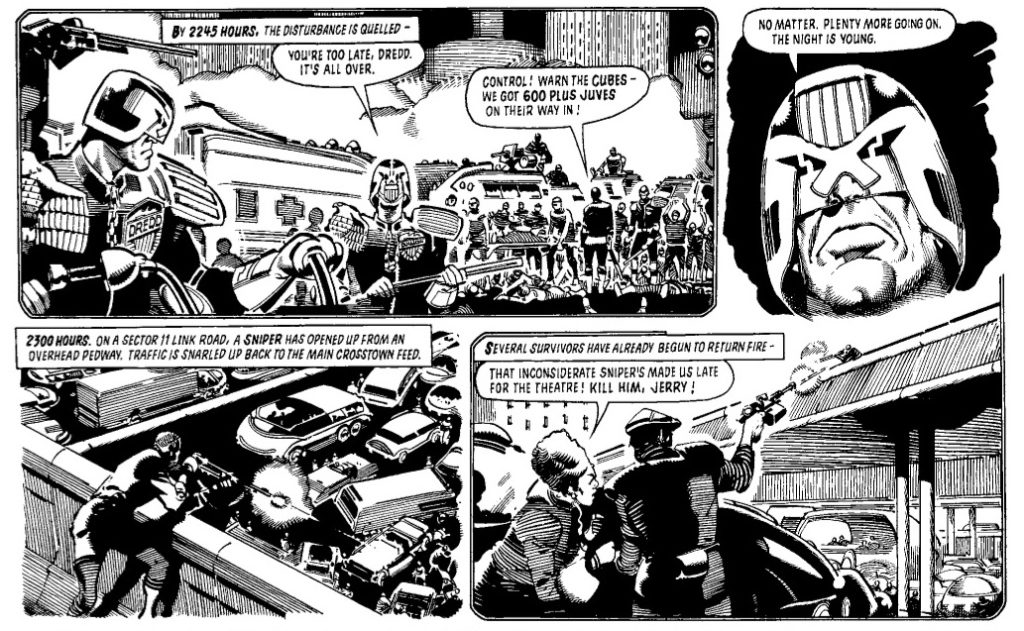

1:05:48-1:28:03: We talk about “The Graveyard Shift,” the seven-episode storyline that seems to be the heart of this volume, and just how overwhelming it is, as well as what it does in terms of world building but also character building for Dredd and for Mega-City One as the most obvious supporting character in the strip. Plus: How funny is this volume?

1:28:04-1:38:46: From “The Graveyard Shift,” we go to another handful of storylines in the book, whether it’s “Citizen Snork,” “The Haunting of Sector House 9” or the untitled training of Rookie Judge Decker that closes the book out, and delivers a great character both of us hope we see again. But: is the fact that Judge Dredd as a strip seems like it can actually do any kind of story what gives the strip its power by his point? Jeff suggests that’s the case, and as usual, he’s probably right.

1:38:47-1:47:03: This is, once again, just a great looking book, and we talk about that: The presence of Steve Dillon, Brett Ewins and Cam Kennedy can’t be overlooked, and the variety of visual styles on display is something that Jeff feels particularly strongly about. So much so, in fact, that he won’t let me complain too much about Ian Gibson. (It’s such a good looking book that Ian Gibson is the weak point. Just think about that!)

1:47:04-end: Attempting to close things out, I have a couple of final questions: Are the Judges seeming different in the book — because they seem kinder to me at a couple of important moments — and what are our favorite stories? For Jeff, it’s “Haunting of Sector House 9,” and for me, “The Graveyard Shift.” We briefly talk about the fact that Wagner and Grant’s shockingly heavy workload at the point these comics were being produced might have made them even better writers, and then we wrap up by mentioning the usual Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and Patreon links to visit. Next month: Vol. 8, and an abandoned mega-epic awaits! As usual, thank you for listening and reading.

And for those of you patient enough to wait for a direct link… http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp7.mp3

Was just looking through the covers of the issues in this volume, and found the one for 359 kind of hilarious.

2000 AD

Featuring Judge Dredd

Presents

The Haunting of Sector House 9

Starring Judge Dredd

[Cover features large drawing of Dredd complete with readable “Dredd” judge badge.)

[Spoilers for the future of Judge Dekker, since our hosts didn’t remember that. But not till the end of a ridiculously long comment. You have been warned.]

Our hosts commented on the stories where Dredd himself isn’t very important. I think that was the the big thing that I noticed about this volume — there is a definite increase in the number of Judge Dredd stories that aren’t really about Judge Dredd.

Imagine if 2000 AD had decided to launch a second strip, “Tales of Mega-City One” or something like that — Dredd would make cameo appearances in it to keep the reader interested, but wouldn’t be the protagonist in the same way as he was in “his own” strip. (Like the proposed TV show, if that ever actually happens.) I think quite a lot of the stories in this volume could have fit into that strip instead of Judge Dredd without too much difficulty: Requiem for A Heavyweight, The Weather Man, Bob & Carol & Ted & Ringo, High Society, The House on Runner’s Walk, Portrait of a Politician, and (to an extent) Citizen Snork. Citizen Snork even makes fun of the tendency in its first episode.

This dilutes what I felt signaled the importance of Un-American Graffiti and The Executioner, that in those stories it was a big deal that Wagner & Grant were decentering Dredd and making someone else the protagonist, and that it was saying something significant about Judge Dredd the strip when it did. In this volume, for someone else to be the protagonist is routine: Arnold Stodgman, Clayderman, Granville, Dave… And in Un-American Graffiti and The Executioner, Dredd becomes the antagonist. Here, he sometimes sort of is, but in a lot of the stories above he’s more of a Greek chorus than anything else.

A lot of this is probably an attempt to solve the fact that Judge Dredd the character is a fixed point – he can’t change. Well, it will eventually turn out that he can, but that’s all far in the future at this point, and I think that this version of Judge Dredd (the strip) assumes that (a) the character of Judge Dredd is “finished” – the strip has stopped evolving from its early days and has matured into what it’s going to be and (b) that character, Judge Dredd, was never going to be one that could develop as such, that his unchanging rigidity is the point of him.

For a long time, the trick has been to play this static Dredd off against the variety of stories that you can do in Mega-City One, especially the ones with a self-conscious weirdness about them. Dredd is sort of a straight man a lot of the time. Not that he’s humorless as an individual, but it’s the total seriousness with which he treats the most bizarre occurrences as real and part of the routine of things with which he has to deal. “Nose shot!”

But one can see that there’s something there that pushes you towards the position that Judge Dredd the character isn’t necessarily that important to Judge Dredd the strip. These stories are a riposte to the Cursed Earth Saga, The Day the Law Died, the Judge Child Saga, and the Apocalypse War. They say, “Why on earth do you want to take Judge Dredd out of Mega-City One or make Mega-City One something else? Mega-City One is the most interesting thing about Judge Dredd, and always has been. Make the story *about* Mega-City One! It’s the place where you can tell any story, where anything can happen! The place where an orang-utan can become mayor!”

(And, hmm, Portrait of a Politician is more about stereotyped ideas of America than I initially realized. No accident that its opening turns on American football. It will be interesting to trace this theme when we get to Dredd stories published over the last two decades, as the fact that the US has lower social mobility than Britain comes into public consciousness.)

OK, so there are a lot of stories here where Dredd becomes a secondary character in his own strip. Something of the same agenda creeps in even to some stories where Dredd is still the main character. Especially the Graveyard Shift, with its “slice of life” conceit. Or the way in which Suspect or The Wreckers present the story from someone else’s viewpoint. (Not new – Alone in a Crowd – but striking in the context of all the stories in this volume in which the same shift in perspective is accompanied by reducing Dredd to a secondary character.)

It makes the end of the Dekker mini-arc feel quite wrong, with her saying that she owes everything to the textbook that Dredd wrote. Even at the time I thought it deserved a bit of a cringe. But reading it in the context of this podcast, I think it’s clear that ending is a misjudged throwback to the very early Dredd stories, in which you were being constantly reassured that he was the “top lawman” who was the most important person in Mega-City One.

That’s wrong for where the strip is now, and it’s especially wrong as the conclusion to the Dekker stories, which are the follow-up to the Graveyard Shift. They’re about what Dredd does as routine from his perspective, even though from our perspective the situations that confront them are exceptional. We follow Dredd and Dekker through three stories that could individually be normal Dredd stories with just Dredd in them, and we see Dredd constantly evaluate Dekker based on whether or not she does things in the right way — which is simultaneously, in-story, about following established procedure and, viewed from outside, about following the established literary conventions of how Dredd acts within a Judge Dredd story.

As far as the conclusion goes, it would be fair to say that Wagner & Grant might have written themselves into a corner with the rookie who does everything right, the person who’s going to be Dredd in twenty years time. (She even has an action-story appropriate name. Don’t tell me a child wouldn’t want to read Judge Dekker.) And it was a great idea to flip the original Giant final assessment story like this: one can’t underestimate how important it is, in the context of a “boy’s” comic in the early ‘80s, that Wagner & Grant assign the role of Dredd’s likely successor to a woman. Think of Juliet Bravo — this was a time when “The main character is a woman” was considered a distinguishing feature of a police drama. Cf. how Hershey views Dredd as a senior colleague, but essentially an equal.

(But no, Garth Ennis is going to kill Dekker off. Oh well.)

You extracted a ‘What?!’ from me with your Kim Raymond/Modesty Blaise comment. I recovered somewhat when you said it was Romero, not Holdaway Blaise you were talking about, although I still think it’s a generous comparison.

My tastes concerning Ewins and Gibson are somewhat at odds with yours as well. I’d agree that ‘The Haunting of Sector House 9’ is some of Ewins better comics art. However some of that is because the lack of spatial depth which is characteristic of his pages works for this story. Here it helps create a claustrophobic effect and sense of not being located in space and it does work, but it’s a bit of stopped clock viewing his work overall. Incidentally, is there a story behind the Case Files dubbing Mr E ‘one of the Galaxy’s Greatest Comics most beloved artists’ ? They don’t talk about anyone else in this fashion.

Our takes on Ian Gibson are different as well. However I was wondering why Mr Gibson put ‘Emberton’ to some of these pages, so if you don’t think it was his best, you’re in good company.

‘The Graveyard Shift’ was a big favourite when it came out and still works today. I know it’s not the first place he’s used it, but I want to mention those lovely, shadow-filled head shots Ron Smith so often starts his Dredd stories with..

Finally, at the start of the book, when we’re told that Dredd has made his 300th arrest of the day, do you think it means the 36 hours he’s been up for, or a standard 24 hours? It’s the difference between an average of one arrest every 7.2 minutes or every 4.8 minutes. Of course, given that it’s Dredd, there’s probably some significant clumping of arrests going on.

Graeme mentioned being surprised by the end of the Bingo story, but also how Haunting of Sector House nine was able to play with the expectations of the reader.

I was reminded of something I read about the “Future Shock” comics in 2000ad years ago. If I recall correctly, it said that for those stories your twist couldn’t wait until the last page because readers would be expecting it. You had to put your twist on the first page and then your _second_ twist could be on the last page.

I kind of feel the Bingo story is working that way. The first “twist” is that bingo is illegal and your expectations are that the old people playing it are criminals (a concept potentially hilarious to children reading the comic at the time), the twist that they are actually just addicts/sick and not criminals is surprising, but still allows children to view themselves as better? I dunno. Maybe I’m reaching.

The current issue of Back Issue (115) from Twomorrows has a lengthy history of Judge Dredd. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet so I can’t comment but thought I’d mention it here for those who may be interested

Another insanely long comment. If you don’t want to read it, it boils down to “It took me a remarkably long time to realize that Judge Dredd might actually be about policing.”

Our hosts talked a lot about how Judge Dredd was prescient. An obvious instance of that is the way in which ordinary police in the quite ordinary place in the US in which I live *always* wear body armor nowadays. This was especially obvious this July, when it was hellishly hot and humid. And it can’t help but make a cop that I see in some completely routine situation like at a rear-end collision seem menacing and oppressive to me.

(Although I will say this for Judge Dredd. I wouldn’t be happy if US police had embraced Dredd as a symbol, but he’d be better than the Punisher. At least Dredd thinks of himself as answerable to somebody.)

But this isn’t actually new for me. It’s what I felt when I moved to the US for the first time and had to get used to the sight of armed police. That faded over time, but the body armor has brought it back. Which brings me to my point: I think some of this is actually very much of its time, Britain in the early 1980s, but it speaks to real contemporary fears that as America, so Britain – that Britain was on the same course as America, that applied especially to policing.

Culturally speaking, police dramas are one of the most interesting places where British televisual media worked through questions of postwar national identity, including as regards the US. The policeman or policewoman is a natural symbol of British identity, not least because Britain essentially invented modern policing in the early 19th century. One aspect of this is that pretty much from then on up through quite a bit of the 20th century the British were seen in many other countries as the experts on policing, the innovators who developed new methods to be adopted elsewhere.

This includes in America — American urban police forces as they developed did so in imitation of esp. the Metropolitan Police. But the US rather screwed this up (at least from my perspective), especially because of (a) slavery and its legacy and (b) the weakness of the US civil service ethos and the dominance of the spoils system in how any government-paid job was allocated.

One interesting sign of this is the history of armed police. When US police forces were first set up, there were a number of serious attempts to have them not carry guns on the British model (itself part of the distinct civilian and non-military character of British policing). These failed because police officers insisted on carrying their own privately-owned guns, whether allowed to or not, and pretty soon an unofficially armed police was an officially armed one.

What I’m getting at is that when people talk about the “militarization” of American police as a very recent development, that’s not entirely true – the cultural forces that pull American policing towards a warrior ethos in which it is considered important to be able to respond with lethal force are longstanding, and recent developments should be seen as on a continuum with things that happened back when the first modern US police forces were set up.

Here’s the thing, though: the rise of US film and television drenched British audiences in heroized images of US police forces (and similar figures, like the ”lawmen” in Westerns) engaging in shootouts with bad guys as a form of entertainment. This produces a definite schizophrenia: on the one hand, one can be (rightly) proud of the (mostly) unarmed British police force, on the other hand, it’s less exciting, right? It’s not as fun. (And 2000 AD is definitely about the idea that representations of violence are fun.)

This more violent, exciting American version of police drama haunts postwar British film and TV. The Blue Lamp is a really good example, built around a single gun as a fetishized object of terror that only makes sense against the background of American films in which the gun would be ordinary and one of many such objects – simultaneously aspiring to the excitement of American gun violence and asserting British superiority, especially in the figure of PC Dixon and how he responds when confronted with the gun.

One can trace this combination of envy of and disdain for the US through the subsequent history of British police drama from Dixon’s subsequent TV series up through the early 1980s. Z-Cars, The Sweeney: there’s an intimate relation between being more dynamic and exciting, more cinematic, or more gritty and violent, and being more “like American cops.” At one extreme you have the The Professionals – revisiting its voiceover opening as an adult was absolutely chilling for me:

Anarchy, acts of terror, crimes against the public. To combat it I’ve got special men – experts from the army, the police, from every service – these are The Professionals.

Come on, doesn’t that sound like the same mindset as Judge Dredd to you? And it ran from 1978-1983, pretty much the same era as Dredd has just exited. Particularly striking, against the traditional British emphasis on the civilian character of the police, is the collapsing of police into army and other “services.”

OK, people who are still reading this probably think I’m trading in a very idealized view of British policing. And rightly so – I have been (although I do think British people can justly be proud of a lot of the ideals going back to Peel, if not always the reality).

But the idealized view isn’t just mine – it has historically had a powerful presence in British depictions and popular understandings of the police. And the early 1980s was a time when reality crashed into those ideals in a very painful way, in the form of the 1981 riots and the Scarman Report. This was a crisis for the whole understanding of British police as “policing by consent.”

In ee Rumble in the Jungle in particular. One thing that connects very strongly to this context in this volume is when Hershey and Dredd have a spare moment and do a “59c,” a “crime swoop.” These are an exaggerated version of the actual power of British police in 1981 to stop and search individuals based on no more than “reasonable suspicion.”

Things have to be stamped on “whatever the causes” – this parrots the pervasive and effective right-wing line of attack on left-wing approaches to crime and public order, the one that Blair eventually jiu-jitsued with “Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime.” I can’t help but see the same sympathy (whatever Grant and Wagner’s personal politics) with the Thatcherite position in the bit where the indulgent parents of one of the juves in Rumble in the Jungle say that they’ll have to take away his pocket money. (“If parents just gave children a bit of discipline, like in the good old days…”)

One aspect of this is that the 1981 riots were seen through an American lens, being framed as “race riots.” This is not entirely about America, of course – it goes back to the debates over immigration in the ‘60s. But it was also about framing these events as British equivalents to events like the Watts riots. As America, so now Britain — America as the future.

(“Race riot” is a racist framing of both the American and British events in question, but the point is that it was a racist framing that was current at the time.)

One can see something similar in the introduction of the Manta tank, and Dredd’s response about preferring to be on his bike where he can look people in the eye — which is a slightly clumsy translation into “future!” terms of the whole 20th century debate about putting police in cars that separate them from the population versus having them walk among the public.

But, returning to the 1981 riots, reading this volume, and especially Rumble in the Jungle, against that background does make something uncomfortably visible: Mega-City One is awfully white. One occasionally has non-white characters, but there’s more than a whiff of tokenism about their presence. Most are judges. In fact, I’m not sure that any are not judges. The citizens of Mega-City are essentially an entirely white population.

This is very awkward in a depiction of policing at a time when real life had made it very hard to ignore that policing had, at a minimum, a serious problem with racism, not just in America but also in Britain.

A couple of other scattered thoughts:-

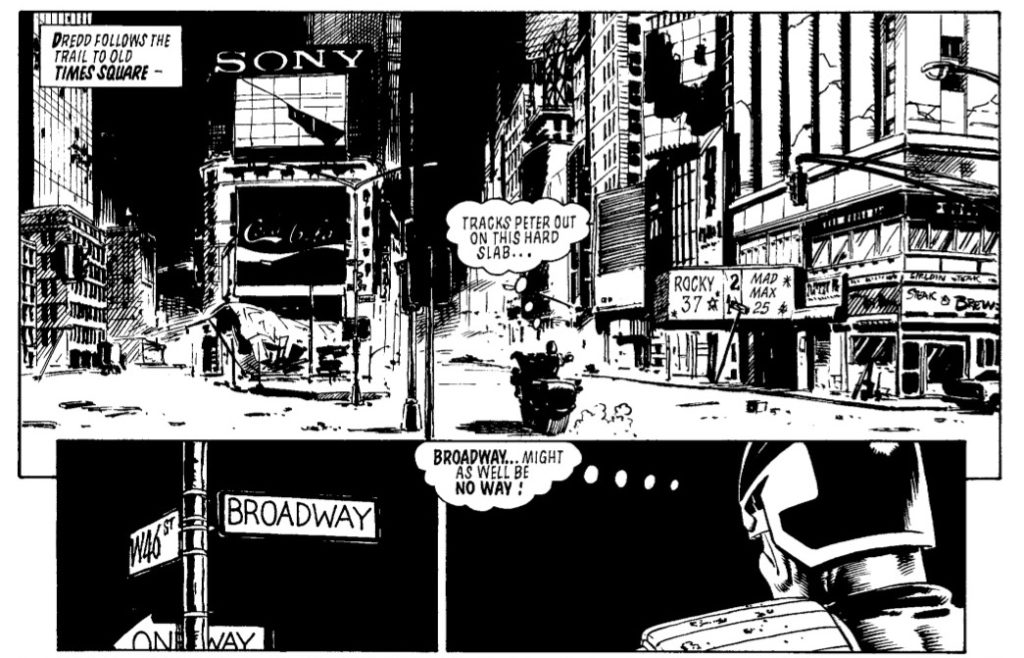

– I’ve always been surprised that Judge Dredd didn’t do more with the Undercity. That whole idea of a separate, buried world that is recognizable as the past/our present, in this case as New York. It seems to me that you could do a lot with that idea of a buried past that has been overwritten by Mega-City One.

But it didn’t come up that often, at least not in those parts of Dredd that I know, and about the only time where I think it came close to realizing its potential was in whatever the hell was going on in Wagner’s subconscious when he came up with Fergee.

In this story, I think it’s really just an excuse to have Central Park as an appropriate visual background for werewolves.

– For all that I’ve been trying to emphasize how attuned this is (but ambiguously so!) to the politics of the time, the “Lib-Lab-Flab” bit was horribly dated when this came out, and really weird in the era of the SDLP-Liberal alliance. How many people in the target audience could remember the Callaghan government at this point? I’m pretty damn sure that I would not have had a clue what this was referring to at the time.

This might be in my top 3 volumes of Judge Dredd thus far, and for me it passed the litmus test of would I give it to someone for the thier introduction to Dredd with a resounding yes. As usual, great discussion from our hosts, and great comments from Voord 99. There were, however, a few things that stood out/didn’t sit well with me, and I don’t think they were touched upon in the show.

1. When Dredd goes into the Undercity, he’s set upon by some vagabonds. He quickly scares them off, but thinks, “Pathetic scum. People who’ve sunk as low as the whole they live in. Got no time to help ’em.” Then the next panel, a close-up of Dredd’s face in profile: “Even if I did, I wouldn’t!” That just floored me, and especially when Dredd shows so much relative compassion throughout the volument (e.g., lamenting all the deaths in the block war, letting the bingo players go, allowing the dinosaurs to escape, and always trying to bring in futsies without hurting them).

2. In “High Society,” the story has zero problem equating poor people with criminals, even though we’ve seen in Dredd that criminals come from all sorts of socioeconomic backgrounds. I supposed it could be rationalized that with heavy unemployment and literally nothing to occupy them, poor people turn to crime in Mega-City One and that’s just how it is. But Wagner and Grant don’t live in Mega-City One, so it came off as rather hateful of the poor.

3. The way the overweight citizens are treated by the judges is just awful. It’s odd that senior citizens have an addition to bingo that absolves them of any criminality, but it’s obvious the overweight citizens are not only suffering from addiction themselves, they’re also being exploited through that very addiction.

Finally, regarding the pacing of British comics vis a vis their American counterparts: I feel like you two might be on to something there. Wagner and Grant’s DC work has a lot of the hallmarks of the high concept stuff they were doing in 2000 A.D. (from introducing the Ventriloquist in Batman to those first run of Lobos stories), but with the monthly pacing and higher page counts per installment, I feel like they rarely reach the lofty heights seen here, height they seem to reach with apparent ease.

Re: waiting for Dekker.

Have you gotten to Judgement Day yet? Bad luck for Dekker-watchers!