Previously on Drokk!: John Wagner seems to have returned to greatness, judging by the first half of “The Pit,” a massive storyline that places Dredd in charge of the worst Sector House in Mega-City One, pushing him — and the Dredd strip as a whole — into new areas.

0:00:00-0:01:55: It’s time for a relatively speedy introduction, in which we inform you that we’re covering Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 25 this time around, featuring a lot of 2000 AD and a tiny bit of Judge Dredd Magazine material from 1996 and 1997. It’s… a mixed bag, as we make a point of saying.

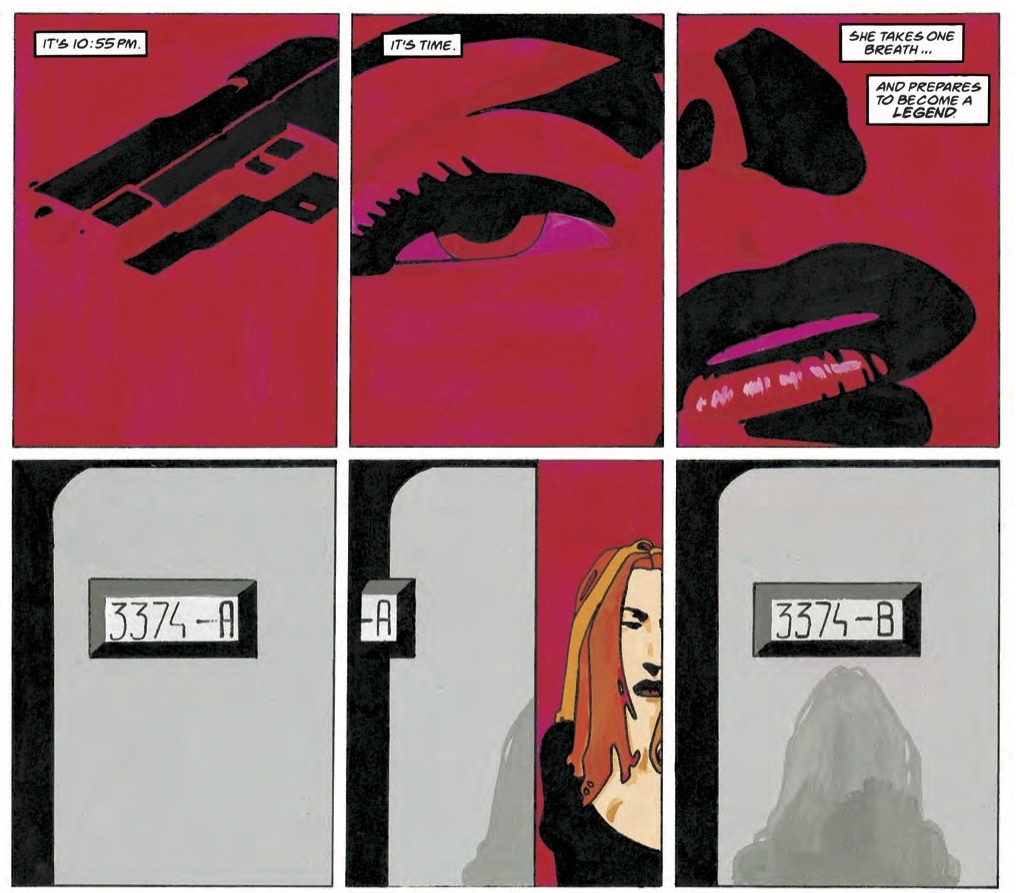

0:01:56-0:20:51: Part of the reason that it’s such an uneven volume is the fact that the Megazine material — which is only four stories — is quite so bad. In particular, we go after Marc Wignore’s work, especially the story “One Breath,” which leads us onto a discussion of what kind of 1990s influence is at play in such a narrative disaster. This takes us into a discussion of the artwork we didn’t like in the book — including Jason Brashill, Paul Peart, and Tom Carney’s chin-phobic turn in 2000 AD. Also under discussion: “Control,” and why why neither of us believe that Judge Dredd would stand by, frustrated, in the circumstances that story places him in.

0:20:52-0:32:58: Turning our attention to the 2000 AD material, Jeff confesses which story is “repellent” to him — yes, he uses that word, and yes, he explains why — before we talk about just how great the final half of “The Pit” is, and explain the reason we’re talking about stories from this volume out of order. (Short version: It starts well and then trails off, and we didn’t want to have an episode that ended on such a downer.) That said, at least there’s “The Pack,” which features something Jeff is scared off, and something else that I love. (Spoilers: It’s Henry Flint’s artwork.)

0:32:59-0:48:44: We disagree strongly about “Darkside,” the 2000 AD storyline from John Smith; I’m unconvinced by what I see as an extended exercise in nostalgia and a lot of near-Morrisonian cliches, but Jeff has a grand theory as to why those flaws are sidestepped to create a meta-commentary on the state of fandom and popular culture that is a quarter century ahead of its time. (I remain unconvinced, I admit.) The rare schism when it comes to Dredd!

0:48:45-1:09:16: We double back to a couple of our favorite stories from this volume: “The Pack,” where the lure of flying sharks that eat people and cause shit proves to be irresistible, and “The Pit,” where Wagner seems to be pushing Dredd as a character and as a strip, in interesting directions. Those directions, and what they ultimately become in the future of the strip, are discussed — get ready for the comparison between Wolverine and “Judge Dad” — as is the fact that what feels like an evolutionary step comes to a sudden halt, only to be replaced by a series of episodes that feel almost retrogressive in comparison. Whatever happened to the Judge of Tomorrow?

1:09:17-1:23:24: “Dead Reckoning,” the serial that immediately follows “The Pit,” is a rare misfire for John Wagner in this era. A large part of that, if you’re Jeff and I, is that it’s a story that centers around Judge Death, who is a particularly dull villain that has arguably run out of steam, especially in this era. Jeff is similarly unimpressed with “Death of a Legend,” the one-off that closes out the McGruder storyline once and for all, but I’m more of a fan — in part, as Jeff puts it, because I’m far more sentimental about these kinds of things because I’m Scottish. (Look, he’s not wrong, he even calls me out correctly for loving the many John Lewis Christmas ads!) One of the reasons Jeff doesn’t feel as favorably about it is that he’s less convinced that McGruder is a fully-formed character, making emotional connection and sentiment particularly unearned. He might not be wrong, to be honest.

1:23:25-1:37:29: As we near the end of the episode, it’s time for that very special question: Drokk or Dross? We both come down on the side of Drokk, and have the same choices for our favorite stories in the collection: “The Pit” — and, really, the “Unjudicial Liasons” episodes therein — for our favorite Wagner-written, “The Pack” as a runner-up, and “Darkside” for the best non-Wagner story. Yes, even though I wasn’t really a fan; it’s still better than all of the Magazine material.

1:37:30-end: We wrap things up by briefly looking ahead to the next volume — more air sharks! — and offering the traditional mentions of Instagram, Twitter, and Patreon. As always, thank you for listening and reading; we, and Mega-City One, appreciate it greatly.

And for those looking for the direct link… http://theworkingdraft.com/media/Drokk/DrokkEp28.mp3

Funny Jeff mentioned Duran Duran in reference to Marc Wigmore’s art, as Patrick Nagel had crossed my mind as maybe being in the melange of Pop Art influences he was drawing on. I was surprised by your preference for Alex Ronald’s work over Lee Sullivan’s. I’m far from a fan of Sullivan’s comics, but there is a competent sense of composition and movement in his pages. Ronald’s isn’t too bad to start with, but by Bongo War parts 2-4 there’s an increasingly desperate use of the dutch angle to try and introduce some interest into some pretty static pages. To be fair, it’s easy to imagine being anxious knowing Ezquerra has chapters of the same story. I really noticed how Ezquerra was using some of the composition within his panels to steer the eye to the next panel, especially where the action was fierce.

Hard agree on enjoying Flint’s art. It great to see someone who takes influence beyond surface and learns from a masterful storyteller.

One thing not included in this collection are the covers. A Short History of Female Judges in Judge Dredd talks about the controversy the cover to prog 987 started and some of the complaint letters folks sent in about it. Definitely a case where editorial and writing were in different places: https://judgeanon.tumblr.com/post/152728330405/a-short-history-of-female-judges-in-judge-dredd

Scattered thoughts:-

-It’s interesting to compare this choice of a Dredd story for #1000 with the one chosen for #500. In #500, Wagner and Grant told the generally rather bland and ordinary story of the murderous mentally ill masseuse, which felt like a conscious choice *not* to celebrate the 500th issue. If so, now Wagner capitulates and gives the reader what they would expect for a celebratory Dredd story, I’m afraid.

Although even if he is capitulating, Wagner remains marvellously efficient as a storyteller. “Am in pursuit” — that’s just a great little moment that encapsulates so much about who Dredd is. I said something like this last time, but this is a better example: with three words, Wagner makes Dredd seem so much more tough than all of Ennis, Millar, and Morrison could manage with all of their posturing dialogue put together, and at the same time makes a joke about just how insanely blasé Dredd is about everything — presenting Dredd as impressive and sending him up at the same time.

-Our hosts commented on how the post-Pit stories dial back on Judge Dad (a great coinage). One further instance that really jumped out at me was the conceit of Dredd instantly being suspicious and searching someone for being happy, which is certainly a classic moment reminiscent of ‘80s Dredd.

-I didn’t dislike the Megazine stories as much as our hosts. This may be because there weren’t all that many of them, as I can certainly imagine that their lack of substance might have been harder to take if it had gone on for longer. But I think that a lot of it was because they felt like Future Shocks that happened to be Dredd stories and not actual Future Shocks, things that were meant to be light and throwaway.

Frankly, the worst thing in them, for me, was something for which John Wagner was responsible: ”He is a legal weapon.” I don’t know what you think that does, Mr. Wagner, but whatever it is, it’s not doing it.

-“Return to Hottie House” makes for an interesting juxtaposition with “Awayday,” from my perspective of being interested in what Dredd says about British identity and its relationship to America.

Look at the language that Wagner gives Dredd and the Branch Moronians in the first story. Examples: ”This lot seem a bit smarter.” (Dredd); ”Ya shoulda writ it down on a piece of paper, Brother Cliff, like ya done them other things.” This is a trick that Wagner has done before, give Dredd “normal-sounding” (= British English) dialogue and set is side-by-side with parodic American dialogue (here fairly overtly modeled on pop-culture versions of Appalachian English). I.e, this is a place where Mega-City One’s ostensible status as future America is shoved into the background and Dredd is presented as the sensible British person confronted by a distinctly American kind of stupidity.

And then we have Awayday., which confronts Dredd with someone from Brit-Cit. The language shifts to match. That Judith Glutt speaks in, well, BCBC English is obvious and unsurprising. But here is how Dredd now talks. ”Control, you got two for the meat wagon, two for the cubes, Ten years, no remission.” It is, obviously, a *lot* more subtle than in Return to Hottie House, but Wagner gives Dredd a distinct American turn of phrase, both in “you got,” but more generally in the stereotyped laconic quality — the sort of thing that gets American English labelled as “muscular.”

Interestingly, Dredd dials this down and is a little more expansive and British when he’s talking to Glutt, as if he’s ironically matching his language to hers. ”Not quite, There’s the little matter of the assault charge.”

But anyway, it’s a good example of how Wagner is solid on paying attention to how little choices reinforce the story. And what is the story in Awayday? In contrast with Return to Hottie House, this represents Americanness as superior to Britishness (although one might possibly in this case more accurately say southern upper-middle-class Englishness). Silly British people — well, a certain kind of specific English stereotype, anyway — just wouldn’t able to cope with tough American reality. This is a very different take on the same themes as the Kenny Who? story, in which a naive but sympathetic Scottish everyman is destroyed by trying to make it in America.

That the British person is from the media and manufactures “documentary” appearances is significant — the story is built around the contrast between Glutt’s effusive onscreen presentation of Mega-City One and how completely she falls apart when she has to deal with the real thing. From this perspective, it is telling how Dredd appropriates Glutt’s language back at her, and especially his use of irony — which British people have been known to pride themselves on being better at than Americans. Dredd controls the gulf between language and reality in a way that Glutt simply can’t.

And — this might be something that gets me driven from these comments — I might venture that John Wagner has maybe even learned a little from Garth Ennis. Because pre-Ennis, Wagner was very slow to bring Brit-Cit into Dredd at all, and the closest he came to approaching it in a way that had some content to it was the safe Edwardianish stuff in the Alabamy Blimps story. Now he actually engages with something from contemporary Britain. Admittedly, it’s not all *that* contemporary: Holiday had been broadcast since (checks Wikipedia) 1969, meaning that Wagner could have done this joke any time in the entire existence of 2000 AD. But baby steps, Mr. Wagner, baby steps.,

‘Apalachian English’ – pretty sure I can discern the root of ‘billy’ in ‘hillbilly’.

Worst art in this case files goes to Alex Ronald. The way he aggressively obscures the action in every other panel by placing a character with their back to the reader was as awful as it was comical. I don’t know if it was his failed attempt to frame the stories from a bystander’s perspective, but the only way it could have been made worse is if the pages he drew reached out and gave you paper cuts on your eyeballs.