I was kind of wondering when this might happen.

When we put together the Patreon and the plans to write weekly posts, in the back of mind, I kept wondering what would happen on the week where I just didn’t feel like I had anything to say. I’d even started brainstorming perennials I could write ahead of time and just plunk in here when the need demanded it. (Bob Haney’s The Brave and the Bold! The Howard the Duck omnibus! ABC Warriors!) As much as I’d like to be like Graeme, who has the focus to pop out 800-1200 words in a tidy stream, straighten them up, and get them out the door, it’s a messier thing for me. It’s gotten a little harder to stay focused, to make sure the words mean what I want them to, that I’m on the right track. Youth is great for making fanatics–it can be easier to be single-minded when you’re young, or at least it was easier for me.

In fact, just seven hours ago, I was floating in a sensory deprivation tank, something I’ve done a handful of times now, and my mind just would not stay still. Even the stuff I was being obsessive about kept getting displaced by the waterwheel of my mind. It’s one of those times where I’m tremendously grateful for the Internet because it’s become my one-stop shop for excuses about my brain. Can’t concentrate? INTERNET. Lingering on things that make me angry? INTERNET. Sex stuff, in one second loops? Well, that really is the Internet, thank goodness–I hope someone somewhere has put together a theory about how a .gif mimics obsessive thinking, and whether cycling through a ton of gifs might exacerbate or lessen obsessive thinking. (For me, I think it tends to exacerbate it.)

Obsessive thinking, obsessive habits. I’d actually thought for most of my life that I was far too lazy for either, but, um, then I realized I had twenty-seven longboxes of comics. So…

Anyway. Part of the problem with my obsessive patterns is I can go through periods of reading a shitton of comics, and then a period where I just…don’t. I mean, there’s always going to be a thing or two, a book, a bit. But I notice right now I’m in a pattern of seemingly constant comics accumulation, but my comic reading seems to wax and wane depending on whether it’s a podcast week or not. And when it’s not, there are times where I just look at a big ol’ pile of comics, and even the dumb, colorful ones feel like…homework. And yet that will not stop me from continuing to buy them. (Man, between the Transformers and the Dynamite Humble Bundle sales, and the Batman 750, the Suicide Squad, and those forty-five cent SDCC graphic novels, it’s like I took a shotgun to my digital purchasing budget.)

All of which is to say: here’s kind of the edges of the peanut butter jar, the stuff I’ve either managed to pick up just today or recently and wade through. Here are the thoughts-without-thinking:

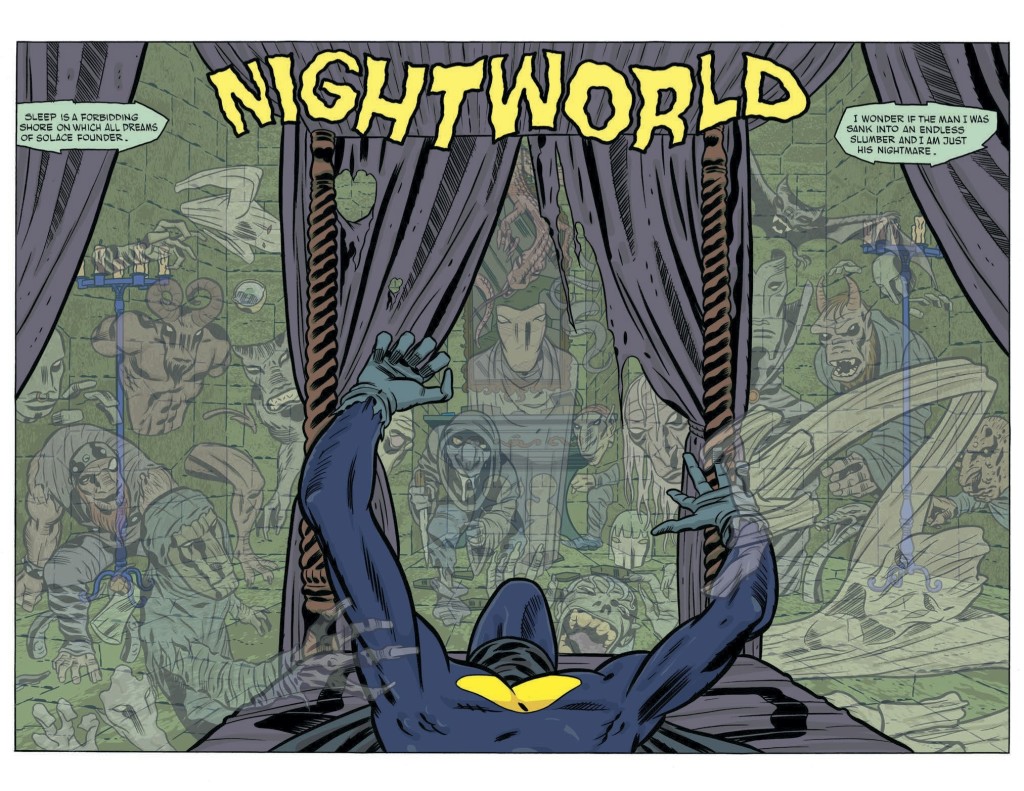

Sandman: Overture #3: I was actually shocked when this hit the stands this week. Like, this odd shock of “oh, that’s not over yet?” It hasn’t been high on my list of priorities. But this was easily my favorite issue yet, if not probably one of my favorite things from Gaiman (admittedly a pretty short list, and although I haven’t given it any thought it is probably, in rough order: that Riddler story; the Emperor Norton issue; his deposition testimony in his case against Todd McFarlane; the nurse’s hands making the bat signal as baby Bruce Wayne shoots out of his mom’s vagina; Coraline; his description of Amanda Palmer looking perpetually surprised in the morning before she’s applied her eyebrows; and then this?) For the first couple of pages, I thought “well, okay, a lot more nothing is going to happen but it’s the best looking nothing yet,” and then…stuff happened? I mean, it’s Neil Gaiman so of course, by “stuff,” I mean, “a dramatic confrontation is defused in a non-violent but flashy manner, and someone tells somebody else a story,” but, I dunno, those things worked? It probably helps that the former was made easier by a certain amount of Moffat-written Dr. Who, and the latter was told pretty economically, considering how much more blowsy other comic artists can get. Or maybe I just really like the way J.H. Williams III draws that cat? Anyway, yeah. I’ll be excited in 2017 (or whenever) when the next issue comes out.

Snipe: Picked this up when Rich said some nice stuff about it over at Bleeding Cool. Read it twice. Once when I picked it up, once just now. A digital only comic (I think), another collaboration between writer Kathryn Immonen and artist Stuart Immonen, it is actually two different comics, Snipe 01 and Snipe 02: the first being a piece about a photographer in the woods where the graphic narrative is relatively straightforward (though elusive) and the narration is elliptical, almost stream-of-conscious; and the second where the narration is a relatively straightforward recounting (though, again, almost stream-of-conscious) of the career of Simo Häyhä, a Finnish sniper who had 505 confirmed kills during the Winter War, and the graphic narrative is a yet another running stream-of-consciousness commentary on the narration.

First impression: Jesus Christ, the Immonens must have access to tremendously good pot.

Second impression: Jesus Christ, the Immonens must have access to tremendously good pot, and they’re both tremendously talented. I always appreciate the distinctiveness of Kathryn Immonen’s narrative voice, even though it’s never really Madras’d my lentils–there’s a distance to the narrative voice that never quite jibes with the whimsy–but it comes much closer to working here for me: it’s an omniscient narration of a distant, somewhat alien omniscience. And Stuart Immonen’s work is just breathtaking in Snipe 02, sliding up and down one end of that pyramid Scott McCloud outlined in Understanding Comics from photorealism to iconography as the narration similarly swings from the specific-but-general (the heights of various types of men, the types of various colored deaths in history and literature) to the specific-but-vague (there are two possible dates on which Häyhä may have been shot).

I’m tempted to say Snipe 01 is about how the circularity of thought is joined to the circle of life, and Snipe 02 is about how the trajectory of….history?…is tied to the trajectory of life-toward-death? Maybe? Although that’s probably me just flailing about and grabbing some of the good stuff from Steven Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion? It’s not nearly so cut and dry, but it is tremendously compelling. I liked it, although more than anything it made me wish I could get my hands on more Golgo 13 comics. Because I’m pretty much a simpleton.

The Six Million Dollar Man: Season Six #1-3: Keep thinking I got these in the Dynamite Humble Bundle but nope, they were part of a Comixology sale? Because of my age, I’m of course halfway in the tank for this sort of thing, the Six Million Dollar Man being among the better of the bad hands us nerds were dealt back in the ’70s, TV-wise. And I dig the idea of doing a “season six” that would bring in all the best stuff from the series and kind of pretend that this what the show might’ve turned out to be.

It’s a rigged game, of course, because back in the ’70s, Congress passed a law that dramatic TV shows could only use a single type of subplot to connect episodes, and that was the Fugitive subplot. Because the subplot of SMDM: S6 is *not* “Steve Austin is on the run, accused of a crime he did not commit,” a more stringent nerd than I would call shenanigans.

Honestly, half the fun of these three issues is, bless them, the script pages in the back of these “digital editions” where writer Jim Kuhoric tries to convey to his artist just how insanely different the 1970s were from now (“We see [Oscar Goldman] from behind as he sits at his large oak desk and is talking on an old-fashioned corded telephone. There are no computers on his desk–this is before the personal computer.”) and then seeing the flubs that are made anyway. (In issue #1, Steve talks about going with Oscar to a popular new sushi restaurant, which is theoretically possible since I guess Sushiko opened there in 1976 but even experienced world travelers like Goldman and Austin wouldn’t have talked about it as “there’s this new little sushi place in Georgetown.”) (Also, it’s impossible to properly convey how hilariously bummed I was when they have Maskatron be controlled by joystick but it’s totally not an Atari 2600 joystick but one of those later P.C. style faux-jet joystick things. I actually laughed aloud at my own disappointment.)

Anyway, in issue #1 Steve Austin fights sharks. In issue #2, Alex Ross draws a cover that is totally based on a a piece of art I recognize (though I can’t find it now, damn my eyes? I want to say it was one of the covers of the Six Million Dollar Man magazine or comic?) and Maskatron fucks shit up. And in issue #3, Steve Austin fights a Metal Gear. With better interior art, I probably would’ve been more into this. Between laughing at myself, imagining the disappointment Jim Kuhoric feels when he sees how his scripted pages are ending up, and trying to imagine what someone unfamiliar with the show is going to think of the onomatopoeia for the bionic sound effects (“Bana Nana” is the one that I think would really baffle them–and, really, editors, you couldn’t come up with a standardized “bionic” font for the sound effects that might clue people in as to what’s going on?), I admit to being entertained. God help me, I might actually buy more of these if they go up on sale for $0.99. I don’t have faith in anyone else involved, but I think it’s a fair bet Kuhoric is going to give us Bionic Bigfoot and another variation on the Venus Probe and hopefully like the sharks he’ll throw in some other stuff that was hitting the scene in the late ’70s (bionic punk rockers? bionic disco dancers? bionic body snatchers?), and I’m very much looking forward to seeing Alex Ross draw, I dunno, the Six Million Dollar Man gameboard.

But can I recommend these to anyone else who is not as messed up as me? No sir, I cannot.

Recent Comments