Previously on Baxter Building: The John Byrne era is over, with the writer/artist who, let’s be honest, left his stamp on the series more than anyone else aside from Lee and Kirby, departing after five years mid-storyline. In his place, we got a couple of fill-in issues leading up to what should be a big deal: two big anniversary issues within six months of each other. Will they live up to the occasion? Spoilers: No.

0:00:00-0:05:34: A punchy opening — for some reason, Jeff and I talked for an hour and a half before recording, don’t ask me why — leads us into introducing the issues we’re covering this episode: Fantastic Four #296-303. Or, as Jeff puts it, the issues in which “a whole bunch of people [are] trying to wrestle with where Byrne was steering the work, and trying to make it work, and frankly just not being able to fucking do so.” On the plus side: these issues are also kind of terrible. Wait, did I say plus side…?

0:05:35-0:30:57: We open with the 25th anniversary issue of the series, Fantastic Four #296, which is handled with all the sensitivity and appropriateness it deserves — which is to say, almost none. Jeff and I talk about Jim Shooter’s plotting skills, whether or not Stan Lee is Reed Richards (and, if so, who does that make Sue?), John Byrne’s original plot for the issue before he was fired, and the perils of jam issues when so many artists are involved in general. All this, plus the secret origins of Frank Miller’s Sin City art style, too!

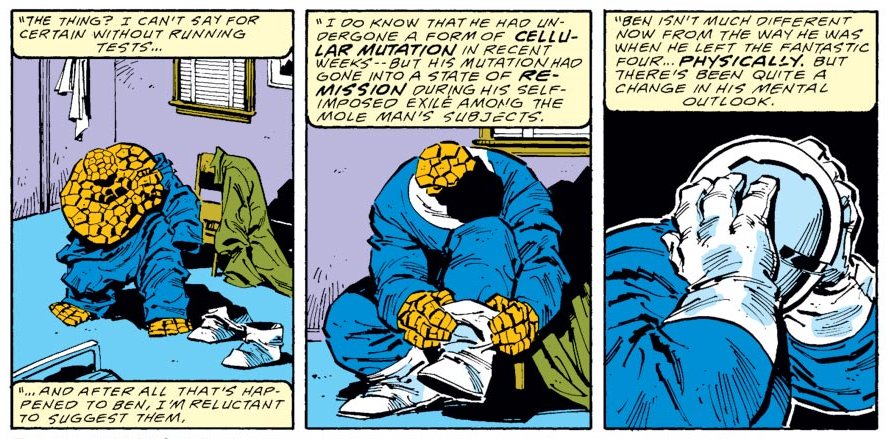

0:30:58-0:41:58: FF #297 introduces a short-lived new regular creative team of Roger Stern, John Buscema and Sal Buscema, and somehow, the combination is far less than the sum of its parts. Still, we do get to talk about the production schedule of the book, the bad advice of Reed Richards, the subtext of the issue’s villains — well, as Jeff reads it, anyway — and Roger Stern’s abandoned plan for Benjamin J. Grimm.

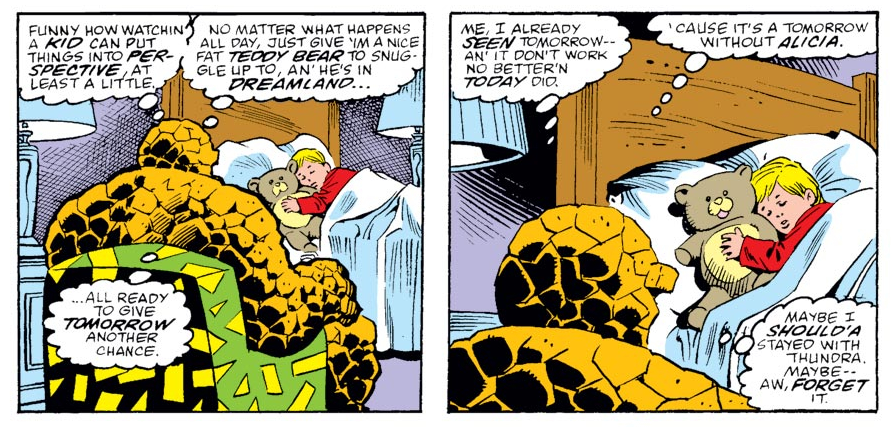

0:41:59-0:47:37: In the immortal words of Mr. Jefferson P. Lester, Fantastic Four #298 is “also dull as fuck.” He’s not wrong; the conclusion of the two-parter begun in the previous issue, the highlight is probably the sight of a villain trying to choke himself to death. (See above.) We end up talking about the fact that the series can’t allow Ben Grimm to evolve emotionally any more, and the possible reasons for that beyond a misguided attempt to make the book “grittier,” because the late 1980s weren’t a kind time for those unimpressed by anti-heroes.

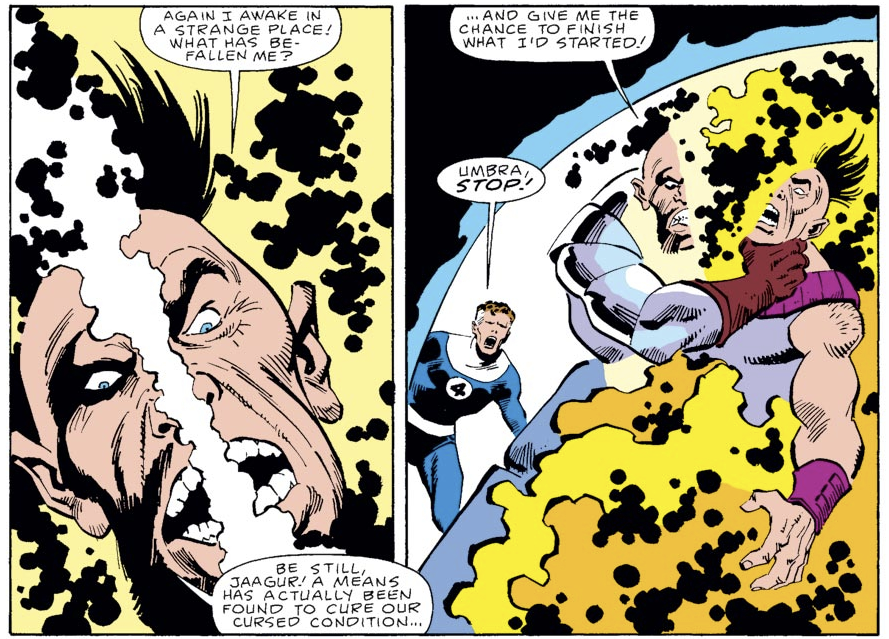

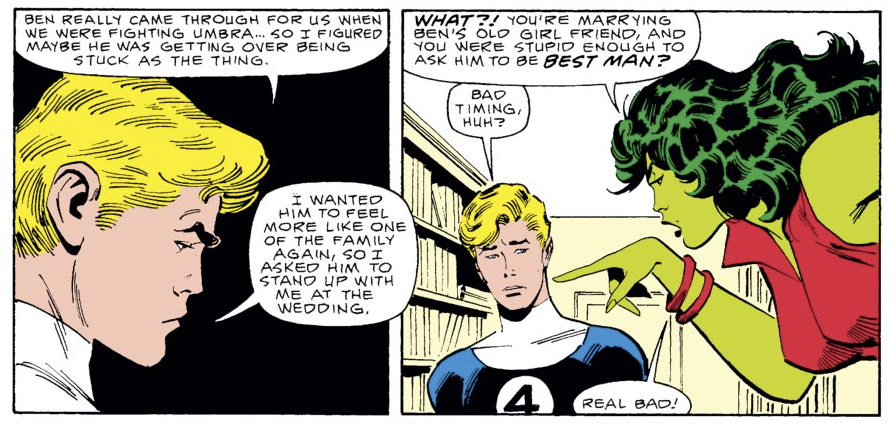

0:47:38-0:54:51: You know who the hero of FF #299 is? She-Hulk. You know who’s about to entirely disappear from the series without explanation? I’ll give you a clue: She’s seven-feet tell and bright green. As a swan song, this is kind of a good issue and offers what could be closure for Grumpy Ben Grimm™ if he was allowed to have closure. Meanwhile, the rest of the Fantastic Four continue to be the worst, She-Hulk and Wyatt Wingfoot explain the downside of the First Family’s closeness and you will really wish Jeff was writing the ongoing adventures of 1986’s Johnny Storm.

0:54:52-1:01:39: There are a few things that Jeff and I really enjoy about Fantastic Four #300 — Doctor Doom’s response to Johnny and Alicia’s wedding, for one thing, as well as the Yancy Street Gang’s method of therapy and the fact that even the Puppet Master isn’t a complete dick, not to mention the single greatest Franklin Richards drawing ever — but for those looking forward to the kind of anniversary bonanza that celebrates the history of the comic and makes you feel excited for what lies ahead… yeah. Maybe not. Still, at least John Buscema has the chance to draw random nobodies as wedding guests.

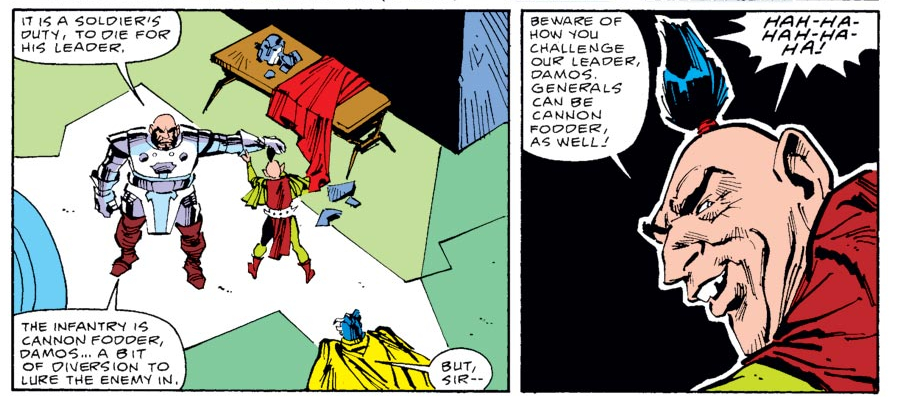

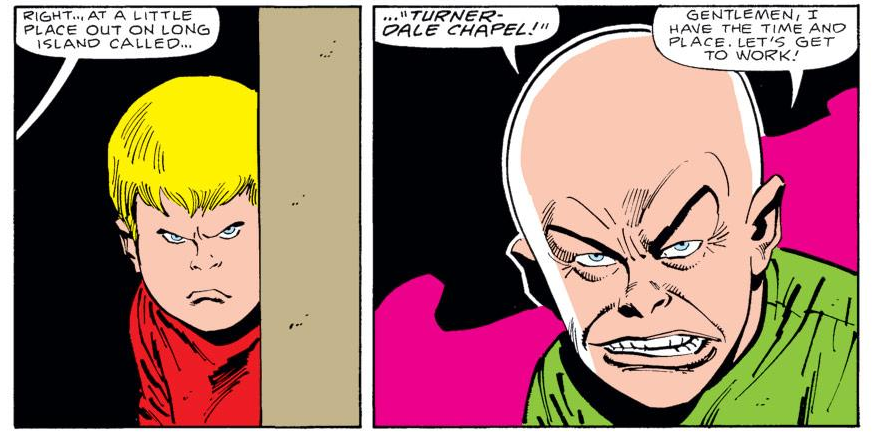

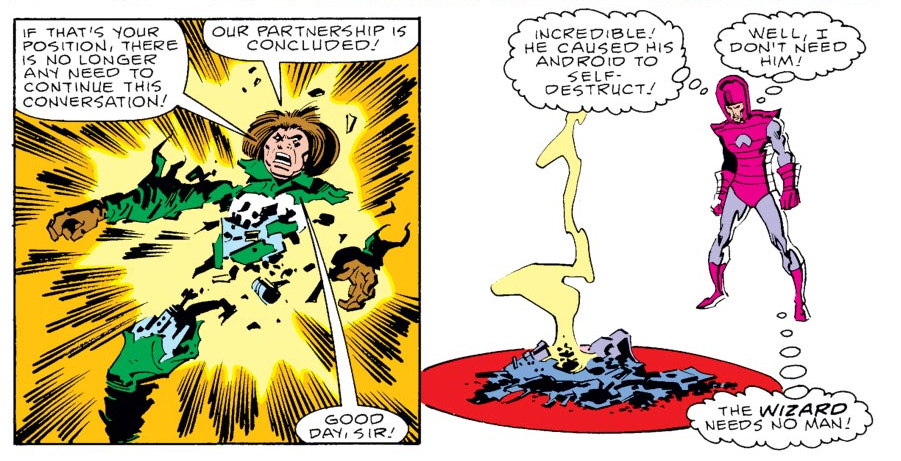

1:01:40-1:09:27: Say what you like about FF #301, but you can’t deny that the Mad Thinker knows how to exit a conversation. (He’s also not a kid killer, so there’s that.) After Jeff comes up with the best description of Tom DeFalco and Paul Ryan’s upcoming Fantastic Four run — “Dad Squared” — we talk about the drawbacks of the Wizard’s plan and discuss even more evidence that Johnny Storm might actually be even more “the worst” than Reed Richards. What in the world is happening?!?

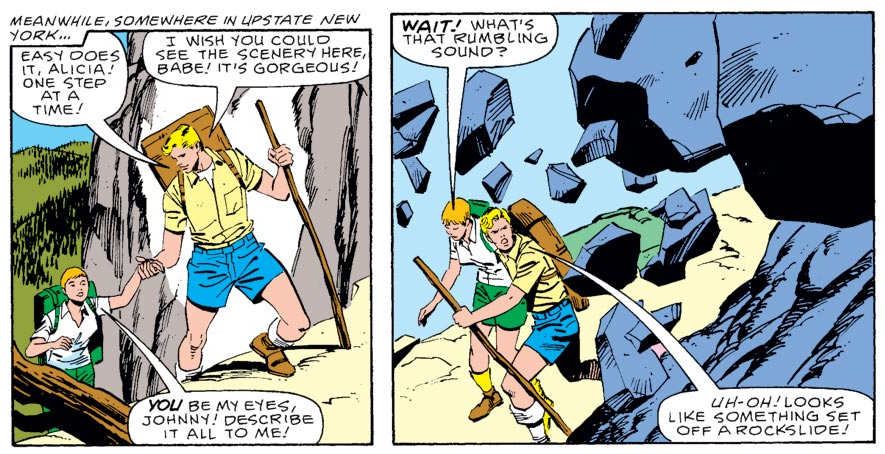

1:09:28-1:31:15: The final issue of Roger Stern’s run — although Fantastic Four #302, like the last issue, is only plotted by Stern and scripted by Tom DeFalco — brings discussion of Johnny Storm’s new catchphrase and name, as well as the dumbest plot to avoid nuclear apocalypse ever, and Reed and Franklin’s awkward father/son talk. Also, Jeff gets into a fugue state about Alicia’s desires and I make a pun so bad that it temporarily stops Mr. Lester in his tracks. Success!

1:31:16-1:41:00: Limping towards the finish line, FF #303 brings Roy Thomas back, but it’s Thundra’s return that gets Jeff Lester excited. The same can’t be said about the Thing, who’s continuing to dominate the series just months after returning, with Thomas offering up even more potential closure for the character that manages to contradict everything that the series had been claiming to this point. But this is perhaps better, so… yay… ish…?

1:41:01-end: Exhausted by bad comics, we talk about whether or not the high number of shitty Fantastic Four comics means that the Fantastic Four is a shitty concept, and end up in a food analogy that just made me hungry while editing the episode. Are there three sides to a successful FF story, and will we remember to use this metric on future runs? The answer to one of those questions is no. As everything gets wrapped up, we lay out the next batch of issues we’re going to cover — FF #s 304-313 — and remind you to visit the Twitter, Tumblr and Patreon, as usual. As with every episode, thank you for listening and thank you for reading through these show notes. Next time, I promise, will be more fun. It’s Englehart time!

For those who want the direct download link: http://theworkingdraft.com/media/podcasts2/BaxterBuildingEp33.mp3

Interesting reflections at the end about the challenging nature of the Fantastic Four as a concept when it comes to producing good stories. Even if it’s a little sad that you spend all these months and read two-and-a-half decades worth of comics, and then it strikes you: “Most of these aren’t any good, are they?”

But I think it’s true. The Fantastic Four is cursed by the strength and importance of the original Lee/Kirby run. So not only does it seem like it should be good, when it’s only mediocre (which is what it often is) it seems that much worse in contrast to our idealized expectation of its “real” goodness.

Some thoughts about this (at what will probably be ridiculous length)…

It occurred to me the other day that the Fantastic Four had a lot in common when it started out with Doctor Who. Very close in time, obviously, and with a similar science-fiction remit (although mercifully an American superhero comic was never going to have the po-faced Reithian educational self-importance of a BBC show in the early 60’s). Both enjoy rapid success and become cultural phenomena – DW more than FF, in part because of the greater reach and prestige of its medium, in part because Britain is just smaller than America, but both.

And both are built around a similar reliable four-part ensemble structure: male lead (Reed/Ian), female lead (Sue/Barbara), kid (Johnny/Susan), and off-putting anti-hero (Ben/The Doctor). There are some obvious differences – Doctor Who is far less sexist in its version – but there’s a basic similarity in how the character dynamics function as a storytelling engine.

So why has Doctor Who proved so capable of reinventing itself where the Fantastic Four seems so moribund? Well, that’s really obvious – Doctor Who is nothing like that original version, and hasn’t been since the first few stories. It developed rapidly towards something different and more flexible.

Meanwhile, the Fantastic Four remain pretty much as they were in 1962, The main change, Ben losing his sharp edges, happened, as our hosts note, very rapidly, and over time Sue’s personality has come to, well, exist. Johnny has repeatedly been matured and then reset to someone who behaves like a teenager (although ostensibly in what, his late twenties?). But, basically, it’s that four-part ensemble, with the same male and female leads, a kid, and the quirky, “different,” fourth guy.

(I’m surprised that no-one has “permanently” depowered Reed and confined him to his lab as tech support/scientific advice in a sort of Oracle role, while Sue becomes leader of the team in the field. It seems an obvious way to rewrite the way in which the characters relate to one another in stories, and one more likely to feel “right” to nostalgic superhero fans than replacing members of the FF, which has been tried a ridiculous number of times.)

So, if we take ingredient 1 of the FF, with our hosts, as being soap opera, there’s a problem here, in that the basic character relationships are too static. Whatever you try, it’s been done, and done better. Actual soaps churn characters regularly, as do successful superhero equivalents like the X-Men.

OK, but that’s Marvel superheroes’ famous illusion of change for you, right? What makes the FF different from other superhero comics here? I think that, on the one hand, it’s too small: the number of relationships between the characters is limited. On the other hand, it’s too large, because to serve all the characters you limit the amount of storytelling you can devote to their relationships outside the group. On the first count, I’d contrast the sprawling, variable, casts of the Avengers and the X-Men. On the second count, I’d again contrast Doctor Who, which by boiling things down to the Doctor at the center, plus a small number of companions (eventually normally one female companion) as (in the old series) distinctly secondary characters shifted the focus away from the internal dynamics of the regular characters to how they interacted with the people that they met. The Fantastic Four fall uncomfortably between two stools, and there is not much to be done about this, because it’s central to the idea of the FF as a “family.”

Then there’s ingredient 2. I think our hosts are correct that Kirby *awe* is a critical element to the FF. It’s about juxtaposing those small family relationships (before they became stale) with the cosmic and the really, really big.

And here, I think the FF’s great nemesis was the psychedelic era. There’s something irreducibly early-60s about the FF, astronaut-heroes led by a wise scientist authority figure. But more than that, they worked in the early Marvel universe, when Kirby could fill the concept with a stream of new concepts that were still in that basic classic science-fiction aesthetic.

But by the ’70s, that’s horribly dated. The Marvel universe has been filled up by Starlin and co. with personified abstract concepts of an “Am I blowing your *mind*? Can you grok it?” character: Eternity, Death, the In-Betweener, etc. The Fantastic Four’s aesthetic doesn’t really go there: you can’t imagine Reed dealing with things like that, because it’s the equivalent of imagining him doing acid and dropping out. Kirby’s own ’70s work is maybe the biggest illustration of this, because he was, as usual, attuned to the need to do something new to respond to changes in the cultural context and his solution to how to make the same themes work in the new world was to ditch the astronauts-and-labs in favor of things that were on a larger scale and/or more rooted in history and myth.

So the Fantastic Four seems small as a comic from the ’70s on, and I would argue that it can’t afford to seem small. It’s sort of worked at various points since then. Under Byrne, partly because it was the ’80s, and pop culture was in backlash against the psychedelic stuff that is so inimical to the FF, partly because of Byrne’s rock-solid traditionalist faith that, goshdarnit, the FF are at the center of the Marvel universe and Reed is at the center of the FF. Under Waid/Wieringo, because Waid is interested in portraying these as four likeable and well-adjusted people in *situations* that are interesting, which should be bland, but in the context of the FF’s history feels quite refreshing. And so on.

But at the end of the day, I think that the FF may be a concept that worked so well at one point because it was so responsive to its cultural moment, and by that token didn’t adapt well to later times.

There is one element of the classic Lee/Kirby model with which I think more could be done: superheroes as celebrities, since celebrity culture is something in which we still have a lot in common with our distant forebears in the 1960s. I am surprised, but relieved, that no-one has done the Fantastic Four as the Kardashians or whatever. Probably it would seem blasphemous to superhero comics fans’ sense of nostalgia (thank God). But I think that more could be done there.

Voord: I thought this was a brilliant set of a points that far outstrips our original comments. Really quite nice!

I only read the first issue or two before giving up, but didn’t Millar and Hitch’s run try some aspect of that “superheroes as celebrities” approach? Johnny dating a celebrity, Ben pulling attractive women who were only into him for his fame, etc., etc.?

Also, has anyone ever done the superheroes-as-celebrities idea right? I know Booster Gold and some other books built around the concept lasted a while and were popular, but I never felt they actually did the concept any justice. Most of them tended to show someone draped in swag going, “yeehaw, I love being a celebrity!” But that always seemed to run counter to the way a lot of celebs downplay their entitlement (especially to themselves).

So, although it always seems like great groundwork for an idea, I feel like it never really works. Is that just me?

Surely superheroes as celebrities is the core concept of much of Morrison and Yeowell’s Zenith? Certainly the first, second and fourth “phases” of the series play with that idea quite a bunch, with the second also playing with the idea of “celebrity as supervillain through sheer force of will” in a way that’s as much Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs as it is Lex Luthor. Whether or not it’s doing it right is another question, of course…

Oh right, Zenith! Jeez, I just realize I never made it past the first phase–I need to correct that.

Milligan and Allred’s X-Force was pretty great.

Ooo, yeah. I think that is a pretty good example of a book that did it right–though as I recall, the celeb bits were extra satirical touches on an already semi-satirical book. Which is fine, but I guess I was thinking about it as a concept handled “seriously.”

Jay Faerber had that series at Image Noble Causes about a whole family of famous superheroes. I can’t say whether it’s what you’re looking for, I only saw it when it crossed over with his other superhero book at Image, Dynamo 5.

Itemizing the various approaches to superheroes as celebrities represented by all this:

1) Superhero celebrities as “This is what a person with superpowers would do in the real world” (Zenith, with an added dose there of “This is a way to ground superheroes in contemporary, i.e. late ’80s, Britain.”)

2) Superhero celebrities as satire of celebrity culture (X-Statix).

3) Superhero celebrities as satire of superheroes (Noble Causes – I think. I don’t know it well. It’s something that I looked at in the store when it came out, thought it looked interesting but not interesting enough to read right then, and put it on my mental list of “maybe someday if I have time/money.”)

4) Superhero celebrities as a way of making a tired concept seem fresher by introducing notes of “Ooh, that’s a little bit daring (but only a little)” into something that the reader is expecting to be handled more reverently (Millar/Hitch FF – haven’t read much of it, but that’s my impression.)

Of the above, I think (1) the Zenith approach (minus the obsession with British identity, but maybe with some replacement interest) is probably closest to what Mr. Lester wants?

The satirical approaches can be ruled out, I think, and the patented Millar carefully-calibrated* provocation isn’t really about celebrities so much as the reader’s expectations of superhero comics.

Note that Morrison sets you up to dislike Zenith as Stock, Aitken, and Waterman product, but actually characterizes him pretty sympathetically. This suggests to me that maybe the closest thing to what Mr. Lester is looking for is Gillen/McKelvie’s The Wicked and the Divine. Which is really *this* close to being a superhero comic, and has plenty of sympathy for most of its cast of celebrity gods.

So the Fantastic Four as a science-fiction The Wicked and the Divine?

Fun discussion! The only part I would quibble with is the psychedelic era being the downfall of the FF. I mean, yes, that storytelling style doesn’t mesh well with the FF (even if the visuals should be a perfect match)–it’s hard to imagine Reed having an encounter with one of those Living Personifications of Death and Shit or committing himself to the moral self-exploration of Starlin’s tortured messiahs. The FF go into space to discover other worlds, not themselves, and to some extent that cut against the prevailing spirit of the times.

But I don’t think that’s what’s hampered the FF since Kirby’s departure (with the odd and welcome exception here and there). They’re explorers in a shared universe that, by the 1970s, had already been pretty well explored. They can’t discover a new anti-matter universe anymore–Marvel’s already got one. Same with microverses, star-spanning alien empires, lost cities of inhumans and blue areas of the Moon. The great exploration phase of the Marvel Universe was over and seventies Marvel shifted over to consolidating and sorting continuity, which should be anathema to that explorers spirit. Not to mention most creators don’t have the restless creativity that Kirby did, and realize they have no financial or legal incentive to give their best ideas to Marvel even if they did. Sometimes creators will try to supply the missing element by sending the FF on an odyssey through time or whatever, but it’s hard to see them getting around this problem when the best niches have already been filled.

Yes, I think that’s true too – the FF worked best when one – or, rather, Kirby – could use them as a vehicle for new ideas.

But I don’t see that as a contradiction – by the ‘70s, the space for new ideas had moved to the psychedelic stuff, and the FF couldn’t go there easily, even if someone had tried.

In contrast, for instance, one can imagine an alternative universe in which someone decided to do that with Green Lantern instead of have him drive around America with Green Arrow learning about social issues, and it would have, I think, been something that the character could do. (“Have you ever considered, Hal Jordan of Earth, what it MEANS that your ring is limited only by your mind?”)

“The FF as super-hero celebrities” would probably start with a formula like:

Reed doesn’t care about celebrity, he wants to focus on science. Celebrity is a nuisance.

Sue accepts the FF’s fame as a means to promote charities and do some good for the world. She is mindful of the team’s image and often acts as its spokesperson.

Johnny embraces being a celebrity, often to his detriment. As a result of living the stereotypical young celebrity life, he’s become tabloid fodder.

Ben doesn’t want to endure the spotlight due to his freakish appearance, but he created his “idol o’ millions, ever login’ blue-eyed Thing” persona in order to make himself palatable to the public.

The people of the Marvel Univrrse are fickle, and will either love or hate the FF in an instant. Several super-villains see fighting the FF as a way to make a name for themselves, as their fights get the most publicity. Dr. Doom is exactly the same as he is in the 616 universe.

The FF members would trade roles depending on the story (e.g. Reed gets into a scandal inadvertently, Johnny has to be team spokesman and not mess up, etc.) and we’d see them have to deal with all kinds of media (from Entertainment Tonight to the Bugle to Fox News to HuffPost). How can they keep up with the 24 hr news cycle and social media? How can they explain Galactus or the Skrulls without causing a panic? What happens when the public finds out the Sub-Mariner’s invasion of New York wouldn’t have happened if Johnny hadn’t unlocked his memories?

I probably would have liked Ultimate FF if the comic had been about a family of celebrity super-heroes.

Mark Waid at the start of his run has Mr Fantastic reveal he set out to make the FF celebrities so they wouldn’t be monsters.

When you said that the podcast was going to be “grim and gritty,” and also deal with contemporary politics, my mind immediately flashed up an image of Donald Trump done up as an early-9os supercharacter: ponytail, pouches, unnecessary straps, one of those Gambit-style head things that doesn’t cover the face or the top of the head, but covers everything else.

Thank you for that mental image.

Oops. Put that in the wrong comment section somehow. That was for the most recent podcast.