Previously on Baxter Building: Forget about your previouslys, because this episode we’re jumping through the years to cover four different annuals we’ve left untouched until now, from 1985 through 1991. What is time, anyway…?

0:00:00-0:07:17: In an attempt to catch up on the backlog of ignored annuals — and also try to put off the start of the Tom DeFalco/Paul Ryan run just that little bit longer — we’re covering Fantastic Four Annual #s 19, 22, 23 and 24 this time around. (We covered Annuals 20 and 21 in episodes 34 and 35, for those wondering, because they tied in directly to the Steve Englehart run in the regular series.) Given the quality of these comics, that may have been a bad idea, but before we get there, we talk briefly about annuals and what they used to mean for the Marvel line.

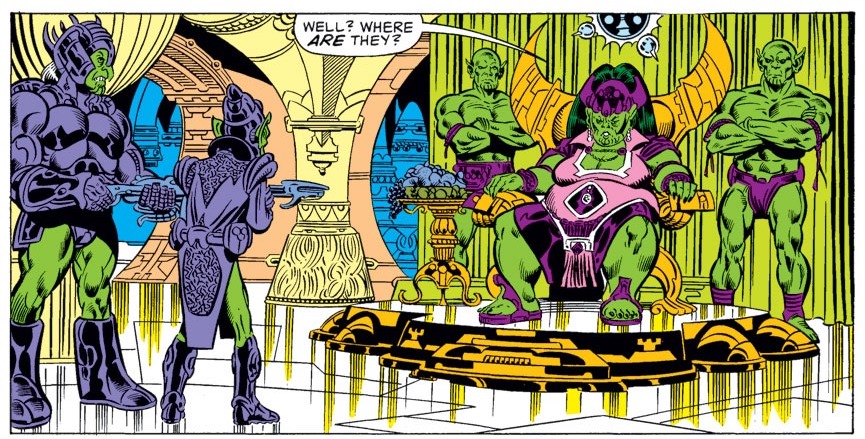

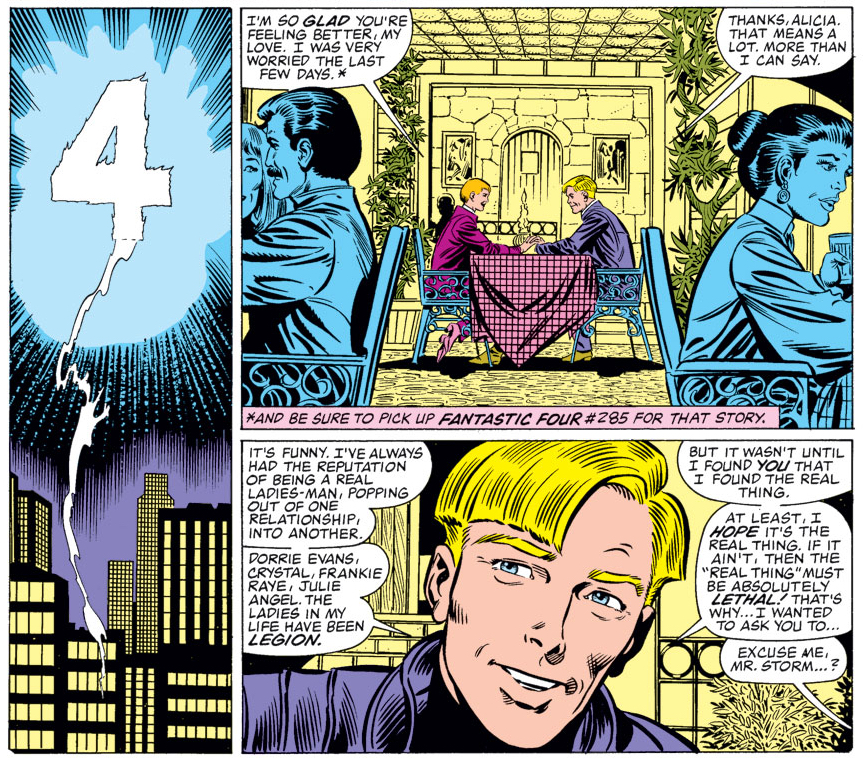

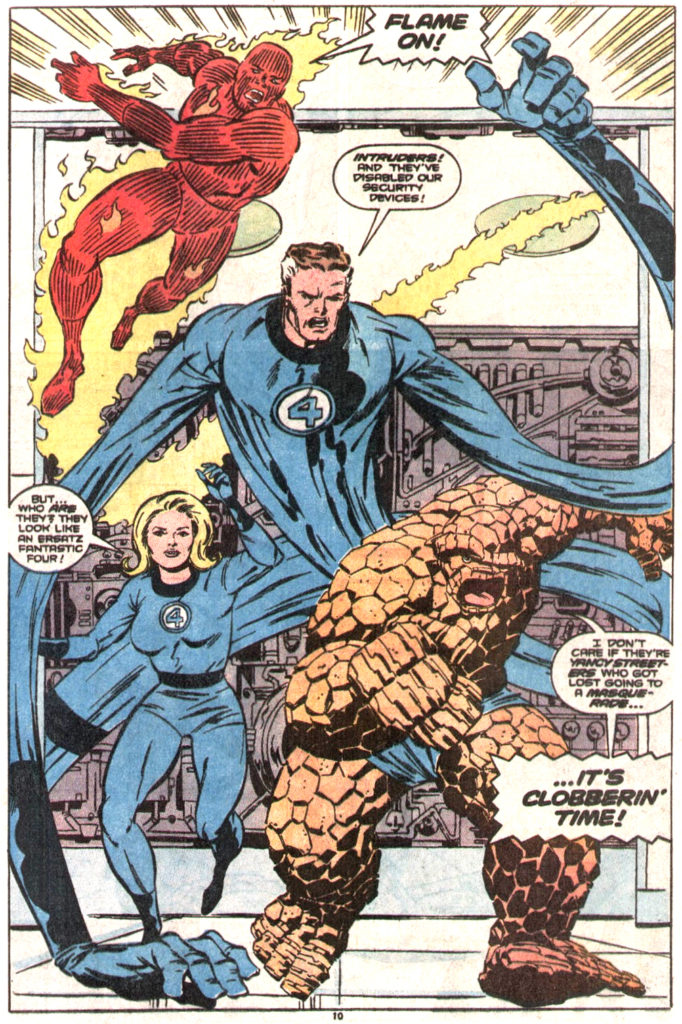

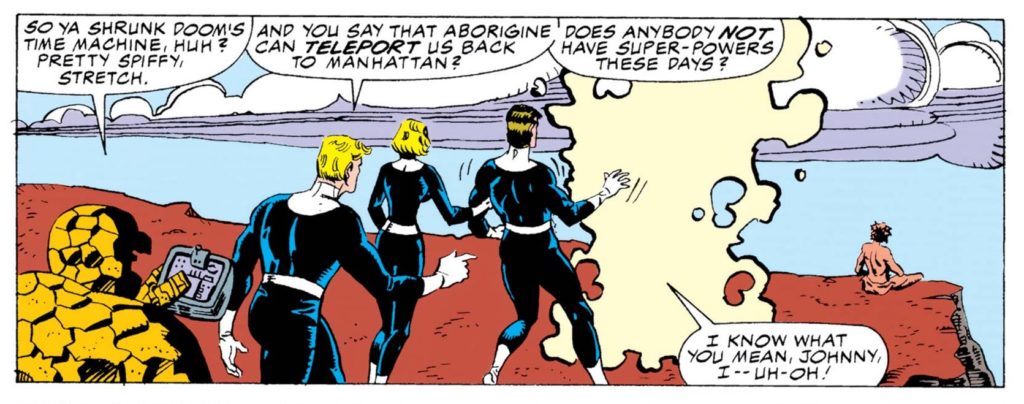

0:07:18-0:36:40: We begin with a blast from the past — and I’m not talking about the quasi-return for the Enfant Terrible. Fantastic Four Annual #19 is an all-John Byrne issue — with Joe Sinnott inks, to boot — and that means that we get a refresher course in all his particular quirks. (Those of you who like the hyper-competent, impossibly-correct Reed Richards, prepare to get excited.) Under discussion: John Byrne’s painfully slow pacing, the unexpected choices of Skrull shapechangers, differences in inking between Kyle Baker and Joe Sinnott, and why this comic is just like a movie by M. Night Shyamalan.

0:36:41-0:54:04: If 1985’s annual left us unimpressed, it seems like Lee and Kirby compared with Annual #22. The final chapter of the 14-part Atlantis Attacks is no-one’s finest hour, and barely a Fantastic Four comic at all, but it does feature some almost impressively heavy exposition and unsubtle dialogue as the idea of characterization is seemingly abandoned in the name of just getting to the end of the story at any cost. (Of particular concern, Dr. Strange and Reed Richards, as we go into.) Compared with this, the back-up strips shine, but Jeff doesn’t know that because, inexplicably, neither of the FF-related back-up shorts are included in the Marvel Unlimited version of the issue, meaning that I have to give a brief plot summary of both to explain why they’re worth hunting down. (Hilary Barta alone should get people excited, I think.)

0:54:05-1:22:48: There’s a lot that’s wrong with Fantastic Four Annual #23, not least of which being the fact that it’s pretty much a bad X-Men comic that just happens to star the Fantastic Four. This brings Jeff to the conclusion that the first chapter of “Days of Future Present” is, in fact, a meta-textual “Days of Future Past” that reveals the post-Chris Claremont era of Marvel’s X-Men line a year before it arrives. Considering that X-Men editor Bob Harras scripted the main story in the issue — a fact actually hidden away on page 23 of the story, amazingly — this might not be a coincidence, admittedly. If the primary story doesn’t impress us, there’s a pleasant surprise in the back-ups, as James Brock’s Volcana strip feels like a solid first issue of a mid-range comic, while Jeff is far more taken with the cosmic travelogue offered by Kubik and Kosmos than I am. I blame his long-standing fondness for Jim Starlin comics. (Also, in explaining away the end of “Days of Future Present,” I accidentally say that Franklin has ghost powers; I meant to say he has dream powers, and that Adult Franklin is hijacking them. My mistake, by which I mean, oh God, these comics are so bad.)

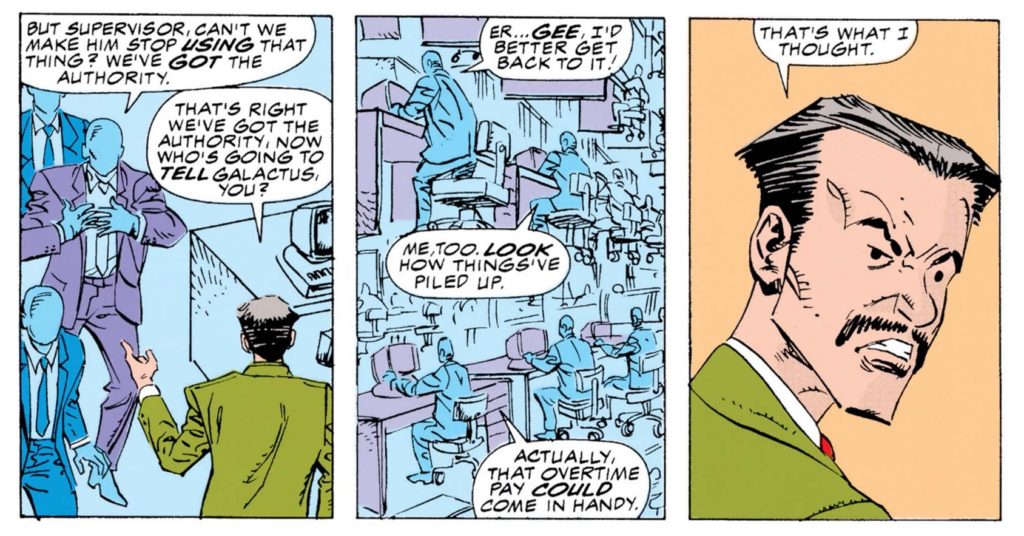

1:22:49-1:49:01: By the time we get to Annual #24, both Jeff and I are pretty exhausted by the crappiness of what we’ve been reading, but not to worry; there’s the first chapter of an entirely unnecessary sequel to the Avengers storyline “The Korvac Saga,” which is not only written, but also pencilled and inked by Al Milgrom. (As we say, he tries to channel Simonson in scenes featuring the Time Variance Authority; Jeff thinks he nails it and I most certainly do not, but look up and you tell us.) Continuing the theme, this isn’t really a comic about the Fantastic Four, but when I tell Jeff the way the storyline ends in another comic, it’s fair to say that he couldn’t care no matter who it’s about. Luckily, there are back-ups, including a second (admittedly lesser) Volcana strip and a Super Skrull short that gets us all bothered about why it even exists and who it’s intended for. Are we too grumpy? Don’t blame us; these are very bad comics.

1:49:02-2:12:59: In fact, they’re so bad that Jeff returns to his comment from a couple of episodes ago about whether or not he even likes the Fantastic Four, and turns it on its head: Do these comics prove that Marvel doesn’t like the Fantastic Four? Or, at least, that it doesn’t know what to do with them? We talk about the lack of Fantastic Four in these comics compared with the Steve Englehart Annuals we covered earlier, and also about the lack of focus on the characters even when they do appear. Is this a sign of the Image-ization of Marvel that was happening at the time, or something else? (And, in a tease of what’s to come, I bring up the idea that the Fantastic Four comic’s specific response to Image is what forever doomed the book to be seen as a retro title, but the proof of that pudding is yet to come.)

2:13:00-end: We wrap things up with promising a new Wait, What? in two weeks and invite everyone to send questions for a special Q&A episode. Send us an email or tweet at us; you can also send us a message through Patreon if you’re a Patreon Patron and that’s your speed. As ever, we also remind people about the Twitter, Patreon and the Tumblr, and then Jeff’s ever-friendly tones walk us out. Thank you, always, for reading and listening. Now, send us questions!

For those looking for the direct link, look here: http://theworkingdraft.com/media/podcasts2/BaxterBuildingEp41.mp3

I haven’t had a chance to listen, but I always took that odd Harras credit to mean that he scripted pages 23 onward and that Walt did the first half (still a lousy issue, though!)

I have a few random thoughts:

I believe it was during Jim Starlin’s Silver Surfer run that they solved the shapeshifting thing. Starlin’s run was very much in the same tone as Englehart’s, so they blend together. I genuinely can’t remember how they did it, but there was some kind of weird liquidy Skrull Jesus who could give powers back to the others.

There was also a male Skrull who got trapped in a female alien body when he lost his transforming power. He was worried whether his wife would still love him, but she reassured him that she didn’t care about his outward appearance. Then she murdered him because she was now the Kree Empress and needed to kill all witnesses that knew she was a Skrull.

Regarding Roy Thomas’s Doctor Strange, I read his tie-ins for Infinity Gauntlet. He was a very glib character, so I’m sure he was consistent with that character in the FF Annual.

I’m going to offer a forceful and spirited defence of FF Annual #19 as being fabulous and wonderful.

If you read it in Marvel UK’s Secret Wars II comic and were very young at the time.

I’ve talked about it before, but for North Americans who are looking at this comment strangely and (a) wondering if they should call the authorities about this obviously crazy person and (b) saying, “This isn’t part of Secret Wars II. It’s not even a tie-in”: the Marvel UK approach to reprinting Secret Wars II made it a very different thing from what those words mean in North America.

The approach adopted was to print the miniseries, and all the tie-ins, and what they felt was necessary to make the tie-ins work as reading experiences, both in terms of continuity and in terms of giving the reader overall stories, even if those stories had nothing to do with the Beyonder, The latter was fairly obviously was taken as an excuse to throw in anything that the editors thought would sell. This week, we check in with Daredevil; next week, Thor.

Given that there were a fair number of “red skies” Beyonder appearances in other storylines and the liberal attitude to what should be included, you could be tracing many, many issues worth of unrelated stories, just because the Beyonder appeared in a couple of panels somewhere in one issue.. It wasn’t quite as extreme as that probably makes it sound, because there were characters that weren’t given much attention, with only their actual tie-in issues featuring (with text pieces at the front to bring the reader up to speed). But then there were others that appeared over and over again, and the FF and the Avengers were among the things that the editors clearly thought would be big sellers, because there was a lot of both in the comic.

So that what you really got was this comic that was offering you stories from all over the Marvel universe, loosely unified by (a) the recurring figure of the Beyonder and intermittent appearances of the issues of the miniseries and (b) the ongoing storylines of those comics that were chosen to appear a lot. The Nebula arc in Avengers was one of those, a storyline that you read over several issues. (I have a vague memory that this was “justified” by the Beyonder popping up in a space battle briefly at some point, but it’s been a long time.)

All of this material was placed on a level, as if it was all part of the same comic, one issue after another. The result was that you were presented with what was in effect something like superhero Bleak House, a huge sprawling single story composed of all these different, meandering, intersecting storylines, featuring different characters, with the Beyonder as Jarndyce & Jarndyce.

It must have been one of the most challenging editing jobs in the history of Marvel UK, and it massively improved the original source material by transforming it into a very different reading experience. Especially if you had been dependent on Marvel UK for your consumption of superhero stories, because that meant that you were only ever getting a small number of stories from what you knew was a much larger set of comics being published in the US, and often not in order (there was a lot of reprinting of older material). MUK SWII felt like you were going from getting scraps here and there to reading about a whole coherent universe, kind of as if you were a historian studying a period that had suddenly emerged from some sort of dark age with few records into one with a plethora of evidence from which to understand what was happening.

That’s the context in which these Avengers and FF Annuals seemed to me (and I was very young) the best thing ever. Because it’s the best moment of intersection in an overall story that had been rebuilt around intersection. You had followed the Nebula storyline for a number of issues, and you had also read a lot of Byrne’s FF, and suddenly, you were presented with the same scene in both storylines from both perspectives.

I think that’s a narrative device to which comics are better suited than other media. On the one hand, the fact that it’s perspective matters: this works better in a visual medium than it does in, say, a novel. On the other, in e.g. film it’s hard to juxtapose the two scenes, while in a comic you can flip back and forth. And serialization helps, because you can set them side by side. I’m pretty sure that this was the first time that I encountered the device in a comic, and it made a tremendous impact on me.

The other thing about MUK SWII is that the original American material was edited down and recut for faster-paced British weekly publication. I don’t remember if FF Annual #19 was split over two issues, or if they simply took a really thorough hatchet to it. I suspect that also improved it.

The X-Factor annual in Atlantis Attacks had John Byrne inked by Simonson, which was of some interest to me as Simonson so rarely inked others. Otherwise I hadn’t read any of these before. My younger self had some good ideas where the management of time and money were concerned.

So Byrne was making some break-up of the Soviet Union metaphoric point in how he was approaching the collapse of the Skull Empire? Or am I giving him unnecessary credit? Certainly the history of our times shows that the end of an oppressive regime doesn’t mean we don’t get something worse.

There are things I like about Al Milgrom’s art in the Korean story. He is clearly riffing on Simonson -including an explosion which to my eye is very much early 70s Simonson, rather the than late 80s vintage. Still the storytelling is clear and more imaginative than what I expect from him. What I’ve never understood is what he’s aiming for when he inks himself. His inking on others is variable, usually competent, sometimes excellent and sometimes disappointing. When he inks himself though, he makes marks I just don’t understand. Any insight, anyone?

I was interested in your discussion of the Image revolution being a group of young creators reacting against the stultifying editorial environment exemplified by these very dull comics. It’s an interesting perspective on it. I read annual #25 as well, which shows some of the flakes responses Marvel editorial fostered post-revolution. Herb Trimpe trying to draw like Rob Liefeld and do the hyper-sexualisation is pretty dispiriting.

Three things!

1. I’m glad you liked the Volcana stories. I too found them weirdly charming. It looks like James Brock did another Volcana story in Marvel Comics Presents #88, so I might try to hunt that down.

2. I think that the backups from these annuals probably aren’t on Marvel Unlimited because the stories might have been digitized for inclusion in omnibuses and other non-Fantastic Four collections. (For example, the Korvac Quest is reprinted in the Guardians of the Galaxy by Jim Valentino Omnibus and doesn’t include any of the backups.)

3. What’s even weirder about that Super-Skrull story in annual 24 that is a follow up to a Silver Surfer storyline is that the Silver Surfer Annual (which features part 3 of the Kovac Quest) ends with seven pages of pinups, so they probably could have just printed the story there. (I guess there’ might be a slight page count mismatch, but who knows.)

Having finished listening to the podcast, some thoughts about our hosts’ discussion towards the end of whether it peaks with Lee/Kirby, making everything inferior to that:-

Yes. I think that is completely correct. There are some enjoyable runs after that. I think well of the Waid/Wieringo run, for instance.

(Then again, part of why that works is, I suspect, because Waid doesn’t have much nostalgia for the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four, so that he’s not trying to revive that feeling, just looking at these four characters and this setup and asking, “What stories can I tell about these guys?”)

But it’s never “special” after Lee/Kirby, never more than “reasonably good comics.” There’s not a single run after that, that one can call *important* (as superhero comics go). I think this distinguishes the FF from the X-Men – the X-Men still manage to have good runs on a more consistent basis, and there is one run post-Claremont (Morrison’s New X-Men) that I would call important.

But where I would disagree with our hosts is that I don’t think that it’s solely a matter of what Kirby did and then how Lee added the right bit of extra flavoring to that. Or rather, I think part of what was brilliant about Kirby is that he goes beyond just what he brings to the comic from a visual and storytelling perspective — Kirby had this marvellous ability to engage in interesting ways with the broad story of American culture at whatever time he was working.

Yes, it’s that thing that I’ve said before, that the Fantastic Four are quintessentially about the ‘60s, especially the early ‘60s, and they work so well because *Marvel* was an important part of the pop culure of the 60s.

There’s all the ways in which these characters are part of that era. One thing about the films is that neither of the film versions that I’ve seen (ignoring the Roger Corman version) finds a good replacement for the fact that the FF’s origin is tied to the space program.

Johnny Storm is a bland character, whose traits amount to “hotheaded teenager who’s really into cars.” But that “generic teenager” quality makes him an iconic early-60s figure, at the time when teenagers had only recently been invented as a distinct age group and had just cemented their commercial dominance of music and other media. Compare Johnny to Snapper Carr in Justice League and you will cringe with embarrassment on DC’s behalf at just how much sensitive the Lee/Kirby image of an early ‘60s male teen is. And this is about Marvel and how it comes to appeal to an older teenaged audience – it’s commenting on the culture that it’s also participating in.

(I am slightly tempted to argue that ‘60s surf culture is why the Silver Surfer isn’t silly, but the Black Racer is. But let’s not push it.)

Overall, the Fantastic Four is, I think, about an optimistic future, but with the idea that the future is coming into being in the present. That’s why they all look like they’re part of what is now a very dated Star Trek vision of the future in which everyone will wear tight clothing (which is obviously about turning ‘60s fashion up a notch) and live in a technological wonderland. This is the ‘60s – it’s that idea that a new generation is coming of age that’s going to do things better, that anything is possible, that “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is a decisive moment in the history of Western civilization.”

This is one of the things that makes Doctor Doom work so well as the antagonist, because he’s got that medieval aesthetic about him that represents the horror of being trapped in the past despite having all these technological wonders. Of course, the first thing that he does is send the FF back in time.

And the fact that the comic is also doing new things in superhero comics is also part of the way in which it’s about the ‘60s, so that formal features are underpinning the way in which it is engaging with the culture that it’s also helping to create.

As I’ve mentioned before, I don’t think that any of that works as well once you enter the psychedelic era. And it’s all horribly dated now, because it’s positively retrograde, not forward-looking. Take Reed, for instance. Reed is like Captain Kirk. At the time, Captain Kirk wasn’t what he appears to be now (in the films, especially) an irresponsible sexist Casanova child-man who probably shouldn’t be in command. He was the ideal commanding officer, a voice of moral authority. Similarly, while Lee (and Kirby can’t be completely excluded) wrote Reed as an unpleasant jerk, they didn’t think they were writing him as that. He was the wise scientist, the older guy who’s still engaged with the future that Science! is bringing into being.

(Sue is just The Girl, because, you know, the ‘60s.)

Now in the mix you do have Ben Grimm, who’s different. One of the great characters, more than a product of his time — and about (coded) working-class Jewishness, and so not confined to the same themes as the others.

But aside from Ben Grimm, what is there here that’s going to work well outside of its original context? I don’t know that there is anything, because I don’t know that the future that the Fantastic Four represent is alive any more. But, you know, maybe it should be. Or an updated version of it, at any rate. Maybe one can do something with all the ways in which an optimistic future that’s coming into being, that’s almost here, feels oppositional and different.

There’s a problem there, because a contemporary version of an optimistic future that’s just around the corner really can’t be based in three white people and a person who can be coded as nonwhite, but only at the substantial cost of saying that nonwhite people are a lot like orange rock monsters.

Nothing can be done about that, realistically, except write a different comic. So supposing that one has to do something with the FF, here would be my vision of the FF, if I knew the first thing about writing comics.

The FF are the best we can imagine tomorrow being and the best we can imagine becoming. They are pioneering a lifestyle that is ecologically non-damaging, that, when it is generalized, will enable us all to avoid catastrophe. They dress, not in their traditional costumes, but in clothes that represent a brilliant artist’s best guess at where fashions will be in a decade’s time. They use the Internet and social media in a way that is everything good that those things can be. They are activists who serve as symbols for people all round the world that a better way is possible, if we only work together. All this is grounded in things that people are actually working on now.

Personally, they are kind, decent, and utterly comfortable with difference. They co-operate and love one another. Ditch the whole “dysfunctional” soap opera. It worked brilliantly in the ‘60s, because it was part of what made Marvel comics feel so new (and so ‘60s). But it’s no longer *new*.

Reed is depowered. If there were ever a character suited to be the”guy in the chair,” it’s him. Sue is the leader in the field. Johnny is passionate, and it may get him into trouble, but he’s passionate about fighting injustice, not about personal things. Ben stays Ben, obviously.

They fight entrenched interests, but on a cosmic scale. They are not just saying to their fellow humans that a better way is possible, but they also stand as a rebuke to the whole feudal space-opera character of Marvel’s various alien empires. There’s a whiff of Bank’s Culture novels about them. The various alien threats are linked to the ones on Earth because they’re the same thing. The earth has long since been taken over by aliens (see: http://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/2010/12/invaders-from-mars.html) and the Fantastic Four are here to fight back.

I really liked what you said about Ben’s working-class Jewishness. It sparked a thought about his specifically upwardly mobile working-class identity. Even if he had never become the Thing, as a college educated uptown guy the Yancy Street gang would still have razzed him. Viewing the relationships in the FF though the lens of class is enlightening as well- owning class Reed, the middle-class Storms, it all fits. I accept the idea of the FF as family, but enjoy the idea of another level on the price of membership for Ben is the loss of a wider sense of community.