Previously on Drokk!: A decade into the comic book career of Mega-City One’s finest lawman, and it’s becoming increasingly clear that the writing partnership of John Wagner and Alan Grant is almost without peer — and also that Wagner and Grant are leaning more and more into the idea that the strip is named after someone standing up for a fascistic regime.

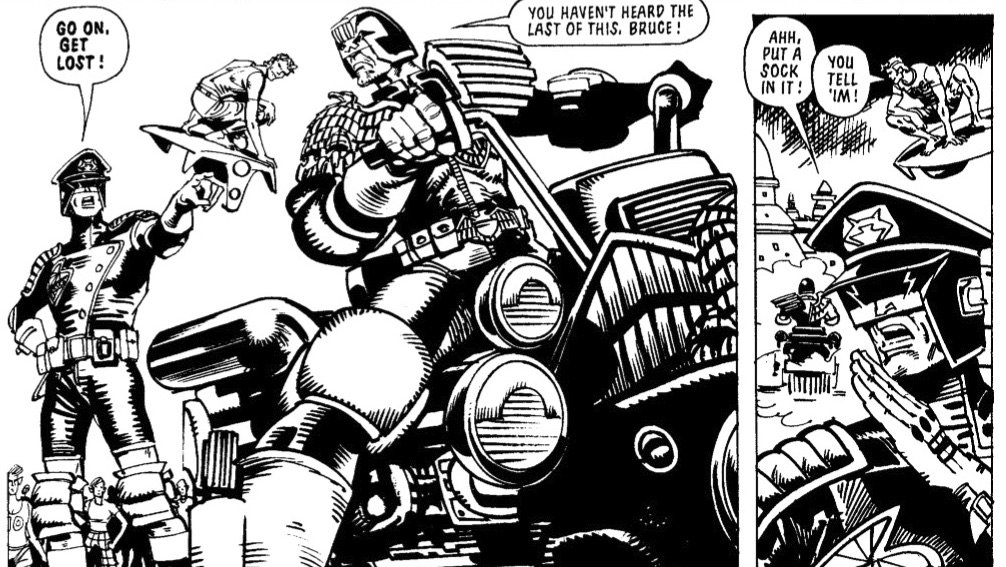

0:00:00-0:03:11: As we introduce what we’re covering in this episode, let’s embrace the fact that I get the volume number wrong; it’s actually Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Volume 11, not Volume 12. I knew this would happen when once the episode numbers and the volume numbers got out of sync! Anyway, it’s material from 2000 AD progs 523-570, from 1987 and 1988, with art by a whole host of people, including Cliff Robinson, Steve Dillon, Brett Ewins, Brendan McCarthy, Will Simpson and Jim Baikie.

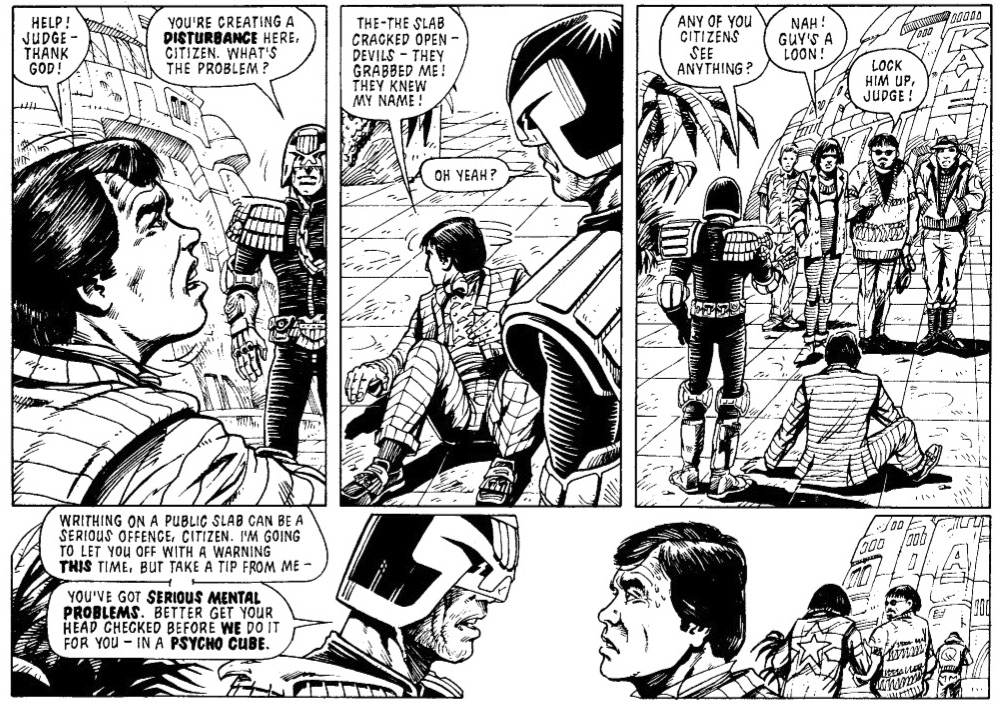

0:03:12-0:38:59: We immediately dive into things, with Jeff asking what my favorite story in the collection is outside of the two obvious choices, “Revolution” and “Oz.” I talk about my choices, which leads into my grand operating theory for the book, which is that it’s a collection where the Judges are waging a psychological war on the citizens, and are focusing on the optics and propaganda of maintaining power more than anything else. This, in turn, becomes a conversation about whether or not Wagner and Grant were planning future stories in advance, with evidence for and against the idea, and if this means that Dredd really is beginning to evolve in this volume or if I’m imagining it given what follows next. We also get into the difference between Dredd as a strip and the U.S. monthly comic, in the sense of the number of recurring concepts and characters as well as the importance of (admittedly dark) comedy to Dredd as a character and a strip, as well as Jeff’s choice for favorite story, the Judge-gone-wrong “Raggedy Man,” which features perhaps the greatest ending of a Dredd story in some time. All this and the scariness of Judges gone wrong, the importance of brevity, and the secret origin(s) of Garth Ennis. No, really.

0:39:00-0:46:25: Jeff answers the traditional episode-end question about whether or not the volume would serve as a good introduction to new readers early with an uncertainty, and we talk about the power these stories gain from knowing what came before, as well as Wagner and Grant’s ability to write a good stand-alone adventure story.

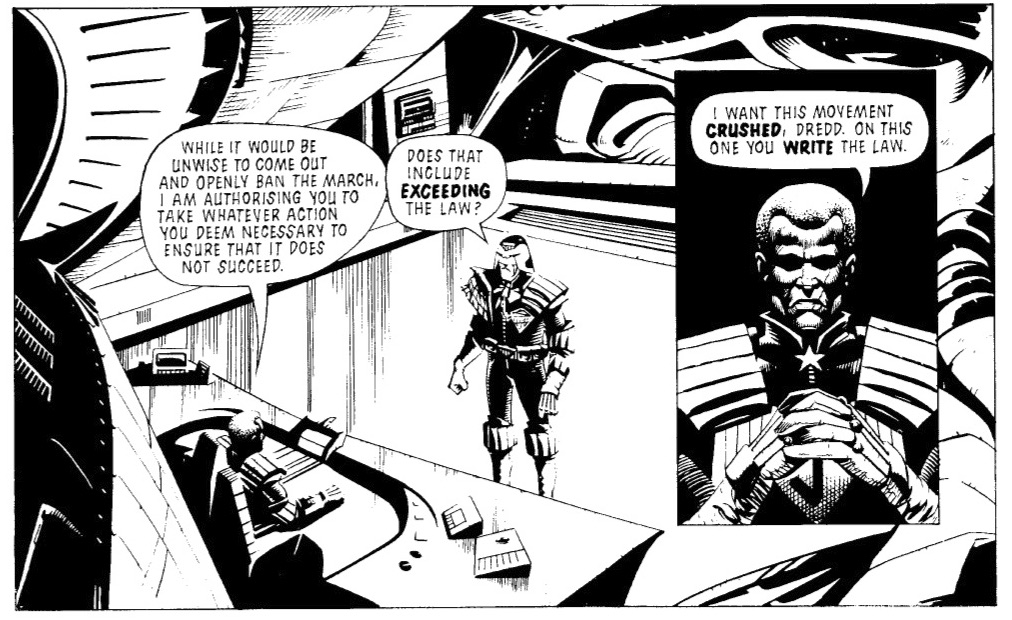

0:46:26-1:05:23: We turn to “Revolution,” one of the two highlights of the volume. It’s a sequel to “Letter From A Democrat” from Volume 9, and it’s the bluntest story yet in terms of portraying the Judges as the villains of the world pretty unambiguously. We talk about how powerful it is, how bold it is, how depressingly prescient it is, and what it means for the character and the strip as a whole. Spoilers: Jeff and I are very much fans of this story in particular; “it is a masterful achievement” might be a phrase uttered.

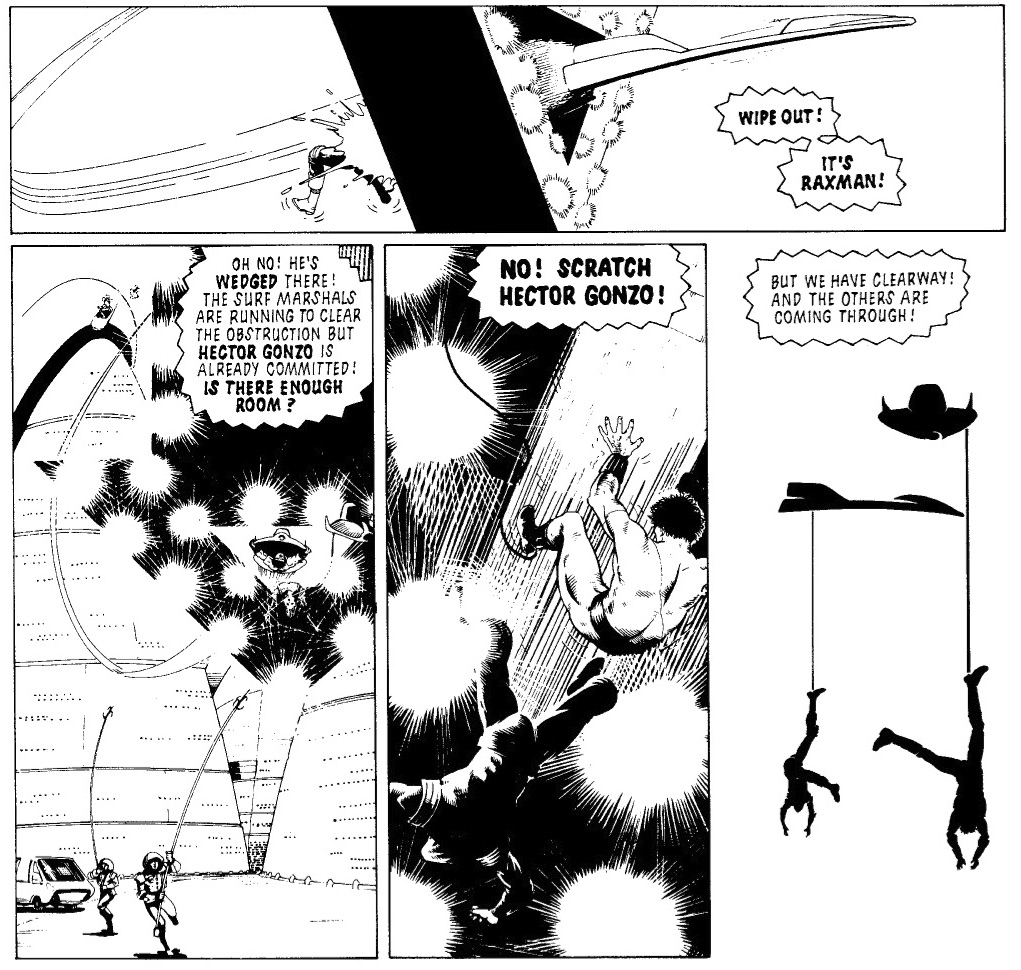

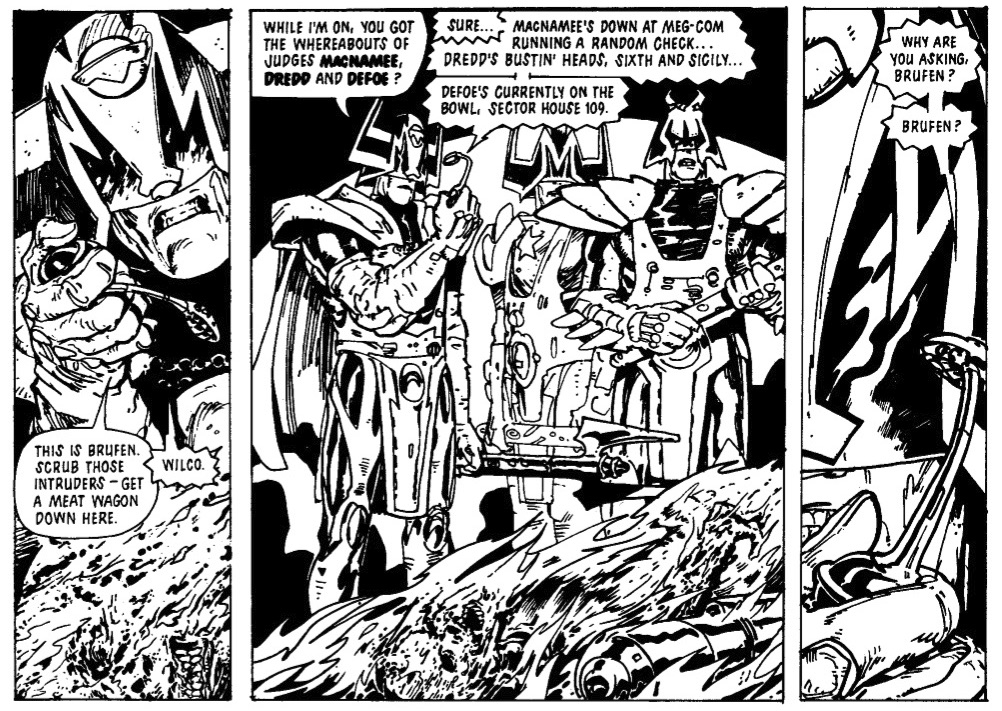

1:05:24-1:56:32: And so, to the biggest story in the volume, and its crowning achievement: “Oz,” the first mega-epic in some time, and perhaps one of the best in the series’ four-decade-plus run. Across a meandering 50 minutes, we talk about everything from the influence of earlier mega-epics to just how unimportant Judge Dredd actually is to the story, even though this might be an exceptionally important story in Dredd’s overall development as a character — although that might depend on whether you buy into my reading of the climax more than Jeff does. Also discussed: am I reading too much into the climax of this story and if I am, what is actually happening in it? The differing worldviews of Wagner and Grant and why this story broke up their writing partnership, how “Oz” ties in with, and acts as a culmination of, the larger themes in this volume, Dredd’s love of nuking countries, how dark is too dark for a Dredd story, and the joys of Dredd as a sports comic and Wagner and Grant as sports writers. We cover a lot, but you’d expect that for almost an hour’s worth of conversation.

1:56:33-2:15:34: We drift towards the end in the old traditional way: Me waxing nostalgic about reading Dredd as a kid and not really understanding things, which leads onto a larger discussion about not getting things in comics as kids, as well as a brief mention of various pop culture references to be found in this volume and the evolution in the way Wagner and Grant approach such references in Dredd as a whole. I ask Jeff if he fancies following Chopper into his own series, and Jeff shares his ideas of what becomes of Chopper without having read those stories, and Mr. Lester also coins the new catchphrase of the podcast when he declares whether things are — wait for it — “Drokk or Dross!” Say it with us!

2:15:35-end: Things get wrapped up as we remind everyone about the Twitter, Tumblr, Instragram and Patreon, and let you all know that we’ll be back doing the Drokk! this time next month. (I also apologize for the technical errors that we’ve had lately, but if this post is live, then those are… hopefully behind us…? My fingers are crossed…)

A few things.

1. I’m glad that you’re doing this podcast because I’m really enjoying reading along and I never would have read this much Dredd without it. I’d read a reasonable amount of Dredd before, but never in such a sustained and comprehensive manner and I think it’s really one of the highlights of my comic reading every month.

2. I realllly wish that this Case File had been in colour. Seeing the pages in greytones was disappointing. I think the next volume starts printing them in colour?

3. You mention this in the episode, but I think it’s wild that chapter 11 of Chopper is (as far as I noticed) the first episode of Dredd with no appearance of Dredd or even Mega City One. (There was an episode of Kenny Who? that just featured a drawing of Dredd on a TV, but it was still in Mega City One.) I’m curious as to what the letters pages in 2000ad were saying at this point. Were readers upset that Dredd wasn’t really in the Chopper story? Or did people appreciate it for what it is? (I thought it was great!)

4. Part of me wondered if the Judda appearance was supposed to happen before Chopper escaped. The way that Dredd allowed Chopper to escape seemed way too…easy? I wonder if the original intention was that it was staged, which makes sense if Dredd had a reason to go to Australia… (Though, they didn’t realize that Judda were in Australia until after Dredd went there I think?) Though maybe Wagner and Grant just took the easiest way to let Chopper escape.

5. I found this website featuring “A Short History of Female Judges in Judge Dredd” that tracks every appearance by a female judge that you might find interesting: https://judgeanon.tumblr.com/FemaleJudges I hadn’t realized that Bolland had drawn the first appearances of Anderson, Hershey, and McGruder.

Great episode, in which our hosts made loads of really interesting observations. Personally, I enjoyed reading Oz at the time, but it didn’t get to me quite like Necropolis did, and I can’t wait for Jeff Lester to encounter that.

Scattered thoughts:-

-Our hosts raised the question of what to call the stereotypes in the Alabamy Blimps. If this were an American production, one could straightforwardly call them classist. It’s just that they’re not *British* classist stereotypes.

I think this illustrates rather well that when Dredd is about America, it’s about American media depictions — in this case horribly classist ones — of America as consumed in Britain. It reflects the degree to which American TV and film have been a pervasive presence in Britain for decades, producing at least the illusion of familiarity that goes beyond what one would normally have with a foreign country.

All this is as much about British anxieties about the British relationship with America as it is about America itself. Which makes it interesting that this story is the first time that we’ve had a depiction of Britishness within Judge Dredd that has some actual content to it: Judge Gomery was a completely blank character, and Kenny Who? was presented as a sort of everyman, a default norm in contrast with the weird US environment.

It’s striking that what we get for our first real depiction of Britishness in the entire history of this British comic strip is another class stereotype, but in the other direction: the upper-class twit and his deferential servant. Britishness is effete, class-ridden, oppressive, arrogant, and stupid, apparently. Our hosts pointed to Wodehouse: Brit-Cit would be, judging from this version of its ambassador, a sort of dystopian exaggeration of our imagined versions of Edwardian England [sic]. He’s not obviously from a *future* Britain at all (aside from the joke of giving him a mohawk and making his servant a skinhead, suggesting a future in which those markers mean the inverse of what they did at the time).

So I think there’s something quite interesting in the confrontation of the upper-class twit with specifically *classist* American stereotypes (recycled from a British perspective). W&G seem to delight in presenting the “lower-class’ Florida characters as superior to this person: they might be crude, predatory, and (as it happens) cannibals, but they’re not annoying, stupid, ineffectual, and full of themselves in the way that the ambassador is.

I have the sense that Cal vs. Fergie would be worth revisiting in this context.

Note also that a more positive stiff-upper-lip version of essentially the same stereotype appears in the British character in Oz.

-This is not to say that the Alabamy Blimps story is particularly good, because it’s not.

Although I do like when the other judge says, “Nice work so far, Joe,” plus Dredd’s exasperated reaction. I always like it when his colleagues don’t think of Dredd as the star of the comic.

I don’t know if I’ve gone through this here before, but I think the Britain as a culture expresses a class-based contempt for the US. I think our ruling-class attempted to disguise their hurt feelings about being rejected with performative contempt and it caught on with the rest of us. Humiliated people will often welcome the news (fake or not) that there are people they are better than.

As an example I’ll cute the widespread belief in this country that US-ers don’t understand irony. Interestingly, I find people are determined to defend this position when challenged and I need to find a new response to this idea. Here’s how the exchange proceeds: A person expresses this belief, I disagree and list 20-30 US wits with a clear command of irony and the person will re-enact the ‘What have the Romans ever done for us’ sketch and say ‘Well, apart from them, Americans don’t understand irony.’ Writing this out lets me see that I have fallen into the trap of supposing that people who are wrong simply lack information.

Hey, guys, don’t know if this is related to the recent technical issues, but it isn’t showing up on iTunes or Overcast.

Other scattered thoughts:-

-Nice comments from our hosts on how essentially *realistic* Revolution is. About the only thing that’s science-fictional about it is the magic sonic-wave device. Everything else is things that have been done and are being done.

And not just in fascist or other authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. Jeff Lester pointed out the close parallels to COINTELPRO (history’s most clumsy sinister acronym) in the US. In the UK, see the Special Demonstration Squad and the National Public Order Intelligence Unit for the UK.

Some of the techniques depicted in Revolution are actually more characteristic of liberal democracies than of actual dictatorships (in which the media tends to be a direct propaganda arm of the government, making some of these complicated games to manipulate it less necessary). This is one of the most disturbing aspects of Revolution.

On the other hand, in some ways, this is a little dated — this is very obviously a story written before we all had our personal surveillance devices in our pockets. Plus, it’s all pre-Tiananmen Square: it’s often been observed, and I think correctly, that what dictators (irrespective of ideology) learned from that was that in the post-1989 era, as long as you had the ruthlessness to kill protestors, it didn’t actually matter if the media images were broadcast or not.

-Graeme McMillan said that he was maybe too young when Revolution came out for the politics.

I’m a little older, and was well into my teens. And I have strong memories of the visceral excitement of talking with my friends in school about Letter from a Democrat and Revolution each week as they came out, the morning after buying 2000 AD. It’s really hard to communicate quite how *important* it felt that 2000 AD was changing and addressing this sort of material.

Honestly, I feel lucky that, as a person of geeky inclinations, I was born exactly when I was, making me the perfect age for the “Biff! Bang! Pow! Comics aren’t just for kids any more,” era. It’s easy to make fun of that time (I just did), but there was something genuinely special about turning from childhood into adulthood in the mid-80s as a comics reader.

Still more scattered thoughts:-

-Our hosts had some great things to say in their deep dive into Dredd’s attitude towards Chopper and what that says about Dredd’s development as a character.

I think there are a couple of things that are worth adding. The first arises out of the following exchange at the end of the Judda strand of the story:

Silver: Such dedication — such drive! Such singleness of purpose! If only it could have been harnessed for the good of the city…

Dredd: Yes. You’ve got to admire the man…

In other circumstances, Judd would have made a first rate Chief Judge.

I think this points up what thematically links the two strands of Oz. “Dedication,” “drive” — the qualities that Silver and Dredd admire in Judd are also Chopper’s. Especially, of course, in his journey from Mega-City One to Oz, but also in his refusal to back down in his final confrontation with Dredd.

I think this jibes rather well with our host’s understanding of Dredd as personally respecting Chopper and not wanting to shoot him at the end. See esp. his remark to Chopper, “Because I know you. You wouldn’t be able to live with yourself.” But this also points to how Dredd’s respect for Chopper has maybe an (inevitable?) sinister edge to it, in how it mirrors Dredd’s own refusal to compromise, and that’s certainly not something that looks good in this volume in general or this story in particular.

There’s another aspect to this, though: this is not entirely a matter of Dredd’s personal respect for Chopper.

“Now get out there — do it for Mega-City One!” (emphasized by being the last panel on the page and also by Higgins’s great use of forced perspective on Dredd’s fist — nice use of a technique that one associates with action scenes outside its usual context). For a moment, Dredd is just another citizen of Mega-City One who finds community in rooting for the national sports hero.

It recalls that great line all the way back at the beginning of Wagner’s Dredd: “The most violent, evil city on earth… but, God help me, I love it.” There’s this sense in that panel that what we’ve actually been reading in Judge Dredd is a love triangle: Dredd loves and almost completely identifies with the Law, but deep down he’s also in love with Mega-City One.

I started reading regularly with The Cursed Earth and have thought for a long time that Dredd was more likely to be flexible, show a little bot more humanity, outside of Mega-City One.

I think there is build to Dredd’s hesitation about shooting Chopper, all the stuff with the doubt about killing Bunt, when he could have disarmed him and the tight boots. It’s interesting that Dredd’s doubts build alongside the presentation of the judicial system as an oppressive one. The judges are an interesting fantasy version of fascism, in that they do not, by and large serve their own interests in the way we commonly understand corruption. They live lives devoid of love or recreation which are relentlessly challenging. They either die in the role, are lobotomised to carry on with their cruel tasks or are set up from childhood to take the Long Walk, if they start to question the system. Their lives end in death or exile. The Long Walk is a brilliant device for social control. Imagine the effects of a group of retired judges with their skills, experience and knowledge who were critical of the system living in Mega-City One?

John Higgins always works hard on his page, but I think he must have been particularly inspired by ‘Revolution’. Those episodes were definitely his best Dredd work to date.

I think we’re quite soon going to come to the point where I stopped reading 2000AD regularly- maybe in the next 4-5 casefiles. I’ve had bursts of reading it since then, when I noticed a particular serial I wanted to follow. There were often other stories I enjoyed, but for a long time Dredd was just so rarely a disappointment and so often a delight, it sustained my interest. I’m looking forward to seeing the decline again and hopefully follow onto a resurgence.