To look at the collected editions — or the creative teams for that matter — Before Watchmen: Ozymandias and Before Watchmen: Moloch don’t naturally belong together. The former is written by Len Wein and illustrated by Jae Lee, while the latter is by J. Michael Straczynski and Eduardo Risso, and while both are technically origin stories, it’s not as if little Adrian Veidt shows up in the same school as Edgar Jacobi. So, why do they belong together in this series…?

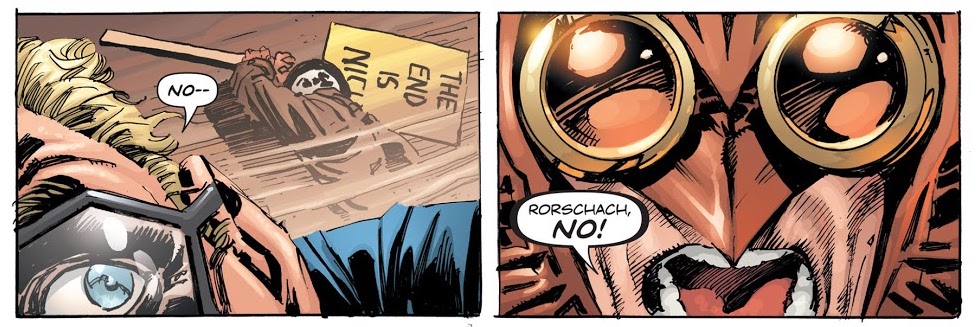

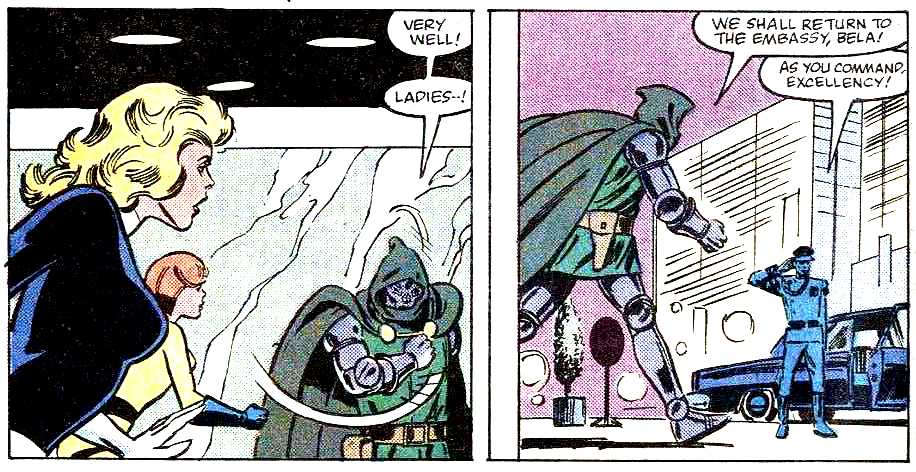

The answer is twofold. Most obviously, it’s that the two series literally crossover, or at least cover the same ground to a brief extent — namely, Moloch’s involvement in Veldt’s plot to bring about world peace by nefarious, ridiculous means. (Both series include variations on the scene where the Comedian confesses to Moloch in his bedroom, from the original Watchmen, curiously enough.) Maybe more importantly than that, though, it’s that both Moloch and Ozymandias take the prequel brief of Before Watchmen perhaps a little too literally, with final pages that literally lead up to particular scenes in Moore and Gibbons’ original book, after spending far too long explaining things that those who’ve read the original book already know, in exhausting and depressingly literal detail.

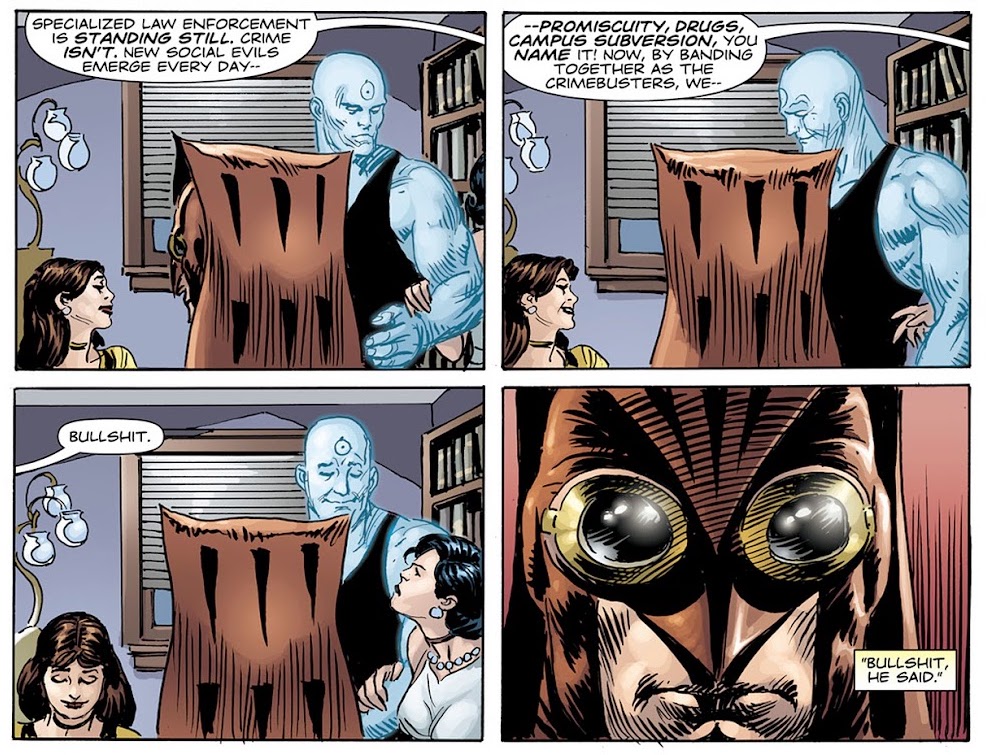

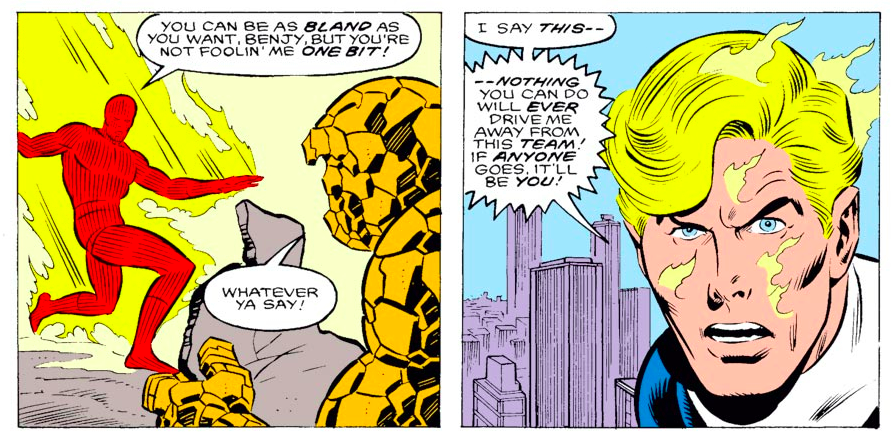

It’s no surprise, perhaps, that Ozymandias is the bigger offender of that latter sin, if only because, at six issues, it has more real estate to fill than the two issue Moloch. But Ozymandias is far worse than merely being longer than Moloch — it’s a perfect illustration of the problems with this approach to prequels, because at some point, it goes from an utterly unnecessary exploration of Veidt’s childhood and early crimefighting career, complete with unlikely meetings between the primary Watchmen characters, to essentially Adrian Veidt Explains All Of Watchmen In Case You Didn’t Understand It The First Time.

It’s no surprise, perhaps, that Ozymandias is the bigger offender of that latter sin, if only because, at six issues, it has more real estate to fill than the two issue Moloch. But Ozymandias is far worse than merely being longer than Moloch — it’s a perfect illustration of the problems with this approach to prequels, because at some point, it goes from an utterly unnecessary exploration of Veidt’s childhood and early crimefighting career, complete with unlikely meetings between the primary Watchmen characters, to essentially Adrian Veidt Explains All Of Watchmen In Case You Didn’t Understand It The First Time.

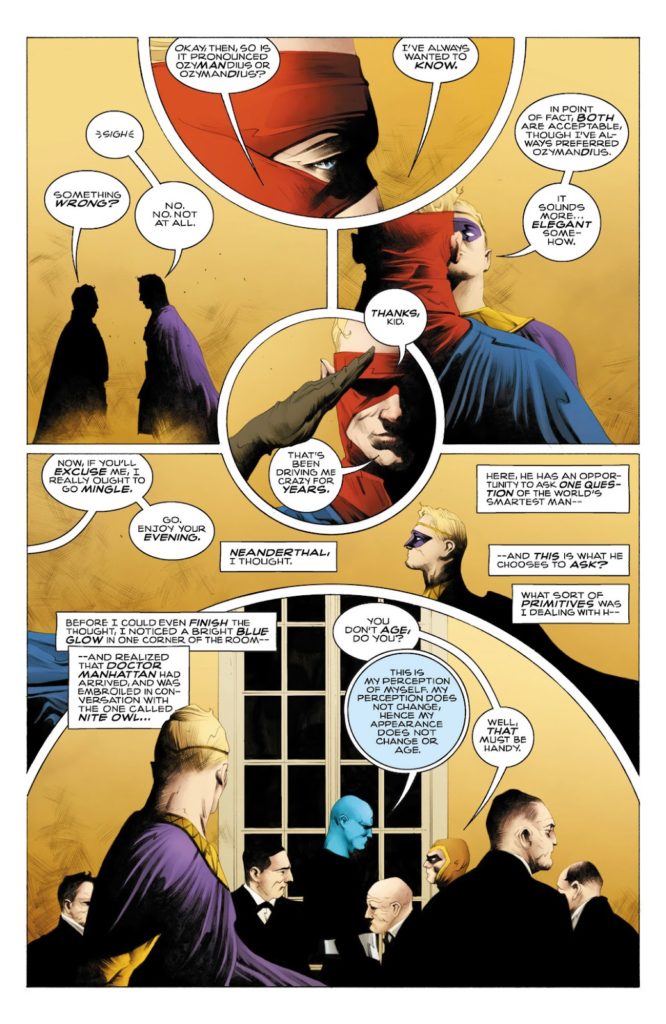

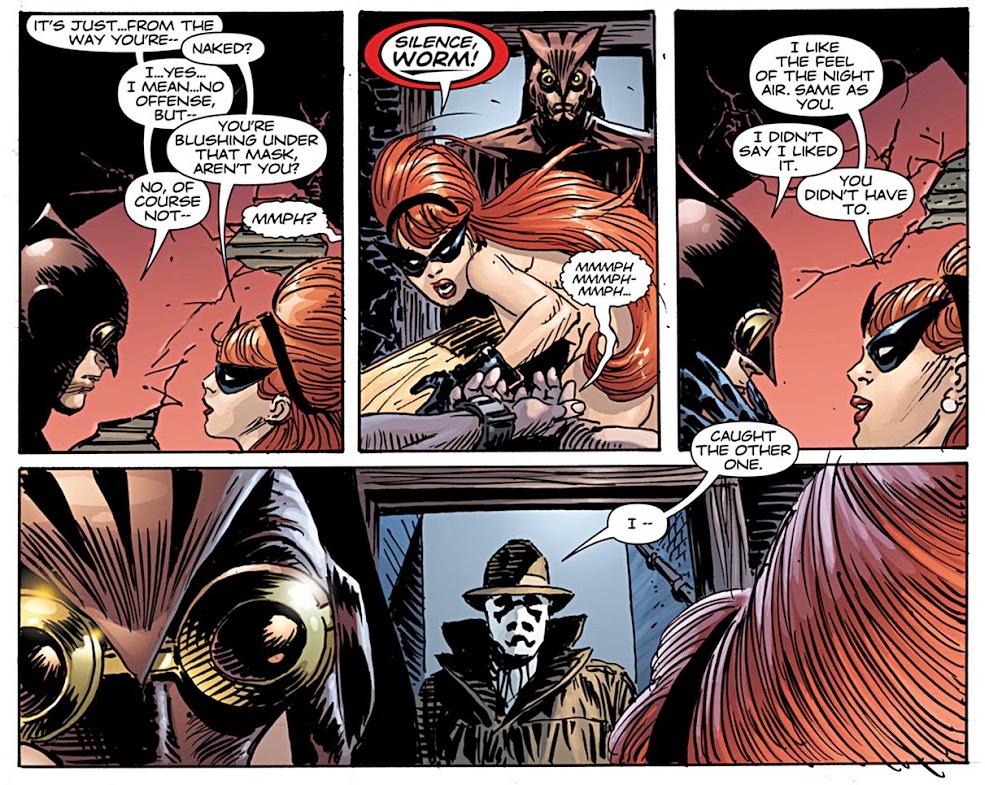

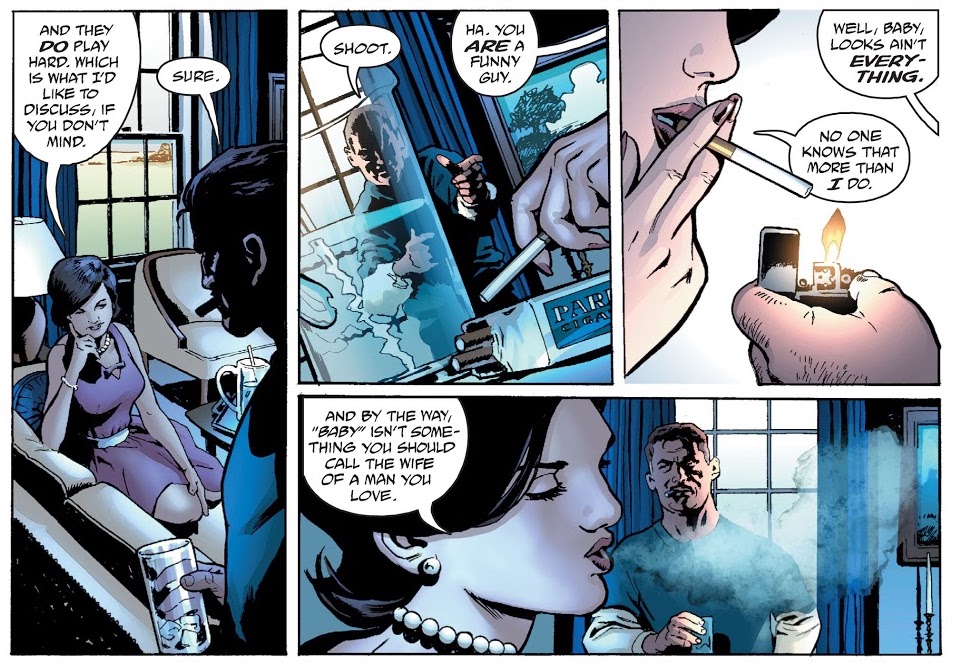

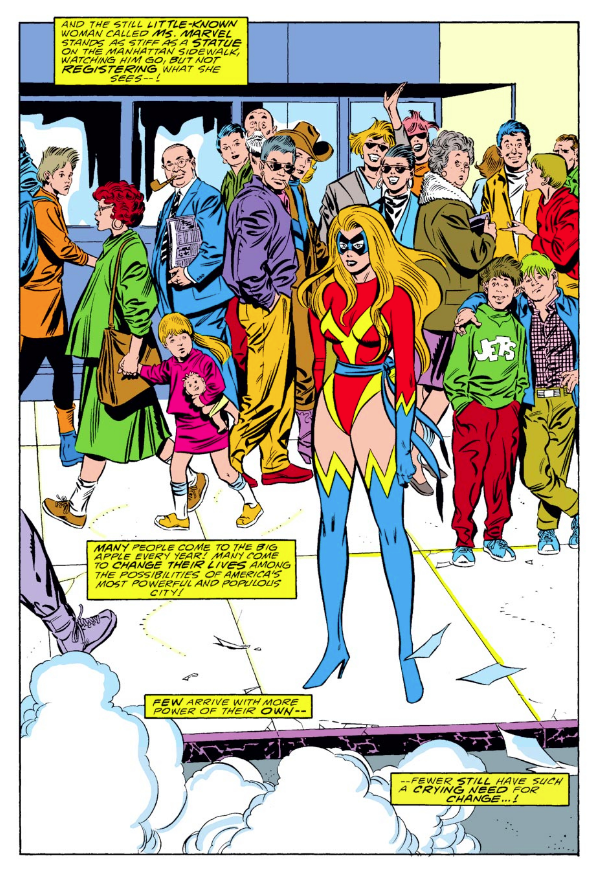

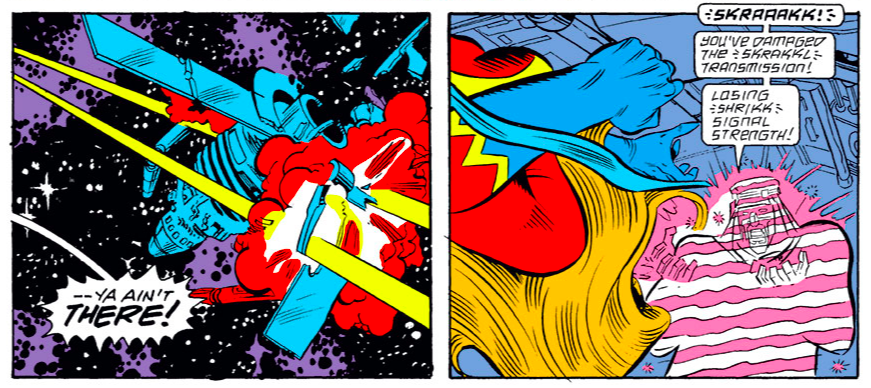

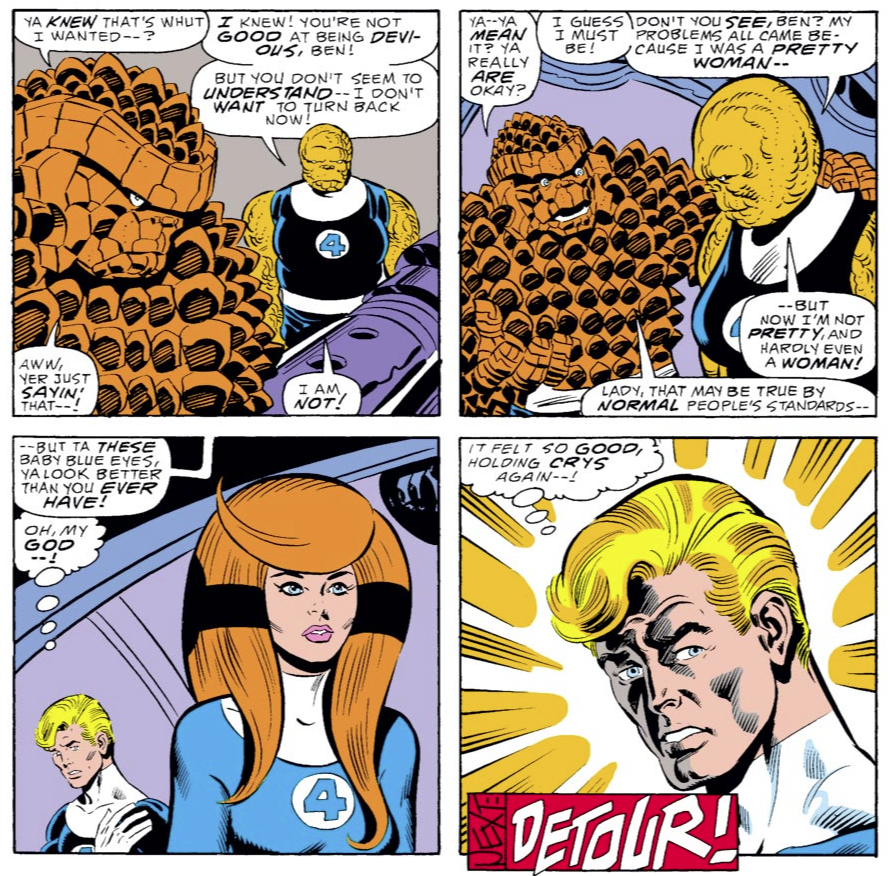

To call this pointless would be too harsh; after all, there is some genuinely beautiful Jae Lee artwork to help everything out, with his fine linework and exquisite page design offsetting his seemingly permanent disinterest in drawing backgrounds or being aware of where characters actually are in a physical space at any give time. It is a lovely looking series despite that, with Lee’s delicate art balanced and filled out nicely by longtime color partner Jane Chung’s work. Really, it looks so good that it almost gives Ozymandias reason to exist.

Almost.

For all the problems with Wein’s writing in the series — beyond the fact that it is, essentially, just a glorified recap of the original series from the point of view of one character, there’s also the fact that Wein’s dialogue simply sounds too unlike Moore’s to ring true, as well as Wein’s apparent desire to explain everything from the original series, including at one point, a sequence explaining that “Nostalgia,” the fragrance from Watchmen, is so-called because it reminds him of an former love — there are two decisions made in the writing that feel particularly demonstrative of Wein’s apparent desire to address what he presumably saw as problems with the original work.

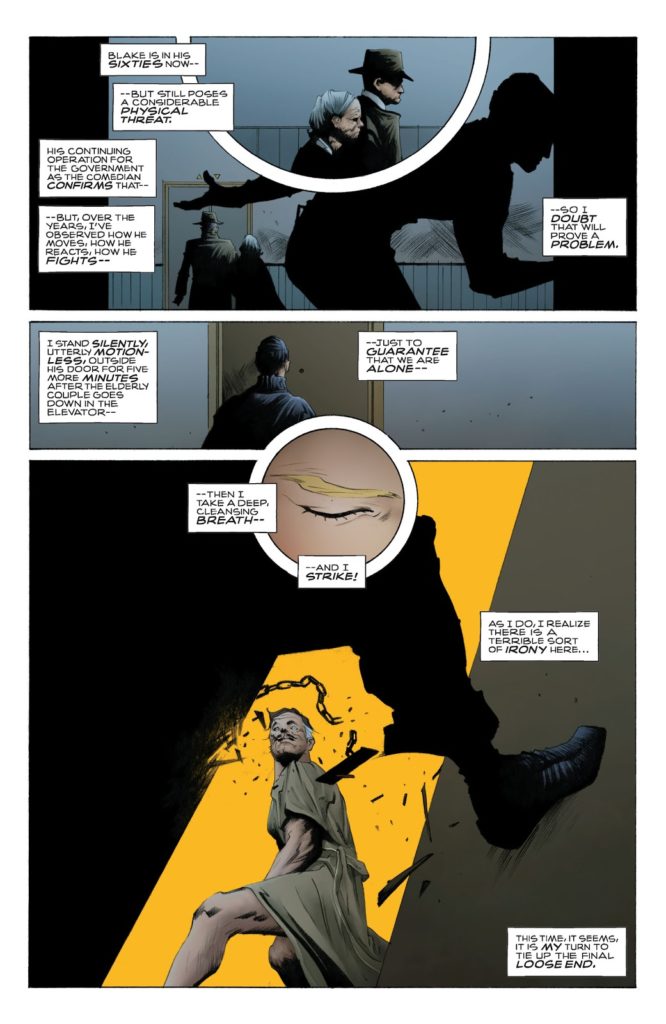

Firstly, the revelation that Veidt had bugged Moloch’s apartment, allowing him to overhear the Comedian’s confession — with narration explaining that “Jacobi himself would come to me the following morning to report all that had transpired” — in an attempt to paper over the possibility that perhaps the all-seeing, all-knowing Ozymandias had overlooked something… and, more obviously and, depending on your point of view, egregiously, placing the fact that Alan Moore stole the climax of Watchmen from an episode of The Outer Limits into canon, as Veidt himself does the same thing. “I was re-watching the entire run of a relatively short-lived TV series called The Outer Limits when I finally found it,” he explains midway through the series, after searching through sci-fi novels and movies in the hope to find a concept so inhuman as to save the world.

Firstly, the revelation that Veidt had bugged Moloch’s apartment, allowing him to overhear the Comedian’s confession — with narration explaining that “Jacobi himself would come to me the following morning to report all that had transpired” — in an attempt to paper over the possibility that perhaps the all-seeing, all-knowing Ozymandias had overlooked something… and, more obviously and, depending on your point of view, egregiously, placing the fact that Alan Moore stole the climax of Watchmen from an episode of The Outer Limits into canon, as Veidt himself does the same thing. “I was re-watching the entire run of a relatively short-lived TV series called The Outer Limits when I finally found it,” he explains midway through the series, after searching through sci-fi novels and movies in the hope to find a concept so inhuman as to save the world.

It’s cheeky, so much so I almost appreciate it, but it still does what the rest of the series spends so much time doing: Explaining and retelling things that no-one but fans of the original book would really care about, and doing so in such a way as to fail to illuminate anything to those same fans. Who is Ozymandias for, then? Jae Lee fans, I guess. And, perhaps, Len Wein’s need to “fix” Alan Moore’s writing one last time.

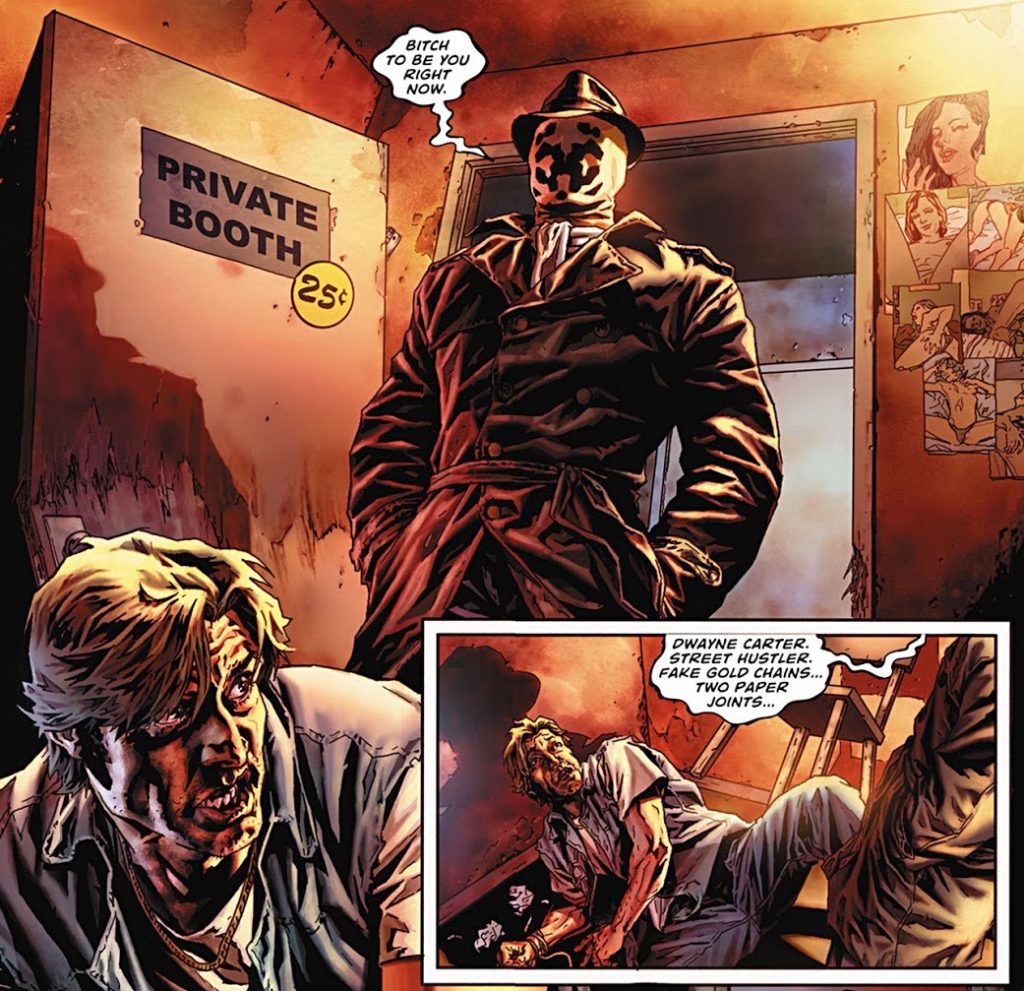

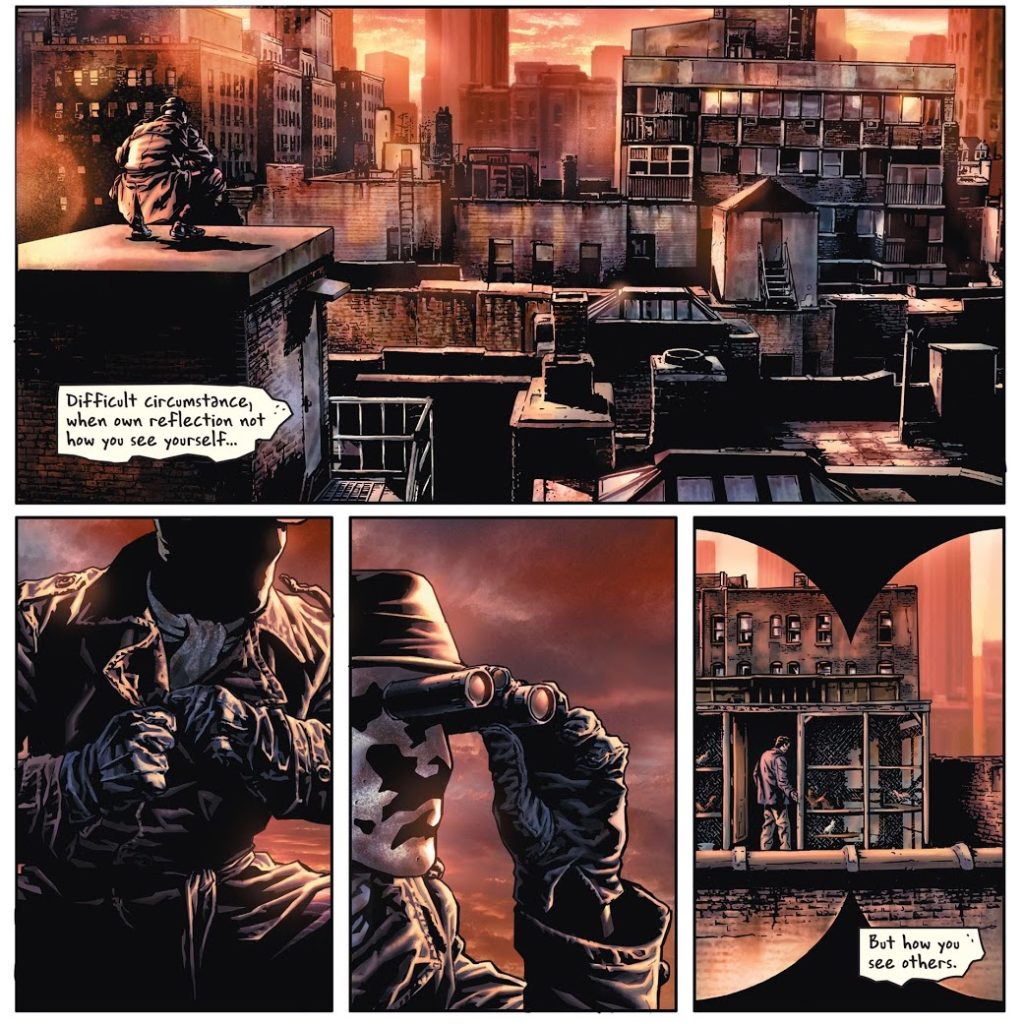

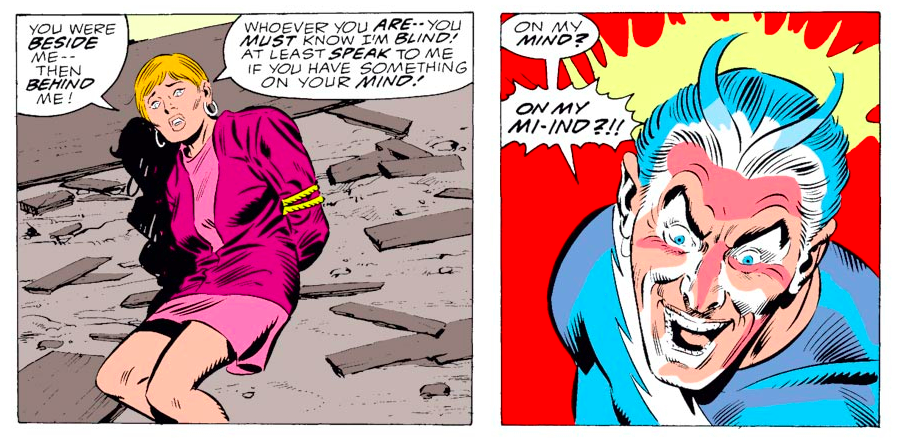

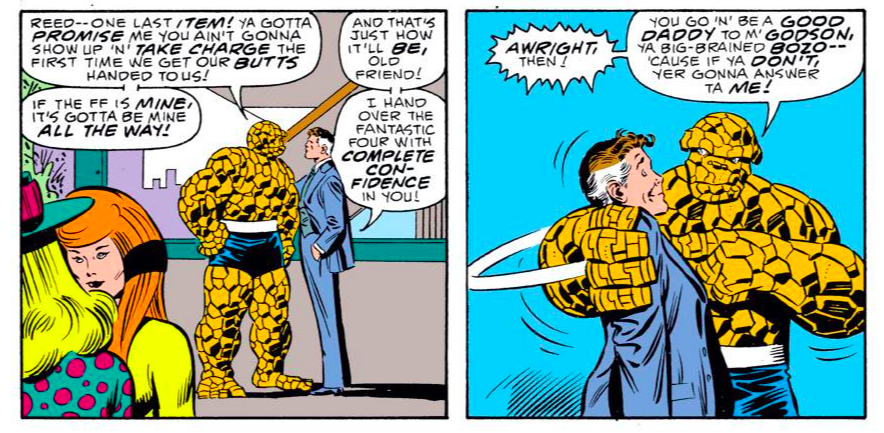

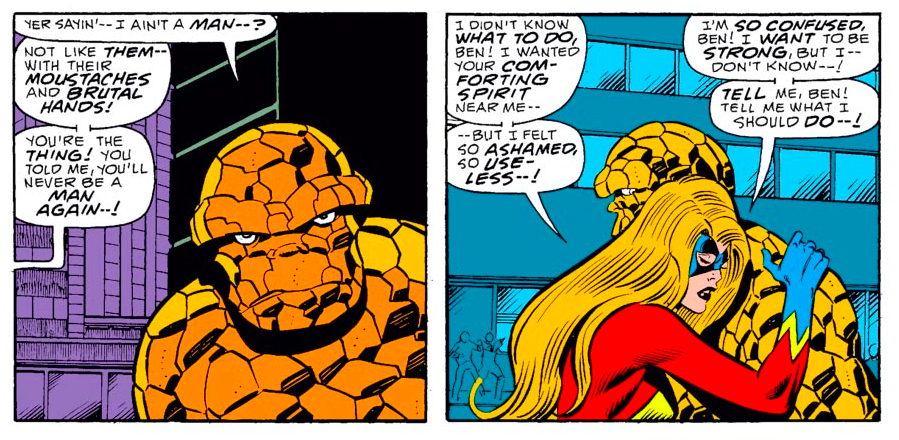

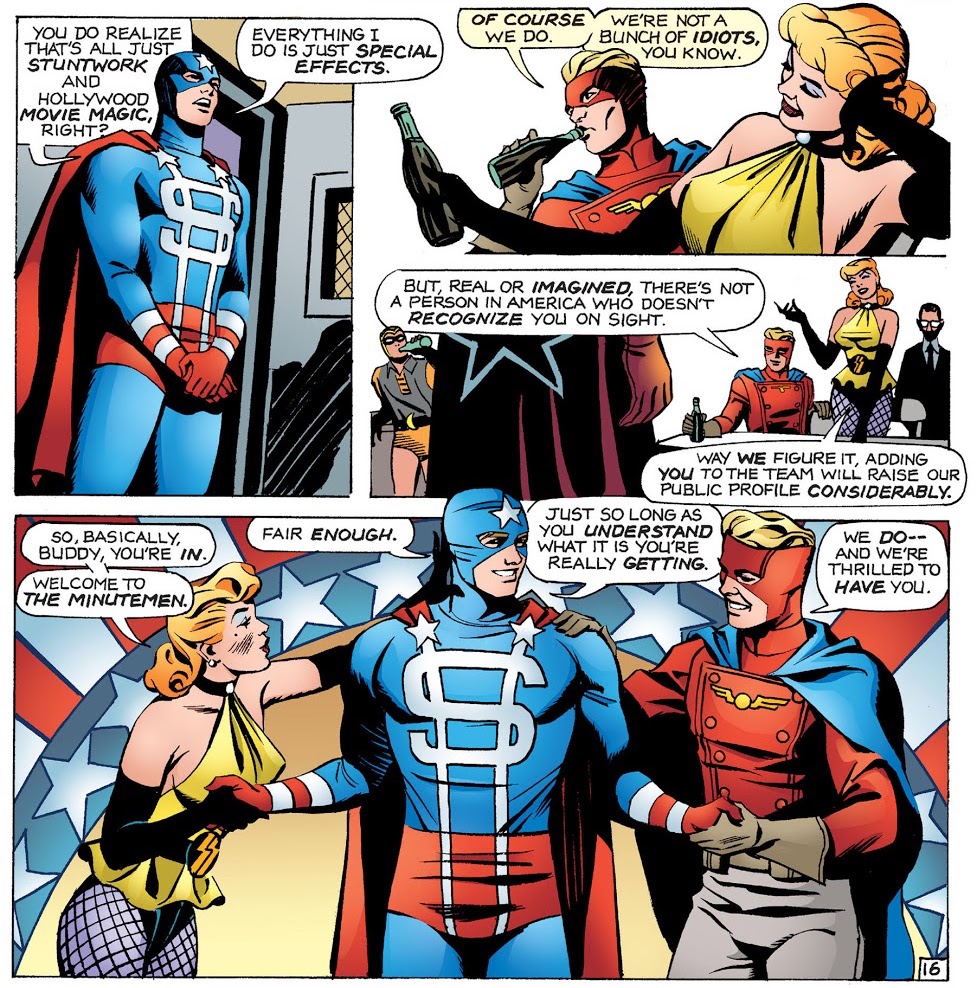

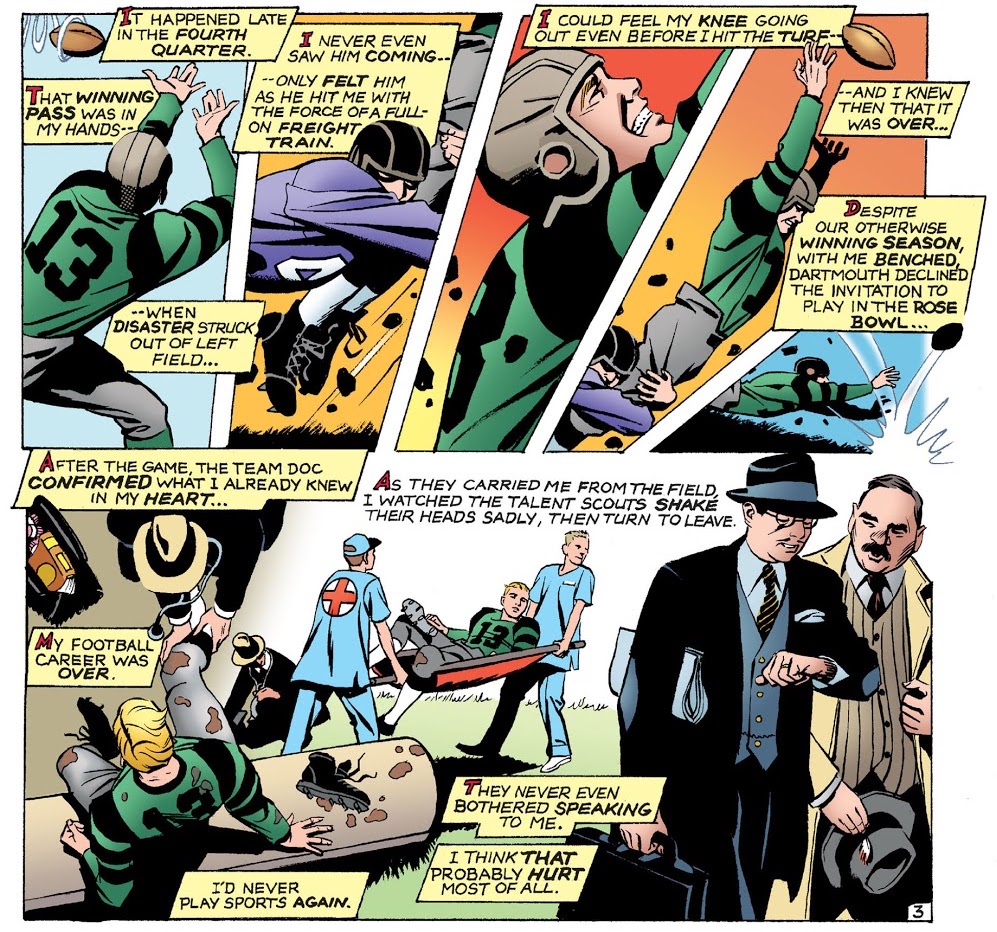

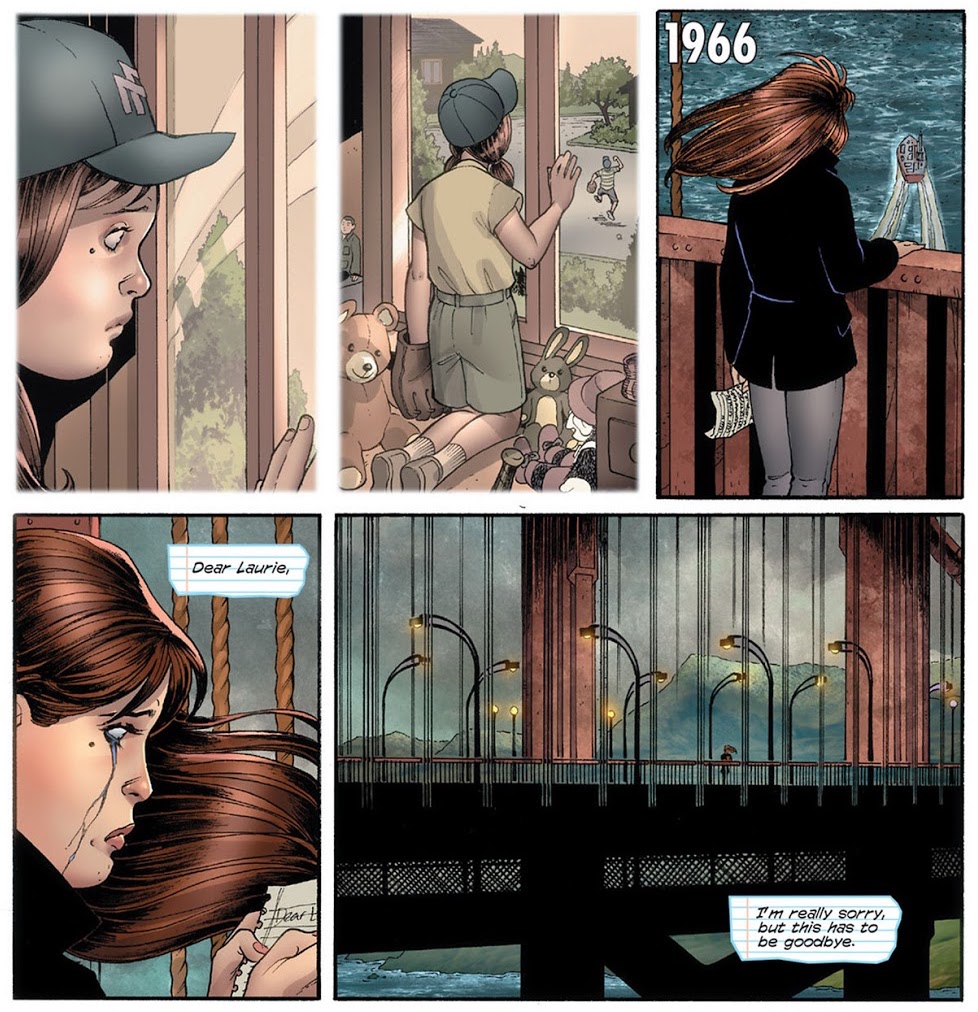

Moloch is more straightforward; Straczynski gives him the Mole Man’s origin, more or less — an ugly child made uglier thanks to a cruel world — with what is essentially a slight, unoriginal story given life by Eduardo Risso’s loose, fun cartooning. Probably the most interesting thing about the series is its format, with the first issue given over to Jacobi’s past all the way up to incarceration, and the second entirely to his post-release relationship with Adrian Veidt. That relationship, of course, was abusive and manipulative in ways that seem almost comedic in scale and intent — it’s not enough to use Jacobi as a pawn, Veidt also has to give him cancer, as well — but Straczynski at least attempts to mine this for some emotional resonance, as opposed to Wein’s sterile, “logical” retelling of the Ozymandias series.

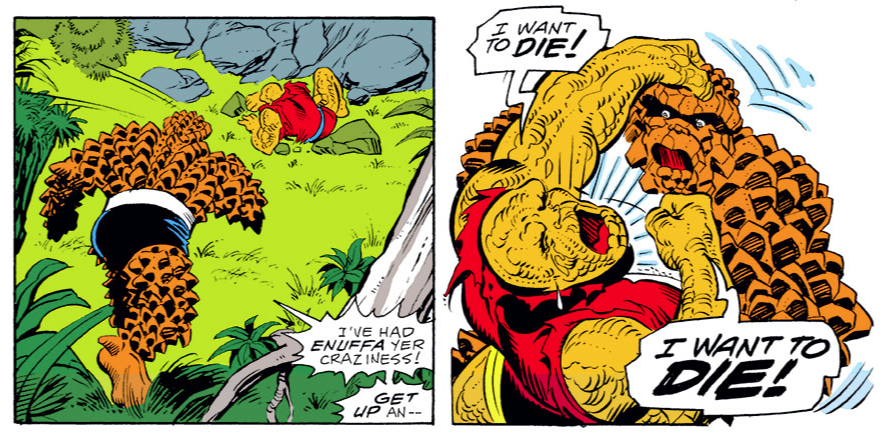

I wrote “attempts,” for obvious reasons; not only is Straczynski not the most capable writer when it comes to mining emotional resonance in his work, but the situation is so cartoonish — especially as portrayed on the page — that it’s impossible to find it anything other then ridiculous and melodramatic… something that Risso plays up even more in his artwork. While Risso’s broadness works for the first issue, especially with the kid Jacobi, it’s less successful in the second issue, at odds with the subtlety Straczynski is clearly trying to push (unsuccessfully) into the story. It’s a shame, because the book still looks good, even as it fights with itself tonally.

Of the two titles, Moloch is almost certainly the more successful, despite that lovely Jae Lee artwork in Ozymandias; it’s less literal, kinder to and more willing to actually engage and explore the origins book as opposed to reiterate and explain it, and, best of all, significantly shorter. Neither series really adds anything to Watchmen or the fictional world is exists in, and in that case, shouldn’t we be grateful for small mercies like a shorter length more than anything else…?

Recent Comments